UPDATE 2/4/22: see now, Sánchez 2021 (related blog post).

This is the coin type that occupied me much of last Thursday. The interest comes from it being a potentially non-Italian instance of an oath-taking scene. Such scenes appear during the Hannibalic War on both Roman coinage and that of certain Campanian cities which sided with the Punic forces.

This is the coin type that occupied me much of last Thursday. The interest comes from it being a potentially non-Italian instance of an oath-taking scene. Such scenes appear during the Hannibalic War on both Roman coinage and that of certain Campanian cities which sided with the Punic forces.

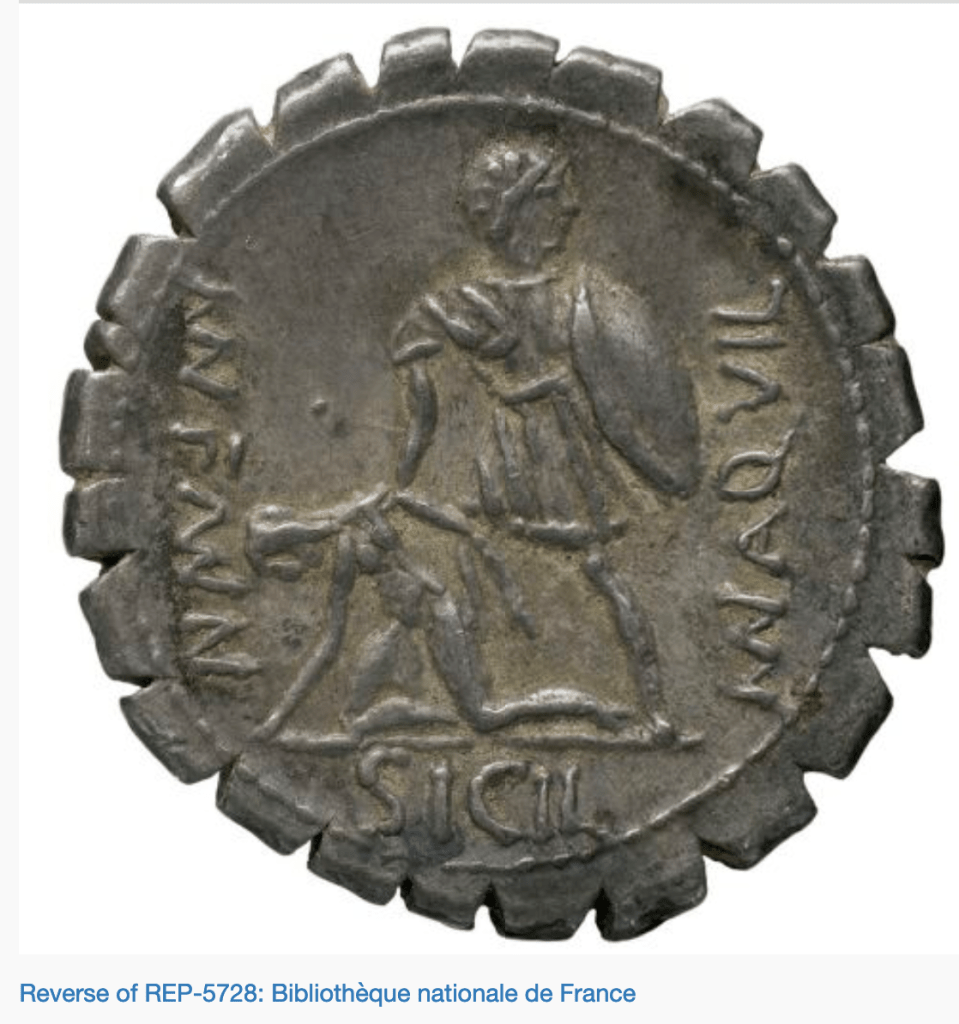

And was resurrected by the Romans probably about 137 BC:

But was then famously the iconography was taken over by the Italian allies during the Social War in the 80s BC when they broke with Rome.

The swearing of an oath on a pig to seal a treaty is well attested as part of Italic culture, perhaps most famously at the Caudine Forks incident. The legend of the type had previously been read on less clear specimens as FETIA and thought to refer to the fetiales, the priests associated with religious declarations of war and solemnizing the peace. All these ‘oath scene’ coins have been associated with the fetiales in the past. That’s somewhat problematic as such an oath could be sworn by the generals without such priests (again, see Cicero on the Caudine Forks oath).

Anyway, the new specimen above clearly reads EETI- and all the other reverse die specimens I’ve seen could be read the same way. EETIA must be Latin as the letter combination is unattested in Greek. It’s none too common in Latin. If the word begins EETI- one thinks of the various legendary kings and heros named Eëtion. They are associated with the Greek mainland or Asia Minor. Leypold said he bought his specimen in Amisus and because small bronzes don’t tend to travel far its usually attributed to that location or the general region. No other specimens find spots are known. The lack of a diadem or garland on the obverse head has lead to the assumption it was a portrait of a Roman commander. Speculation then commences about possible Roman commanders active in Asia Minor. The Roman certainly experimented with coinage in the region.

As we puzzle out the legend we might recall that “Accian” Vowels, i.e. the reduplication of vowels to indicate their long vowel length, do appear on Republican coins. [This type of vowel is discussed by Lucilius.]

And, even on provincial issues from Macedonia:

For the type of the last see BM catalogue.

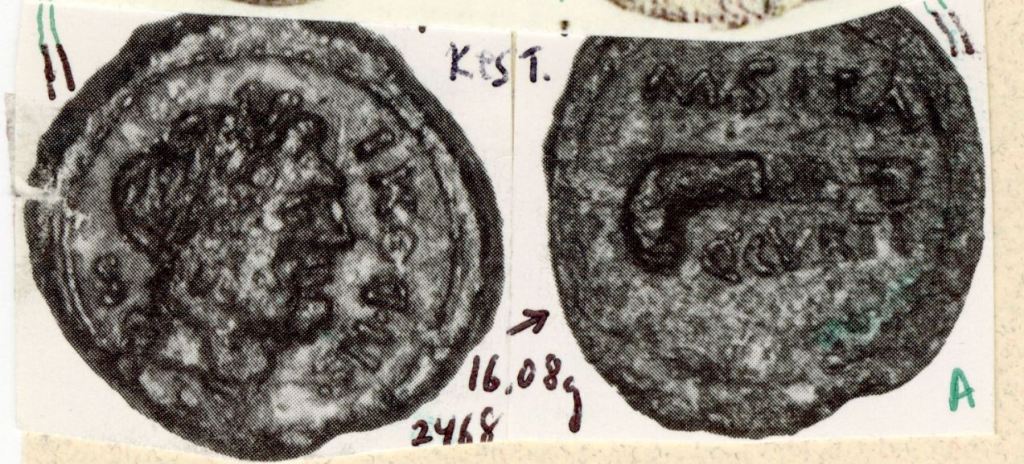

One other clue might be visable on this rather awful specimen:

On this specimen one can see what I think might be a Q under the obverse head. Q or PRO Q is a relativelycommon addition special issues and military coinage of this period. We’ve seen two examples already above. Here are two more from the Crawford sequence:

On this specimen one can see what I think might be a Q under the obverse head. Q or PRO Q is a relativelycommon addition special issues and military coinage of this period. We’ve seen two examples already above. Here are two more from the Crawford sequence:

I grabbed this last example because of the placement under the bust. If there wasn’t the assumption that it was from Asia Minor, I would have speculated Italic or at least Western Mediterranean origins. The type is closer to the Campanian imagery of two figures holding a pig above the ground than any of the Roman or Marsic scenes.

But finally, given that there only seems to be one obverse die and maybe about four reverse dies amongst all the specimens, not to mention the scarcity of the type, this must be a very low volume production. Why put all this energy into its manufacture?! Who benefited? Is it purely an ideological statement? If so, towards whom is it aimed?