So in the last blog post I complained about not having enough context, but sometimes context doesn’t help, but rather confounds.

The following tessera is from Agrigento and we even know the niche in the wall of a house into which it seems to have been intentionally deposited (as a ritual object? perhaps repurposed?!).

Full publication and source of all images:

Francesco Belfiori, « Su alcuni depositi rituali di Agrigento: prassi sacrificale e «riti di costruzione» in ambito domestico nel Quartiere ellenistico-romano (Insula III, Casa M) », Mélanges de l’École française de Rome – Antiquité [Online], 131-2 | 2019, URL : http://journals.openedition.org/mefra/8837; DOI : 10.4000/mefra.8837

It seems to read:

ARTEM ‘. AELIA . S

SPECTAVIT

AD . D . VI . K. MART. CO

I agree with the original publication that the first name is probably abbreviated form of Artemidorus or similar Greek name of an enslaved person. The second name they suggest Aulus but don’t committ. I feel I clearly read AELI and then what is probably an A missing its cross bar. The AE are in ligature. What I don’t understand is the enslaver’s name should be in the genitive of possession. No genitive ends in A or AS. The final CO in the third line is also a mystery. The letter forms are far sloppier than on most other similar tessera and it may be unfinished as the fourth side has no consular date. So…

Maybe it was just a bad piece of work someone shoved into a crack in the wall before starting over? In the image below the tessera was found in niche (hole?) 15a. So basically at floor level.

I’m wondering if the inside of the whole of a bone tessera like this might contain any trace elements of fibers or metal wire or lead or whatever was inserted into it and if we could now with our present technologies swap and test for this…

This next tessera is from Pompeii, one of two from the city thus far. It was found in the Basilica (reg. VIII, I, I) during the 1960 excavations, but the exact conditions of deposition are not clearer. I like this as it seems to fit our assumptions that these objects are part of the world of business transactions, particularly for large payments in coin.

Soldovieri, Umberto. “Un’inedita tessera nummularia da Pompei.” Sylloge epigraphica Barcinonensis: SEBarc (2020): 195-198.

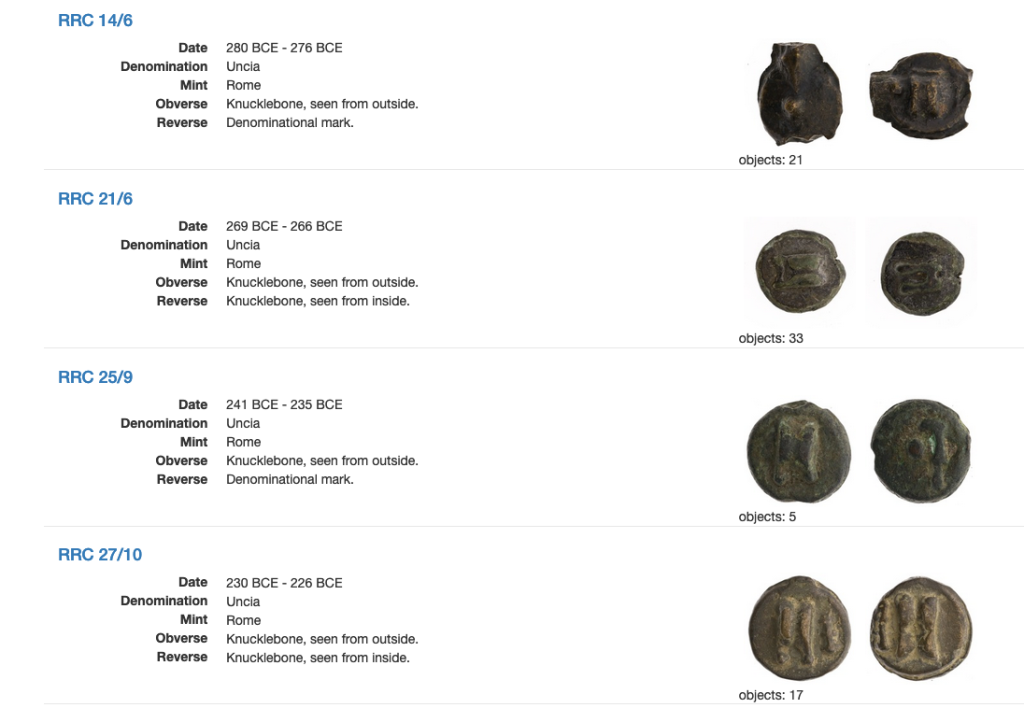

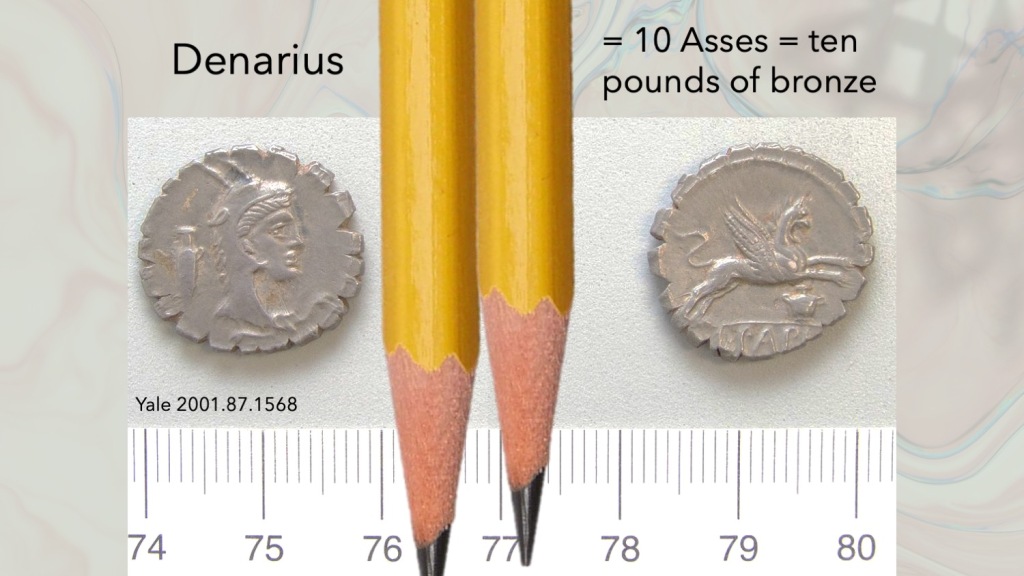

Part of what is fun about this object is that the enslaver’s name is Papius and that consular year is 79 BCE. The same year (Crawford estimated) that L. Papius was moneyer in Rome (RRC 384/1).

I want to leap to conclusions about why this might be the case, but one tessera does not a pattern make and so I will withhold speculation. (Rare for me I know!)

I’ve requested via ILL

Pace, Alessandro. “Tesserae nummulariae da Pompei. Un approccio contestuale.” Epigraphica 1, no. 1 (2022): 327-340.

And I hope it offers more details.

The other Pompeii find was from October 1878 and in “bedroom” in reg. 9.6.4-7. This doesn’t really narrow it down v much.

We know that excavations that October were happening in ix.6.4.x so that is a candidate… But they were also happening in ix.6.5.d and g, so that doesn’t really narrow anything down. I’d love to know more about associated finds…