Whelp. I now feel I have something to say about the Vicarello find that probably should be PRed, so we’ll have to have some stuff for the bibliography of that article. Not to mention reading it all to make sure I’m not intending on saying something in print that is too foolish. I’ll add to this post as I find more.

On the coins

Marchi 1852, …Acque Apollinari… (fully transcribed also on wikisource)

Haberlin’s notes are invaluable as he reports where some vicarello coins ended up, where Garucci and Marchi conflict in their testimony.

Taylor, Rabun. “Wheels, Keels, and Coins: Aquae Apollinares (Vicarello, Lazio) and Patterns of Pilgrimage in 3rd-Century Italy.” Ancient Waterlands, 2019, 225–44. doi:10.4000/BOOKS.PUP.40645. (academia) VERY USEFUL. VERY WELL ILLUSTRATED.

Falkenstein-Wirth Vera von. 2011. Das Quellheiligtum Von Vicarello (Aquae Apollinares) : Ein Kultort Von Der Bronzezeit Bis Zum Ende Des Kaiserreichs. Darmstadt: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. [coin chapter requested via ILL]

Colini, A. M. “La stipe delle acque salutari di Vicarello.” Rendiconti della Pontifica Accademia Romana dr’Arcbeo1ogia 60 (1968): 35-56. [Discussed in past blog post; on file.]

Tocci, L. M. 1967-1968. “Monete della stipe di Vicarello nel Medagliere Vaticano.”Atti della Pontificia Accademia Romana di archeologia40: 75-81.(PDF on file)

Francesco Panvini Rosati (on file in collected works)

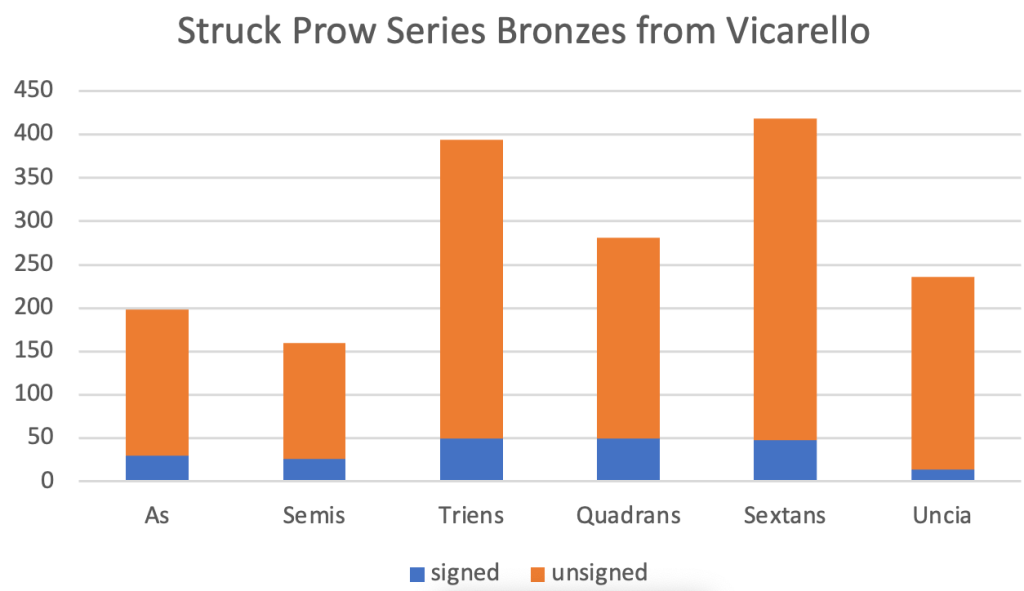

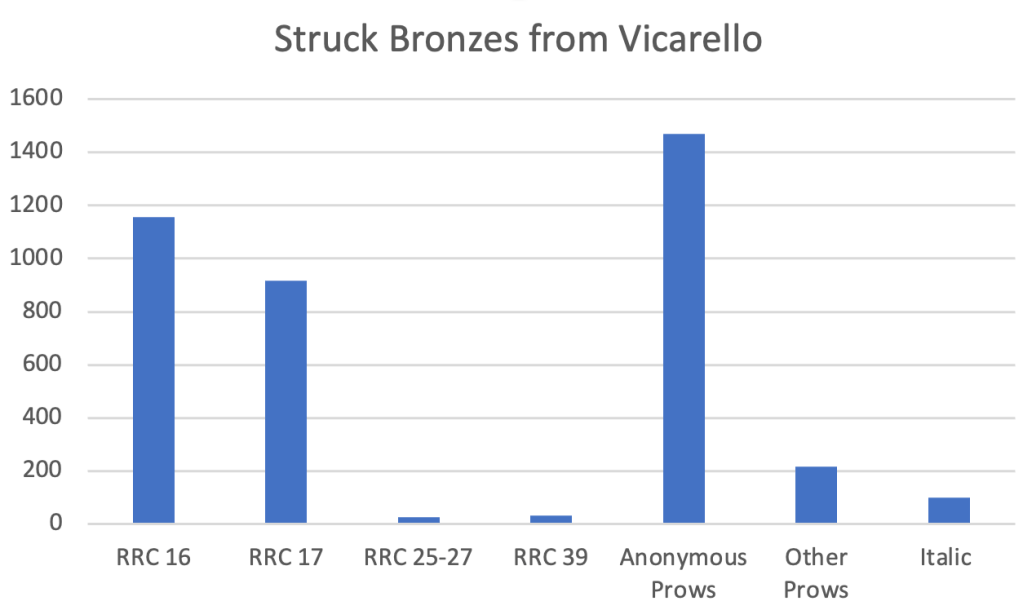

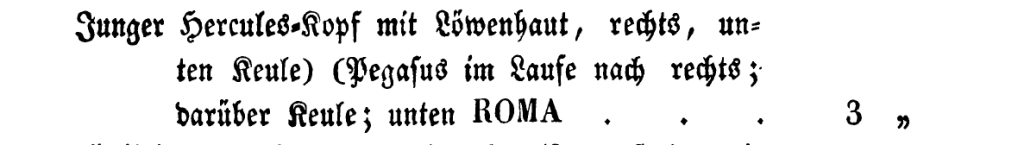

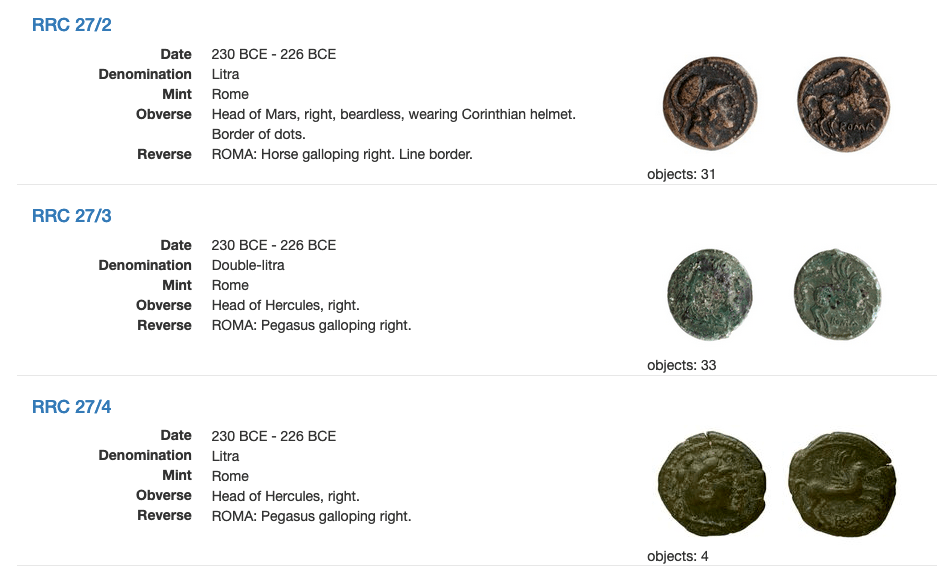

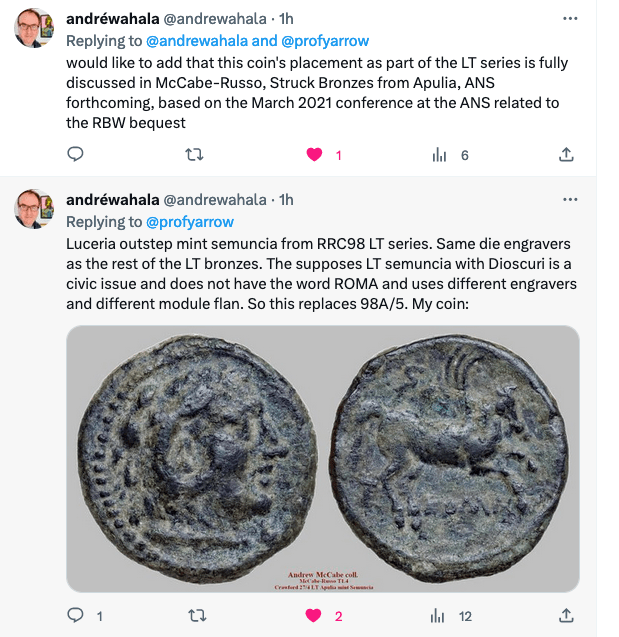

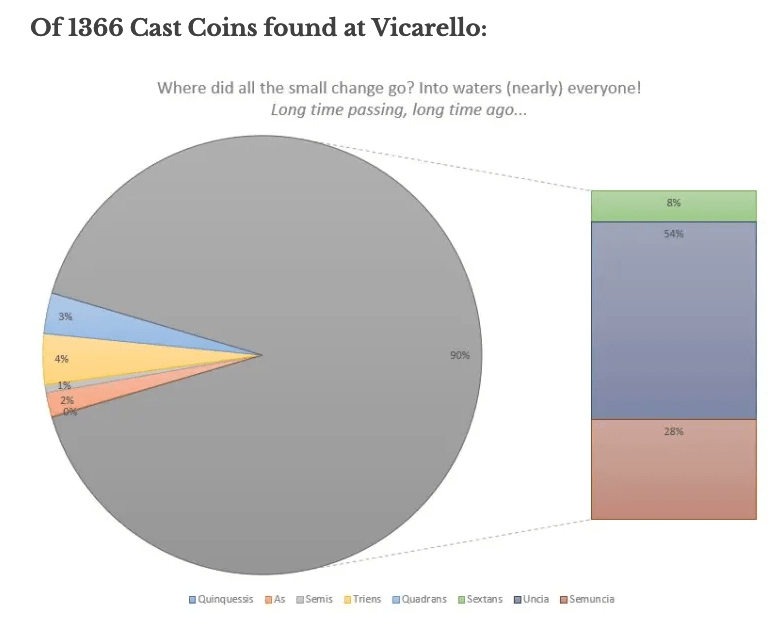

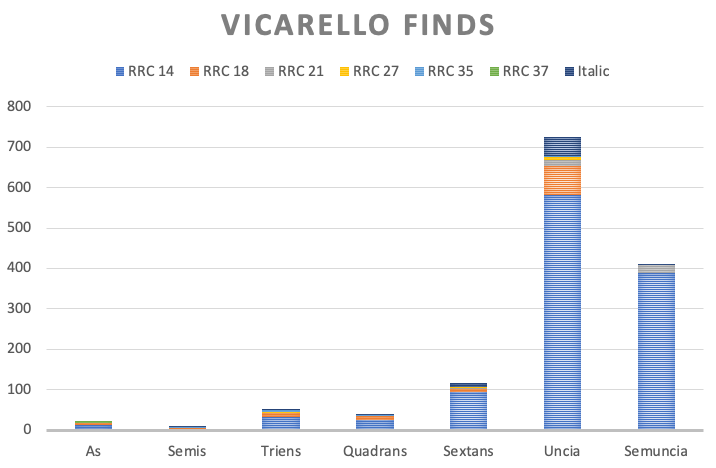

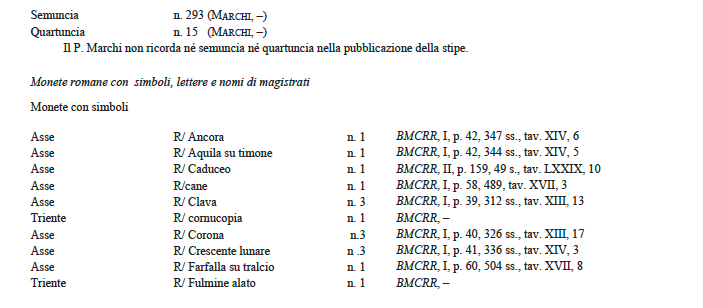

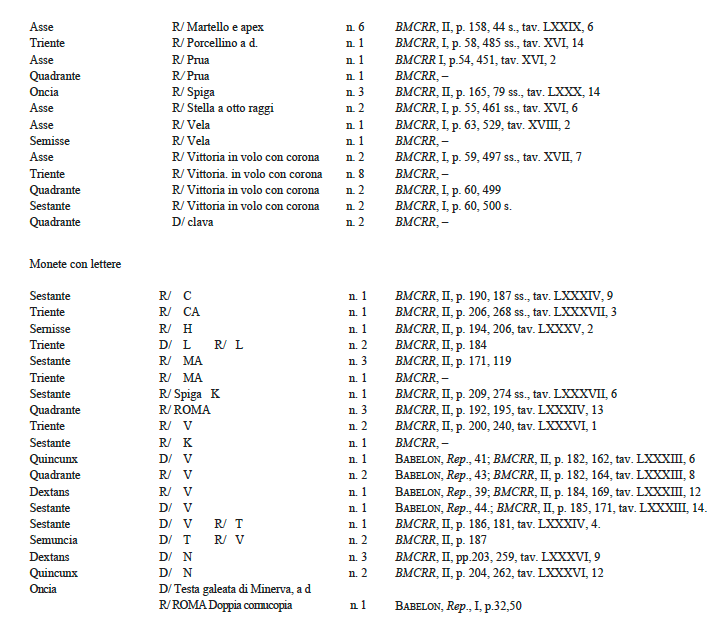

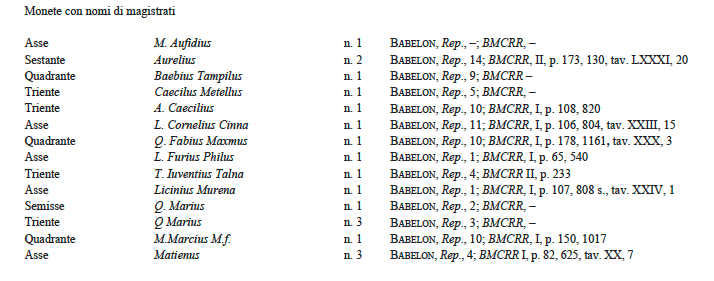

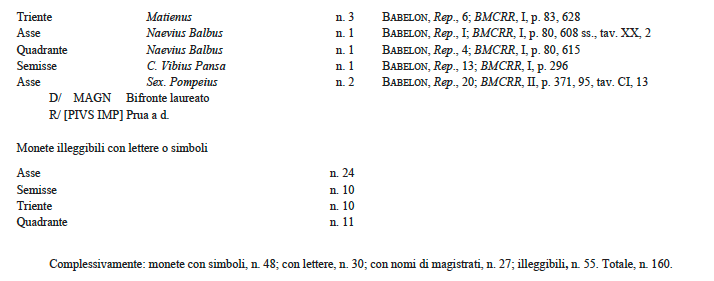

Important for details of signed issues! Also of Italic coins, esp. Etruscan. give not only reported count but also number actually in collection. Here’s taste. V interesting that Marchi failed to record Semuncia and Quartuncia of Prow series.

There is a fanciful reconstruction on display in Palazzo Massimo (or was, gallery has been closed for a long time) to give a sense of scale and possible stratigraphy (the actual stratigraphy summarized but not actually documented).

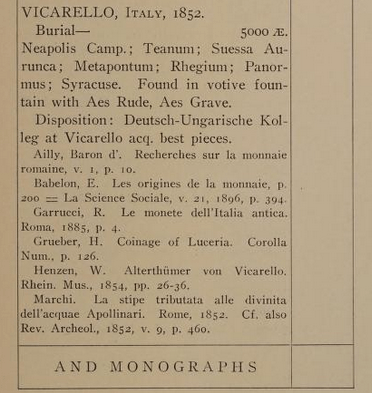

More general bibliography

I’m not listing the cup/itinerary bibliography it is just too long and too unrelated.

Hodges, Richard. “The archaeology of the Vicarello Estate, Lake Bracciano.” Papers of the British School at Rome 63 (1995): 245-249. (Jstor). Survey of previous work and holistic approach to the site, but short.

Falkenstein-Wirth 2011 above

The BM has 4 coins from this votive deposit and one vase; the purchases were made through Rollin & Feuardent, Sambon

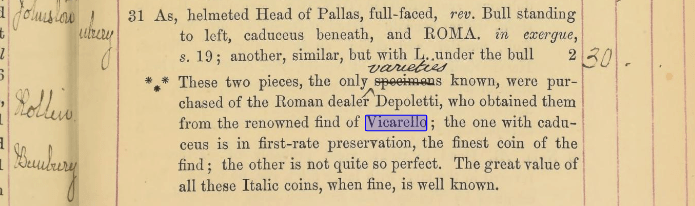

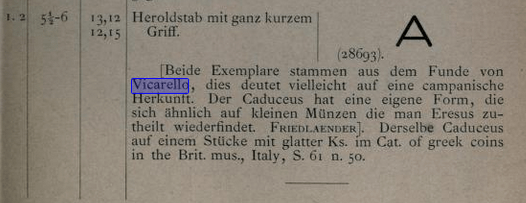

Historia Nummorum Italy 363, second specimen (YET! The Herzen catalogue says only one was found at Vicarello) –

Historia Nummorum Italy 357 (Yet another is listed in Sambon sale 1870 also from Vicarello. But only one is listed by Marchi as found and the BM specimen was sold to them by Sambon in 1870 — I hope no duplication occurred)

RRC 37/1c (Haeberlin illustrates other RRC 37 specimens found at Vicarello)

Again we must ask the question how many Roma/Bull (RRC 37s) were really found at Vicarello. Here is Sambon selling two more with that attribution in 1870. Even after he sold one with this attribution to the BM in 1867. Marchi says 5: 3 cadeuceus, 2 Ls.

BERLIN has 24 pieces of aes rude!

Vecchi 309 = HN Italy 387 (not in Marchi’s find list?!?!)

Most tantalizing:

“uncertain object evenly thick, rounded at the ends, crescent-shaped; roughly like a kidney or bean.”

Here is Garrucci‘s illustration

I wonder if this might be Vecchi 350 = HN Italy 677f?

Noe 1925 says that the best of the Vicarello finds were acquired by the Pontificium Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum de Urbe. I wonder if they still hold them or deposited them with the Vatican? The college has its own library so it is not beyond possibility that they have them still.

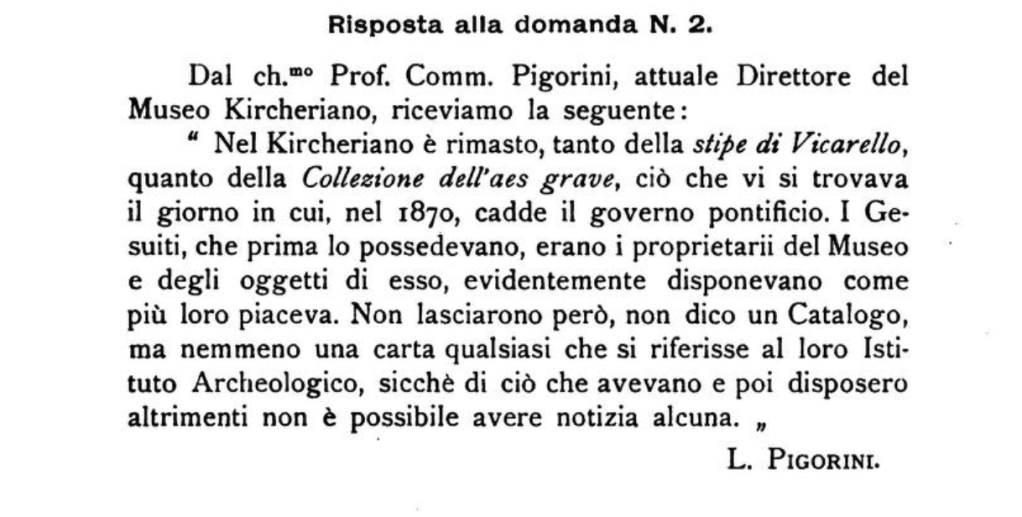

Barhfeldt asked the Italian Numismatics community a series of questions in RIN 1888. one of which was WHAT happened to the Vicarello coins?!

Pigorini director of the Kircher Museum answered in the same publication:

In short he says the Jesuits left not a clue about the what they might have done with the coins either what they chose to keep or what the disposed of in some other way. No papers let alone a catalogue or inventory.