Just didn’t want to lose the reference to this article

I do like an apex (earlier posts) and I’ve argued that the Minucius coins show a pontifex maximus who is chiefly identified by a knife and patera (no apex) (article).

adventures in my head

Just didn’t want to lose the reference to this article

I do like an apex (earlier posts) and I’ve argued that the Minucius coins show a pontifex maximus who is chiefly identified by a knife and patera (no apex) (article).

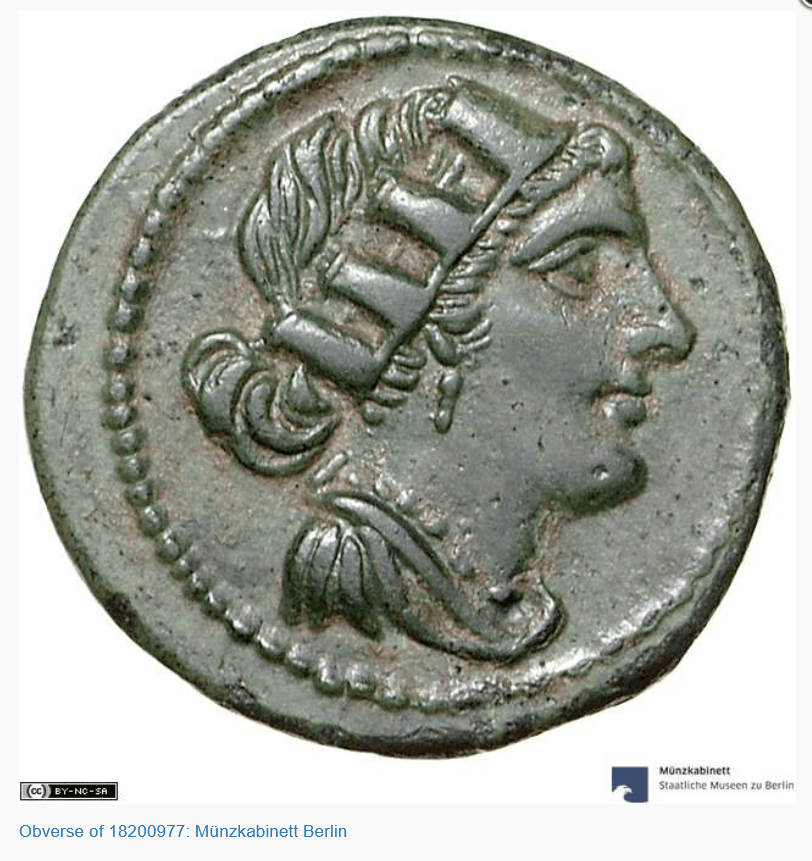

I was recently corresponding with an Italian colleague about the obverse head on the coins of Vetulonia and how to source a decent image.

These are drawings from Sambon:

He’d found this throw away earlier post of mine and that’s how we got talking. Here’s a Paris specimen; a BM specimen.

Well today I was looking for a reference and came across another v old blog post of mine. And lo! Do you see the parallel?

I feel very confident that this intaglio depicts Nethuns wearing a ketos (sea serpent) headdress.

Update 8/24/22:

Update 7-27-23:

Berlin 1888 catalogue:

Update 2/1/24:

A revival/restored type based on RRC 544/19

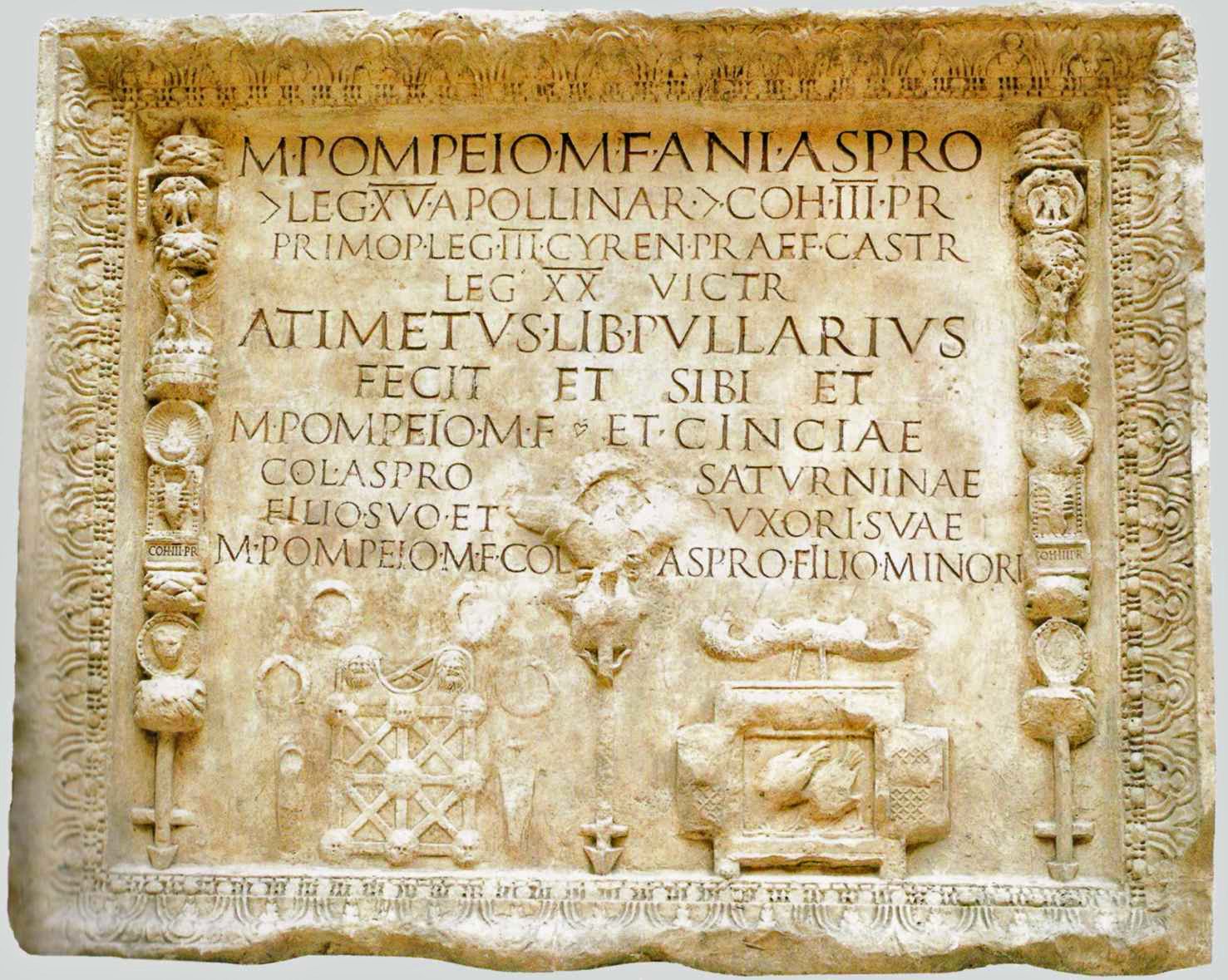

I was looking at depictions of legionary standards and this came back in my search results. I love the way one part of the coin series talks to another….

There is no real suggestion that the controlmarks of the obverse and reverse dies are paired logically for the L. Calpurnius Piso series. So for instance the obverse shown above was paired in an earlier die state with the other BM Specimen illustrated below. And yet, that double axe and that knife look a great deal like this funerary relief created a couple of hundred years later on the other side of the Mediterranean.

Feronia appears on eight coins types struck at Rome by IIIvirs after 19 BCE and before 4 CE during the short lived republican coin type revival of moneyers signing coins. These coins also commonly revive early types on which I’ve blogged before. (Hercules example, Sicily example)

So I was looking at this coin and a bell went off in my head.

These representations of Feronia (identifed with FE or FER or FERO as a legend), remind me strongly of RRC 39/5, a type with a mysterious obverse (early blog post). I strongly suspect that Turpilianus’ Feronia is modeled on this early coin type. That doesn’t mean that the earlier coin type was intended to represent Feronia but that has to be considered. A Roman at the end of the first century BCE has a much richer visual knowledge base to use to identify historical iconography, not to mention a basic cultural framework.

Livy 26.11 (cf. Sil. Ital. Pun. 13.83ff.) recounts that Hannibal sacked the wealthy sanctuary of Feronia. At about the same time this coin was struck.

The city of Feronia is at the foot of Mount Soracte, with the same name as a certain native goddess, a goddess greatly honoured by the surrounding peoples; her sacred precinct is in the place; and it has remarkable ceremonies, for those who are possessed by this goddess walk with bare feet through a great heap of embers and ashes without suffering and a multitude of people come together at the same time, for the sake not only of attending the festal assembly, which is held here every year, but also of seeing the aforesaid sight.

Strabo 5.2.9

There is also another account given of the Sabines in the native histories, to the effect that a colony of Lacedaemonians settled among them at the time when Lycurgus, being guardian to his nephew Eunomus, gave his laws to Sparta. For the story goes that some of the Spartans, disliking the severity of his laws and separating from the rest, quitted the city entirely, and after being borne through a vast stretch of sea, made a vow to the gods to settle in the first land they should reach; for a longing came upon them for any land whatsoever. At last they made that part of Italy which lies near the Pomentine plains and they called the place where they first landed Foronia, in memory of their being borne through the sea, and built a temple owing to the goddess Foronia, to whom they had addressed their vows; this goddess, by the alteration of one letter, they now call Feronia. And some of them, setting out from thence, settled among the Sabines. It is for this reason, they say, that many of the habits of the Sabines are Spartan, particularly their fondness for war and their frugality and a severity in all the actions of their lives. But this is enough about the Sabine race.

Dionysius RA 2.49.4-5

After this war another arose against the Romans on the part of the Sabine nation, the beginning and occasion of which was this. There is a sanctuary, honoured in common by the Sabines and the Latins, that is held in the greatest reverence and is dedicated to a goddess named Feronia; some of those who translate the name into Greek call her Anthophoros or “Flower Bearer,” others Philostephanos or “Lover of Garlands,” and still others Persephonê. To this sanctuary people used to resort from the neighbouring cities on the appointed days of festival, many of them performing vows and offering sacrifice to the goddess and many with the purpose of trafficking during the festive gathering as merchants, artisans and husbandmen; and here were held fairs more celebrated than in any other places in Italy.

Dionysius RA 3.32.1 (cf. Livy 1.30)

In Italy in the time of the Caesarian war people ceased to build towers between Terracina and the Temple of Feronia, as every tower there was destroyed by lightning.

Pliny NH 2.56

Di Fazio, Massimiliano. “Feronia: the role of an Italic goddess in the process of cultural integration in republican Italy.” In Processes of integration and identity formation in the Roman Republic, Edited by Roselaar, Saskia Tessa. Mnemosyne. Supplements; 342, 337-354. Leiden ; Boston (Mass.): Brill, 2012. Abstract: The cult of Feronia was introduced in Rome from Sabine territory in the 4th or 3rd cent. B.C. Worship of the goddess was then carried throughout Italy, following the routes of Roman expansion. Religious Romanization was sometimes a matter of three levels : there were the Romans, the Romanized, and the locals. There has been an underestimation of the contribution of indigenous cultures to the formation of Roman culture.

Di Fazio, Massimiliano. Feronia: spazi e tempi di una dea dell’Italia centrale antica. Roma: Quasar, 2013.

Lots more earlier bibliography on APh, mostly in Italian.

Update 1-20-23:

I am indebted to Dr. Sánchez for sharing with me this authoritative piece of scholarship. I recommend it to any readers of this blog equally interested in provincial coinage, oath scenes, and/or the transition to empire.

This started as a twitter convo but got interesting and as it is hard to search twitter for past information, I’m going to echo what I learned there here.

MD pointed out this specimen looks tooled and I agree. McCabe wondered whether the tooled specimen is ancient or modern. There was concern also about the shape of the hammer on which ABD commented on twitter. Then MP pointed me towards a photo on an internet discussion forum. All the photos below are from that discussion. The owner of the coin and others engaged in the discussion are said to be in Lyons. The second set of photos seem to be from a seller. In the discussion there was concern A) the specimen might be cast and/or B) the specimen might be plated. It has a reported weight of only 2.7g.

Looking at the BnF specimen and this one I’m suspicious that they may share a casting mould, but I’m not 100% confident.

The text describes the coin as small, bronze and exceedingly rare. The author associates it with know historical events. I cannot find any type that is a good candidate for inspiring this engraving. I ran through auction databases, RPC, OCRE, CRRO, etc… Nothing at all. Did it exist? Was it a fantasy piece? Do you recognize the inspiration?

Funerary Relief of M. Pompeius Asper, Palazzo Massimo, Rome

A nice engraving in the public domain:

This 1562 illustration of RRC 320/1 is lovely. I wanted to add it to a note on an older post on this type just to keep the citation but I cannot find such a post. Odd.