I ponied up the money for wifi on this flight home so I could organize, share, and think more about all the fantastic artifacts I’ve seen. Hopefully if all goes well the next post will be a round-up of the Getty Visit last weekend. I only had 2 hours in this museum so it was rather a speed walk through everything. I’m going to group photos into galleries and/or slide shows. Click on an image to see more detail and uncropped images.

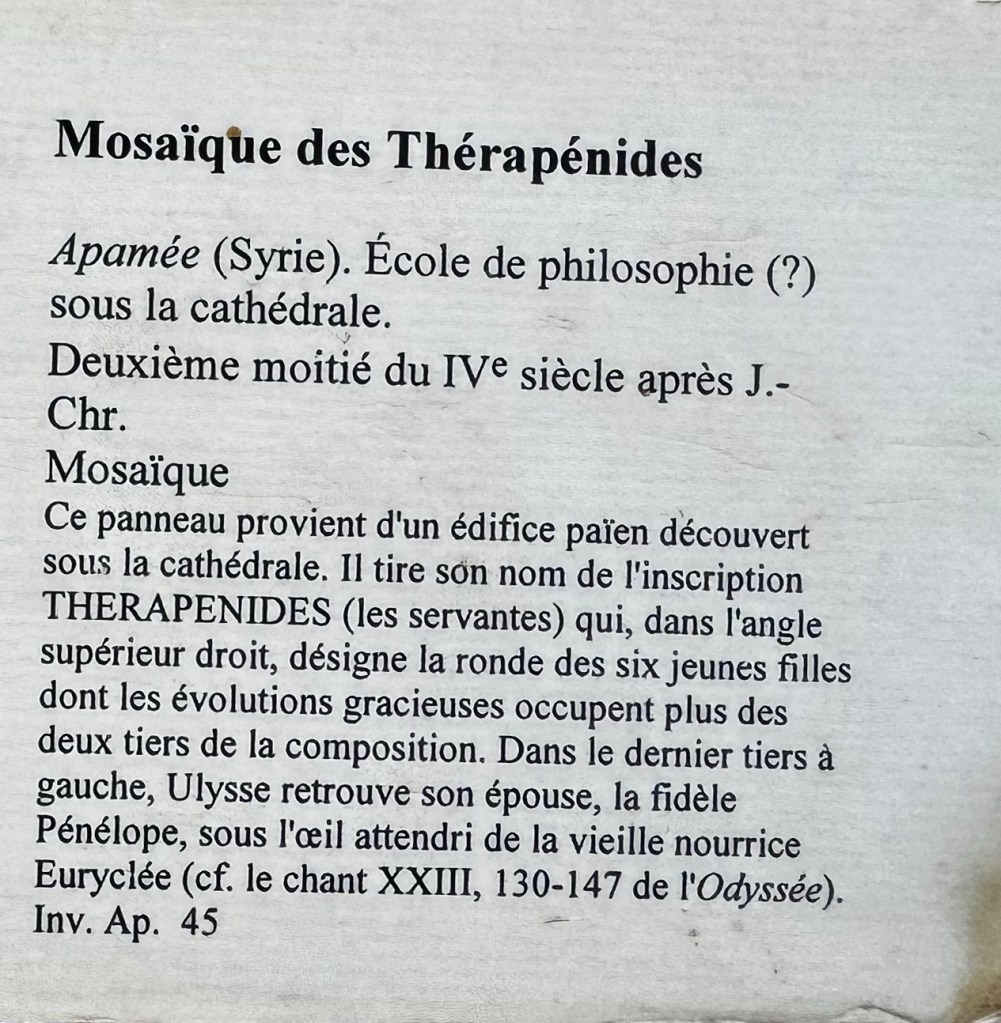

Big Stuff mostly from Apamea, Syria

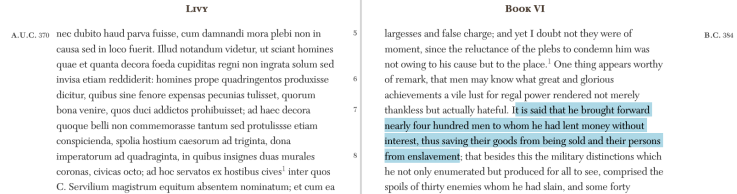

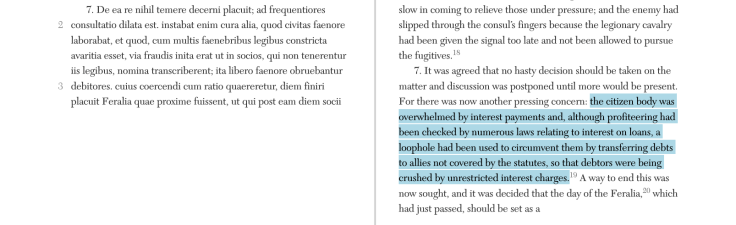

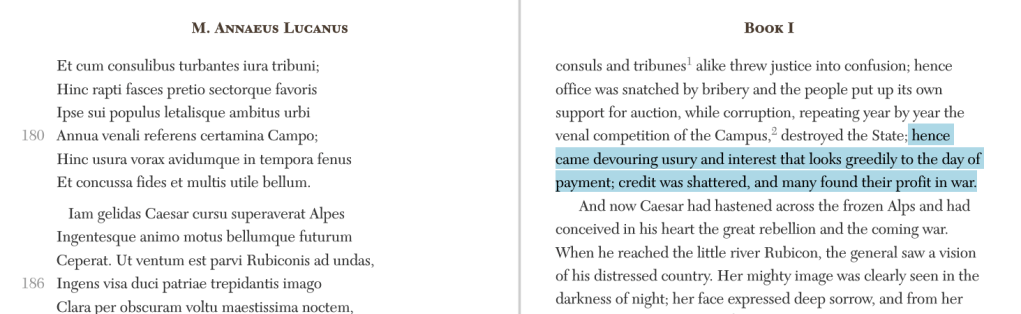

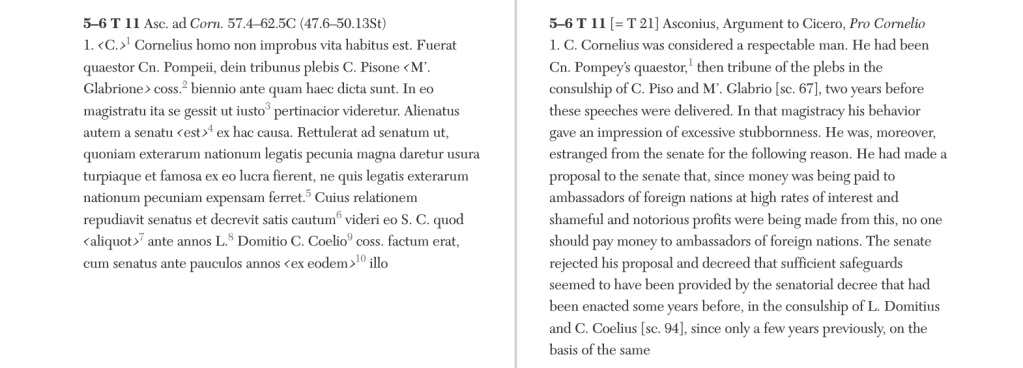

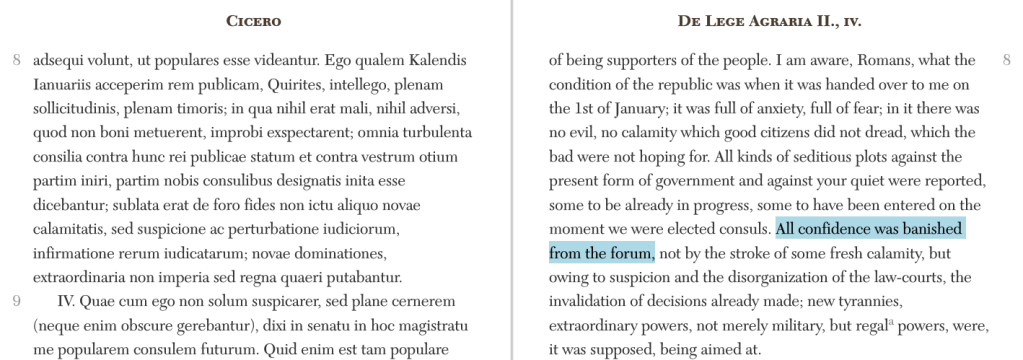

The mosaic of the “Therapenides” (enslaved female domestic workers) commemorates the homecoming of Odysseus and his reunion with the women of his house after the destruction of the suitors. However, the joyous dancing of the enslaved evokes also the murder of the ‘unfaithful’ enslaved women who were gruesomely hung for suffering at the hands of the suitors. The motif of happy dancing slaves especially in this type of ring composition is found through out colonial and imperialist art of the modern period (there are some images in my 2018 tree and sunset article). The kiss at the gate between the reunited enslavers strongly reminds me of iconography of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate, esp. Giotto’s rendering. The munching scene is just one of many from the Synagogue in the museum. The model of Rome is delightful but I did not linger in the interests of time.

Pots

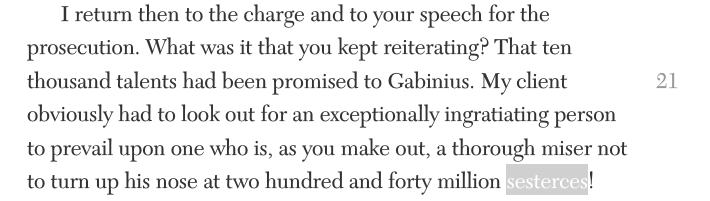

The highlight of this section is the black gloss cup with a relief impression created from a coin of Syracuse with the head of Arethusa. I’ve blogged about this type of cup before but then a different example. The other stamped black gloss pot (vernice nera with petites estampilles) is perhaps more typical of the genre, a fine example, but a poor photo. The askos with the ivy leaves in relief I wanted to remember for comparative iconography. The others are just delightful scenes: women rearrange the furniture, the equipment for stomping grapes to extract the juice and retain the skins and seeds, a polka dot Minotaur, funny stylized sea creatures (=Mycenaean octopus cups). Notice that the shield of the one warrior has a thunderbolt (fulmen) on it. And, the dancers are wearing an early version of the comic fat suit. Less fat, just a little paunch, also a rather small fake phallus. The women dance nude besides a necklace, but notice how their nipples point down in a rather amusing rendering.

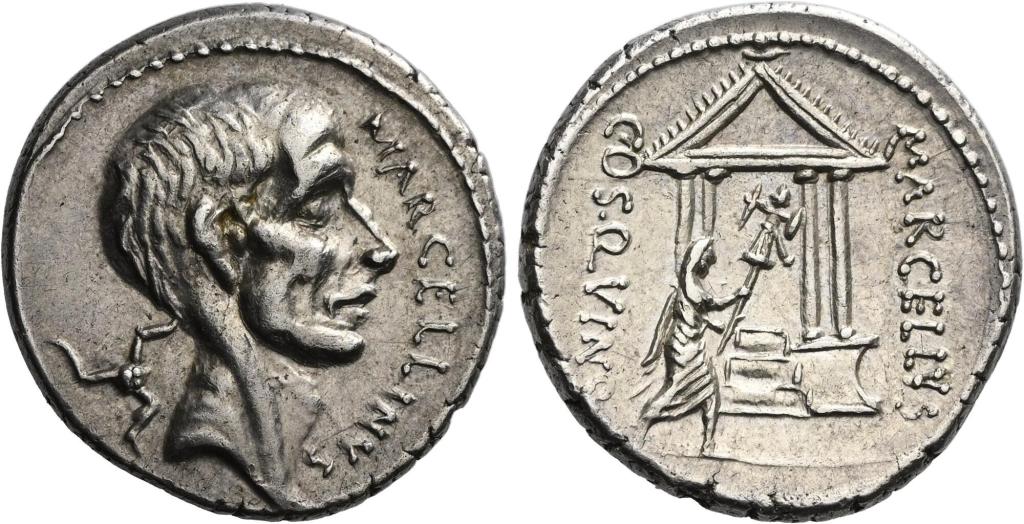

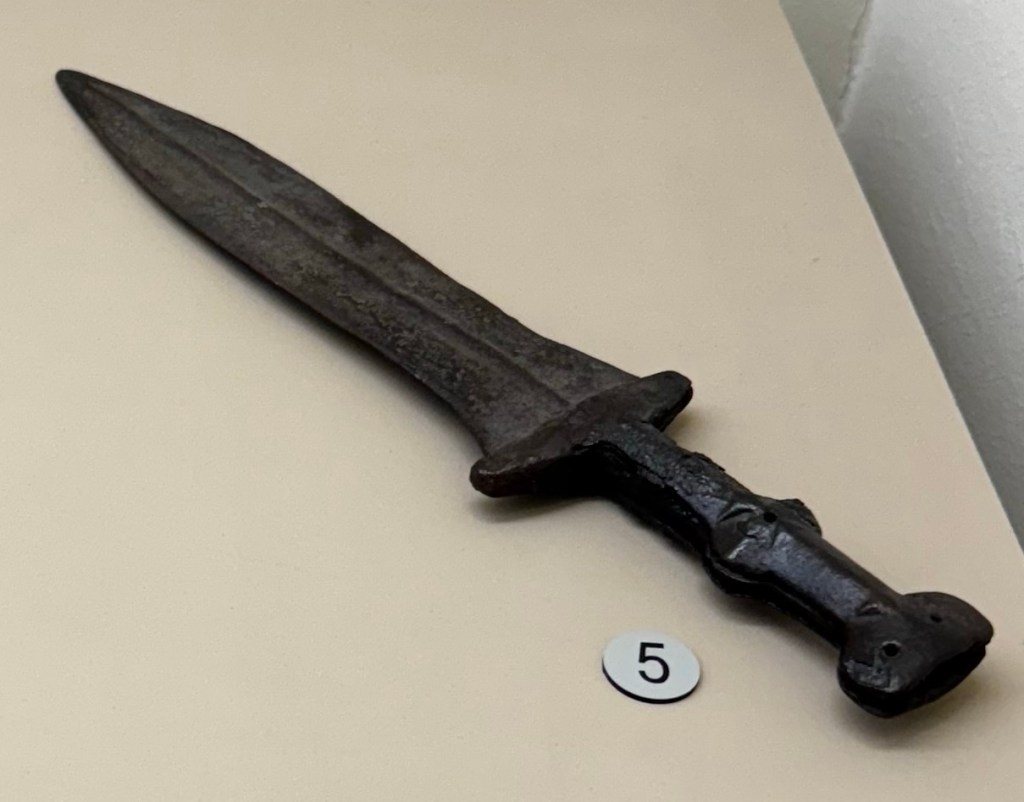

Military stuff

The images don’t do justice to the standard top. It has so many little animal motifs and details worked in to the design that can’t be clearly seen here. The sling bullets (glandes) also have rich decoration AND interesting inscriptions–check out the labels. I thought the detail on the architectural terracotta relief was spectacular–it reminded me straight away of the battle friezes on monument of Aemilius Paulus so well studied by Michael Taylor.

Funerary Stuff

Ever since my 2004 Turkish road trip I’ve been obsessed with the image of two disembodied open hands on grave stele. Somewhere or perhaps lost forever on a fried hard drive I have dozens of images of these symbols from across Anatolia but I rarely meet them in museums outside of Turkey. Lead coffins are rare and this one has some nice sphinxes on it if you look carefully. The sarcophagus represents a lamp stand in use.

Figural terracottas

The color on the Campana plaque with Achilles and Penthesilea caught my eye but also it is just a favorite motif for how it has been adapted artistic representations of conquest in Roman art (a theme of past blog posts). There Hercules and boxers relief is a nice study in idealized hyper masculinity. Cybele’s lap cat is hilarious so needed a photo. The lamps provide examples of how it is not only disability that interests ancient artists exploring the extremes of the human body, but also how hard labor especially for the enslaved leads to disfiguration. The squatting woman I think is obese or has an abdominal tumor rather than being pregnant. The face seems older and the cup suggests a life of over indulging in wine. Perhaps a variation on the drunken woman clutching a vase.

Other objects of interest

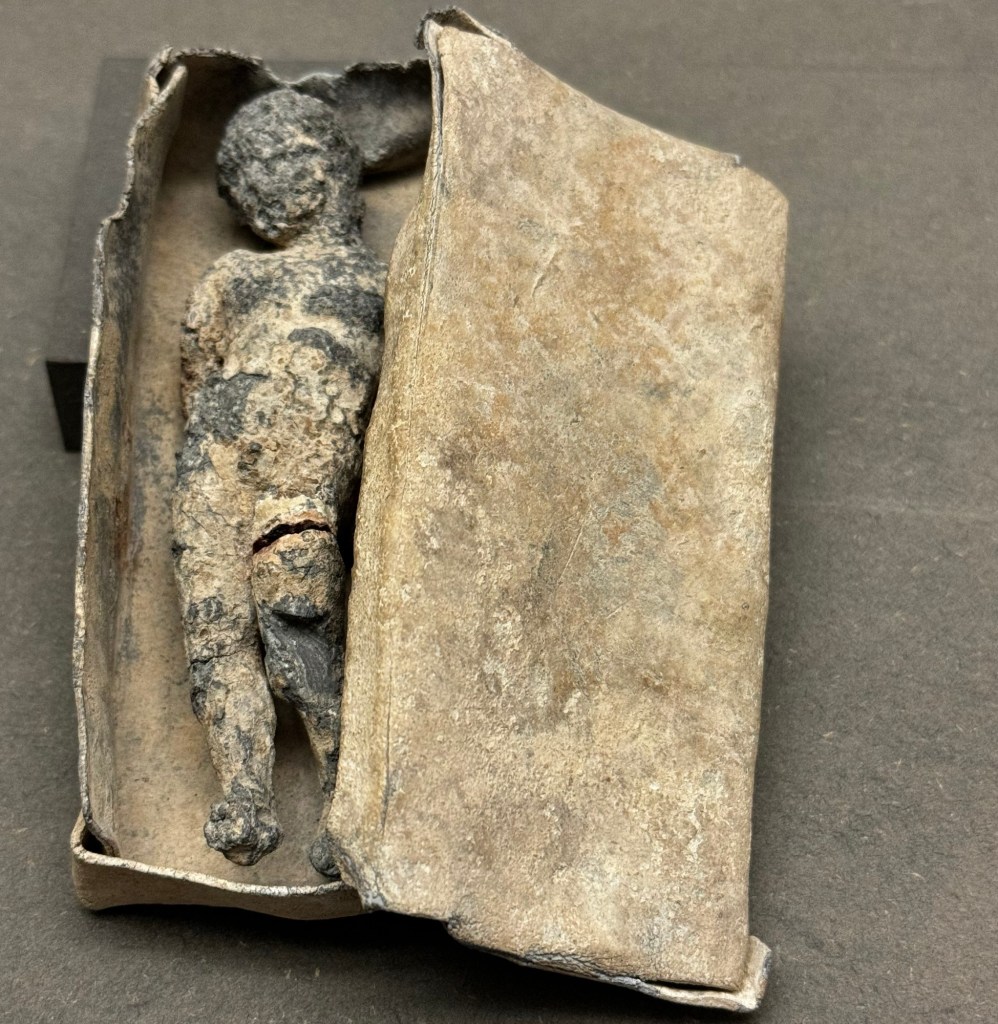

The water spigot with the disturbingly distorted head of a black person didn’t have a label. For context I also photographed a lamp in the form of a similarly distorted head. What is up with the abuse of the mouth!? The snail shell is another bronze lamp. A fully intact wooden table from Luxor is certainly noteworthy. It has a similar share to tables depicted in some Pompeian frescoes. The lead figure in a lead box (coffin?) is almost certainly a magic object related to cursing, but it also lacked a label. The thumb is carved from bone in exquisite detail and was the handle of a knife: it and the cameo and spindle, lantern, and glass objects were all from Belgian finds, mostly tomb assemblages. The wax tablet was photographed because of the figural complexity of the scraper, the blade of which was either v smooth glass or rock crystal. I failed to make a note if the materials were listed in its label.