One of my fondest archival memories is reading letters sent to Hersh by scholars across the globe and inferring a bit of what he might have said to spark the response. I flatter myself that today’s fast paced online world creates something of the same scholarly exchange below the level of publication. A sharing of ideas, a willingness to be wrong and learn from our peers. I blog to capture my stray thoughts for myself to figure out what I might think, but the best is when others write back and help me learn more. Andrea Pancotti sent me his 2013 essay and I’m beyond grateful. I’m flying to the AIA (SCS) and have completed one student reference, one professional reference, and made it through another Wiseman chapter. More chapters and references need attention this flight but I wanted to return to Cetegus and honor Pancotti’s generosity.

Let us start with some important factual information.

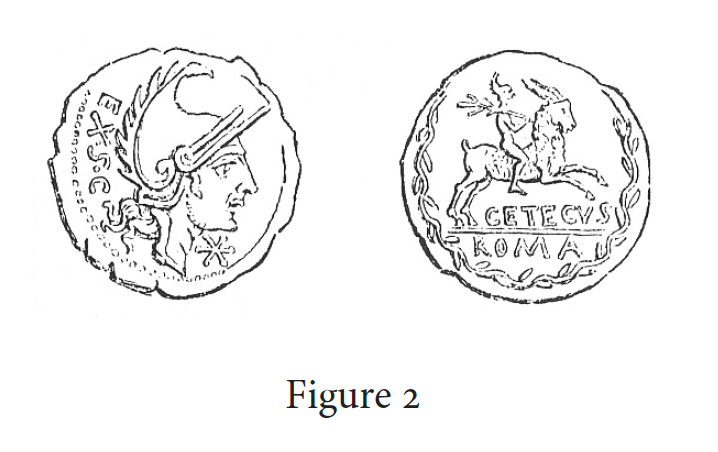

“Only one example of this denarius is officially known today, preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (Ancient Fonds 1068). In the second half of the 19th century, a second example was reported in the numismatic cabinet of the ducal palace of Gotha in Thuringia (BAHRFELDT 1897, Cornelia 5, p. 91): this one, whose authenticity was seriously doubted (M. Bahrfeldt in NSA 1876, 2 [February], pp. 9 and 19; ENGEL 1879, p. 34, n. 1), presented small details on the reverse (such as the shape of the goat’s beard) that stylistically differentiated it from the coin preserved in Paris. After World War II, the collection suffered considerable losses, and the piece is currently missing.” (p. 279 n. 2, roughly translated)

This is a good reminder of the fragility of the historical record. I also find his comments on how preservation effects interpretation very apt and important”

“Given the state of preservation of the specimen preserved in Paris (bb-VF), it is not possible to determine with certainty the floral elements that characterize the wreath; for Eckhel (ECKHEL 1795, p. 180), Cavedoni (CAVEDONI 1829, no. 46, p. 152), Riccio (RICCIO 1843, no. 15, p. 63), Cohen (COHEN 1857, p. 101) and Crawford it would be ivy; for Babelon and Belloni it would be laurel (BELLONI 1960, p. 73, no. 539); according to a further interpretation by Cavedoni, it would be “two branches laden with leaves or oblong fruits”. (p. 280, n. 4, roughly translated)

In 2013 Gallica and its high resolution images were not available. Today we can all have an opinion on these fine details worn and indistinct as they may be.

I’m pretty confident that laurel can be ruled right out. Laurel wreath borders pretty universally on coinage look different, more like as series of interlocking Vs starting at bottom and center and going up both sides (e.g. RRC 263/1 and many more besides). There are no ivy borders on the republican series for comparison. The most famous ivy border of the hellenistic period is that of the cistophori, but these wreaths (example) tend to alternated two leaves and berries clusters and/or flowers. The heart shape of the leaf is typically emphasized. What I see is a wavy line with alternating small leaves. It is hard to make this out to be ivy. The motif feels distinctive and possibly can be matched to other iconography in future. The drawing of the now lost second specimen shows the border slightly better (if it is accurately rendered and if the coin itself is genuine):

“Before the excavations conducted at the end of the last century at the sanctuary on the Palatine Hill, which uncovered numerous votive offerings dedicated to Attis dating back to the 2nd century BC, the deeply rooted belief among scholars that the cult of the Phrygian god only spread widely from the imperial period onwards was always stronger than a critical analysis of the primary sources, even in the face of the evidence of the key role of M. Cornelius Cethegus, an ancestor of the moneyer, who held the consulship with P. Sempronius Tuditanus in 204 BC, the year of the official introduction of the cult of Cybele in Rome.” (from page 281)

This is absolutely key.

I’m now skipping over any mention of his excellent re reading of RRC 353 to which I may wish to return at another point in detail and discuss just a bit below.

I browsed Attis in LIMC to make up my own mind if this was iconographically possible. I’d normally drop in a bunch of screen shots here but the wifi on this plane just isn’t up to that. The most distinctive and consistent part of his iconography is his youth, often, pudgy, with a Phrygian cap and and funny trousers. All of these could correspond to the coin. The funny trousers cannot be confirmed given the worn surface of our one extant specimen. There are a variety of attributes he holds in other depictions. Most common are the pedum and pan pipes, marking him as a shepherd god. But plenty of other attributes are shown (theater masks, cornucopiae, torches, even a small round shield). In two images, nos. 142 and 143, he is shown like the good shepherd with a sheep or goat on his shoulders, which type of animal is unclear, at least to me (cf. also 214). No. 146 has a small shepherd milking a goat at Attis’ feet. No. 236 is an adorable figurine of baby Attis cuddling either lambs or kids. Nos. 291, 293-295 show Attis sitting side saddle on a giant rooster. Not an exact parallel but a nice indication that Attis does ride animals, as Erotes often do. Attis has other parallels with Erotes in his iconography, sometimes leaning on an extinguished torch (like Thanatos) and even commonly winged and depicted as such in jewellery. Nos. 297-298 has him riding a lion (attribute of Cybele). And most intriguing is no. 304b which is a figure that is meant to be astride an animal that is now missing.

I was despairing about the little spikes on the Phyrgian hat on the coin as I’d seen nothing parallel in LIMC until I got to no 312 which clearly has rays coming from Attis’ hat. From the front not the ridge but still I’ll take the parallel. Compare this figurine from Tarsus in the Louvre.

I am also a little befuddled by the branch on the coin. Attis never holds one, that I’ve seen thus far, even if many of the reliefs and 2D scenes include a tree. I think here no. 335 may help. It is a relief of symbolic cult objects including a bust of Attis. Above the bust is a tree/branch with ritual objects dangling from it. Perhaps this is suggestive that such branches or trees were closely associated with the cult, not just pastoral scene setting in the other reliefs.

I now understand why Grueber wanted to date this coin to 104 BCE, the year of the embassy from Pessinus that caused such a stir. See Diodorus 36.13.

So I’ve come to agree that Attis seems most likely, but we’ll need further explanation of the branch I think at some point.

Pancotti suggests that RRC 353 may refer indirectly to the cult of Attis, alongside other gods, in a response to contemporary politics. I find his logic very interesting, even compelling, but will let you make up your own mind whether you are convinced. The type of symbolic enmeshment he sees in the design does have other instances on the republican coin series. I’ve mentioned this only briefly on the blog with regard to RRC 409/1, but it also applies to RRC 352/1. The latter especially lends weight to Pancotti’s argument. In many ways, what we make of RRC 353 is a much more important historical question than what we do with the Cetegus coin type.

I leave you with a little more Pancotti:

“It is not surprising that Attis was not depicted directly [on RRC 353], as in the coin of the Cornelia gens: presumably, the extreme rarity of the Cethegus denarius is due precisely to the direct depiction of the god, in contrast to the political line pursued by the Roman Senate towards the orgiastic rites in his honor; this must have led to the minting of the coin in a limited number of specimens or, more likely, its sudden withdrawal from circulation.” (p. 283-284, rough translation)

Speculation, yes, but certainly highly plausible!

Update 1/13/26:

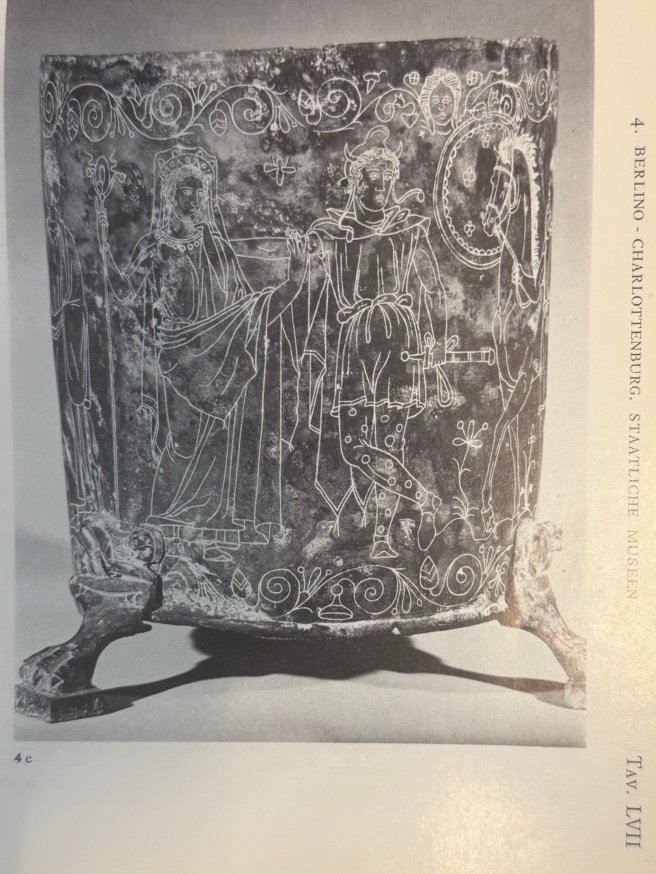

Excavated in 1870 formerly in Rome now in Berlin. The catalogue by Bordenache Battaglia of 1979 dismisses that this could be Attis and Cybele because he does not believe these the former would be known in Rome at this date early date. I can see nothing but Attis.

Note to self, the next time I discuss the Veovis/Apollo types, I must review:

L. PEDRONI, Crisi finanziaria e monetazione durante la guerra sociale, (Collection Latomus 297), Bruxelles 2006. p. 133-145

[old post where Pedroni should have been discussed – I’ve got a roughed out chapter on this for my next book as well, but it needs much work before publication]