This deck contains slides used in all four talks but is not the precise deck used in anyone version.

If you follow me on social media you know that I had quite the odyssey to get to McMaster because while I am something of a Diva, I can’t compete with the Diva queen who performed in Toronto last night clogging every airport, rental car counter, and highway between NYC and points north. I made it by re-routing through Buffalo and renting a electric Kia Niro (strongly recommend) in a lovely shade of green. Yesterday’s heart-pounding stream of rebookings were made up for by the gorgeous venue, mouthwatering dinner, lively conversation and falling into a truly lux hotel bed.

So after minor struggles with chargers in the rain (gas stations sorted this back in the 1950s or earlier clearly we can do better!), I’m in a great mood at the Buffalo airport and thinking about the future of this paper over a plate of wings and a bloody maria (tequila, because vodka is boring).

I said as I presented this talk that this was its last outing. 4 times feels like the end of the road for any research topic. I’ve in the past resisted any repeats for research talks. But, in this model where I don’t script, just talk, the multiple instantiations have helped me figure out what the hell I’m talking about. Is there a there there?

I think in the end the answer is yes. It’s just in answering my research questions and returning to old projects, I find I can finally articulate why this material interests me and what the real gut level question has been all along.

DOES MONEY MATTER?

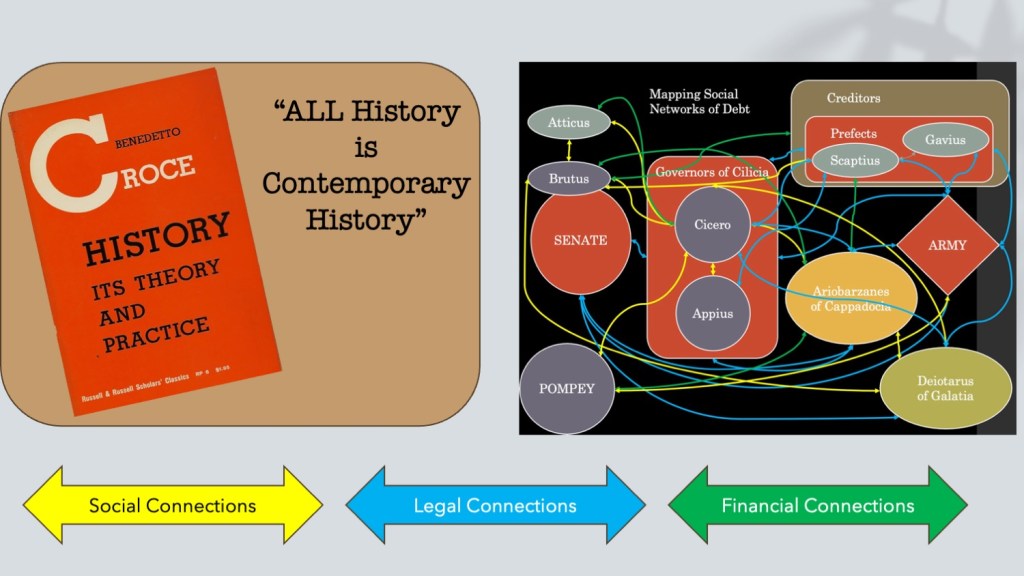

Let’s narrow that down a bit. Is money a factor in political shifts? And if so, how and why? Can we separate out economic factors from politic and can we disentangle which drives which? This was the first time presenting this paper post election (no I don’t want to go there, but I insist on being radically honest about influences on my thinking past and present).

[I’ve switched to a virgin mary, no I don’t really write while drinking even this kind of mind dump research journalling.]

So I started from a desire to ask: are economics or social factors driving politics?

Then I moved to wondering more if the right question was between economics driving politics or politics driving economics or at least economic anxieties. For a while I wanted to know if this was even a question like the dichotomy of the first question. Can’t we just throw our hands up like good Episco-peeps disputing the nature of communion and declare a both/and paradox where we must seek to trace the via media, the middle way.

[ten minutes until boarding]

And yet I don’t think any of this is really the issue. I don’t believe a significant economic or monetary crisis contributed in the slightest to the conditions that allowed Caesar to cross the Rubicon and change Rome forever ever more.

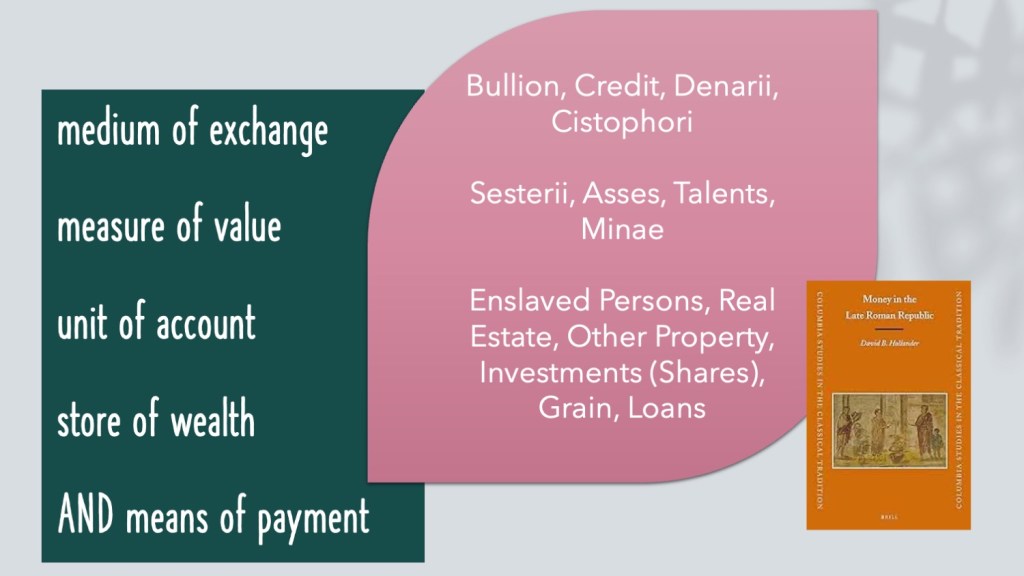

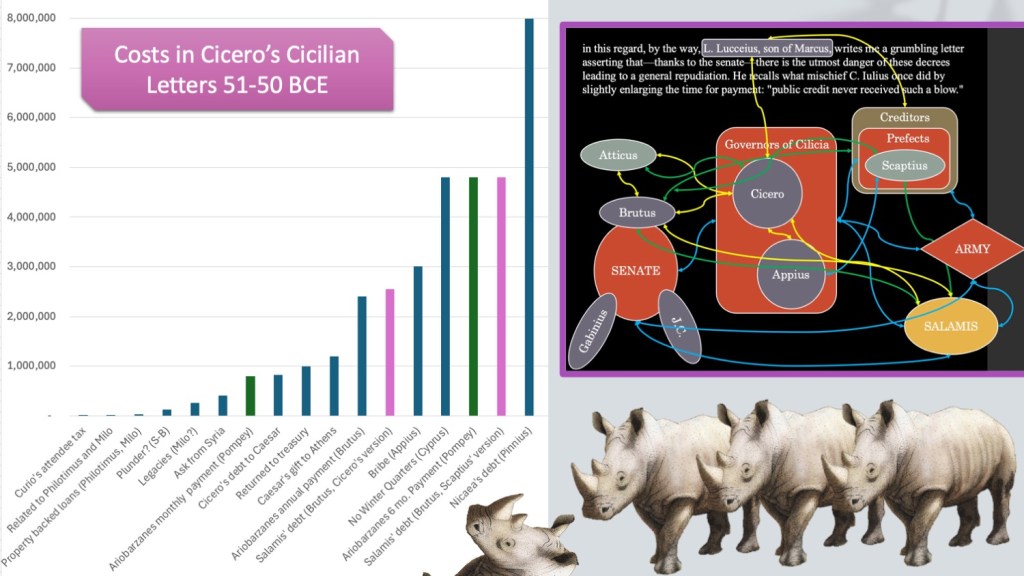

Yes, property was overvalued in the city of Rome in the 20 years before.

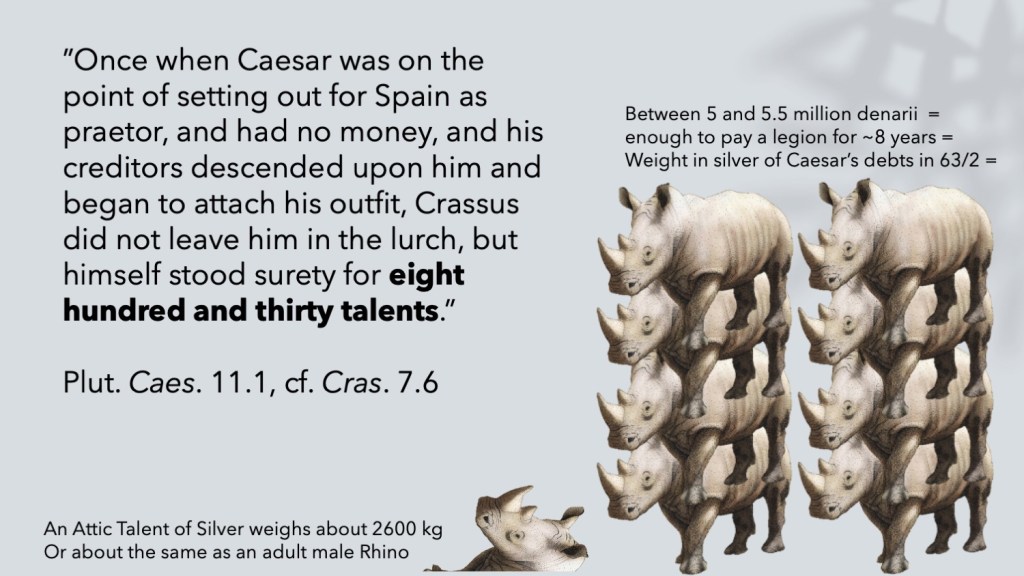

Yes, Rome had a sophisticated system of credit and interest rates were determined by the relationships of borrower and creditor, meaning that interest and payment schedules fluctuated in an unpredictable manner.

Yes, Rome was deeply committed to extracting wealth from the wider Mediterranean and yes there was the a deep entanglement of taxation of and private lending to communities and individuals.

Yes, war and social unrest created widespread economic anxiety and true hardships for some.

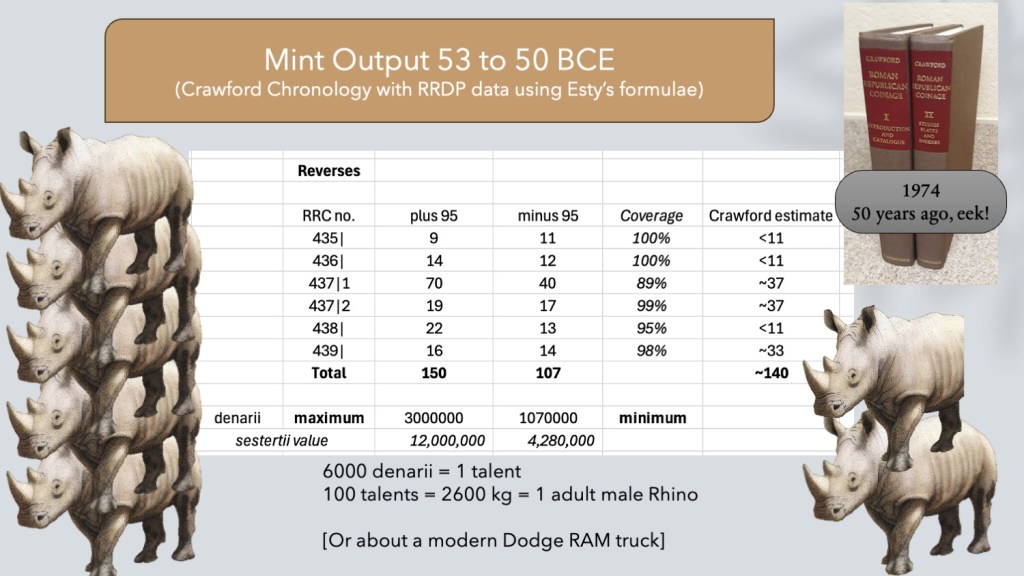

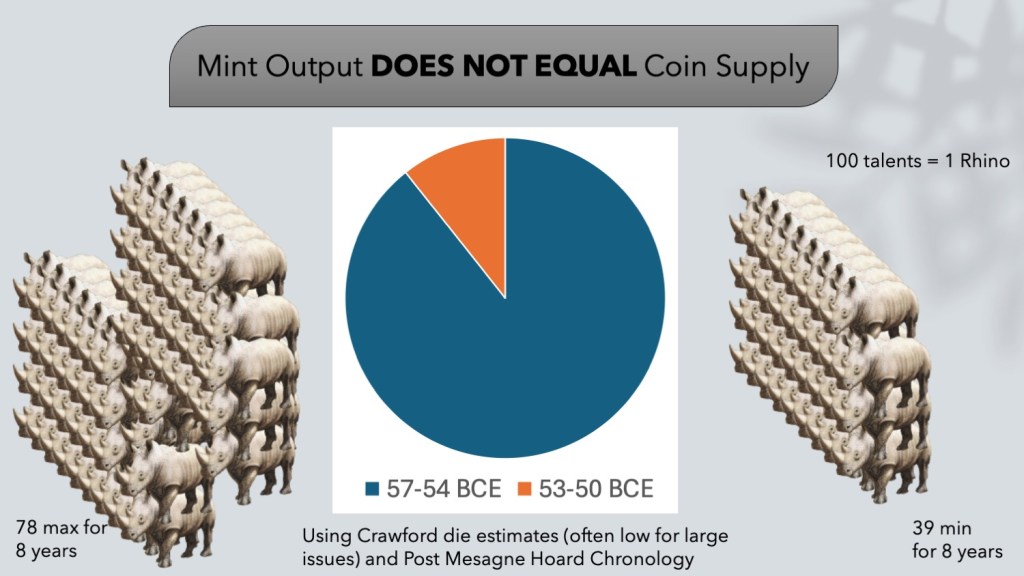

Yes, the Roman mint was not striking sufficient small change for the general population and ridiculously curtailed mint out put of silver in the four years before Caesar’s crossing. This is best explained by a surplus of struck coin and plenty of silver reserves in the state treasury.

No one voted Pompey or Crassus or Caesar in because of the cost of milk, bread, and gas.

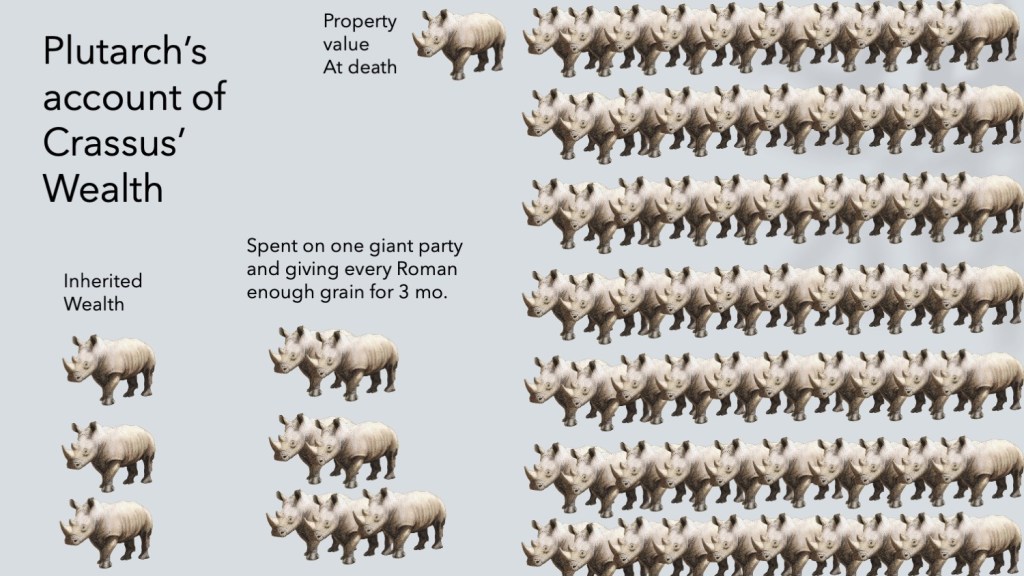

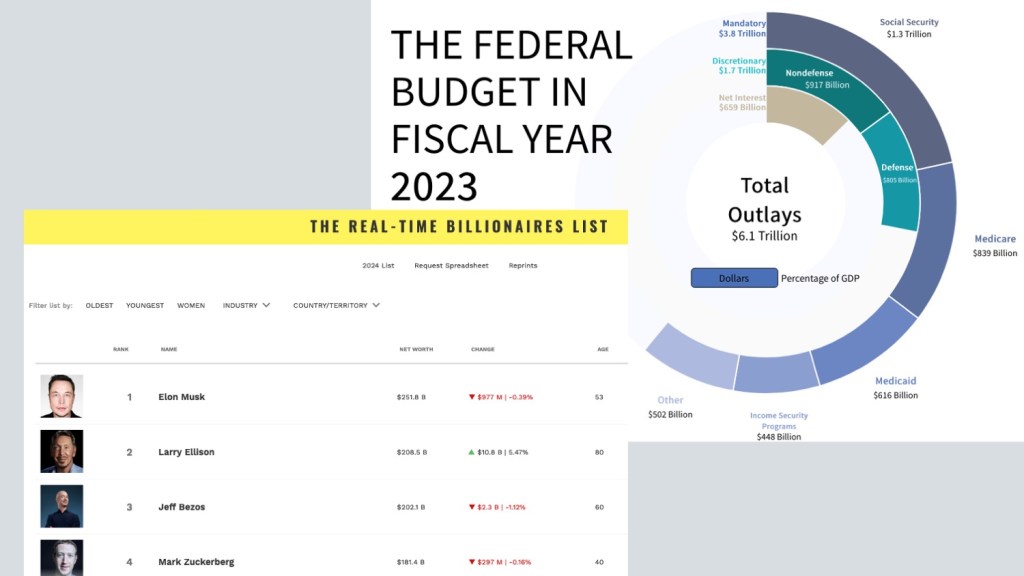

So does money matter? Yes, I think it does, but I THINK it matters because of the economic differential between the state and the wealthiest individuals.

Rome was and remained wealthier than any one of the ultra wealthy, but private individuals could and did spend money of public affairs to rival the state. This ability to spend, this wealth hoarding, could and did destabilize the Roman state.

And, with some relief I can tell you that at present our own modern day ultra wealthy cannot spend anywhere near the spending of the major world governments. And therein is the difference between my modern contemporary anxieties and my cool headed reading of the ancient evidence. There is no one on this planet who is as rich as Crassus at least in comparison of spending power to the government.

Crassus shows that money was not enough. Leadership mattered. Talent and acumen count for a great deal. And, yet I think I might be able to defend a position that argues the economic crisis of the 50s (if we can call it such) was the demonstration that individuals could and would spend more on public affairs than the state itself, thus usurping state prerogatives and eventually destabilizing the very constitution.

I need to go board, but this is a first stab at expressing some of the ideas that evidence of this paper might reasonable support in a fuller formal version.