Louvre Mirror

Just juxtaposing these two images for future reference.

adventures in my head

Is on my mind after the Etruscan Workshop last Friday.

There babies’ inspired a twitter thread on cross cultural comparisons and upright positioning as I couldn’t get it out of my head. Still having trouble letting go thinking of them, hence this blog post. The most interesting difference between these bronzes and the clay examples previously known is how much more detailed ornamentation these have. That’s a fibula on the far left exposed figure (not as I first thought an apotropaic phallus!). I’d always thought of fibula as adult dress adornment! So interesting to shift that mental image of the possible functions of such a common artifact.

If you’re not familiar with swaddled babies as votives (more familiarly in terracotta), check out this great blogpost from the votives project.

I also learned in the workshop that we have ancient swaddling directions from Soranus:

Use a manger as a bed!!! Isn’t that fun.

Stumbled over an article and couldn’t resist reading:

Rose, Charles Brian. “Forging Identity in the Roman Republic: Trojan Ancestry and Veristic Portraiture.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 7 (2008): 97–131.

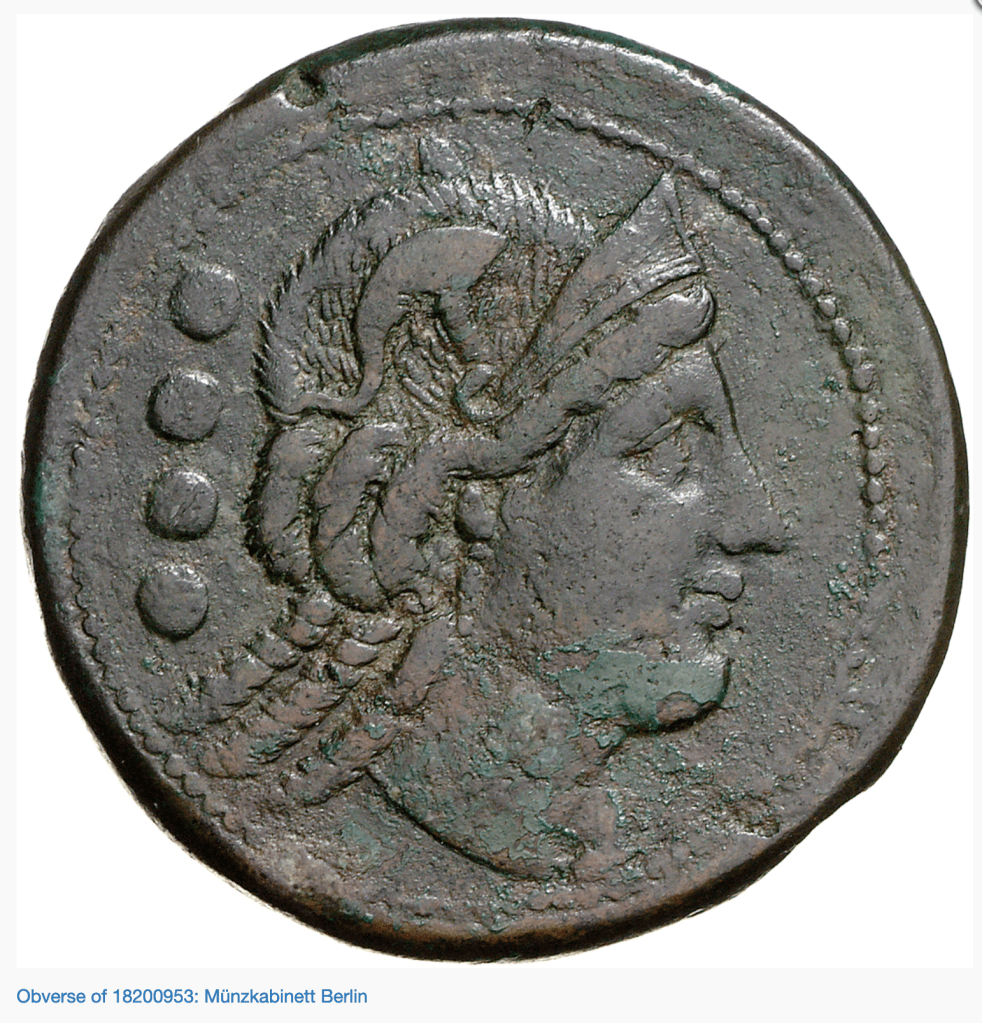

Here starts from the coins of which I approve but I’m not so sure he makes the most of them a less informed reader my think Fig. 1 dates to the Pyrrhic War!

The first Phyrgian helmet on the Roman series is RRC 19/2. RRC 14, 18, 19 are all of the same time period, probably just before the first Punic War, so early 260s, maybe 270. I have a hard time connecting it to the Pyrrhic war, but do agree it invokes a Trojan ancestry (Yarrow 2021: 93). I’d also quibble and say a helmet and a cap is not necessarily the same thing, esp. in iconographic terms.

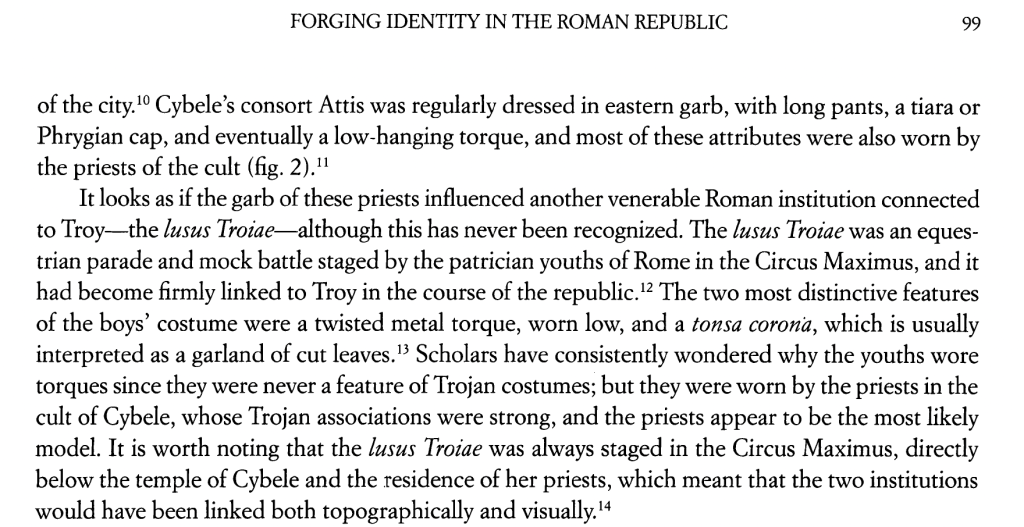

Rose goes on to make a comparison between the garb of the priests of Cybele and the costumes used in the lusus Troiae. His views observations especially on the torque and the relationship of the circus Maximus to the temple are very smart indeed.

My only quibble is that these games seems to have been a ‘restitution’ (i.e. invention) by Julius Caesar and not an authentic republican tradition. These are things be cannot be sure of but their importance in dynasty formation is well attested, cf.

Menichetti, Mauro. “« Troiae lusus »: mettere in scena le origini di Roma.” La Parola del Passato 74, no. 2 (2019): 287-299. [ILL requested]

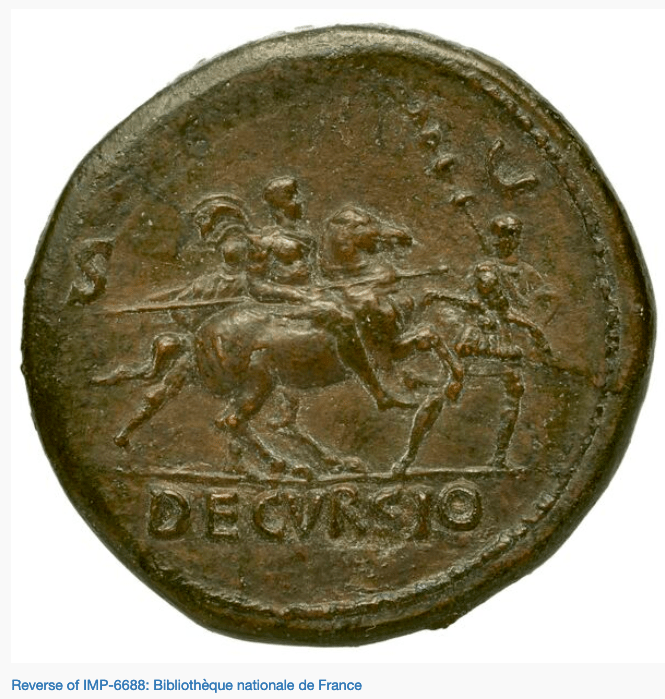

For the numismatically inclined

SMITH, DEREK R. “The DECVRSIO Sestertius Types of Nero and the Lusus Troiae.” The Numismatic Chronicle (1966-) 160 (2000): 282–89. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42668274.

has proposed a connection between these bronze coin images of Nero and the Troy games, while also moving away from the idea that they are depicted on the base of Antoninus Pius in the Vatican. (I tweeted a different version of this coin and it created a stir about apparent stirrups). None of these costumes are reminiscent of the cult of Cybele, but then again the identification is tentative…

I just have to straight up disagree with this based on the reception of Battakes in 102 BCE as reported by Diodorus. On this I like Bowden’s chapter, but there are new pubs now. The next bit though is right to emphasis the importance of the under utilized

—some how I lost a great deal of my content that came after this point in the post and auto saves only restored to this point, I can’t quite be bothered to write it all out again but as I did upload the images here they are as a slide show —

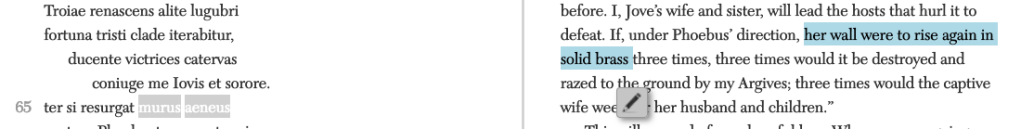

Jeremiah 1:18

Jeremiah 15:20

Horace Epistle 1.60

Horace Carminae 3.65

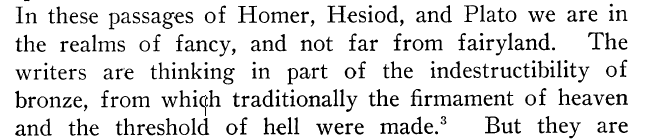

I was really digging into try to think about what these parallells meant but lucky for me this dude already did!

WORMELL, D. E. W. “WALLS OF BRASS IN LITERATURE.” Hermathena, no. 58 (1941): 116–20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23037709.

He has a great little joke on the first page:

“…assuming that a bronze tower need no more be of bronze than an ivory tower need be of ivory…”

I agree with this fairy land view. He goes on after this to make the case that bronze had magical properties, of this I am less convinced is relevant in these literary examples… He also speculates that in Horace’s Epistle the bronze walls are the goal or home base of the game and connects it to a childish version of the lusus Troiae! I’m not convinced but points for creative thinking!

He then jumps the shark and goes in for early English lit reference, claiming Horace lies behind this imagery.

NO MENTION OF JEREMIAH!!! Wormell must have fallen asleep in Sunday School.

Homer (maybe Hesiod) are likely in dialogue with Eastern traditions on which Jeremiah is also drawing (I’m thinking of the East Face of Helicon and West’s thoughts on connecting Sappho to Babylonia magic and Psalms; no, I’m not going to go find a citation right now, it is in my teaching notes if I ever need it). Plato is drawing on Homer. Horace is likely also drawing on Homer in an archaizing fashion. I’d love to connect Horace to Semitic literary traditions just for fun, but I don’t think I can really do that with any intellectual honesty.

Wait….

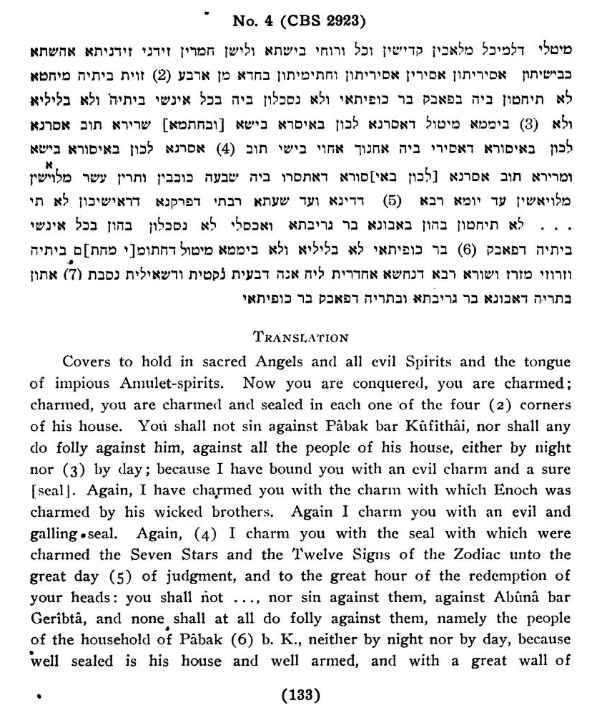

That magic idea of Wormell’s might have some merit:

[arrived from ILL! 5-3-23]

(link to above from which below is taken)

I kept digging and lo! A commentary on the wall of tin in Amos gave be to pharonic Egypt references:

A full view of this commentary is available on the Internet Archive

From Breasted 1906 Ancient Records of Egypt:

update from 5-3-23:

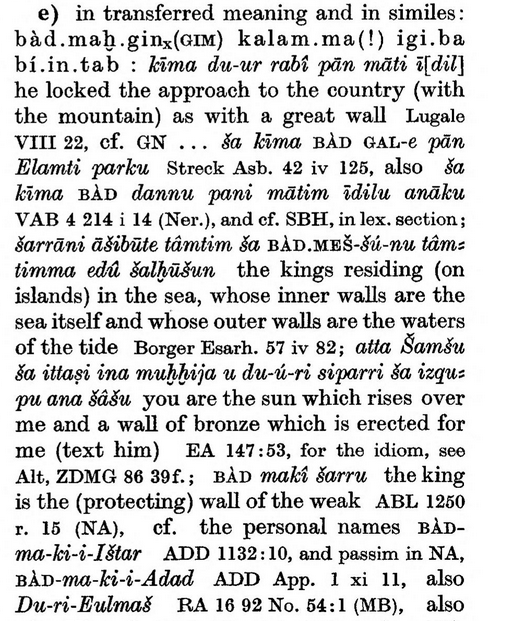

From the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary:

s.v. dūru

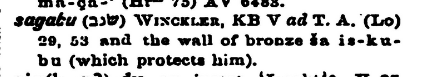

From Muss-Arnolt’s concise Assyrian dictionary:

Here’s our one complete (non-literary?) nenia from antiquity and even this one had to be reassembled across the centuries.

Rex eris, si recte facies

Qui non faciet, non eris!

You will be king, if you act rightly;

He who does not act, will not be!

Reconstructed from Horace Ep. 1.1. 59-63 and Porphyry ad Ep. 1.1.626

I promise it is more catchy in the Latin than I can make the English!

The best discussion is:

Dutsch, Dorota M.. “« Nenia »: gender, genre, and lament in ancient Rome.” In Lament: studies in the ancient Mediterranean and beyond, Edited by Suter, Ann., 258-279. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Pr., 2008.

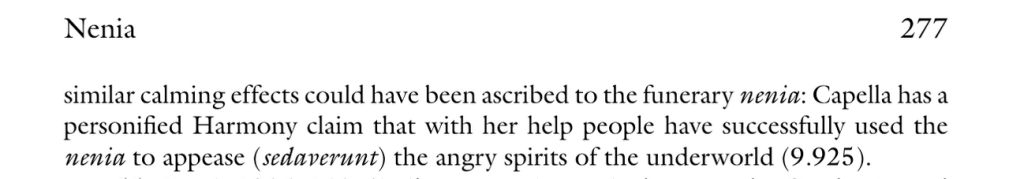

But her concern is on the more common use of term Nenia, i.e. in its funerary context:

| Abstract of her piece: Two discourses were involved in the Roman funeral. One, the official « laudatio funebris », a speech commemorating members of the upper class, was the domain of male relatives of the deceased. The other, a chant called « nenia », was entrusted to female professionals and could thus offer us a rare example of Roman women’s poetic skills, but we have no script of a genuine lament sung at a Roman funeral. Scattered evidence regarding various types of the « nenia » is assembled and examined to recover some of the rules and cultural connotations of this lost genre. |

Why do I care? Well I’m including the little rhyme in my transition between chapter one and two of my current book project. The first chapter “What sort of thing is a king?” investigates literary generalities about the nature of Roman and Foreign Kings and Roman relationships to kings, again in generalities and truisms not specific examples.

(I realize as I type this it is an interesting reprisal of my work on the historiographical uses of Eastern Kings in my first book (2006), esp. in Chapter 6, p. 291 ff: I best go read myself and try to see why I can’t get these questions out of my brain).

The second chapter addresses memories of Numa in the pre Augustan, esp. pre Ciceronian corpus. The little ditty I call in to try to access a bit of popular culture on the connect of (morally) right action and kingship in the Roman mind to set up the reader (who may have skipped chapter one!) to better understand the context in which the Numa traditions were formed. The writing challenge is to decide what of the Numa tradition goes in the chapter two and what is distinctive enough to be saved for chapter three on the Ludi Apollinares and their meaning.

I’m particularly interested in how recte and rex are linguistically connected through the verb rego, rexi, rectus.

Which in turn led me to Livy 6.6 AND Chris Kraus’ fabulously spoton commentary

Chiasmus is that A:B::B:A pattern in nenia

For reasons that aren’t public yet I think my sabbatical will be cut short. Not all bad reasons and largely of my own agency; I’m shifting my professional priorities it feels. More anon, sorry to be vague but the count down has started to feel weird. I do have 119 more days in which I can primarily focus on writing but I will likely also be taking on an preparing for other work. Regardless, I want this book out soon, even if I have to borrow time here and there. I do like blogging so I will try share bits as they come up.

I’ll add more here when I spot them. I like this type of thing for thinking about coin imagery like the ketos helmet/headdress on the coins of Vetulonia (blog post) or even the boar headdress on Roman Republican bronzes. (RRC 39/2 etc…)

Update 5-3-23:

Reading this piece:

Elliott, John. “The Etruscan wolfman in myth and ritual.” Etruscan Studies 2 (1995): 17-33. (link)

Abstract: A large bronze animal’s head in Cambridge (Mass.), Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums Acc. no. 1964.128, is indeed the head of a wolf and was used as part of a masked ritual in which the Etruscans defeated a monster personifying death. Urns, wall-paintings and pottery decoration all provide additional evidence for the connection between wolves and the deities of the underworld in Etruria.

It has great images and I think even without the helmet or the Capitoline Wolf (proven to be not ancient) the corpus of images adds up to a distinctive and important cultural practice. The helmet while likely ancient has been distorted through heavy ‘restoration’ esp the teeth and perhaps low jaw:

So it is evidence of an animal helmet but we cannot say what kind… This object needs some provenience research.

When I saw the basic form of Vatican specimen, it felt very familiar, but I thought I remembered posting about it with one in the MET and another in the Getty, but I think the latter must be false memory as it does not show up on their website. Perhaps I was remember an illustration of the Vatican one from some earlier MET publication… The MET acquired theirs in 1960, I wonder when and how it left Italy. They don’t have any provenance info on the website. Setting the two side by side makes me think intensely of how restoration effects our impression of objects. How different is the impression made by this old MET photo of theirs pre restoration

My favor part of the Vatican one is Hercle (Greek: Herakles) and his patron goddess, Menrva (Greek: Athena).

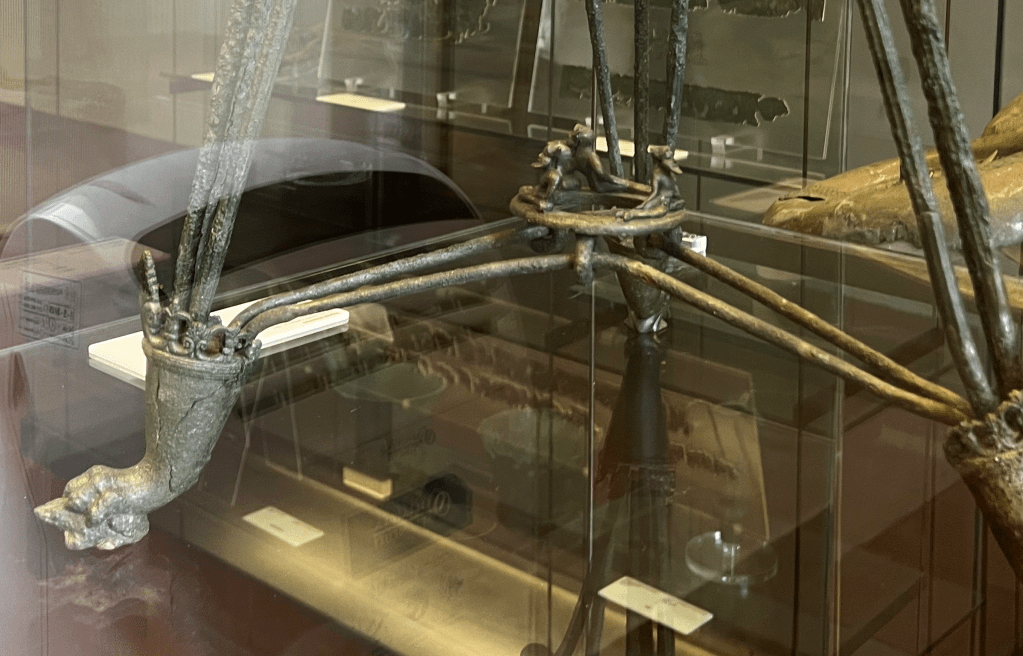

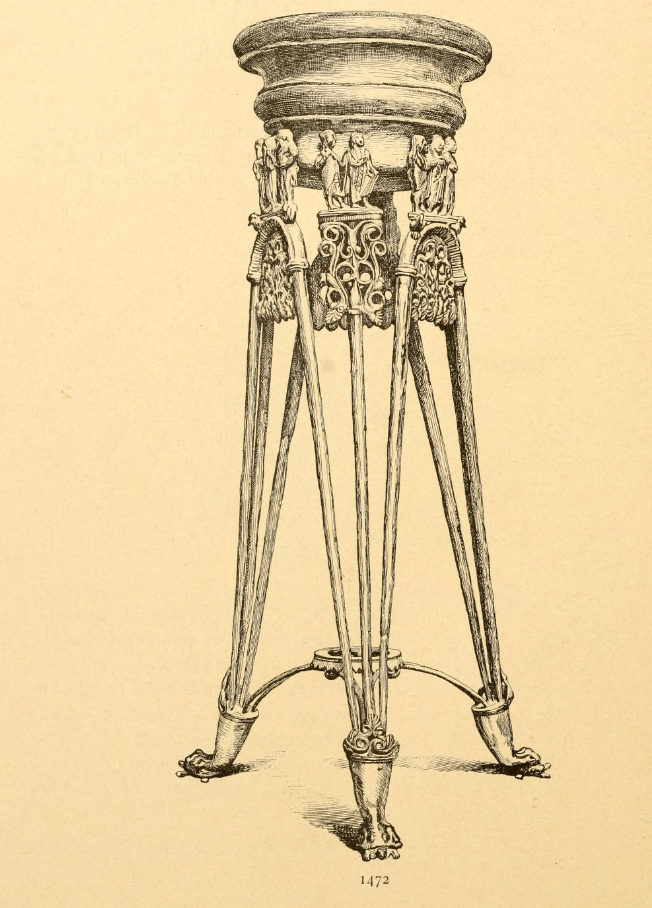

The details of the banqueters on the bottom ring and the paw feet are pretty good too but my photo is terrible. I like the animal feet because they remind me of the paws on RRC 10/1 (earlier post).

Update 5-3-23:

Update 1-22-24:

Said to be found in 1831 in Vulci, now in BnF

Another Etruscan bronze from the Vatican, but I’m posting this one because of how it parallels faces joined together on ancient intaglios. This next image is the same vessel seen from the top. The beard of the mask is the back of that bouffant hair style.

Here some pretty drawings of intagios of the type I mean. I feel there must be a name for this type of image, but I don’t know it.

I saw the above detail from an Etruscan bronze in the Vatican some days ago and I know it reminded me of a coin and one specifically from Italy I’d seen in the ANS some years ago, but that coin doesn’t seem to have an on line image. Iris helped me find the type.

These facing Heracles on the coins of Populonia are unbearded. Memory is fallible.

My brain is very full, my feet tired, and my data storage on my phone threatening to burst. Sometimes one must stop and think and try to integrate everything. So here I am with a negroni just a bit up the via Flaminia at a cafe devoid of other tourists, looking through my snapshots and trying to think about why each thing caught my eye and how not to forget those I care to remember. I started a photo round-up post but that took took long. Instead I think I will give each idea its own post as it seems appropriate.

Yesterday Julian Oliver and Thomas Faucher gave a fantastic discussion on the likely recalling of bronze coins, their melting down and re-issuing in Ptolemaic Egypt. One such in the mid 150s and and other in the 50s BCE. On their slides were two lovely coins of series 6 and 7 which had a female head with distinctive ringlets, Isis is the typical identification but I’m not sure we can say for sure. I often say such ringlets evoke Africa for the Romans and while I can point to Roman examples. I like this iconography for how it shows pre existing Ptolemaic usage of the imagery.