Just throwing this up for ease of future reference:

Taken from Turfa’s book.

Here’s Santagelo on the prophecy and it’s likely historical context.

adventures in my head

Just throwing this up for ease of future reference:

Taken from Turfa’s book.

Here’s Santagelo on the prophecy and it’s likely historical context.

The auction catalogue of this specimen linked this type of Sulla’s with Vibo Valentia. An interesting idea not in Crawford (“275 – Q Mint-uncertain 81 BC”). Here’s the CRRO link for 375/2 (375/1 is the same type in gold).

Where did the idea come from? Clearly it is inspired by the iconographic similarities of the Semis type of the colony (HN 2263):

I picked a specimen that makes the visual parallels most evident. The styles vary considerably over the years; see this acsearch.info set of results for a quick demonstration of this stylistic variety.

I traced the idea back to Bahrfeldt via Alföldi but it may go back further.

Is it plausible? Maybe. None of the hoards containing this type come from Southern Italy, but that isn’t definitive by any means:

Didn’t know a collection of Alföldi’s papers were translated into English? Me neither until today! Here’s the Table of Contents.

Note to future self: I also really want to think more about what it means that the carnyx is used as a mint mark at this colony…

So I’m trying to wrap my head around the possibility that the ludi Apollinares were introduced because of a connection between Apollo and Tarentum (cf. Livy 25.1-12). This idea seems accepted by Santangelo on the basis of Russo 2005. I really admire the work of the former so want to go along with it, but I am trying connect the dots as it were. Russo led me back to Evans (yup, good ol’ Sir Arthur):

This article is free on JSTOR (see p. 190-191). Anyway. This got me worried we’re in circular logic territory. Evans is using Republican imagery to argue an Apollo connection back onto the Tarentine evidence (maybe correctly?) and then Russo is pulling that forward to support our interpretation of Apollo’s significance in Rome in 212 BC. Bah. So what about Evans’ suggestion that the Roman desultor imagery derives from Tarentum? He doesn’t tell us which coin he means so I’ve had to guess. This one has two horses and one rider so is perhaps what he means.

Two horses yes, but no whip, no felt hat, etc etc. Not a great parallel.

Here are my older posts on desultores. (Notice the coin of Suessa has Apollo on the obverse!)

I actually think the strongest evidence for why horse races are part of the ludi Apollinares may actually come from Tacitus as cited by Russo, but has nothing to do with Tarentum!

Here’s Tacitus 14.21:

“Our ancestors,” they said, “were not averse to the attractions of shows on a scale suited to the wealth of their day, and so they introduced actors from the Etruscans and horse-races from Thurii.

The critical point here is that in 212 BC Hannibal had not only taken Tarentum but also Thurii! (see Livy link at top of the post.)

Some young Romans turned their training in the Circus games to purposes of war and in this way seized the lowest portion of the wall. Before the extravagant habit came in of filling the Circus with animals from all parts of the world, it was the practice to devise various forms of amusement, as the chariot and horse races were over within the hour. Amongst other exhibitions, bodies of youths, numbering generally about sixty, but larger in the more elaborate games, were introduced fully armed. To some extent they represented the maneuvers of an army, but their movements were more skilful and resembled more nearly the combat of gladiators. After going through various evolutions, they formed a solid square with their shields held over their heads, touching one another; those in the front rank standing erect; those in the second slightly stooping; those in the third and fourth bending lower and lower; whilst those in the rear rank rested on their knees. In this way they formed a testudo, which sloped like the roof of a house. From a distance of fifty feet two fully armed men ran forward and, pretending to threaten one another, went from the lowest to the highest part of the testudo over the closely locked shields; at one moment assuming an attitude of defiance on the very edge, and then rushing at one another in the middle of it just as though they were jumping about on solid ground.

A testudo formed in this way was brought up against the lowest part of the wall. When the soldiers who were mounted on it came close up to the wall they were at the same height as the defenders, and when these were driven off, the soldiers of two companies climbed over into the city. The only difference was that the front rank and the files did not raise their shields above their heads for fear of exposing themselves; they held them in front as in battle. Thus they were not hit by the missiles from the walls, and those which were hurled on the testudo rolled off harmlessly to the ground like a shower of rain from the roof of a house.

I don’t really think I believe it originated in the Circus and then was applied on the battlefield, but it certainly was a memorable, showy move!

Visual aid from Trajan’s column:

To add to the confusion the sound of a trumpet was heard from the theatre. It was a Roman trumpet which the conspirators had procured for the purpose, and being blown by a Greek who did not know how to use it, no one could make out who gave the signal or for whom it was intended.

I’d like to read up one day on the use of musical instruments in warfare and variations among different ancient peoples. And I just find this bit of Livy (25.10) describing Hannibal’s taking of Tarentum rather amusing.

The natives near the pass conspired together and came out to meet him with treacherous intentions, holding olive-branches and wreaths, which nearly all the barbarians use as tokens of friendship, just as we Greeks use the herald’s staff.

Earlier posts discussing this symbolism.

Not sure if I put this up here before but the best real caduceus I’ve ever seen is in the Minneapolis Institute of Art:

I’ve previously blogged about the falcata (Spanish sword) as an ethic marker on republican coins. Thus I found this passage of interest (Livy 31.34):

Philip’s men had been accustomed to fighting with Greeks and Illyrians and had only seen wounds inflicted by javelins and arrows and in rare instances by lances. But when they saw bodies dismembered with the Spanish sword, arms cut off from the shoulder, heads struck off from the trunk, bowels exposed and other horrible wounds, they recognised the style of weapon and the kind of man against whom they had to fight, and a shudder of horror ran through the ranks.

nam qui hastis sagittisque et rara lanceis facta uolnera uidissent, cum Graecis Illyriisque pugnare adsueti, postquam gladio Hispaniensi detruncata corpora bracchiis cum humero abscisis aut tota ceruice desecta diuisa a corpore capita patentiaque uiscera et foeditatem aliam uolnerum uiderunt, aduersus quae tela quosque uiros pugnandum foret pauidi uolgo cernebant.

There are actually a number of passages in Latin that discuss Spanish swords.

And Euphorion the Chalcidian, in his Historical Memorials, writes as follows – “But among the Romans it is common for five minae to be offered to any one who chooses to take it, to allow his head to be cut off with an axe, so that his heirs might receive the reward: and very often many have returned their names as willing, so that there has been a regular contest between them as to who had the best right to be beaten to death.”

from Athenaeus.

Or perhaps just an othering of the barbaric Romans.

Here’s Galinsky in Augustan Culture thinking about this coin type and other related republican types as they may have informed Augustus’ own use of Numa.

Cf. Farney’s thoughts on this type.

These examples were all plucked off acsearch.info and are thus from auction catalogues. They just supplement the many images available on CRRO for RRC 319/1. Anyway I just want to note that the right hand figure, which Crawford identifies as a barbarian soldier is probably meant to be a Macedonian. The round shield is one hint. As are the horns on the helmet, this may even mean a royal Macedonian is meant (see earlier posts). I think the strong diagonal element across the figure’s chest may be trying to represent a chlamys (Macedonian cloak).

Cf. Alexander’s chlamys on the so called Alexander Sarcophagus

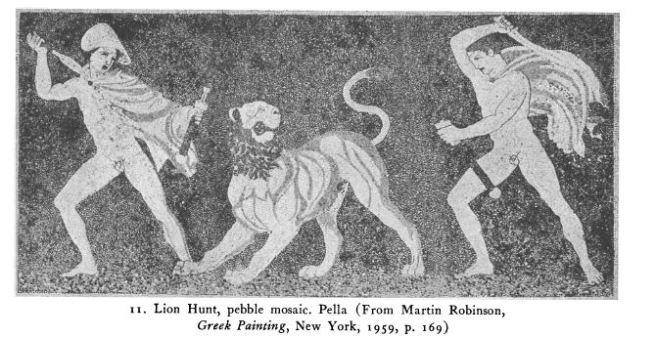

And the left hand figure’s chlamys in this Pella pebble mosaic: