[Part Human (me), Part Machine (google) Translation]

“The discovery of this hoard took place by chance in the spring of 1890 at La Bruna[1] in the municipality of Castel Ritaldi, a few steps from the Tatarena ditch, almost in the center between Spoleto, Trevi and Todi, in the heart of Umbria.

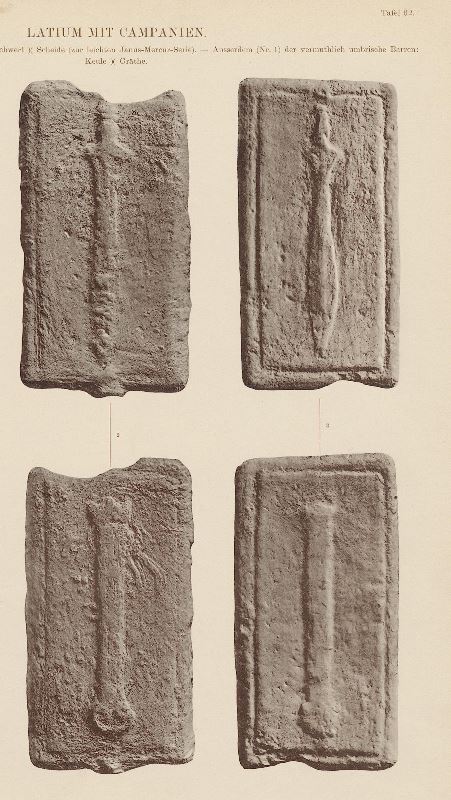

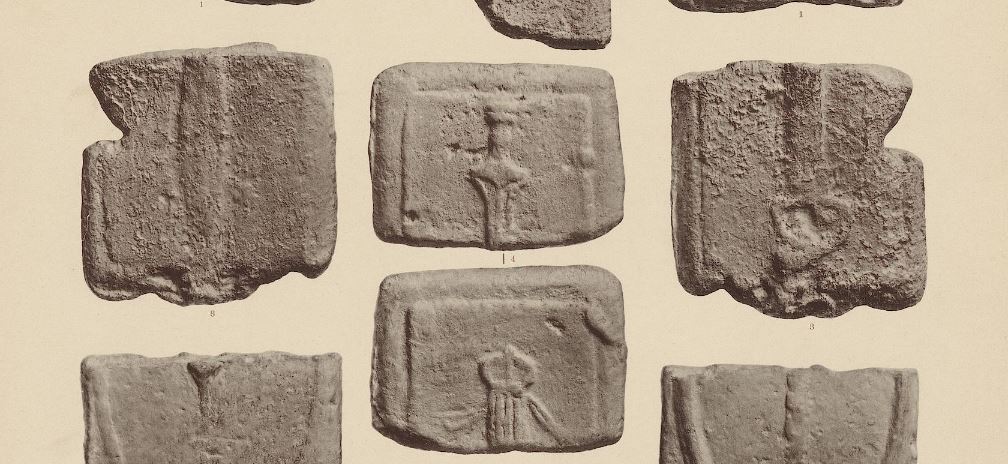

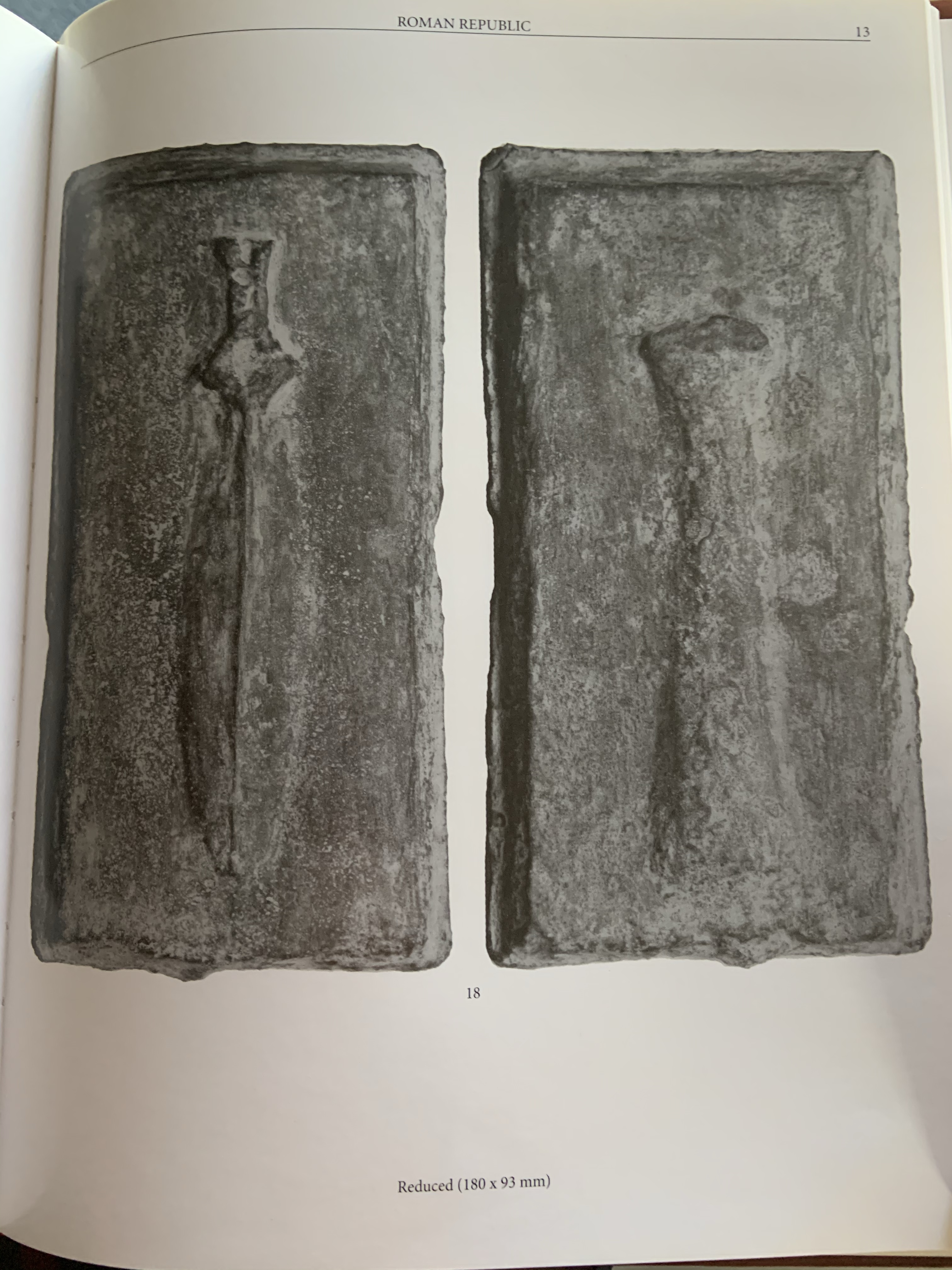

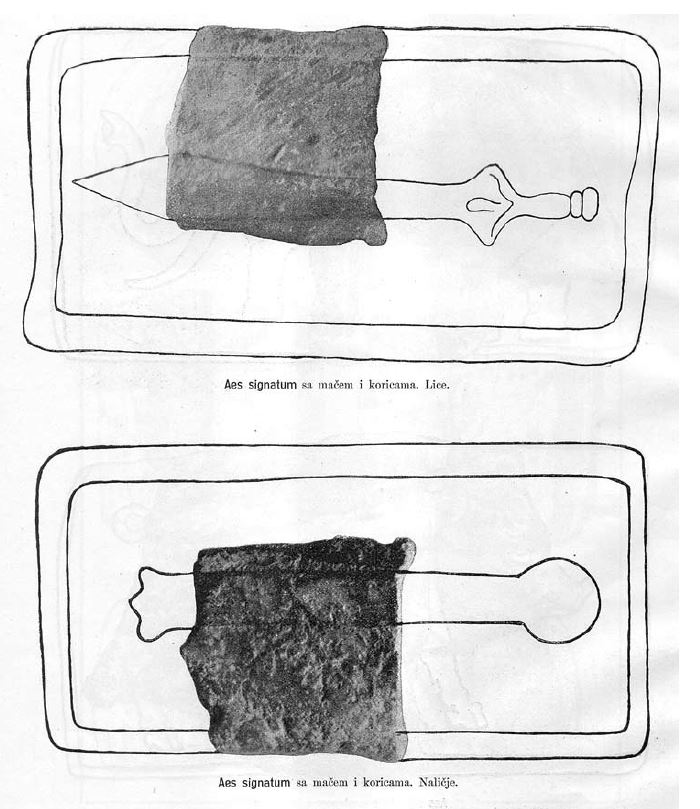

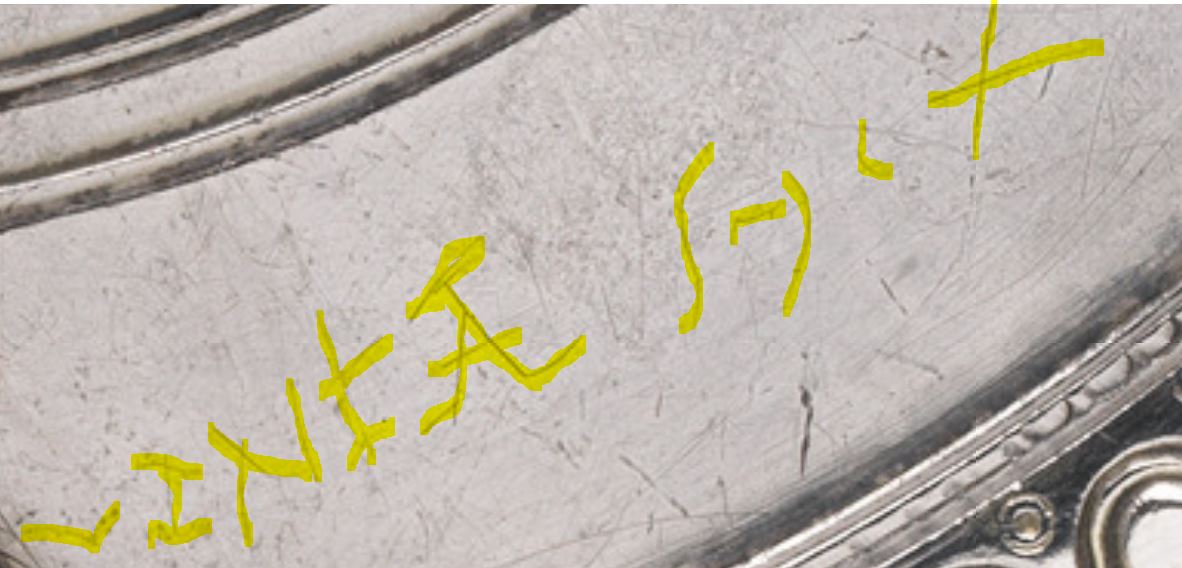

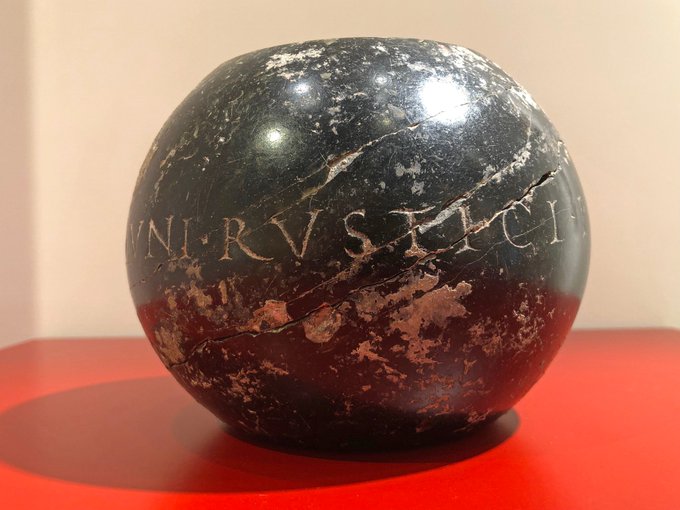

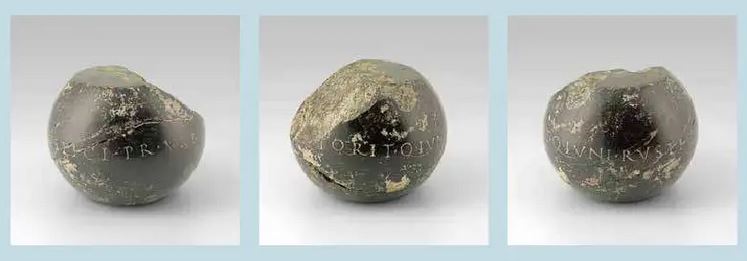

“A farmer, hoeing the earth, first came upon the bar shown on plates 4-5, which in fact presents the trace of the hoe on the basin of the tripod, then found four asses of the type shown on plate 14 [Apollo/Apollo]. He immediately took them to his patron, a certain Mr. Francesco Venturi, and the latter, on the next day, that man found himself at the find spot, poking the ground and looking more closely. He picked up all the other pieces that make up the treasure: that is, four other whole bars of aes signatum, two broken bars, plates 12-13, the piece of aes rude, plate 1, and four other libral asses, together with a few fragments of clay pots and some animal remains.

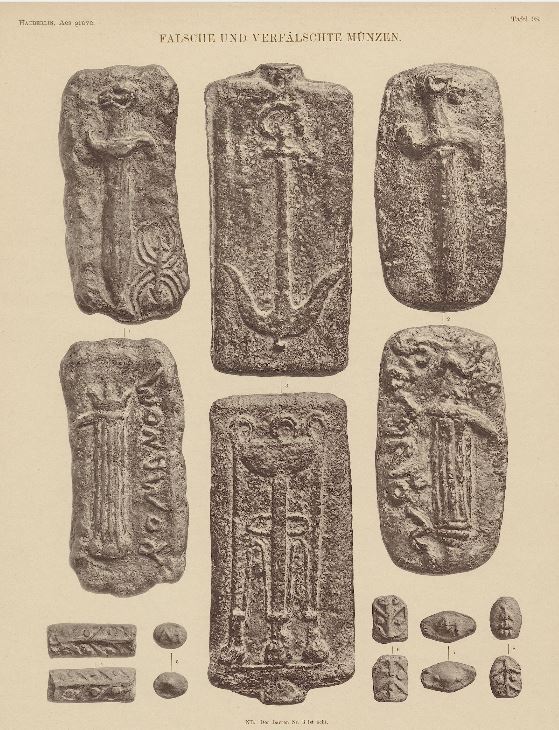

“The said Mr. Francesco Venturi brought the precious deposit to Rome, and showed it to the General Directorate of Antiquities and Fine Arts. There those pieces were believed to be false, and a hoax; and the same erroneous judgment having been confirmed to Venturi also by a well-known Roman antiquarian, he returned dejected and turned back to his own country.

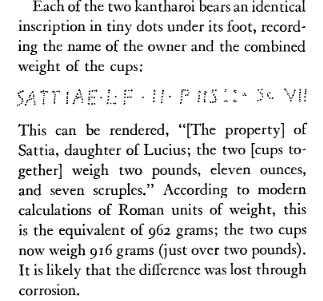

“Venturi retained the discredited objects until the end of November, when, having come into contact with the expert antiques dealer Mr. Giuseppe Pacini of Florence, could soon, and to his no small satisfaction, conclude the sale of the entire treasure. The merchant Pacini paid a large sum for it (about L. 9000 [equivalent to more than $18k today]), and he was not wrong to judge the find above suspicion. When he came to show it to me, I did not believe my eyes, seeing pieces of such extraordinary rarity, in such preservation, and with patina and such characters, as to leave no doubt about their authenticity.

“I was able to study this illustrious deposit in the short time it remained in the hands of the merchant Pacini; I took the photographs, slightly reduced, which served to the annexed photo-etchings, and had the casts of every single piece executed in the workshop of the R. Etruscan Central Museum, in anticipation of the further dispersion of the originals. Our Museum, due to lack of funds and the natural claims of Pacini, could no longer aspire to such a purchase. No later than early January, Mr. Pacini had found the buyer of the entire closet in the person of Dr. Tommaso Capo, a well-known lover of Rome, who has already begun the dispersion too, putting a part of it for sale in a public auction.

This is the true story of the discovery, and the ups and downs so far suffered by this hoard.

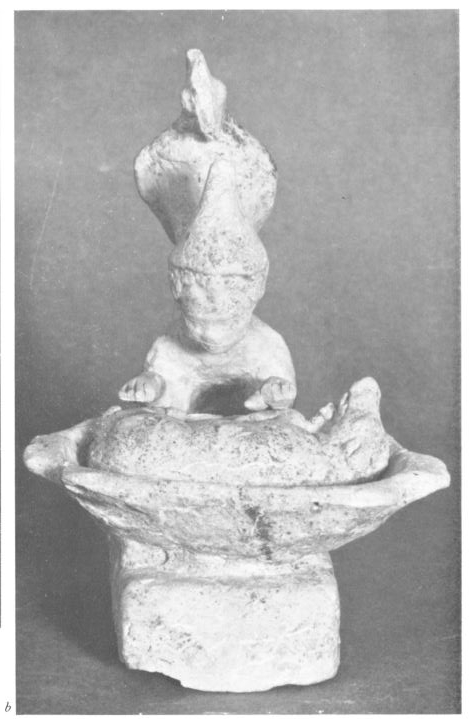

The fragments of the vase and the animal remains collected together with the pieces of aes grave were recovered by Mr. Giuseppe Pacini, following my expression of interest and sold by him to me. Shortly, I will exhibit them in the Central Etruscan Museum, together with the aforementioned casts; meanwhile I offer here the detailed description:

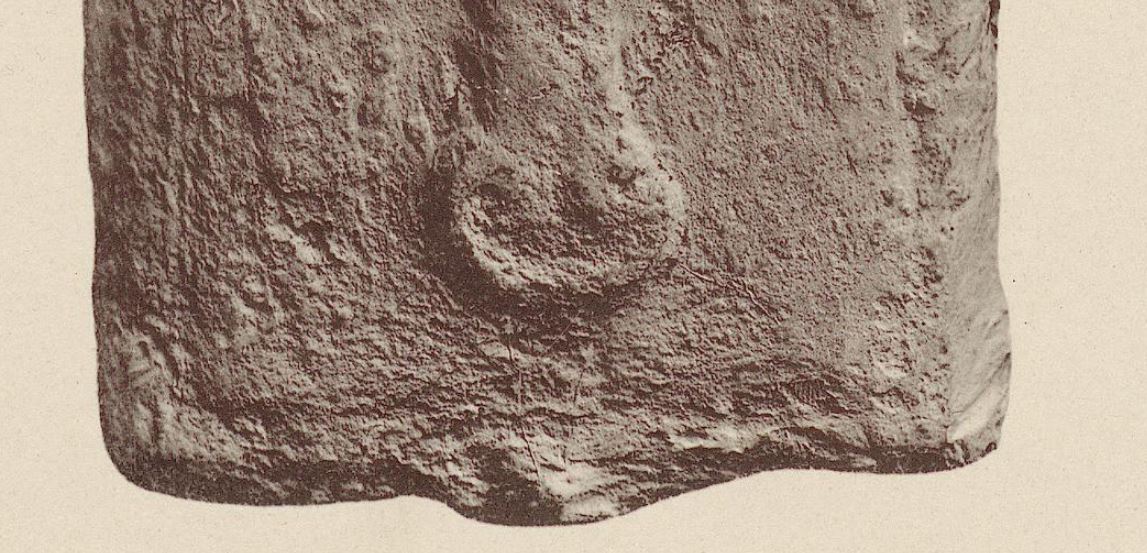

a) Two fragments of a large and robust dolio of primitive dish. The thickness varies from 0.027 to 0.035; the largest piece measures 0.09 X 0.21. The clay is almost black on the inside (soul) and reddish on the outside.

b) Band amphora loop (0.05 wide), attached to its mouth. It can be assumed that the mouth of the vessel had a centimeter diameter. 15 to 20. The clay is of an ashen-like fine mixture with a brick red outer coating.

e) Fragment of an ordinary black bucchero bowl, externally brownish, perhaps lid of the vase b; presumable diameter 0.15.

d) Fragment of the mouth of a midsized olla in ordinary red earth (thickness 0.07).

e) Bottom of a very fine yellowish earthenware vase, likely coming from a small olla or an Italo-Pelasgic cup.

f) Fragmentary femur of a horse.

g) Other leftovers of animal skeleton, and horse tooth.

“Here is the description of the seventeen monetary pieces that make up the actual treasure: …”

[1] La Bruna, about 11 kilometers from Spoleto, is a small place, with a church and an inn, which is marked on the military topographic map.

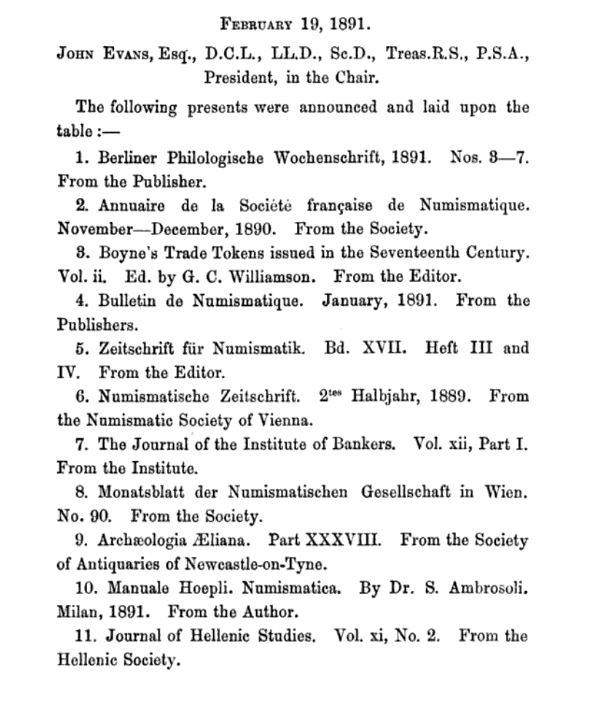

Interestingly Capo sent a catalogue of his collection this year to the Royal Numismatic Society:

BECAUSE…

It was a sales catalogue and he wanted buyers:

Capo, Tommaso. 1891. Catalogo delle monete greche, romane, primitive, consolari, imperiali, italiane medievali, moderne possedute dal Dott. Tommaso Capo, che si venderanno al pubblico incanto per cura del Cav. Ortensio Vitalini, numismatico in Roma, a principiare dal 9 marzo. Roma: Tipografia A. Befani.

(Links to WorldCat entry) And, thank goodness, the ANS has a copy and I will get to see that Tuesday. More then I’m sure.

And of course he found them as Crawford in CHRR (16) reports that most of La Bruna is now in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin… BUT, Berlin is supposed to be in CRRO and at least some of these pieces aren’t there (Eagle/Pegasus for example). Perhaps Berlin collection is not fully digitized? One of the Anchor/Tripod type is online and it was acquired in 1940 from Haeberlin. So perhaps Haeberlin was the primary buyer at the Capo auction?

Needs checking.

The report of Capo’s sale is in the same volume of RIN as Milani’s hoard report above!

Capo’s status/reputation as a dealer seems confirmed by this footnote.

But here he is described as a passionate numismatist and medical doctor. But the context suggests pieces that passed through his hands may have been ‘improved’.