I need a stemma; I was getting confused about Marius, Gratidianus, Cicero and the Arpinum family connections. Those names in color are the famous ones.

adventures in my head

Diod. 38.4:

App. BC 1.74

Cic. deOrat. 3.9: For we ourselves remember, that Quintus Catulus, a man distinguished for almost every type of merit, when he entreated, not the security of his fortunes, but retreat into exile, was forced to deprive himself of life.

Cic. Brut. 4.307: In the same year Sulpicius lost his life; and Q. Catulus, M. Antonius, and C. Julius, three orators, who were partly contemporary with each other, were most inhumanly put to death.

Cic. Tusc. 5.56: Was not Marius happier, I pray you, when he shared the glory of the victory gained over the Cimbrians with his colleague Catulus (who was almost another Laelius, for I look upon the two men as very like one another,) than when, conqueror in the civil war, he in a passion answered the friends of Catulus, who were interceding for him, “Let him die” ? And this answer he gave, not once only, but often. But in such a case, he was happier who submitted to that barbarous decree than he who issued it. And it is better to receive an injury than to do one; and so it was better to advance a little to meet that death that was making its approaches, as Catulus did, than, like Marius, to sully the glory of six consulships, and disgrace his latter days, by the death of such a man.

Cic. Nat Deo 3.80-81: Why before that were so many leading citizens also made away with by Cinna? why had that monster of treachery Gaius Marius the power to order the death of that noblest of mankind, Quintus Catulus? The day would be too short if I desired to recount the good men visited by misfortune; and equally so were I to mention the wicked who have prospered exceedingly. For why did Marius die so happily in his own home, an old man and consul for the seventh time? why did that monster of cruelty Cinna lord it for so long? You will say that he was punished. It would have been better for him to be hindered and prevented from murdering so many eminent men, than finally to be punished in his turn.

Vell. 2.22.4: then there was Quintus Catulus, renowned for his virtues in general and for the glory, which he had shared with Marius, of having won the Cimbrian war; when he was being hunted down for death, he shut himself in a room that had lately been plastered with lime and sand; then he brought fire that it might cause a powerful vapour to issue from the plaster, and by breathing the poisonous air and then holding his breath he died a death according rather with his enemies’ wishes than with their judgement.

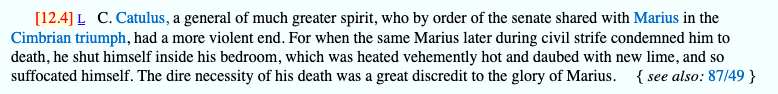

Val. Max. 9.12.4

Plut. Mar. 44

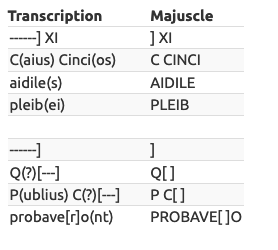

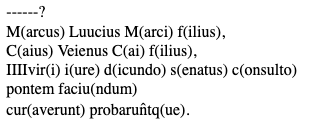

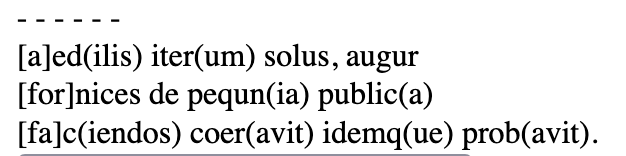

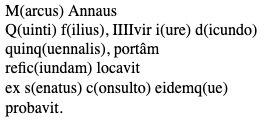

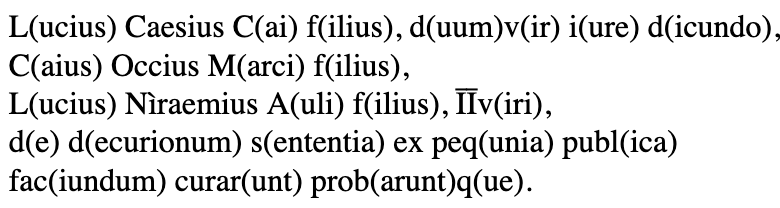

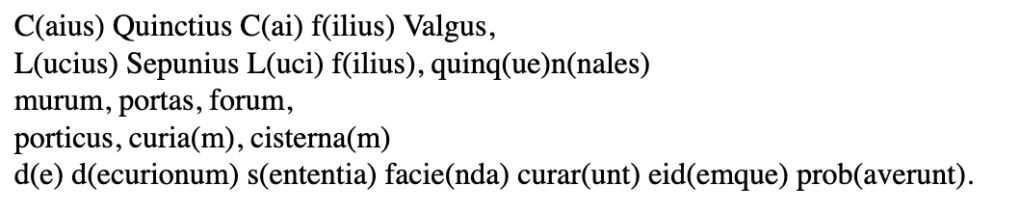

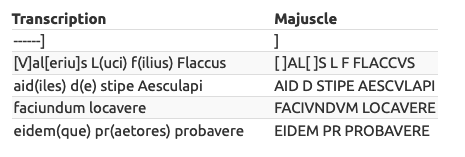

This is a follow up to a literary survey done earlier this year also on this blog. Egadi Ram inscriptions are excluding here, but remain our earliest testimony of this language. I’ve excluded inscriptions post 50 BCE.

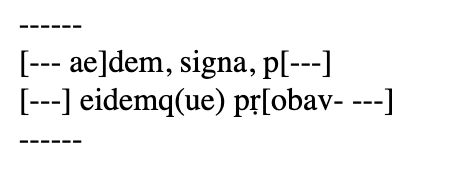

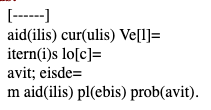

Cf. Bernard 2018: 155-156 on probatio in early Roman state contracts. I’m dying to write up my thoughts on these inscriptions now but for now I’ll leave myself some notes about next steps.

Notice who is initiating action vs. who is completing the action. Most interesting is where it is not isdem or eisdem. What is the official role of the individuals able to take these actions? What class of things must be probare? Walls, temples, pavements, more… The first initiating verb varies, but curare (+gerundive) and locare most common. Locare appears later.

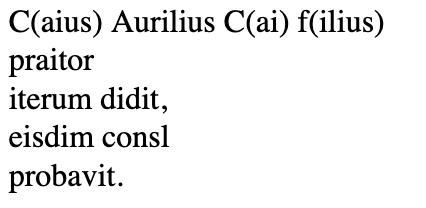

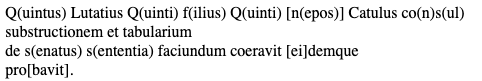

230-210 BCE, ROME (AE 1896, 0038)

230-180 BCE, Praeneste, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 2439)

230-171 BCE, Hadria (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 3292a)

202 BCE, Nemi (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0610)

202-80 BCE, Luceria (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1710)

200-101, Hadria, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1896)

200-101, Rome (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0024)

170-131 BCE, Rome

earlier post on mosaic pavement inscription from temple of Apollo

170-131 BCE, Cora (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1511)

170-131 BCE, Setia, (AE 1997, 0283)

144 OR 108 BCE, Tarracina, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0694)

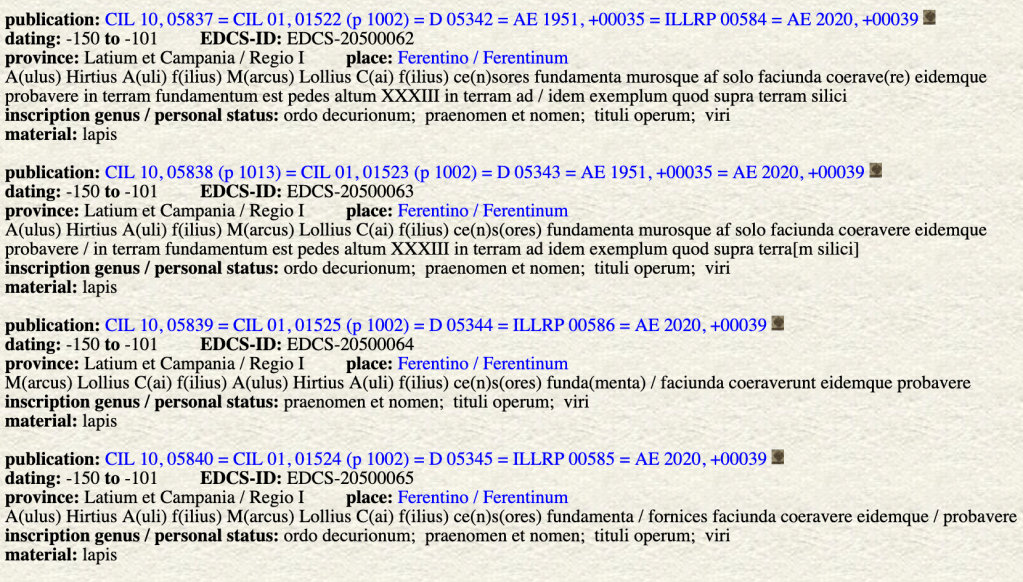

150-101 BCE, Ferentino, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1522-1525

150-100 BCE, Rome (CIL 06, 39859)

130-101 BCE, Cora (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1506 and CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1507)

130-71 BCE, Fondi (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1559)

130-51 BCE, Rome (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1001)

125/120 BCE, Rome (Tiber Island) (CIL 06, 40896a)

C(aius) Serveili(us) M(arci) f(ilius) pr(aetor) [—?, C(aius), M(arcus), P(ublius)?] Serveilieis C(ai) f(ilii) faciendum coeraverunt eidemque probavẹ[runt].

MOSAIC!

110-91 BCE, Treicesimo (CIL 01, (2 ed.) 2, 2648)

100-80 BCE, Formia (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1565)

100-71 BCE, Narnia (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 2097)

100-51 BCE, Fondi (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1560)

100-51 BCE, Capua (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 2949)

100-51 BCE, Spoletium (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 2107)

100-50 BCE, Formia (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1564)

90-75 BCE, Genusia (AE 2017, 0258)

90-71 BCE, Telesia (CIL 09, 02233)

[3] Minuci[us 3] /

Balbus pr(aetores) d[uoviri 3] /

d(e) d(ecurionum) s(ententia) fa[ci]u[nd 3 curaver(unt)] /

{e}idemque [probaverunt]

90-51 BCE, Aquileia (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 2198)

80-61 BCE, Pompeii, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1628, CIL 01, 2 ed., 1635, CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1629)

80-51 BCE, Praeneste, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1464)

80-50 BCE, Abella, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1609)

80-50 BCE, Caiatia (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1576)

78/65 BCE, Rome (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0736, CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0737)

78-51 BCE, Aeculanum (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 3191)

70-50 BCE, Cosilium (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 1686)

70-31 BCE, Marsi Marruvium (Cerfennia statio) (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 3210a)

63 BCE, Rome (CIL 01 (2. ed.) 02, 800)

62 BCE, Rome (ponte Fabricio!) (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0751 a, b, c, e, g, h)

55 BCE, Issa, (CIL 01 (2 ed) 02, 00759)

55 BCE, Interamnia Praetuttiorum, (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0765)

1st cent BCE? city of Rome, private not public contract (CIL 1(2) 2519)

Inscription dates to 75-100 CE, but records events of 63 and 58 BCE, Ostia, (CIL 14, 04707)

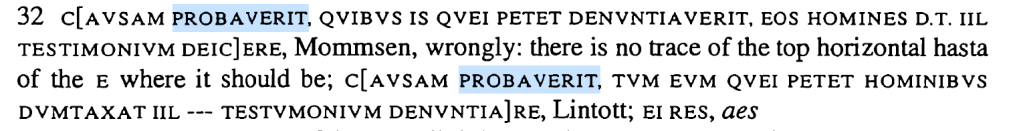

Mommsen and Lintott both restored at line 31 probaverit on the Tabula Bembina (CIL 01 (2 ed.), 0583), but this is no longer favored by most scholars, dated 123/111 BCE. (Screen shot from Roman Statutes on file)

… I am writing for my school newspaper article on the benefits of taking a classical language such as Latin. I am interested in learning what experts think about the benefits of taking a “dead” language, such as Latin. I am currently in Latin 2 and my friends (and their parents) ask me this question all the time. …

A young correspondent

When one gets an email like this, it feels important to answer from the heart. So I took some time this Monday morning to reflect. Here’s part of my answer.

All languages open us to understanding different cultures. Historic languages give us deeper more meaningful insights into our shared human past. I’m a historian so the main function of my own learning of Latin and Greek is to get closer to my historical sources.

Moreover, all language learning deepens our understanding of our own language(s). Some say this benefit is more directly realized in Latin because of how its grammatical system has been so rigorously articulated over the millennia, but this depends on how you are learning the language and if that approach works for you. Think of it this way, if your head is full of strange things like conditional clauses, moods, genitives, and gerundives, you cannot help but see analogous constructions in English or any other language you speak or learn now or in future.

For those scared of language learning, Latin can feel like a safe starting space often with fewer pressures to perform or improvise. I was placed in Latin because back in the 1990s my learning disabilities meant my high school teachers thought I couldn’t learn a spoken language. It took me decades to stop believing they were right. I finally tried immersion Turkish ‘for fun’. Unlike for my classmates, the grammar came easily to me. I understand how languages function, even when the new language has few to no Indo-European or even Semitic loan words or shared syntax or grammar. Speaking other languages is still challenging for me, but so is speaking English. (I’m still super grateful for my seven years of speech therapy). Latin gave me the confidence to maximize my own abilities and led me to a career in history that continues to bring me daily joys.

Finally, don’t underestimate the role of pleasure from any form of knowledge acquisition. When we do something hard and make progress through disciplined learning, it feels good! There is nothing wrong with wanting to challenge yourself and engage with any academic subject because it gives you deep personal satisfaction. That feeling is how we find our drive in life. If we only value training and not learning, we would be denying part of our humanity.

Sometimes it helps to flip the question on the person asking. Why do you ask? Were there subjects in your own education that seemed impractical at the time but you now value for the experience or knowledge? What challenges have you taken on in your own life? Why did you decide to stick with that challenge? What do you think the function of high school and college learning should be? Why? What happens when the practical skills we may learn along the way become out-of-date in this rapidly changing world?

Update:

Colleagues have helped me think even more about this topic. There has been much discussion of how Latin has come to be associated with class in the Anglophone world and how it was a marker of European power historically. I thought it might be useful to add some bibliography to my post:

Waquet Françoise. 2001. Latin or the Empire of a Sign : From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. London: Verso.

Ellsworth Hamann Byron. 2015. The Translations of Nebrija : Languaje Culture and Circulation in Early Modern World. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Morley Neville. 2018. Classics : Why It Matters. Cambridge UK: Polity Press.

Goff Barbara E. 2013. Your Secret Language : Classics in the British Colonies of West Africa. London: Bloomsbury.

Further reading suggestions welcome.

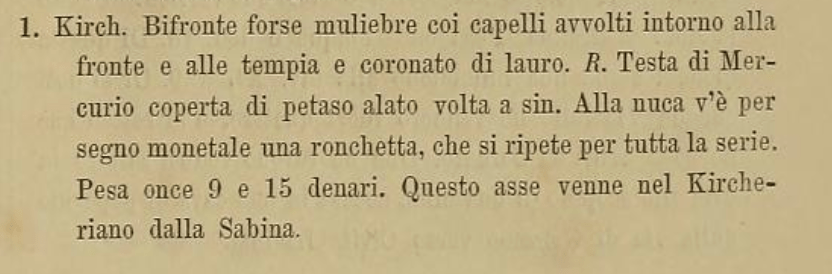

Generally when I see something as from Museo Kircheriano (cf. Marchi catalogue), I assume it ended up in the Museo Nazionale in Rome but we also know some stuff was dispersed. New to me today is that much of the material I find so fascinating from this collection seems to have sold in 1914 in the Hirsch Sale.

Secondina Lorenza Cesano in AMIIN 2, Roma 1915 pp. 49-180

G. is an abbreviation for Garrucci.

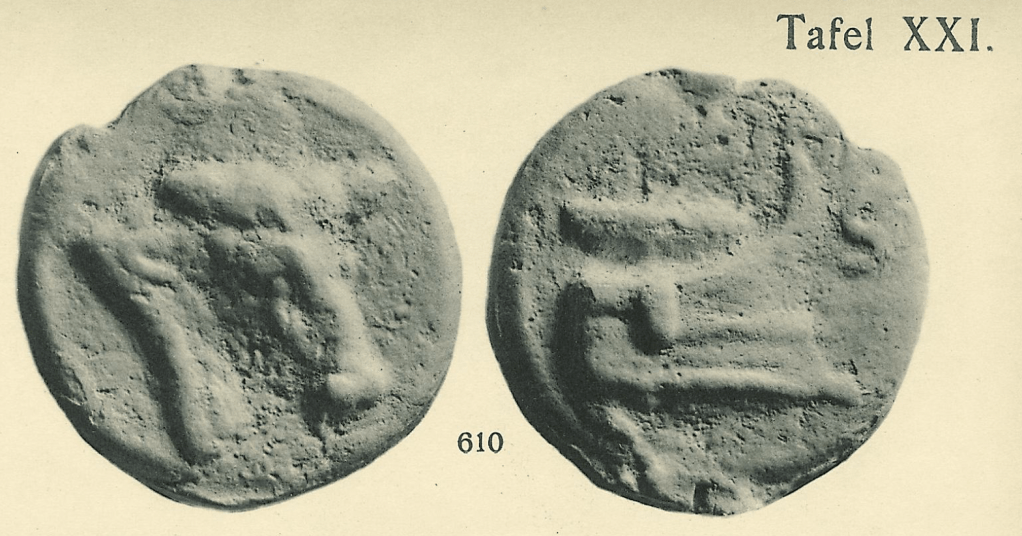

Notice how the damage at the top of the reverse is very similar. The same specimen was also known to Marchi in 1839.

I should have realized it when I’d blogged about this same auction here. At least I leave myself footprints to follow back. Here’s where I was first reading Garrucci I didn’t notice it was the same specimen as he only had a terrible drawing. So file this post under bull prow Praeneste,

All Dies Exemplar will need to be cross checked with Garrucci, but even some where it does not say this or give other provenience hint Kirchner may be the original source:

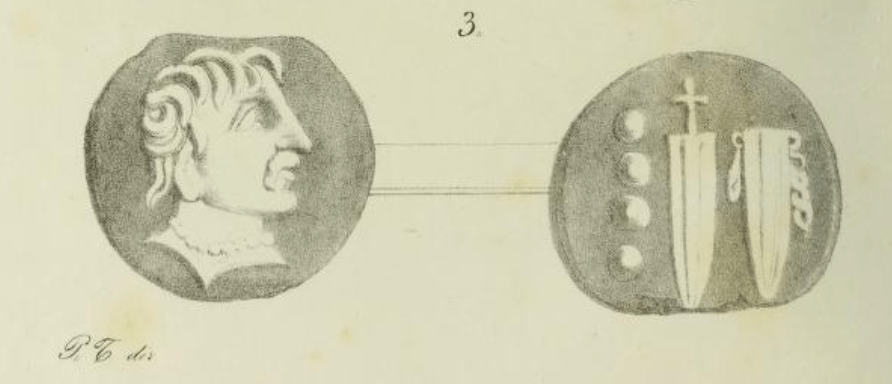

This look like the bad drawing in Marchi. Notice the flattened top and bottom. Interestingly this type was apparently unknown in 1767 to Passeri.

Earlier posts on Ariminum aes grave.

BUT

For the record this might be nonsense or it might be old news, but to me today it was an interesting distraction.

I got here because I’m thinking about RRC 25/1, so I was worrying about the origins of this specimen

Here’s Garrucci:

Notice in the drawing (however simple) that the flaws near the bottom sprue and void above Janus head are still obvious. The drawing appears better than one might expect.

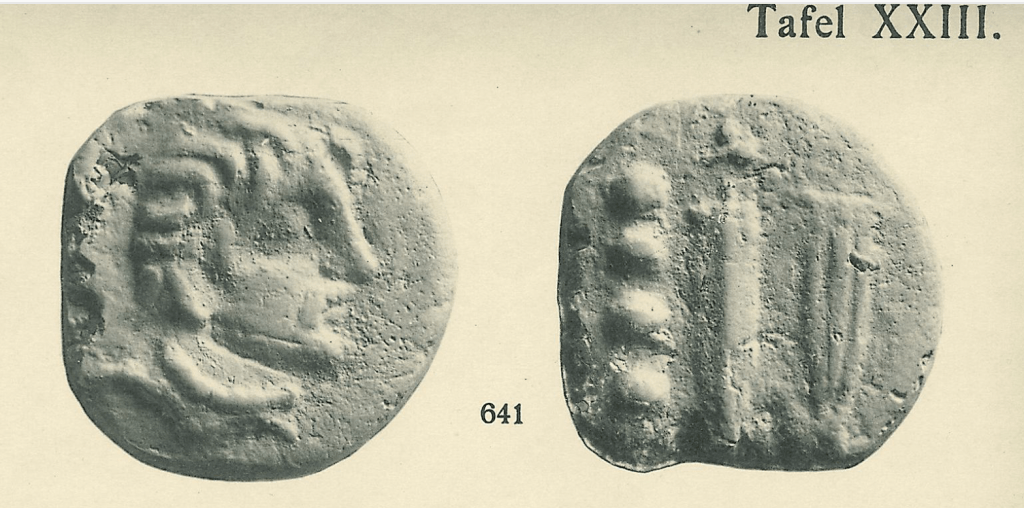

This is Marchi’s illustration of the same coin from 1839. It marks the tell tale void above Mercury’s head and the unique shape of the wing on the helmet. Also on the Janus side the nick at the top and then the cut on the right side of inner rim also match. Although Marchi’s catalogue is officially of specimens from the Kircher collection, we know that some of the specimens he illustrates were later found in other museums, cf. the Ariminum coin discussed above and also from that same series the whole unit, known to Garrucci to be in Pesaro and also found there and documented by cast and photography by Haeberlin, and already known in 1767 in the collection of Passerii.

The coin was ostensibly still in Rome when Haeberlin says he saw it, BUT his cast doesn’t look anything like Garrucci’s plate, it is clearly a different specimen. He says the one he saw was from Sabina like Garrucci’s. What happened?!!

I have an article on uncia in the late republic in the works but this led to my interest in the semuncia. There are blog posts on this from back in 2021 (but updated more recently with new material). And, then again more recently from my dive into the Vicarello material for a Lucerian specimen where I independently came to the same conclusions about a Crawford type as McCabe (his work is also forthcoming).

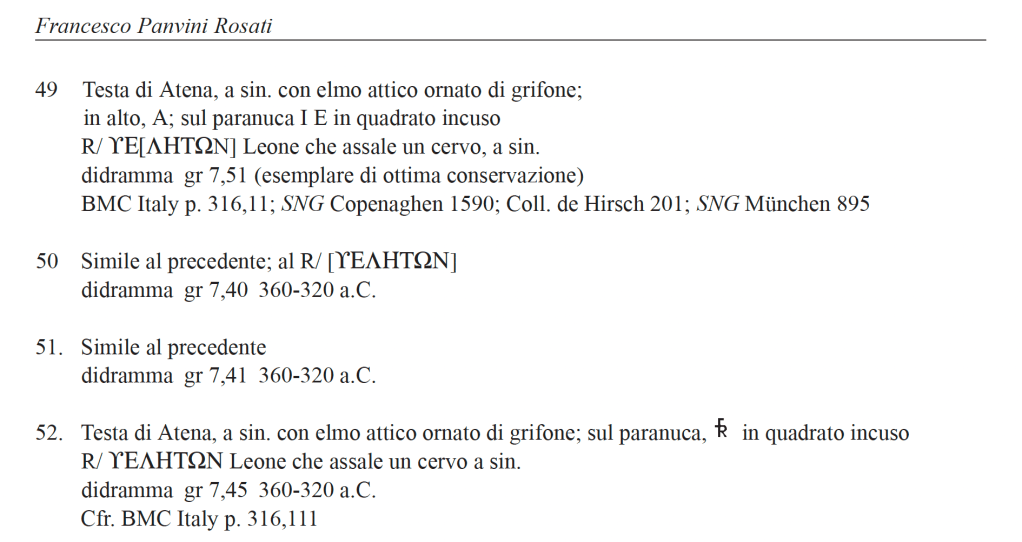

As I was thinking about putting the final touches on that article, I was checking for potential new material and the above Lucerian specimen came up in my searches (HNItaly 683). There is one in Paris, none in the BM or ANS, 7 have appeared since 2006 in trade).

The type is closely derived from the earlier cast semunciae for the same mint (HNItaly 675 and 677f):

The crescent provides continuity in the shift from cast to struck during the course of the second punic war. Moreover, the crescent helps to explain the selection of Diana for the obverse of struck materials.

Does it also explain why Diana appears on some struck semuncia of the Roman republic? We have two specimens of RRC 160/5 which are our earliest Roman Diana on the semuncia thus far. In fact the first Diana on any Roman coin known to date.

Crawford dates this issue to c. 179-170 BCE.

Diana is then ‘revived’ on some of the semuncia of the last decade of the 2nd century BCE (see earlier post).

I thought I’d written about this Durmius type, but apparently I haven’t. I was thinking about a possible butterfly on the Fabatus control marks and say this coin again.

Compare this control mark on RRC 408/1:

Instead of a crab we have a scorpion holding the butterfly. Both the Crab and Scorpion are zodiac signs (Cancer, Scorpio) and butterfly represents the soul. This strikes me as key to understanding the symbolism.

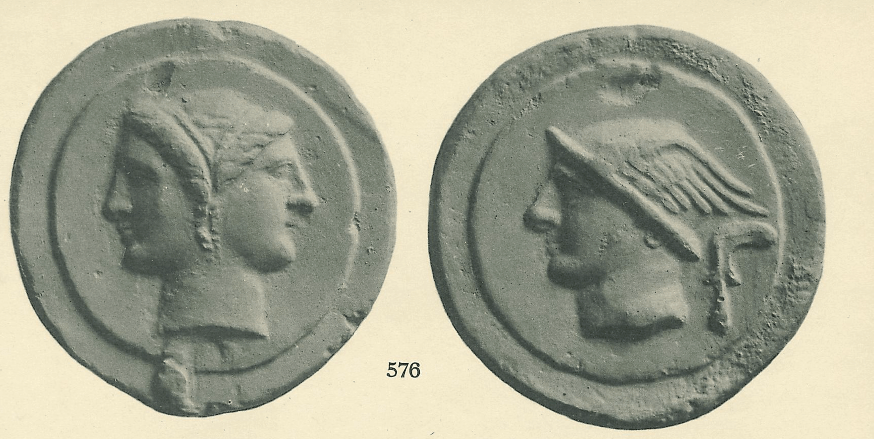

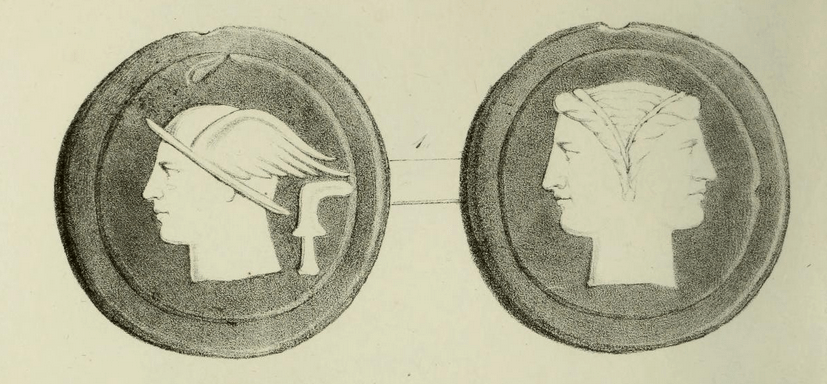

This is a screenshot of some coins from Velia in the Oppido Lucano hoard (most famous for having a specimen of RRC 13/1 in it).

My eye stuck on those incuse squares behind the head of Athena. They look so much like counter marks, but they are not! Here’s the catalogue entry. This is HN 1318.

This space behind the neck of Athena but inside the curve of the plume of the helmet is just where Velia places secondary symbols. Presumably correlated to the issuer or issuing of the coins.

Here’s an image of a Paris specimen to let you see the incuse better:

Velia did in the early days of its coin issue strike series with incuse punch reverses, but that doesn’t seem to be the inspiration for this unusual secondary symbol.

The shear complexity of the Velia issues and their symbols have kept numismatists happily and busily obsessed over the years. Rutter in Historia Numorum Italy is usually v v terse, but he lets Velia stretch to 6 pages resorting to a chart at one point.

One more just for fun. This is HN 1308.

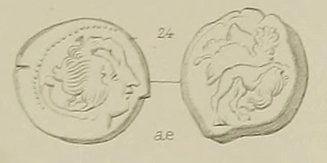

Some where in the basement of Palazzo Massimo lurks this coin seen by Bahrfeldt and illustrated by Garrucci. It comes from Vicarello hence my present interest.

The under type is said to be HN Italy 680, Luceria:

The problem is that right now this Lucerian coin is dated to c. 217-211 BCE way too late to be an undertype for RRC 16.

So what is going on?!

If I ever get into see coins in this collection this is now top of my list for personal inspection….

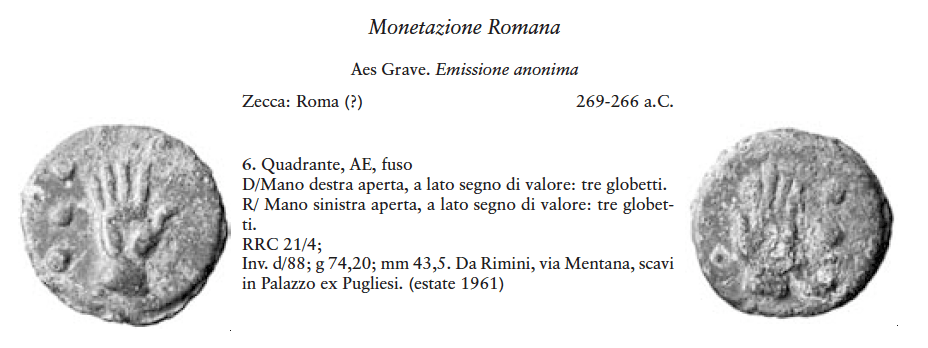

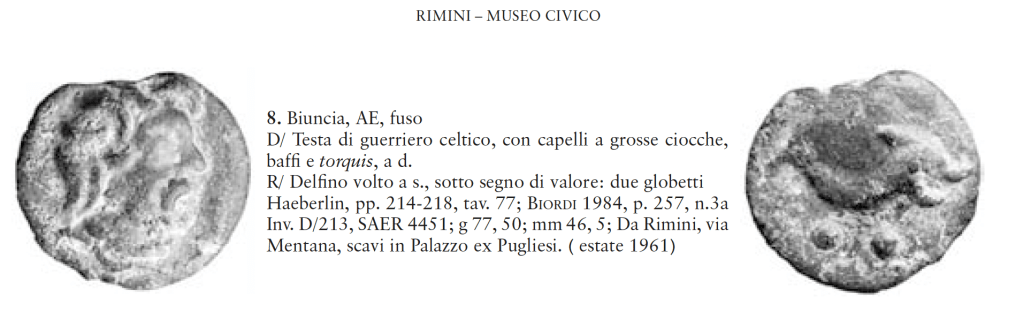

From the catalogue at the end of:

Ercolani Cocchi, Emanuela, Anna Lina Morelli, and Diana Neri. Romanizzazione E Moneta: La Testimonianza Dei Rinvenimenti Dall’Emilia Romagna. Firenze: All’insegna del giglio, 2004.

I’m struck not only by these two coins appearing in the same excavation. Were they found together?! But also by their similarity in size.

Ariminum is a Roman foundation of 268 BCE. According to another publication (below), there is also said to have been found in Rimini an RRC 18/1 and also in their collection RRC 18/4 and 18/5, suggesting they were also found in the area.

I’d be very inclined to invoke this as evidence to down date RRC 18 to after 268 BCE. I’d do that any way but this helps solidify my thinking.

in the 2007 publication