Speaking Notes

Slide 1: For the best part of ten years I’ve been interested in all the places Dionysius breaks the fourth wall to break away from the distant past to remind us of his living present. In breaking the fourth wall he is acknowledging that he has readers, an “I see you seeing me” moment and he is also acknowledging that he exists in a time very different from the one he is describing. We at our great temporal distance are in effect watching him talk to his contemporaries about a shared reality while he is also talking to us about both the his distant past AND his contemporary reality. By regularly acknowledging his own distance and contemporary different he is invited us again and again to compare the two times, to notice the difference, and to draw meaning and relevance from that comparison. One of the most curious among them is a statement that Crassus only fell to the Parthians because he would not heed divine warnings.

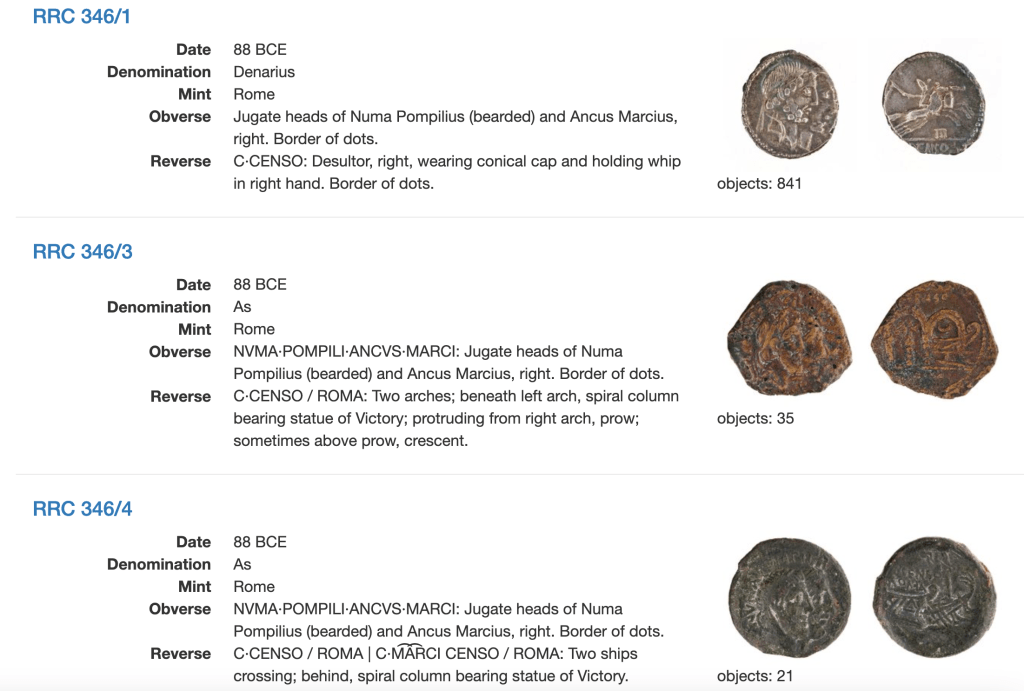

Slide 2: Yet, while I was trying to finish a pesky book on coins and clear the decks to get back to this type of historiographical question, other more dedicated minds were engaging with similar problems. I’ve particular admiration for Pelling on Regime Change and Parker on the Gods. I’m struck by how different is Pelling’s reading of Dionysius to my own. Not in care or intention or even in most conclusion, but rather the types of passages that interest us and seem most relevant for the question of Dionysius’ engagement with the contemporary. I was afraid I would have nothing left to say. [But of course we always do!]. Pelling begins with Dionysius’ distain for Polybius and ends by seeing Dionysius in a similar Augustan tradition as Livy and Vergil – not for or against but reflecting the Augustan age and its pre occupatons and dominant narratives.

In a forthcoming piece, I read Dionysius as engaging in polemical self positioning to allow himself to become the new “Timaeus” or rather Polybius prequel, just as Polybius attacks Timaeus in order to establish his own relevance and in the same piece read Dionysius’ views on autocratic rule as very much influenced by contemporary events. So to an extent I agree with Pelling’s much needed treatment of Dionysius’ constitutional views. Yet, I am also curious to the degree Dionysius is still a Greek historian writing in the tradition of Greek historiography.

Parker considers Dionysius’ views of the divine as a reaction to even rejection of past traditions. Overall he agree’s with Cary’s 1937 summary comments in the introduction to the Loeb volume that Dionysius is a true believer in divine intervention in human affairs, damning of atheists, and a distaste for Greek mythology and its shameful portrayals of the gods. Parker says I quote, “In consequence of his strong belief in divine guidance, Dionysius is reserved about the role of Tyche in world affairs.” Parker reads Dionysius as at a distance even in rejection of the tradition of Polybius, and even Livy. He hypothesized that after a period of great skepticism in historiographical and intellectual circles comes a re embracing of traditional religious views. Thus, Parker would place Dionysius and even Diodorus in a model of traditional belief and even anticipating the morality of Plutarch. Parker is apt in his selection of key themes but a bit like Pelling on Polybius, I’m not sure we should be so convinced Dionysius ‘believes’ what he says. In many ways belief and feelings are not the central concern. Dionysius is a master rhetorician in full control of his narrative. He has a purpose for saying what he says. He controls his authorial voice and is keenly aware of his multiple contemporary audiences. Thus, I propose in what follows to observe how he is controlling his presentation and why that might be significant both in determining why he assigns to the divine the roles he does.

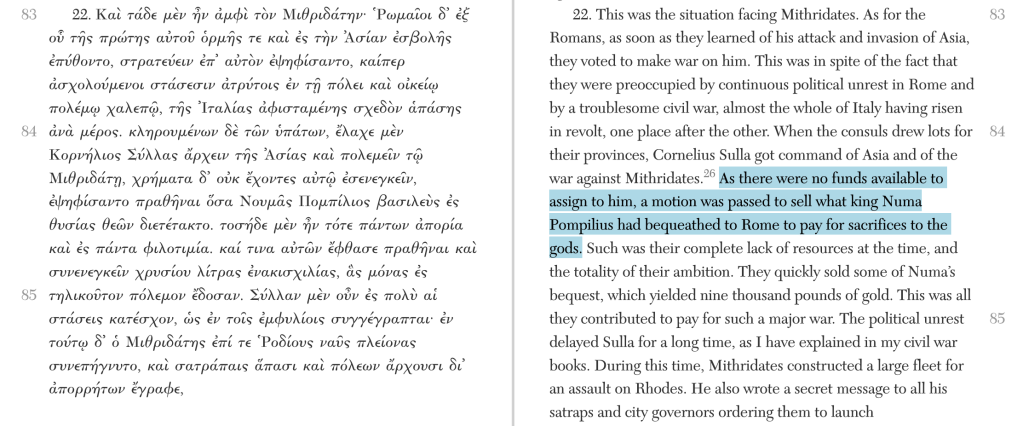

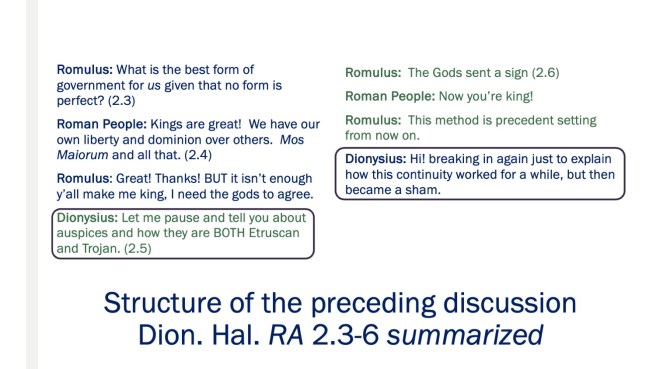

Slide 3: To structure this paper I’m going to start with this short passage and with a relatively close reading of the chapters leading up to this passage before returning briefly to this passage and then broaden out to other evidence and literary passages that might help us contextualize Dionysius perspective. Dionysius claims that Crassus was second to none as a commander, an odd memorialization for a man most often discussed as a power-broker, business man, and hoarder of immense wealth, not for his military prowess. Moreover, we know from Plutarch’s life of Crassus that he was committed to religious observation (at least if it was in his interests) having dedicated a 10th of his wealth to Hercules before setting out on his final campaign. His tithe provided enough food to feed every Roman for three months we’re told as well as all the other ostentatious spectacles. Dionysius ends this small digression with the comment that it would be POLU ERGON, much work, to explain how divine signs had been ignored EMAS CHRONOIS, in our times. Crassus become a synecdoche for all the earlier failings that go unmentioned. Yet we the audience are also invited to fill in the blanks from our own memories of recent events. We are invited to know, or even in terms of today’s pundits “Do Your Own Research”. We are being led to conclusions by a skilled rhetorician who obscures his own role as our guide. If you invite someone to find out for themselves whats ‘really in vaccines’ you’ve already convinced them there is a hidden truth to be found. As we are invited to fill in the long story of religious improprieties we the contemporary audience are already conceding that religion and its right observance are necessary and appropriate for good government.

Slide 4: On the slide I give a slightly flippant outline of the material, in the interests of time I’ll only hit a the most relevant points. You can find the whole text and translation on my digital handout. As we move through the outline the portion I’ll be discussing is highlighted in green. The Crassus passage comes within a wider meditation on forms of government and why and how Romulus as law-giver established the state as he did. This shouldn’t surprise us. Religion is almost always presented as key to the Roman constitution, even in Polybius’ skeptical treatment of rituals in book six, he regularly concedes the value of Roman religion for social cohesion and continuity of tradition. I’ve started summarizing at 2.3, three chapters before the passage in question. Romulus assembles the Roman people once the ditch, rampart, and houses are built to decide on a form of government. We’re not told where the assembly was held. Dionysius does not seem to be reflecting on any of the historical assemblies of the Roman people. He does emphasize that Romulus isn’t innovating but instead being advised by his grandfather both in the initiation of the conversation and what needs to be said. The rhetoric attributed to Romulus emphasizes themes of public versus private and internal vs domestic affairs. He dwells on the dangers of enslavement both figuratively and literally. He alludes to three forms of government common to barbarians and Greeks alike. He ends with a statement his honors are already sufficiently enduring; he stresses he will freely step away from the power he presently has.

Slide 5: Chapter 2.4 opens with another reminder that the speech had been advised by Romulus’ grandfather. The people go off to confirm among themselves and they deliver this response. This is super strange. The people are not a deliberative body at Rome. They listen to speeches, elect candidates, and vote yes and no on legislation and guilty non-guilty in trials. Deliberation is the bailiwick of the Roman Senate not the populus. Even in the Senate the ‘debate’ follows a rigorously controlled speaking order. The speaker who replies for the unified whole is not named. He has no characterization at all. Dionysius again wants to present a pair of set speeches, He is most comfortable exploring abstract concepts in the rhetorical genre. Leaving this response to Romulus anonymous and communal allows him to formulate his own answer to his own question in his favorite style without engaging in characterization or further mythologizing. The answer is relatively short by comparison with Romulus’ framing of the ‘question’, just 13 lines of Greek in the Loeb printing compared to more than 60 for the set up. Only three main points are made clear: kingship is acceptable because of (1) the wisdom of the ancestors (2) it has provided freedom internally and dominion externally, and (3) Romulus himself is worthy by deeds and lineage. I take from this confirmation that Dionysius’ emphasis on Romulus’ grandfather is no accident, but rather further emphasis on deference to mos maiorum and filial piety.

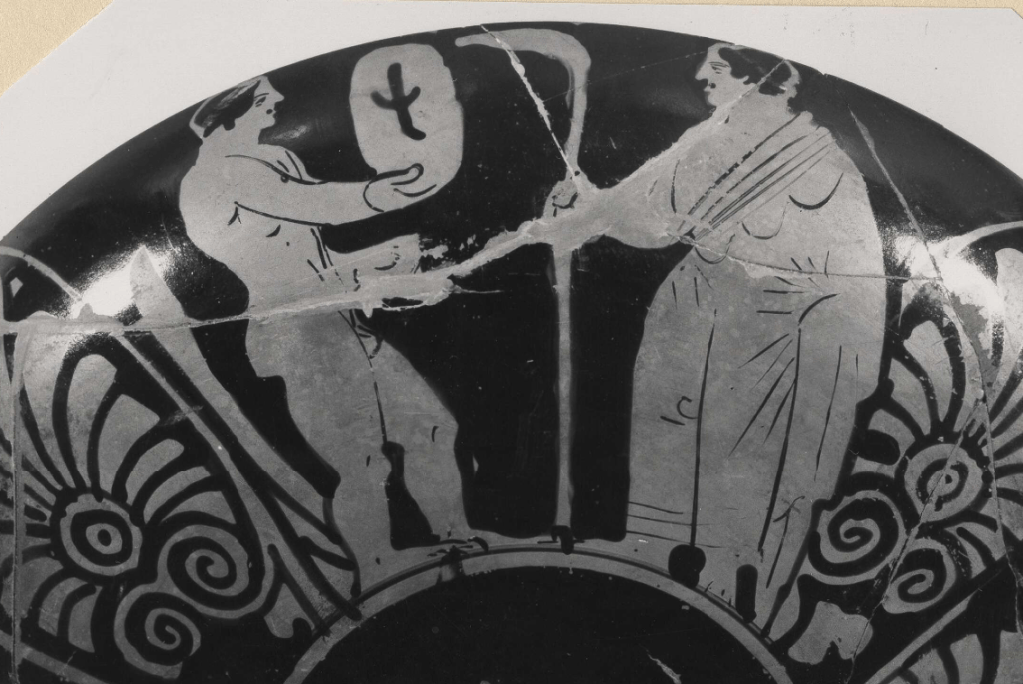

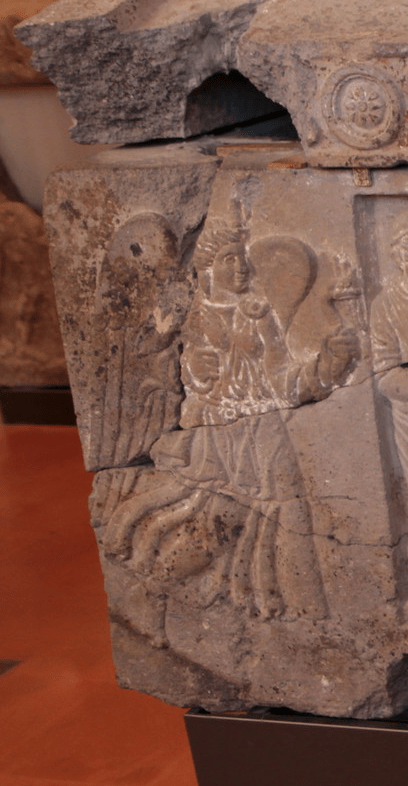

Slide 6: Dionysius is positively laconic (at least for himself) as he states in brief that Romulus would not accept the honors from the people no matter how much they pleased him without divine approval. Notice the combination of TO DAIMONION and OI OIONOI to describe the necessary pre requisites for Romulus’ assumption of the kingship. Dionysius goes on to use the very same vocabulary is used to describe Crassus’ failure to observe divine messages. DAIMONION is a favorite generic and all encompassing reference to divine agency. It is found in History and Philosophy almost from their inception in the Greek language. OIONOS can refer to any large bird of prey but is often found simply to mean omens or signs of any kind. I think in the Roman context and the context of these passages particularly the meaning of birds as a synecdoche for augury is particularly strong.

Dionysius has the people approve Romulus’ decision to consult the gods on the matter; making piety not only a characteristic of the leader but also his followers. It should go without saying this is completely ahistorical and Dionysius constructing an exchange between between ruler and subject without precedence in Roman traditional practices. More typically, the Senate referred religious questions to experts within the priestly college. I can think of no collective approval of religious action by the people that might have inspired Dionysius’ historical creativity here.

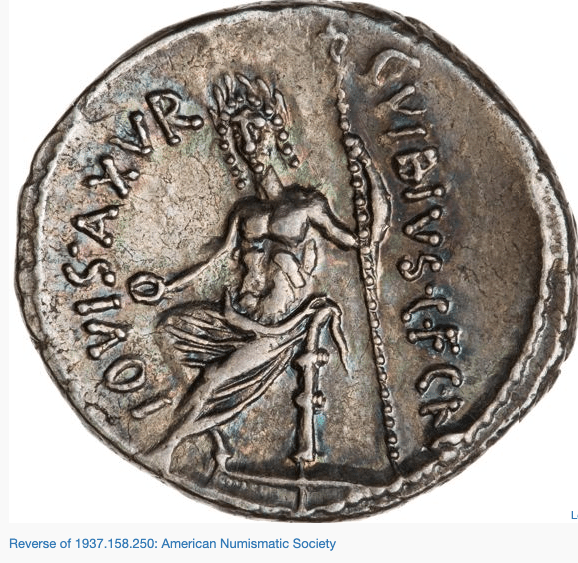

Chapter five has Romulus invoke Jupiter as KING to sanctify the use of kingship at Rome. Logical enough and yet again not a common form of address, we might have expected Optimus Maximus or even a whole list of patron gods . The best parallel I have found is in Cassius Dio where Caesar retorts to Antony at the Lupercalia “Jupiter alone is king of the Romans” (44.11.3). The quote is absent from other surviving accounts, but we may have an allusion in Nicolaus of Damascus’ Biography of Augustus (73) where Caesar says the diadem was more appropriate for Jupiter Capitolinus. Even if Dionysius is not trying to make us think of Caesar here, he is certainly drawing a direct connection between the role of the king and divine authority and ideology we won’t see fully expressed until the high Empire. (Trajan coin).

Slide 7: Who are these people Romulus was consulting and what gave them authority to determine the constitution of the state or sanction him to consult the gods on their collective behalf? Is Dionysius situating the Roman people with self determination or implying their sovereignty? I don’t think the text supports these readings. When Romulus had assembled the people to ask the question about the form of government, Dionysius used the term AGORA to denote the collective nature assembly. And when Dionysius sums up the speech he refers to the people as PLETHOS and when Romulus hesitates to receive kingship on their authority alone he calls them ANTHROPOI. We have no use here of DEMOS and it seems striking by its absence. It is only AFTER Romulus reports the sign, becomes king, and establishes a lasting precede that the language of a political body is used in the text. It is only now that the people become a DEMOS and their gathering a a proper EKKLESIA in Dionysius’ choice of language. Divine sanction seems to have been necessary in Dionysius’ mind for Romulus’ status but also for the establishment of the civic body as a body. The people and the gods make a king, but the king and gods also make a people into a legitimate civic body.

Slide 8: I’m now skipping over Dionysius’ extended digression on the auspices involving lightening, in which he endeavors to show is how ”scientific” especially geographical knowledge. The digression allows him to play cultural interpreter for his Greek audience, deepening his own authority on all matters Roman. The next portion of narration wherein Romulus reports the sign, becomes king, and establishes a last precede is very short before we have yet another digression on continuity of the tradition and its failure. The two digressions are doing very different work in the narrative. Whereas the first situates Dionysius as an anthropologist and guide to foreign esoteric practices, the second has Dionysius comment on the contemporary relevance of the past for the present. We can dismiss this as the rhetoric of the decline that justifies the augustan restoration, but we can also observe HOW Dionysius’ rhetorically brings his reader to concede to this world view, largely by refusing to engage with specifics.

Slide 9: Dionysius contrasts the authentic, even scientific, interpretation of the omens that were present for Romulus with the ritualized practices of his own day. Part of the disconnect is that the incumbent magistrates do not need to see the omen themselves, the responsibility for the observation is abrogated to some so-called “bird watchers” under state employ. These individuals lie and their lie is taken as a positive omen. Dionysius using direct authorial voice to leave us no doubt of the disjoin of what is said and the real events.

[CUT from actual talk: I’m interested in the apparent perjorative treatment of these ORNITHOSKOPOI and I’m hoping in discussion some of you might have ideas either who these individuals might have really been in Rome’s complex religious structures, I doubt they can be augurs based on their being ‘employed’, but perhaps I’m wrong. I’m also interested if you can help me nuance out the nature of distain and how it might connect to other polemical attitudes.]

Slide 10: Before Dionysius coming to Crassus his ultimate and best example, he engages in sweeping generalities. The consequences for ignoring divine will are evident on land and sea, in foreign and domestic conflict. All the recent suffering may be laid at the feet of a godless elite who go through the motions of religious observation without any true divine mandate. Are these elected officials really even legitimate leaders of the republic or have they stolen their positions through violence and charlatanry? The contemporary reader is left to fill in the gaps. Are we to think of Antony? Pompey? Sulla? Marius? Crassus is safe — the others all too charged in many ways. The long and the short of the passage is a suggestion a lack of piety by the leaders of the state is key to explaining Rome’s suffering.

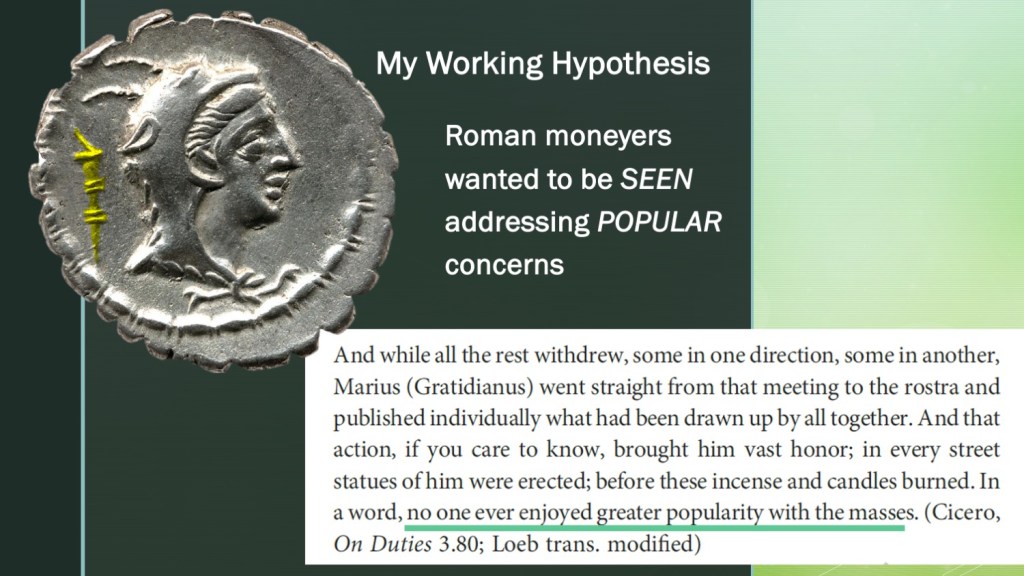

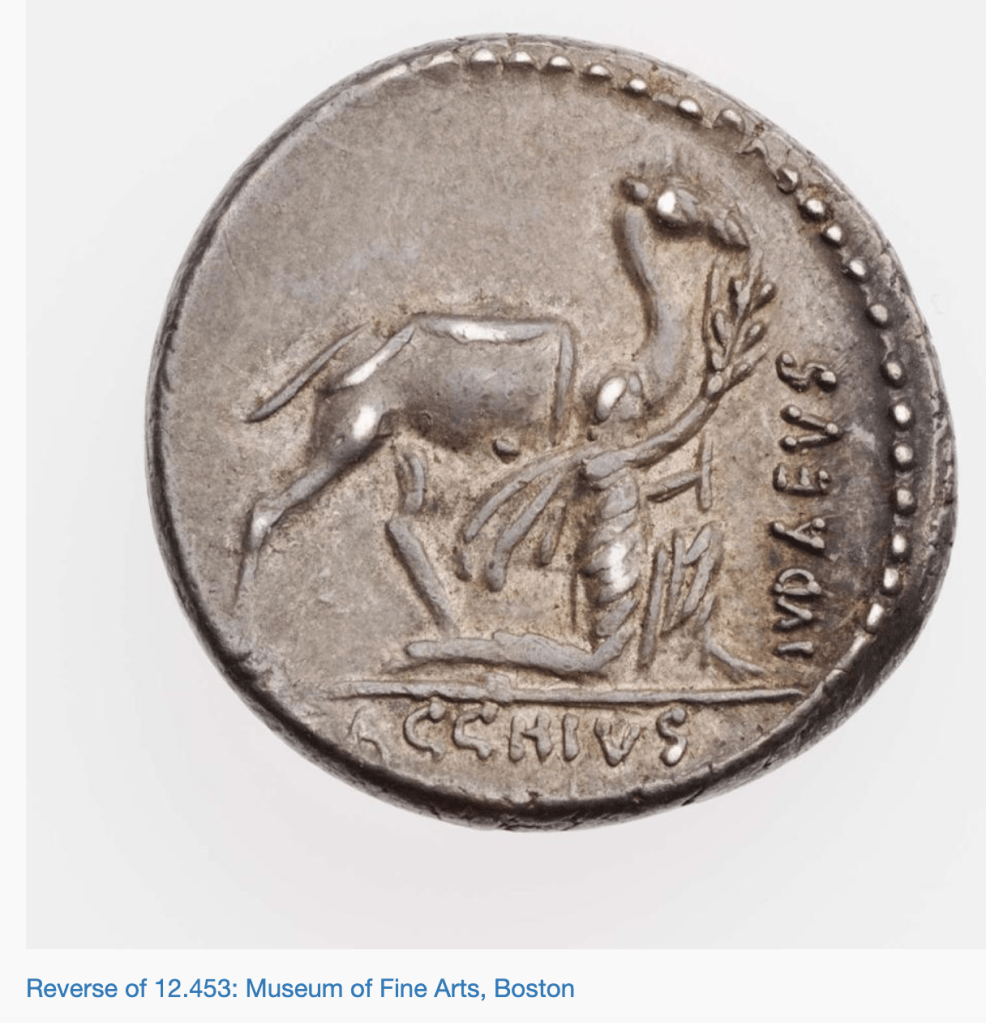

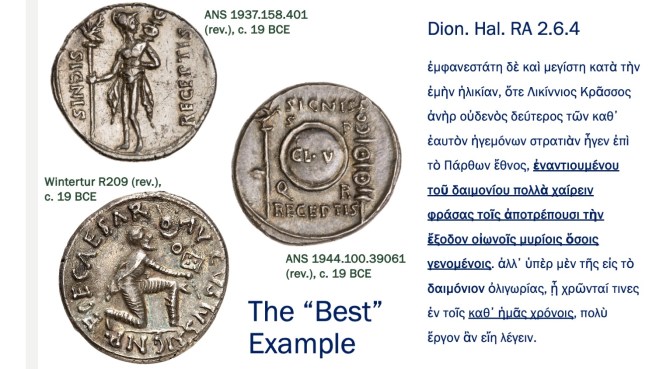

Slide 11: Why is Crassus safe? Dionysius’ choice of Crassus intersects with Augustus’ own intensive focus on the return of the Parthian standards as the symbol of his successful restoration of Roman power. The return is all over the coinage immediately after their return. Often associated with Mars Ultor and Augustus’ own Clipeus Virtutis which among other virtues celebrates particularly Augustus’ own piety.

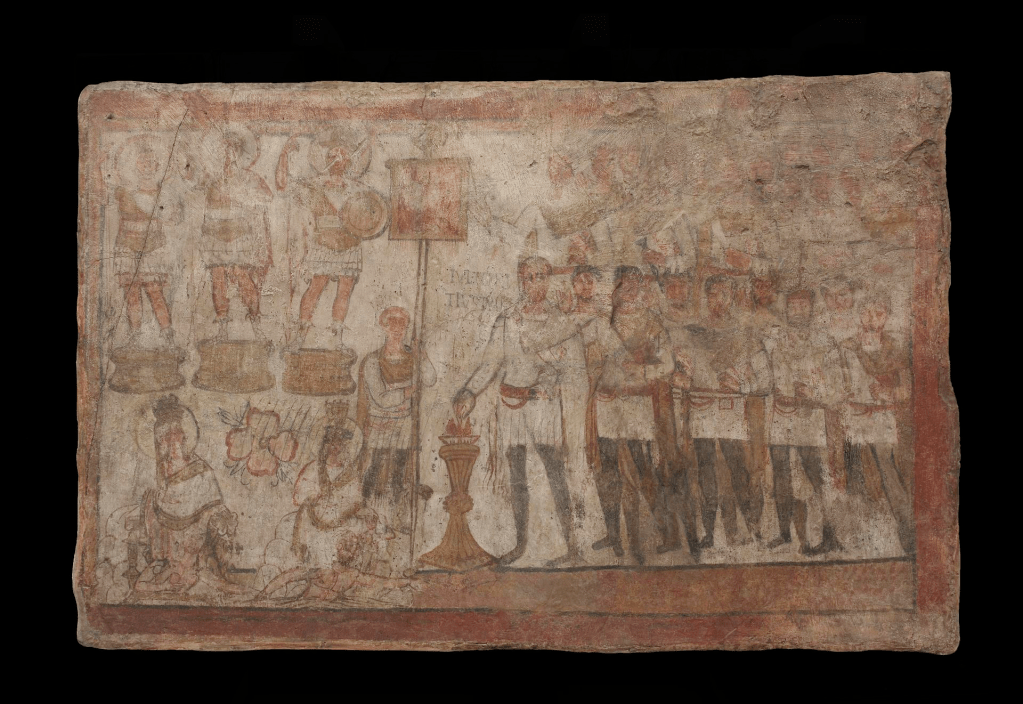

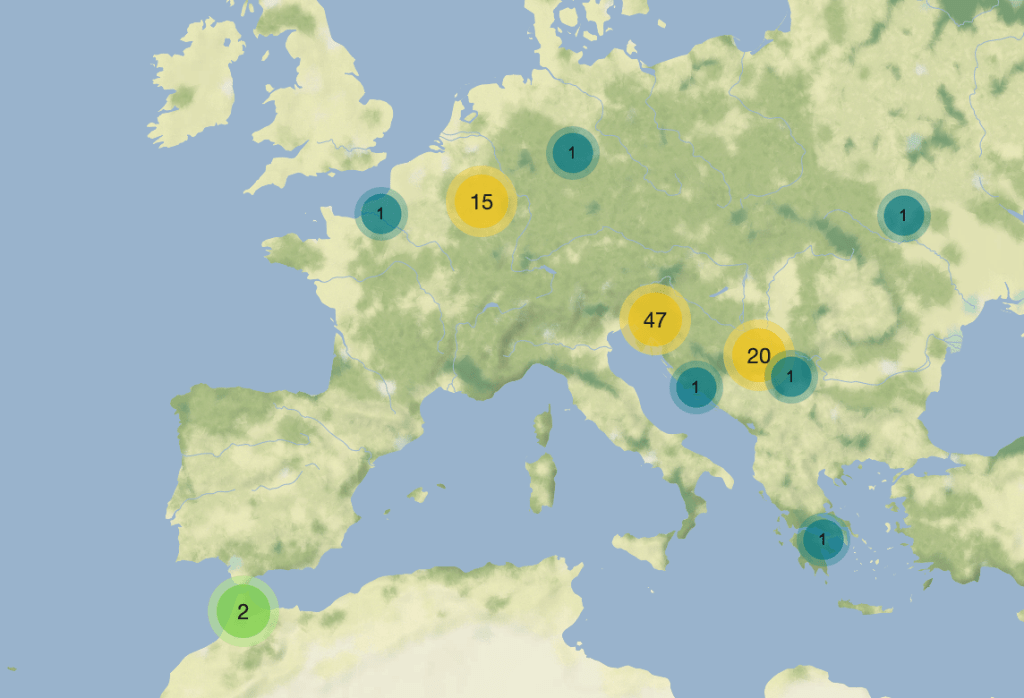

Slide 12: The Augustan celebration of the return of the standards was in no way limited to the coinage. Today the most famous image of the return is on the cuirass of Augustus in the prima porta statue from Livia summer residence, but in antiquity perhaps the most spectacular commemorations may have been on the triumphal arch in the Roman forum. Augustus’ arch or arches are now lost but at least one would have stood between the regia and the temple of Castor and Pollux. We think it may have looked something like this aureus with Parthians flanking Augustus holding out the aquila and standards. Augustus changed the primary meaning of Mars Ultor from a celebration of his avenging his father to his having Avenged Crassus’ defeat. Likewise, if as some believe this arch was originally built to celebrate the victories at Actium and Alexandria then we might be seeing the return of the standards also overwriting yet another civil war victory with a foreign diplomatic success. We cannot know precisely when Dionysius was drafting book 2, yet we do know he arrived in Rome shortly after the defeat of Antony and witnessed first-hand the transformation of the urban landscape and political norms over the next decades.

[Cf. Ovid Fasti 5.560-585 on change of Augustus’ relationship to Ultor and allusion to Romulus]

Slide 13: As Dionysius finishes with Crassus, he brings us back to his historical narration and prepares us to transition into a description of Romulus’ constitution. The words that open that next chapter are at the top of the slide: “thus chosen king by both men and gods”. Dionysius’ Romulus was made king was not his own strength or characteristics alone, nor just popular opinion, but instead a specific combination of divine and human recognition of his qualities and confirmation of his role as king. I see here a precursor to the themes more fully developed by Dio. Dio Book 53 has the famous explanation of the young Caesar’s choice of Augustus as his honorific. Just before the passage on the screen Dio introduces the Romulus theme by connecting Augustus’ home on the Palatine to the location of Romulus’ hut. Next we learn that the young Caesar originally wanted to be called Romulus but had to reject it because of the ‘kingship’ overtones of the name and thus chose instead the religious honorific of Augustus. Dio works to translate and nuance the name for his audience. Dio never fully abandons the Augustus-Romulus connection, even suggesting during his discussion of Augustus deification that the connection was supported perhaps even originated with Livia herself. There is a wide literature on Augustus’ use of Romulus and I propose only to nod in its general direction today to suggest that Augustus was very much in the mind of Dionysius in the construction of this portion of his narrative and his view of the role of the divine.

[Poletti, Beatrice. 2023. “Augustus and the Myth of Romulus (on A. Castiello, Augusto Il Fondatore: La Rinascita Di Roma E Il Mito Romuleo)”. Histos 17 (April). https://doi.org/10.29173/histos552. The Dio passage is sent amongst events of 27 BCE. And Sertorius does not attribute the desire to Augustus himself but only a popular suggestion (Aug. 7 cf. Florus 2.34.66)]

Slide 14: Even if Augustan Rome was steep in the rhetoric of religious renewal, what I want to emphasize is how striking it is for a Greek historian or really any historian to attribute historical events to divine cause. This is very different than how the Greek historians utilize the persona of Tyche; Dionysius’ TO DAIMONION is no theoretical personified abstraction or authorial-thought experiment. Instead, he makes a bold assertion in the authorial voice that religious ritual, the very type of action Polybius happily dismissed as a means to control the lower classes, is in fact a means of ascertaining the will of the gods and its neglect may be a root cause of Rome’s problems. Even Livy who happily reported prodigy after prodigy, does not typically attribute Rome’s fate to supernatural powers. We could brush Dionysius invocation of the divine aside as another sign of his lesser value as a historian or his sycophancy, but I think it is worth pondering this unusual authorial intervention and contextualizing. Dionysius knew his rhetoric and he knew how to stay away from anything that might be too controversial and he certainly has read his Polybius. His near contemporaries such as Nicolaus of Damascus and Livy thread the needle of religiosity very differently. Dionysius need not have included these authorial statements to accomplish his authorial goals so why are they here? As I said at the beginning I am less concerned with what Dionysius believes in his heart of hearts as I’m skeptical we can know this, but rather I’m interested in why he may express these ideas in these particular ways in this particular context.

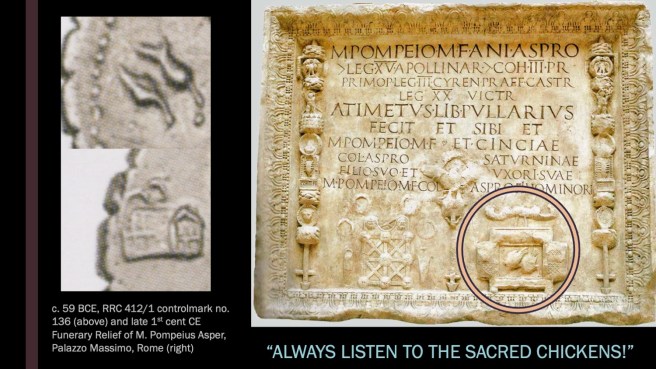

Slide 15: While it is hard to escape the Augustan rhetorical echo chamber, I think one way forward with this passage is to situate it along side other narratives of Roman defeats. Dionysius’ choice to center Crassus’ disregard for the omens as the cause of military disaster calls to mind another Roman disaster more commonly attributed to impiety, the battle of Drepanum in 249 BCE before which P. Claudius Pulcher allegedly tossed his sacred chickens overboard saying “if they will not eat, let them drink!”. The story is regularly used not only to explain how the Romans could possibly have lost but also as a morality tale about the importance of Roman religion and occasionally to illustrate the arrogance of the patricians or this particular gens. The drowning of the sacred chickens appears four times in Cicero, three times in later epitomes of Livy, as well as in Suetonius and Valerius Maximus. If the epitomes of Livy are true to his text, we have to imagine that this is a situation where Livy himself broke from Polybius as his primary source for events. Polybius is our oldest source for the battle, the narrative is complete, and there are no sacred chickens, alive or dead. Cicero never raises the episode in his surviving oratory, only in his philosophical treatises on Religion all composed under the Caesar’s dictatorship. I take from this that the episode was in common currency and ‘good to think with’ but not precisely something one could invoke in a republican political argument. Dionysius likely treated the battle of Drepanum in his late and now largely lost books. I’ve often thought if these survived in full instead of just the earlier more legendary books we might all have a v different option of Dionysius as a historian.

[CUT from actual talk: Dionysius’ only surviving mention of Drepana is a discussion of Aeneas stopping there to build cities for earlier Trojan refugees in book one. Unlike other writers he does not in any way connect the place to the death of Anchises, and he refutes an earlier tradition whereby the city building there was necessitated by women burning ships to end the grueling journey. I detect no foreshadowing of Pulcher’s naval disaster here.]

Slide 16: We do, however, have yet another digression from Dionysius in relationship to Romulus’ state building activities which looks ahead to the disaster at Cannae. While Dionysius is not explicitly engaging with the contemporary here, he is still breaking the fourth wall to again interpret Rome for a Greek audience through comparison with Greek history. Answering in a new way the Polybian question of why did they succeed where we did not. He is also by drawing events far ahead in time than his subject matter, explicitly drawing attention to his own temporal distance from his primary subject and how deep time connects to much latter historical events.

Here Dionysius refutes that the Roman recovery from this disaster had anything to do with Tyche or divine favor (cf. Polybius 1.63.9). Credit instead is given to Romulus’ foresight to keep Roman citizenship open to those deserving of the honor. He attributes the downfall of Sparta, Thebes and Athens to their not having similar means of restoring their manpower. What is missing from this passage is any engagement with why the disaster happened in the first place. Polybius spent the whole of book six outlining the Roman constitution, a project not unlike what Dionysius is undertaking himself in Book 2. For Polybius book six was necessary to explain Rome’s recovery from Cannae: the recovery isn’t about numbers, but about social and military structures, the Roman constitution in the broadest possible sense. Dionysius uses Cannae to highlight the value (and uniqueness) of Rome’s relatively open citizenship, he doesn’t care particularly about the disaster because unlike Crassus’ failures it has not direct resonance on contemporary events, but as a foreign resident at Rome the possibility of accessing Roman citizenship was likely a deeply personal question. Holding up Cannae as a reason for that openness can only aid the delivery of his message to contemporary audiences, and he’s perfectly happy to deny divine agency in this instance.

Slide 17: We’ve had a deep dive into just a little bit of Dionysius, but does any thing we discussed really relate to this conference? And can I justify my original title? Maybe. In my most recent book, I dedicated a half a chapter to the pervasive religious claims Romans make justify their dominion. The nature of the book necessitated a focus on coins, but I opened my discussion with a few passages I considered critical illustrations, the portion of Livy’s preface on Mars, Vergil’s prophecy of Jupiter, and a great bit from Cicero’s Haruspices. Robert Parker in his 2023 Histos article felt a similar impulse to point to to the same pervasive trope and instead chose to use a line from Horace Odes (3.6.5). Parker is not wrong about the power of this quote: “You rule, because you act as second to the Gods”. The use of therm MINOREM to refer to the Romans inherently casts the gods in the role of the MAIORES, the greater ones, or ancestors as we typically translate the Latin term. IMPERAS recalls Imperium and Imperator and the dominion over others that those terms imply. GERO is a verb of action not a state of mind. It is of course the same verb we find at the beginning of Augustus’ account of his things done, the RES GESTAE.

Dionysius without question engages with this trope. Deliberate acts of piety, both divine and filial, are necessary preconditions for Roman success, but I am not sure he holds them to be sufficient, either to explain Rome’s rise to power, i.e. historical causality, or even that he holds these truths as a personal belief system or theology. The questions I want to address as I continue to develop this work in progress is the nature of Dionysius’ Tyche. Is it closer to Roman Fortuna a goddess often more closely associated with divine blessings than chance? Was Parker right to distinguish Tyche in Dionysius from the Gods? And to what extent can we disentangle Dionysius’ individuality from the messaging of the moment?

I hope I’ve given us some food for thought and lively discussion in this work in progress. I look forward to your comments.