If you are not familiar with the concept of “sitzfleisch” the BBC will explain it to you.

Warning. This post starts as me trying to figure out what to work on and then swerves very heavy into the question of myth formation and if we can create historical timeline of the creation of mythic narrative. It is a very long post.

Yesterday I was mostly a petty bureaucrat, necessary and productive, but my work had a whiff of the inappropriate about it. I’m in my office in a research library. Research should be the priority. And yet, with the holidays and conference I certainly needed my Plough Monday to dig through the most critical of emails.

But what research?

Do I continue with the AVREVS volume? Probably a practical choice. That would mean returning to the posts I made last November and just continuing the series.

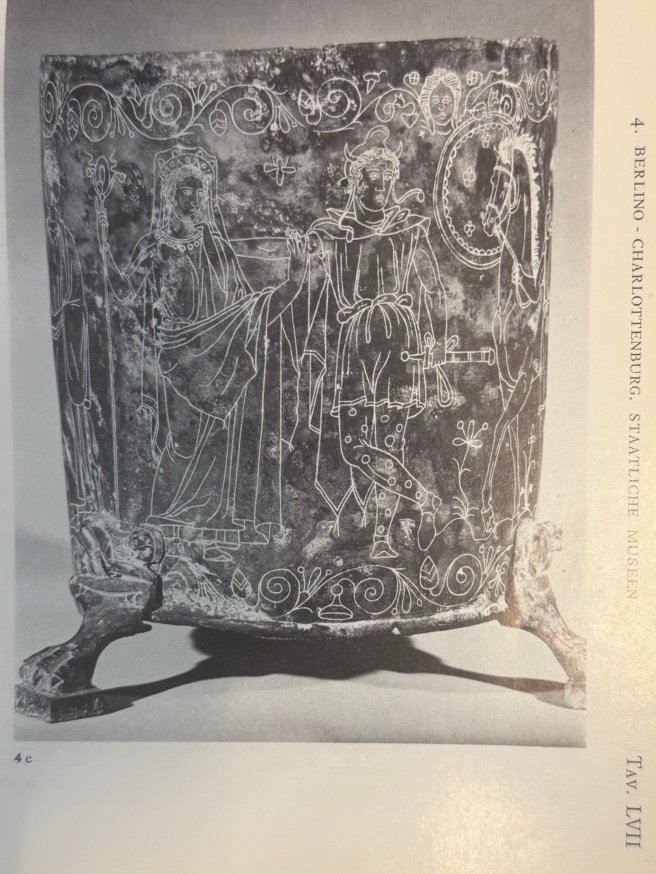

I could continue my relationship with the Wiseman volume for Monday’s event. I’m making steady progress, however, in the off moments out of the library. His views of on Bradley were kinder than on most but he still had a go at his framing of Myth. [I tackled chapter 14 over a pint after work last night in really classic English pub–what a joy!]. Perhaps it doesn’t need library time, my best hours. Unless I want to actually say something about the Bolsena mirror. What would I say? I think what I would want to tackle is the idea that even if it contains a reference to the lares (which is certainly plausible) how can that exclude the existence of a Romulus and Remus interpretation of the mirror itself or the very existence of some version of the narrative?

I’m a both/and thinker, and tend to reject either/or approaches. Reality is complex and I don’t necessarily think two apparently opposing views require one to be wrong and the other true. They may be parts of an elusive whole of which we are only seeing fragments. Or frankly, they may both be wrong. Certitude is the greater sin.

Theatre and story tellers can craft narratives that become legend, most certainly. The most powerful retellings become canonical and can be retrojected onto deep time. And yet, narrative is iterative especially when narrative defines a community and a shared experience. The acceptance of a narrative is not just about the power of the story but also about how it ‘feels’ truth, the Colbert ‘truthiness’ effect. It is insidious power of falsehoods like the great replacement. It is the enshrining of the Pilgrim foundation narrative and the ahistorical creation of Thanksgiving and its mythologies in US after the Civil Wars (cf. chapter one of this book).

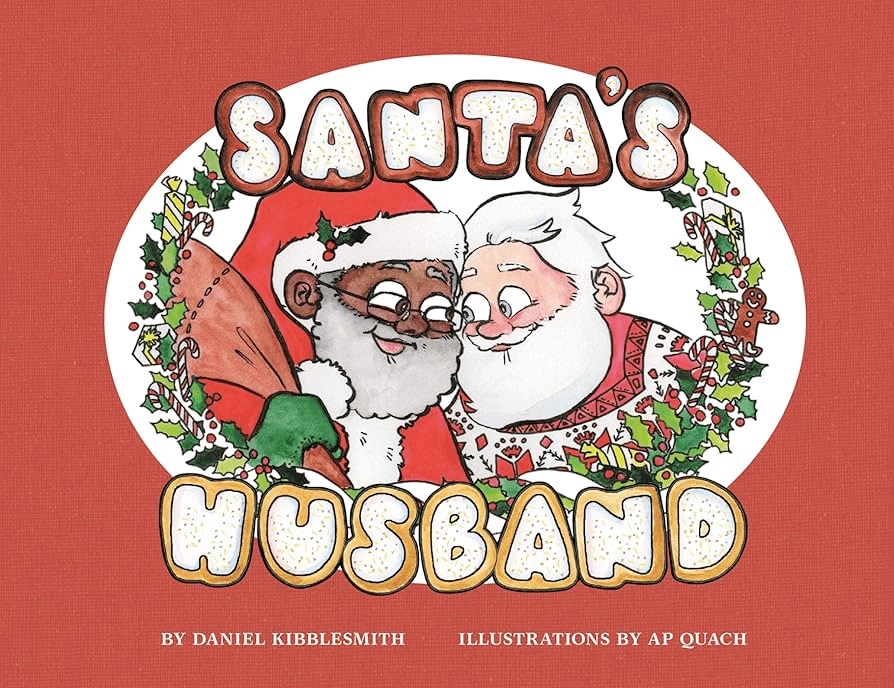

Let us take a favorite book of mine as a thought experiment.

My children have always had a present from David (Santa’s Husband) under the tree. When they ask about Mrs. Claus I tell them that is obviously Santa’s sister. Do my children believe this? Not really, maybe when they were younger. Will they give gifts to their own children from David? Maybe. This is pretty niche stuff. I like the book because it encodes inclusive values and takes pot shots at the so called “War on Christmas” narrative. It is an exercise is satirical myth-making.

If we were going to going to try to unpack the ‘origins’ of this story on this story we could talk about Coca Cola Santa and Nicholas of Myra and any number of other threads before we got back to Matthew and Luke and their shared source for the infancy narrative of Jesus and from there we might head into a study of savior births and the miracles said to accompany them probably leaning hard into the wise men from the East motif who bring gifts… Someone might want to bring in the Saturnalia and the appropriation of pre Christian solstice rituals. I’m open to that too and there is probably some validity in doing so. If we take authoring of Santa’s Husband as the tip of this cultural iceberg we can travel through pre existing narratives into deep time where we are left with only fragments and speculation. If we took a time machine and brought Santa’s Husband and a reasonable translator back thousands of years it would be illegible to Nicholas of Myra or Jesus of Nazareth, and yet it could not exist without those historical figures and those that loved them.

There is no kernel of truth and yet there is cultural connection and cultural values across broad sweeps of historical time through iterative narration. Roland Barthes said a myth at once true and unreal and that is what makes it a myth. As such Santa’s Husband for me (but not necessarily for you!) is about as truly mythical as any narrative can be, even as I can pinpoint its specific authorship and date of creation.

So what does this say about my reception of Wiseman on the Bolsena Mirror and Romulus and Remus? This is harder to articulate. Please bear with me as I think aloud.

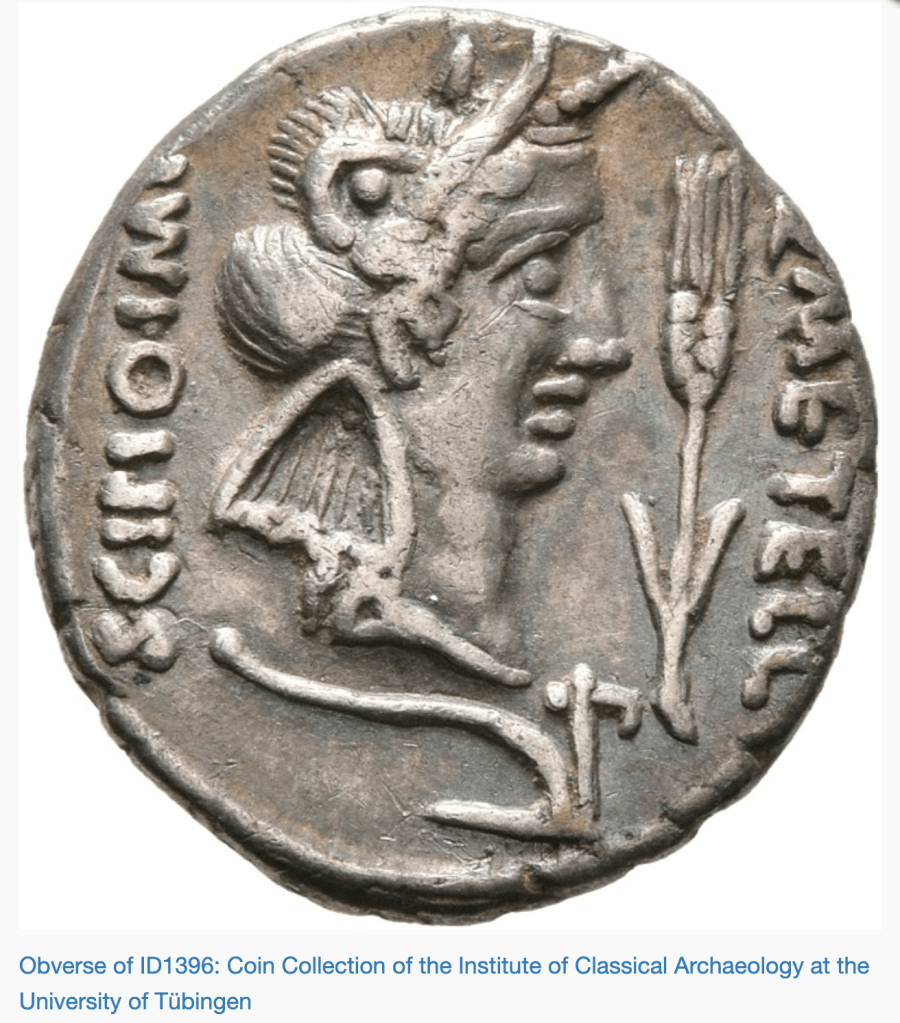

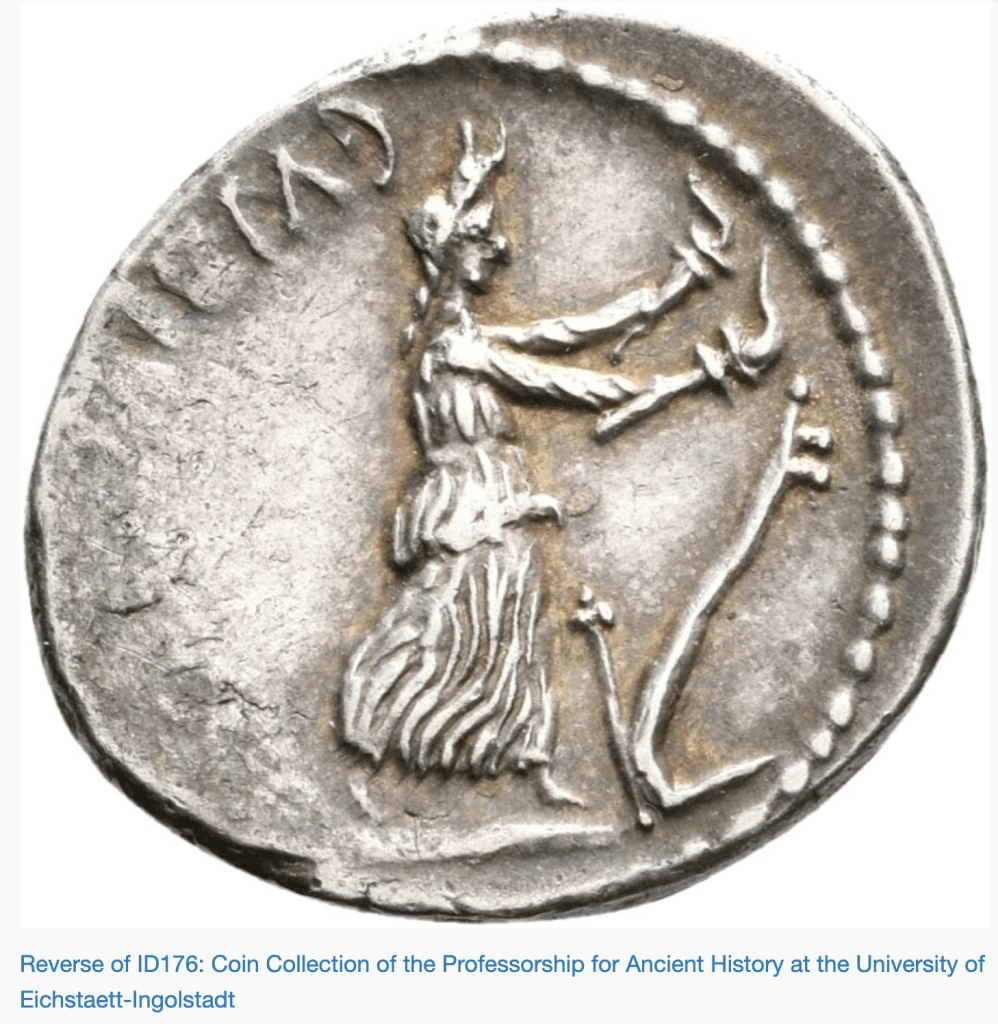

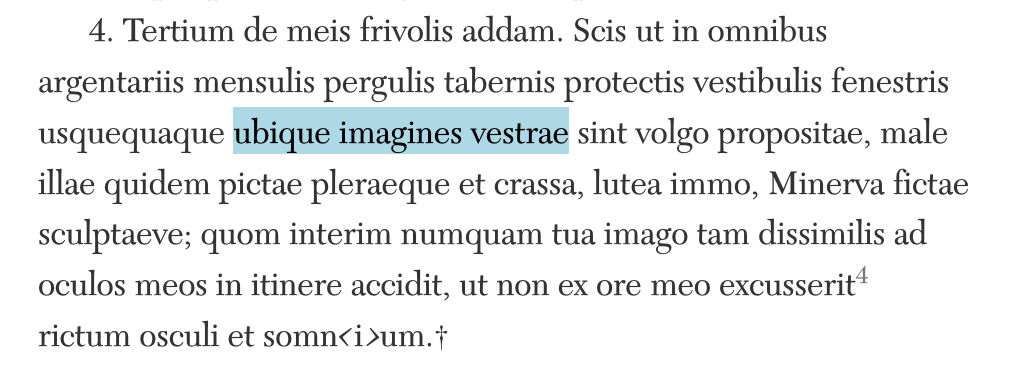

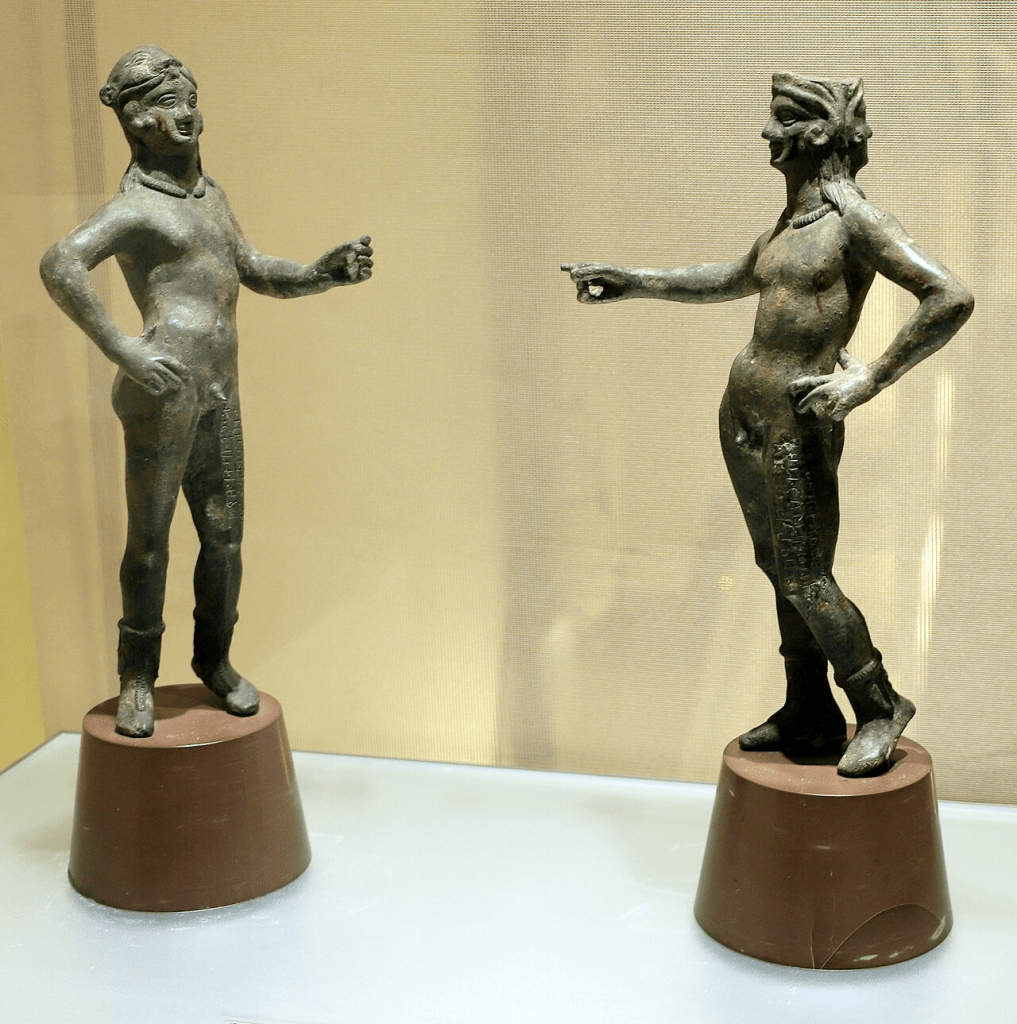

I think we cannot know what was in the mind of the creator of the mirror. I think we can say that the imagery must have resonated with the artist and patron and that similar imagery likely existed in other media, some lost, and much that was perishable. I think many different names could have been given to the figures and especially the twins. Plenty of similar bronze artifacts (mirrors, cista esp.) have inscriptions to clarify our interpretations. Without labels we today and ancient viewers are equally free to see what we want to see.

I cannot accept the mirror as a terminus post quem for myth creation. Because I do not see the existence of one plausible explanation (the birth of the Lares) as precluding another potentially equally ancient interpretation (Romulus and Remus) OR even another set of infants whose names are lost to us.

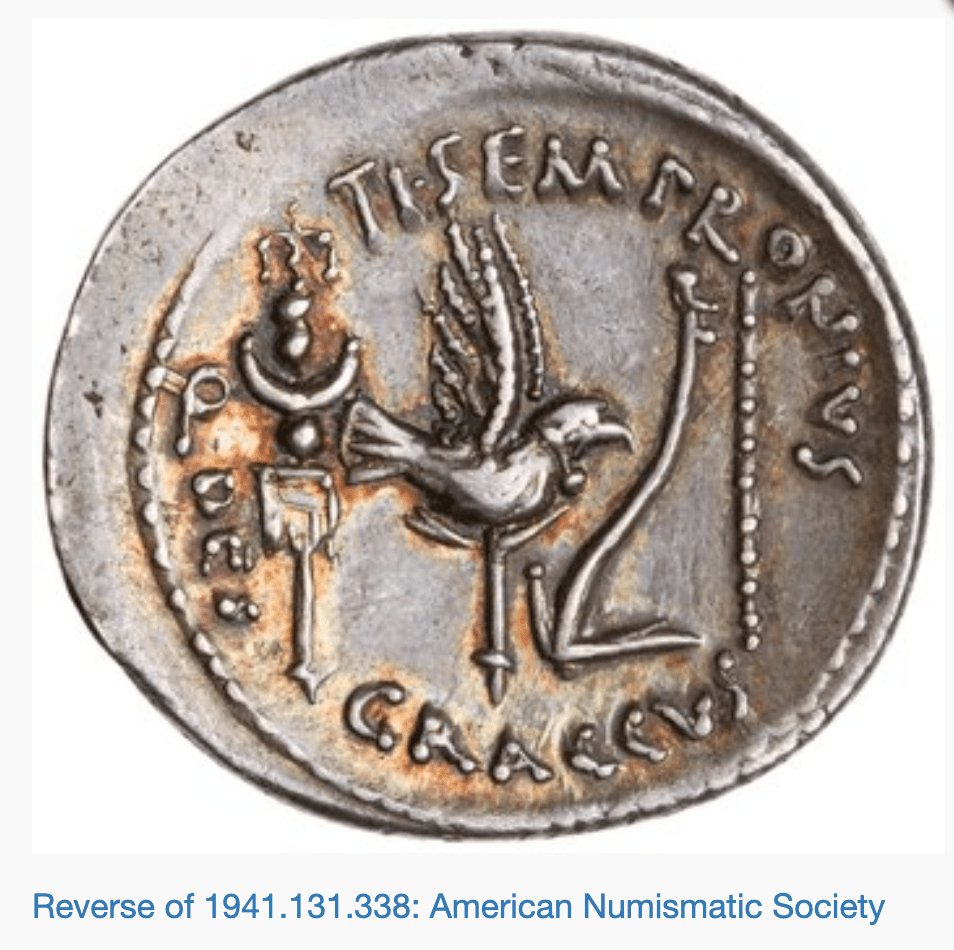

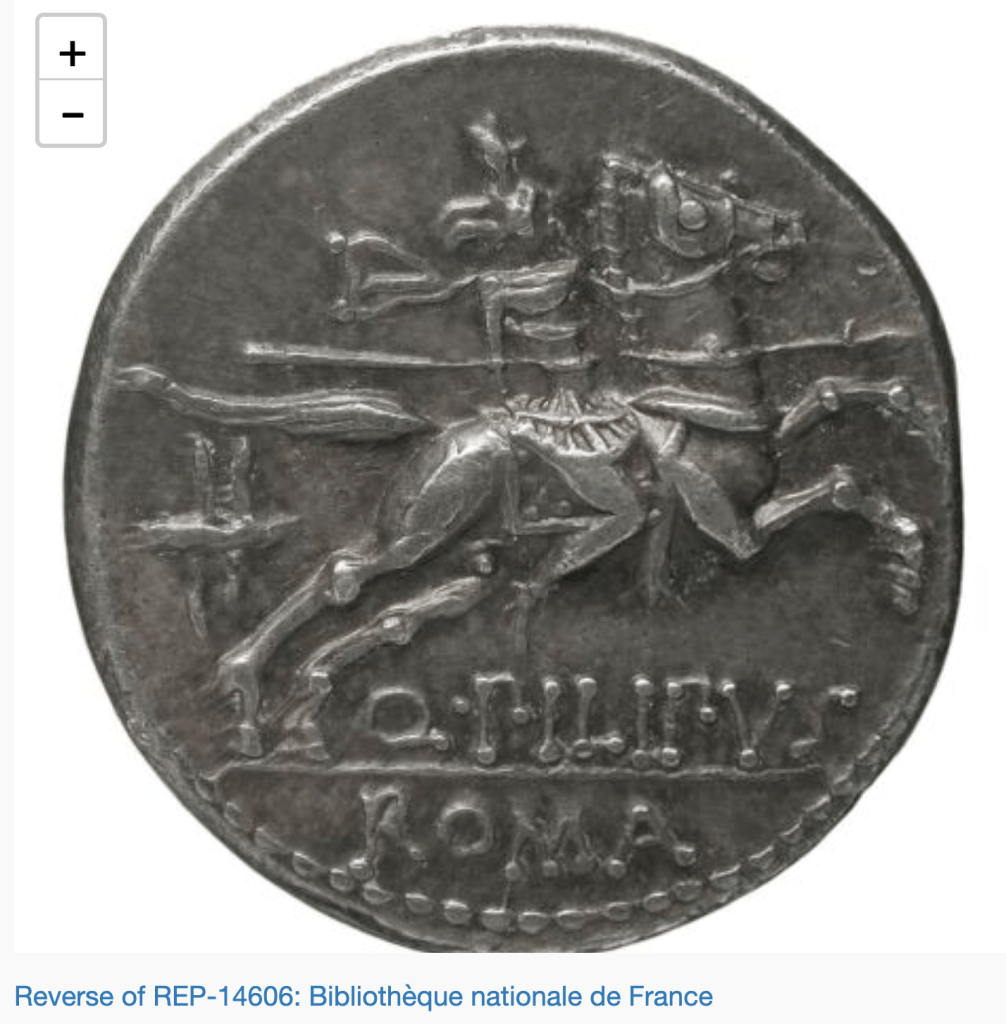

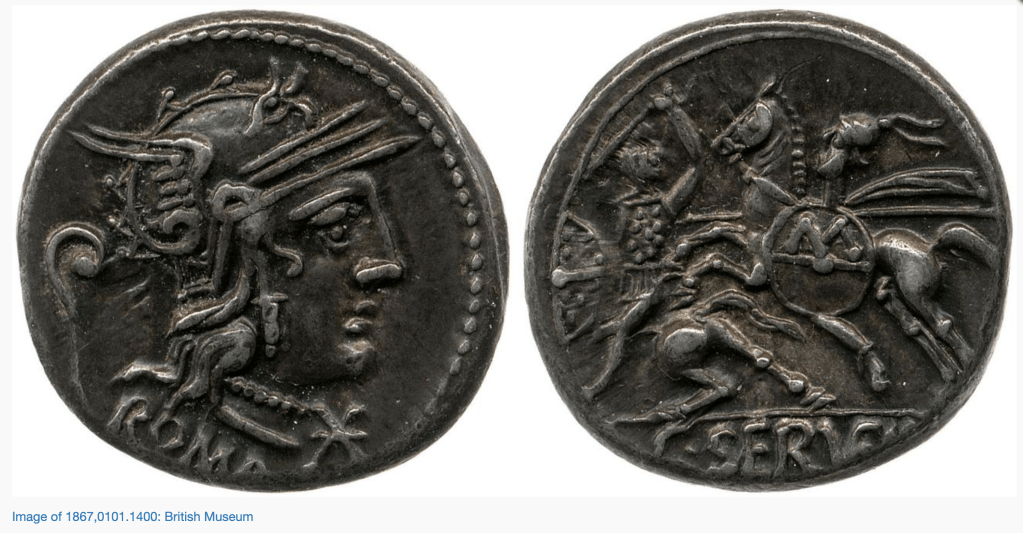

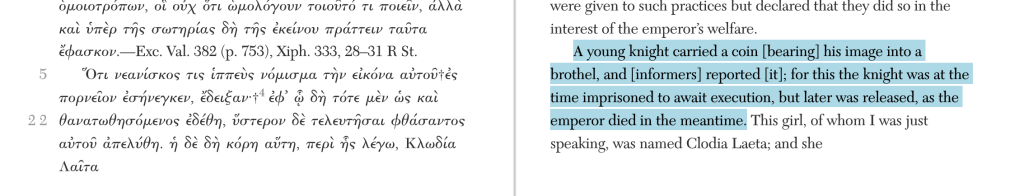

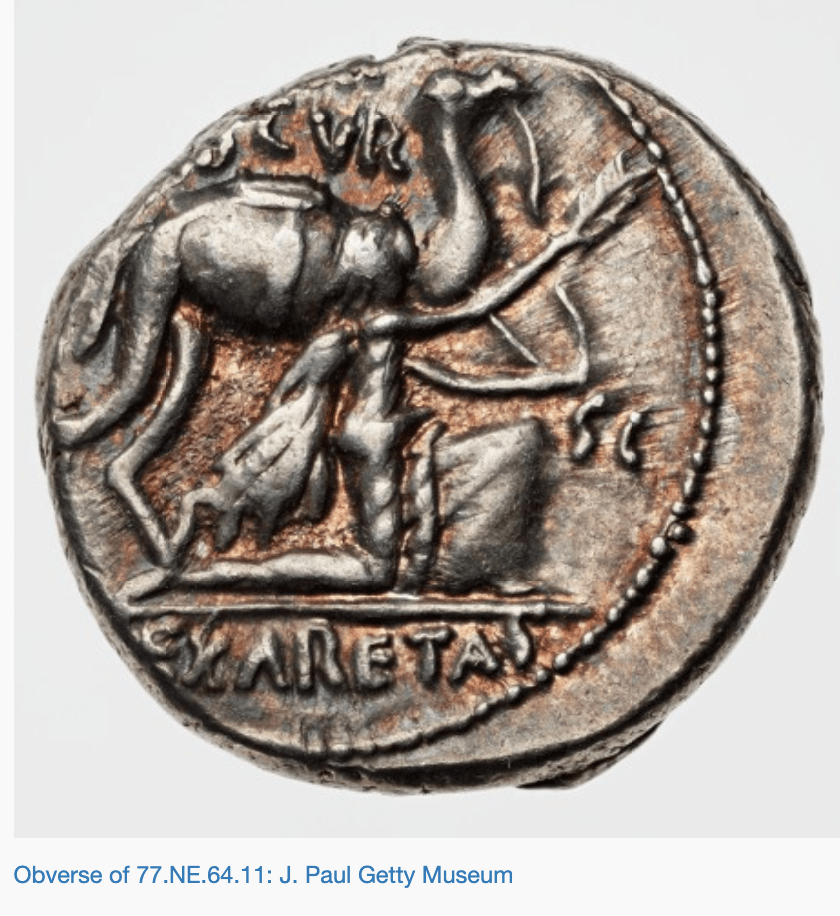

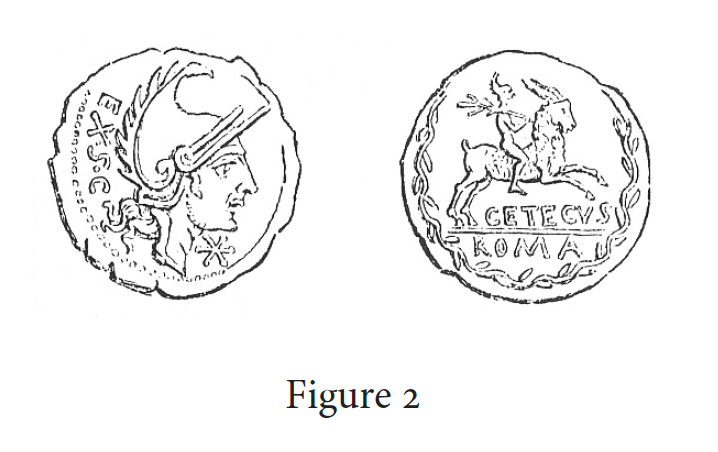

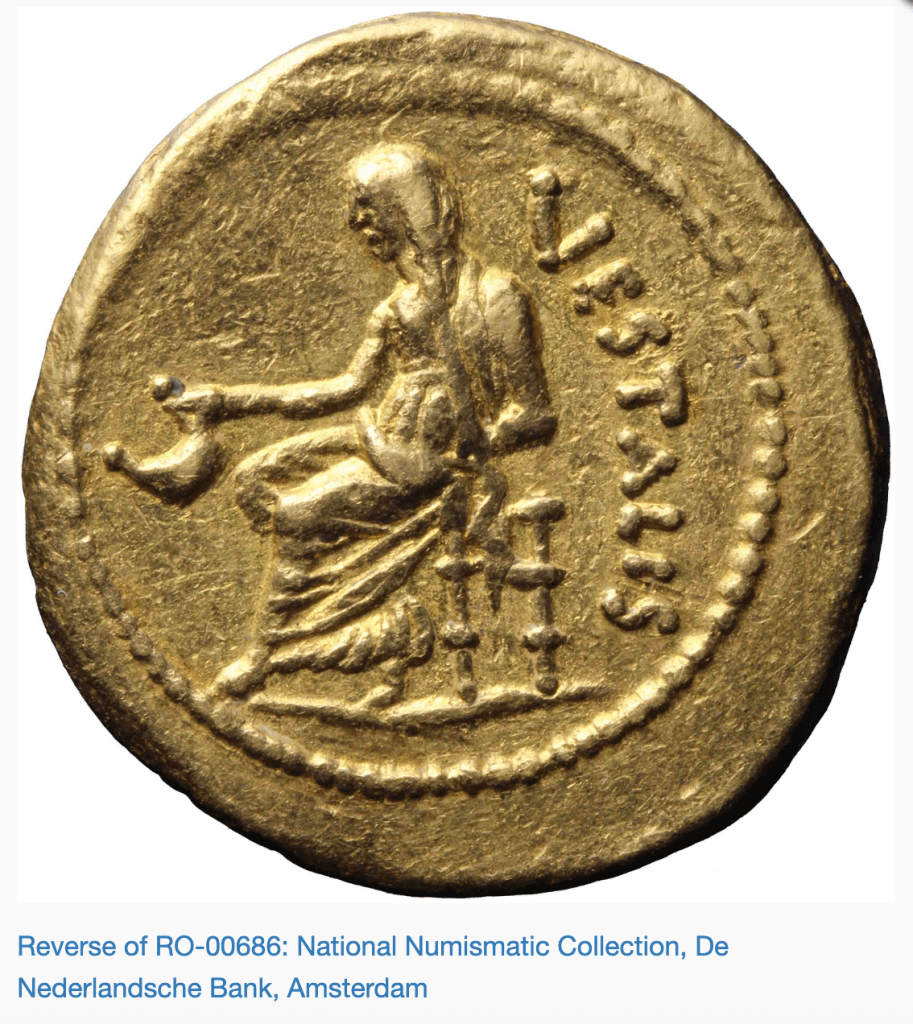

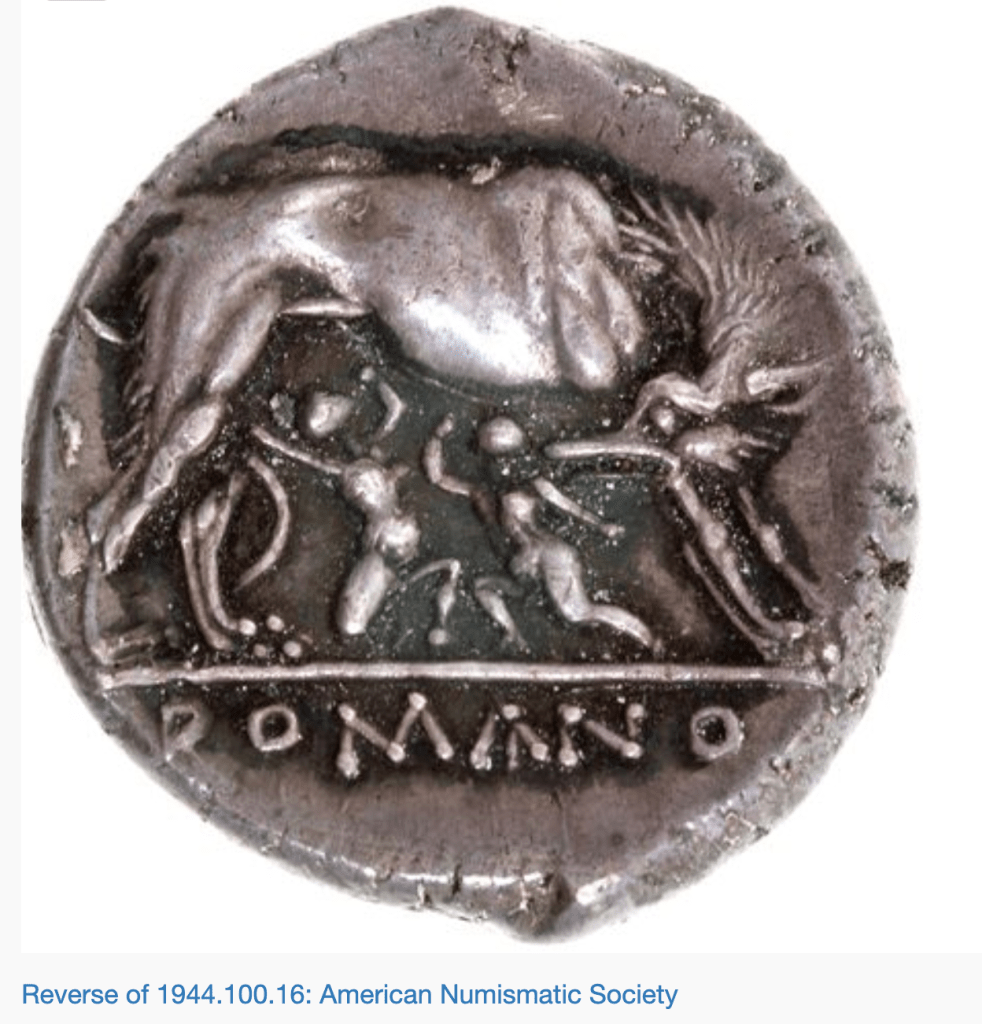

For years many scholars believed that RRC 20/1 must date to 269 BCE to make it line up with Livy, emphasizing that Ogulnius the consul of that year had earlier in his career set up a statue with a presumed similar subject and literary testimony places the creation of silver coins in this year.

The curule aediles, Cnaeus and Quintus Ogulnius, brought up several money-lenders for trial this year. The proportion of their fines which was paid into the treasury was devoted to various public objects; the wooden thresholds of the Capitol were replaced by bronze, silver vessels were made for the three tables in the shrine of Jupiter, and a statue of the god himself, seated in a four-horsed chariot, was set up on the roof. They also placed near the Ficus Ruminalis a group representing the Founders of the City as infants being suckled by the she-wolf. [ad ficum Ruminalem infantium conditorum urbis sub uberibus lupae posuerunt simulacra]. The street leading from the Porta Capena to the temple of Mars was paved, under their instructions, with stone slabs. Some graziers were also prosecuted for exceeding the number of cattle allowed them on the public land, and the plebeian aediles, L. Aelius Paetus and C. Fulvius Curvus, spent the money derived from their fines on public games and a set of golden bowls to be placed in the temple of Ceres.

Livy 10.23

The archeological record makes it impossible to date RRC 20/1 to 269 BCE (Burnett,

San Martino in Pensilis Hoard, 2006). It must be at the tail end or directly after the 1st Punic War. Also while many scholars have tried to make 269 for the introduction of silver ‘true’ in some way, this is again contrary to our archaeological evidence.

These are topics I’ve blogged about in dribs and drabs before. One key post on dating using texts versus archaeology. An early post on how Coarelli suggests the Lares may be the original founders of the city under the wolf and twins.

While Coarelli might be wrong about dating, he’s not wrong that there could (but need not) be overlap between the Lares as founders and Romulus and Remus as founders. We cannot know what was in the minds of the Ogulnii or their contemporary in 296 BCE. We cannot even know beyond a shadow of doubt if the attribution of the statue, its dates, the conditions and placement of its erection are accurate. Livy was wrong about the introduction of silver and many other things he could be wrong about this as well. If we want 296 BCE to be a firm date we need to trust Livy’s access to accurate records. Do we? Why? If it is inaccurate do we think Livy is making stuff up completely? OR, do we blame an unknown intermediary for falsification.

Does it matter? Clearly it matters to Wiseman and many others. And yet, I do not think I care overly much. Livy is only certain proof only Livy’s own historical discretion. When we try to using Livy or any author to interpret the more distant past from which we only have elusive material culture and minimal textual testimony, then we must allow there must be a potential for inaccuracy and hold some skepticism of it all. To me the question is not who is depicted on the Bolsena Mirror but what is possible and plausible. What is the range of explanations we might consider.

Yes storytelling, theater, and other ‘proto’ literary moments could and likely did radically influence how the Romans and others thought about the origins of city. Yet, I would emphasize that for those narratives to contain share power in the formation of communal identity they must contain something of what Barthes describes of myth that which is at once true and unreal. The unrealness makes the narrative malliable and open to interpretation and reformulation. The truth need not be literal but the ethical and cultural resonance embodied in the narrative. Truth can also be in how the narrative forms a plausible connection to the unknowable but desired past that is essential because of the present reality as experienced by the audience.

Now, if any nation ought to be allowed to claim a sacred origin and point back to a divine paternity that nation is Rome. For such is her renown in war that when she chooses to represent Mars as her own and her founder’s father, the nations of the world accept the statement with the same equanimity with which they accept her dominion.

Livy Preface

Huh.

I had a lot say. I think I have more to say as well. But I might need to get up and walk about and shake my head a bit.

See you soon.