Please congratulate me for resisting naming this blog “something, something Wednesday” and thus making it even harder to resist such a title tomorrow.

After lunch yesterday I got to reflecting on what intellectual work I was really itching to do. I almost wrote an extension of that morning’s post on myth but with a focus on how I read fragmentary texts, ancient cultures of citation, and my general philosophy of historiography. I decided, while that might be a fun writing exercise, I’m already on record with a great deal of this. Not just my 2006 book, but also my 2018 Diodorus article and my forthcoming piece on Dionysius in the CUP volume Making Sense of Monarchy (link to my publications). It didn’t feel like a good use of LIBRARY time. I’m enjoying the gift of research time, but I’m so out of the habit of being in research libraries I forget to indulge in the books themselves. There is also voice in my head that says that writing and focusing on publication goals is more ‘productive’ than exposing myself to new things. That might be true to a point, but a good deal of the joy of being specifically here at ICS are the BOOKS, specifically the major catalogues and reference works.

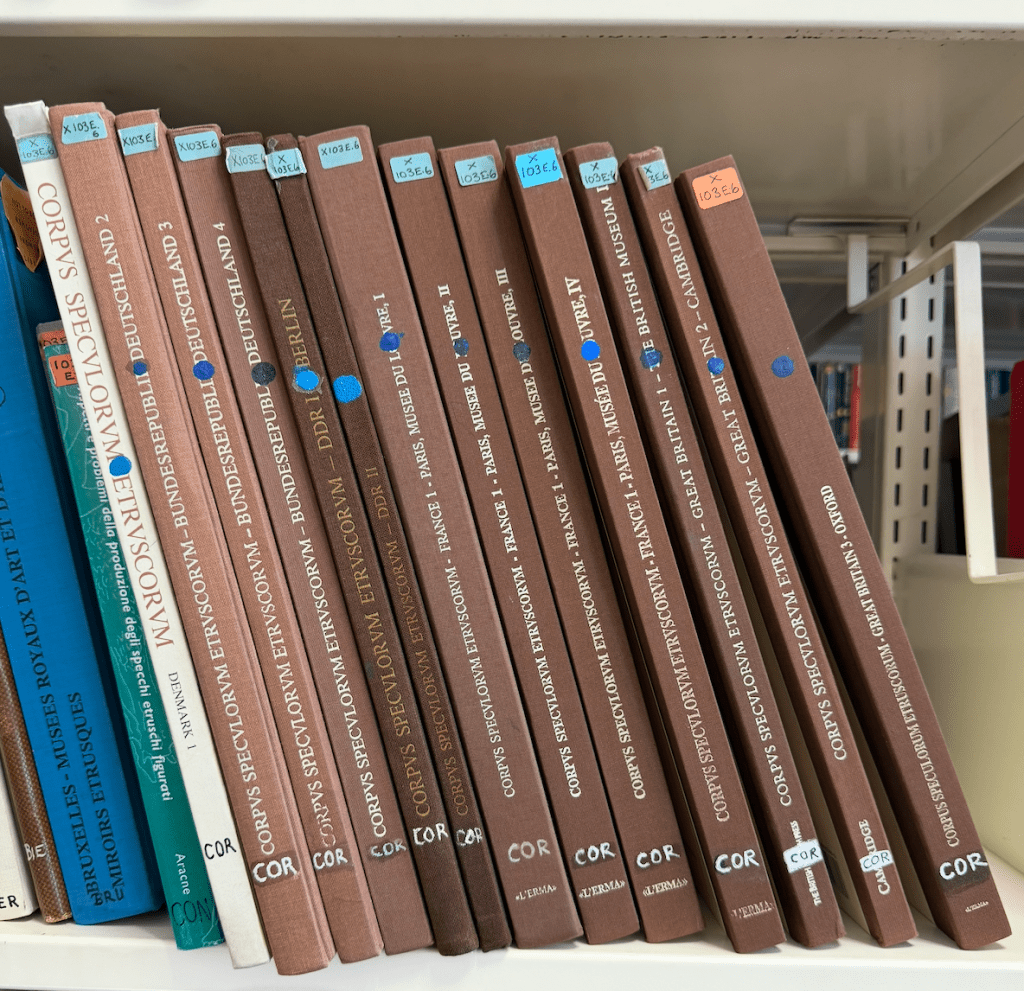

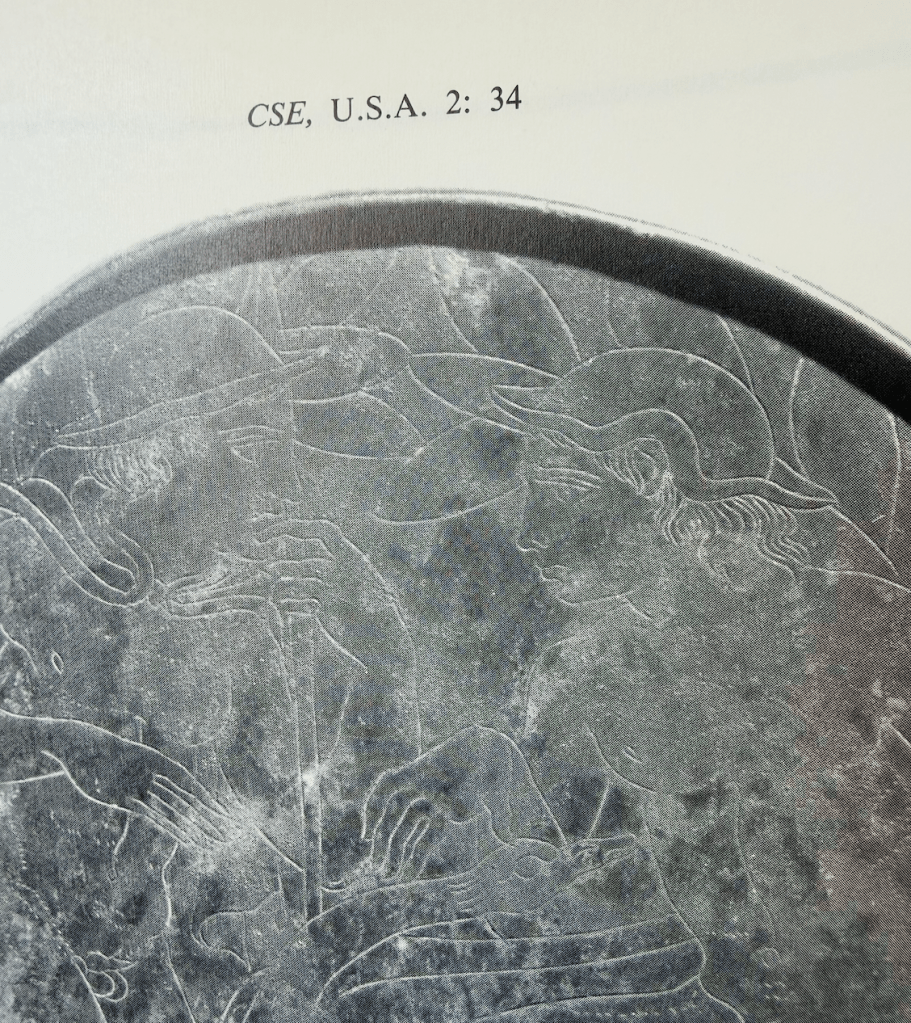

Meet the Corpus of Etruscan Mirrors, or officially Corpus Speculorum Etruscorum,

Ok so it is no SNG in scale of series but it is a monster of a late 20th century project, one of those like LIMC that I’d love see fully digitized, updated, and continued. It is massive but more mirrors do exist outside this standard reference work.

I decided that I didn’t feel confident in talking about the Bolsena mirror with wolf and twins because while I love the genre of Etruscan mirrors I’ve never made a systematic review of them, just oooo-ed and aaaah-ed as I went along. Think of it like how your perspective changes on a coin when you sit down and work through trays upon trays of coins within a given series. Or how great it is just to go through Schaefer’s Archive or the CRRO examples to see the range of renderings. It’s the type of visual expertise I pride myself upon and continually seek to develop and refine.

I sat at my desk thinking, What do I need to know to talk about this iconography? How can I determine what the composition is likely to mean? What features are typical? What are unusual? Do comparanda exist for individual elements in the composition? Can they offer clues to support interpretations?

Whelp. I did it. Looked at every mirror in CSE and will do it again if I ever want to publish any of this. I took snapshots as I went of things that felt potentially relevant, but as so often I’d approach the survey of the evidence differently if I knew then what I know now. On my next pass I want to quantify (1) how many of each border type including nature of the border, intrusion of design over border, any lines defining the borders (2) number of figures in composition (3) nudity vs types of costume (4) depiction of landscape and/or interior space (5) animals depicted (6) facial hair (7) veiling (8) presence or absence of negative space (9) figures peeking over or around inanimate objects (10) genre of subject matter. All of that would allow me to be more absolute in the following observations, but as I didn’t count specifics I’m going to just narrate my general impressions of what I saw.

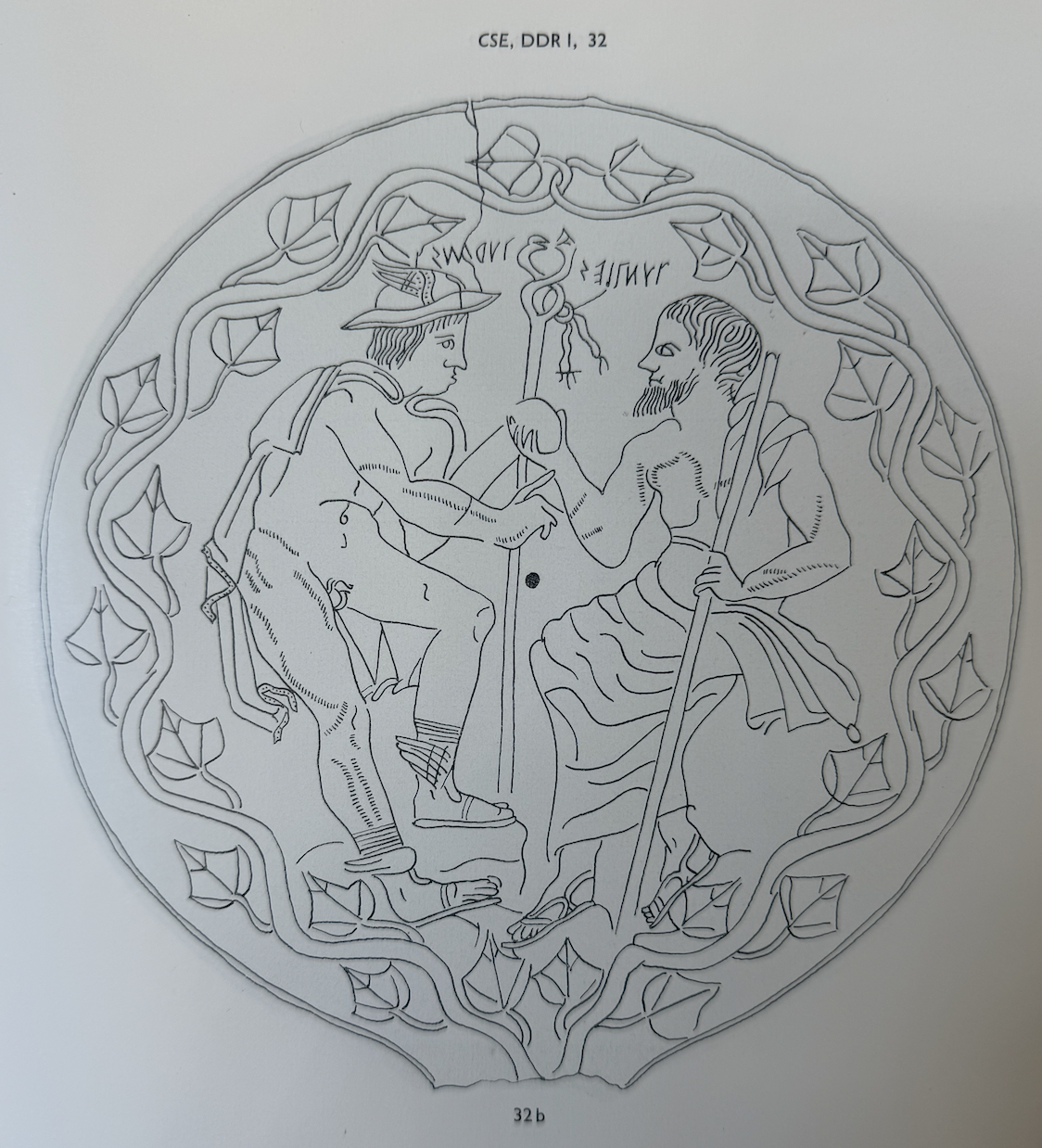

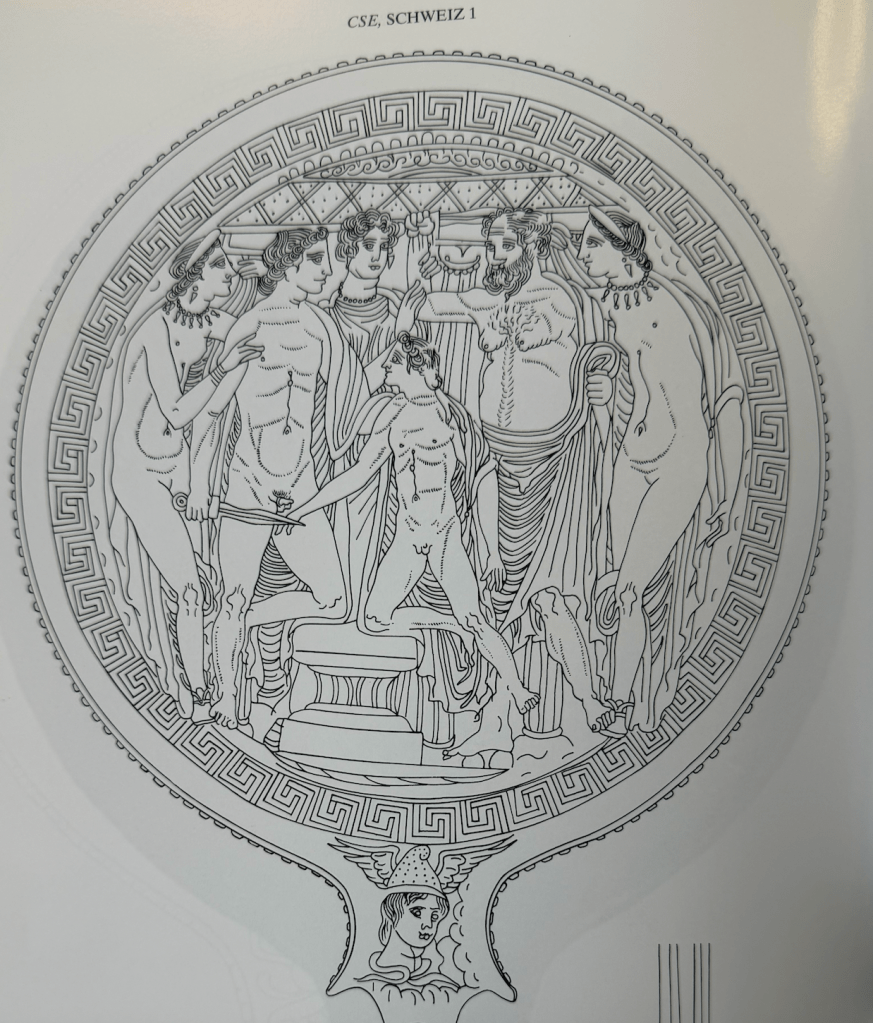

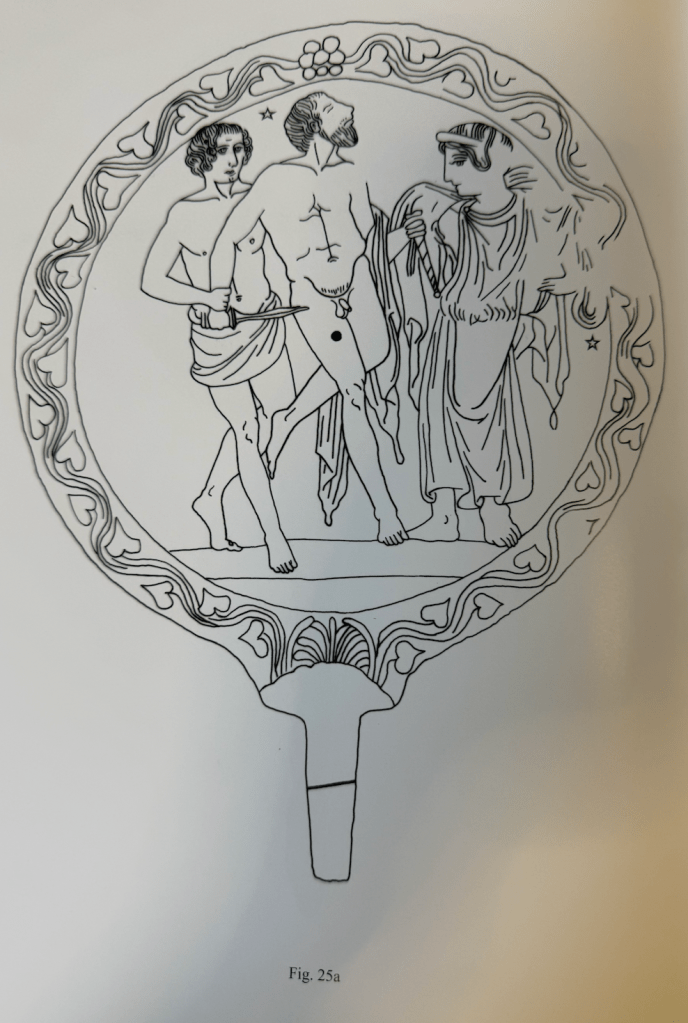

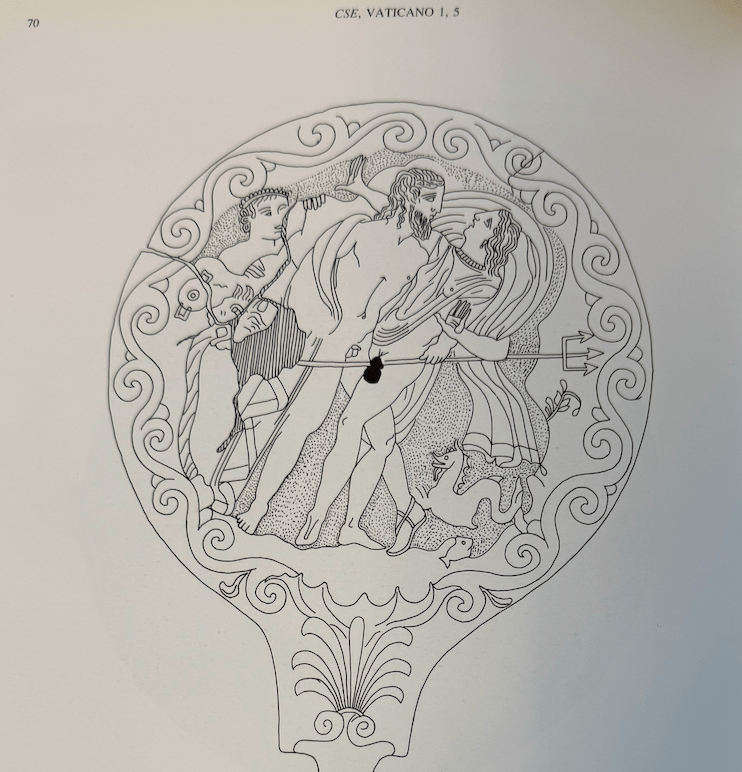

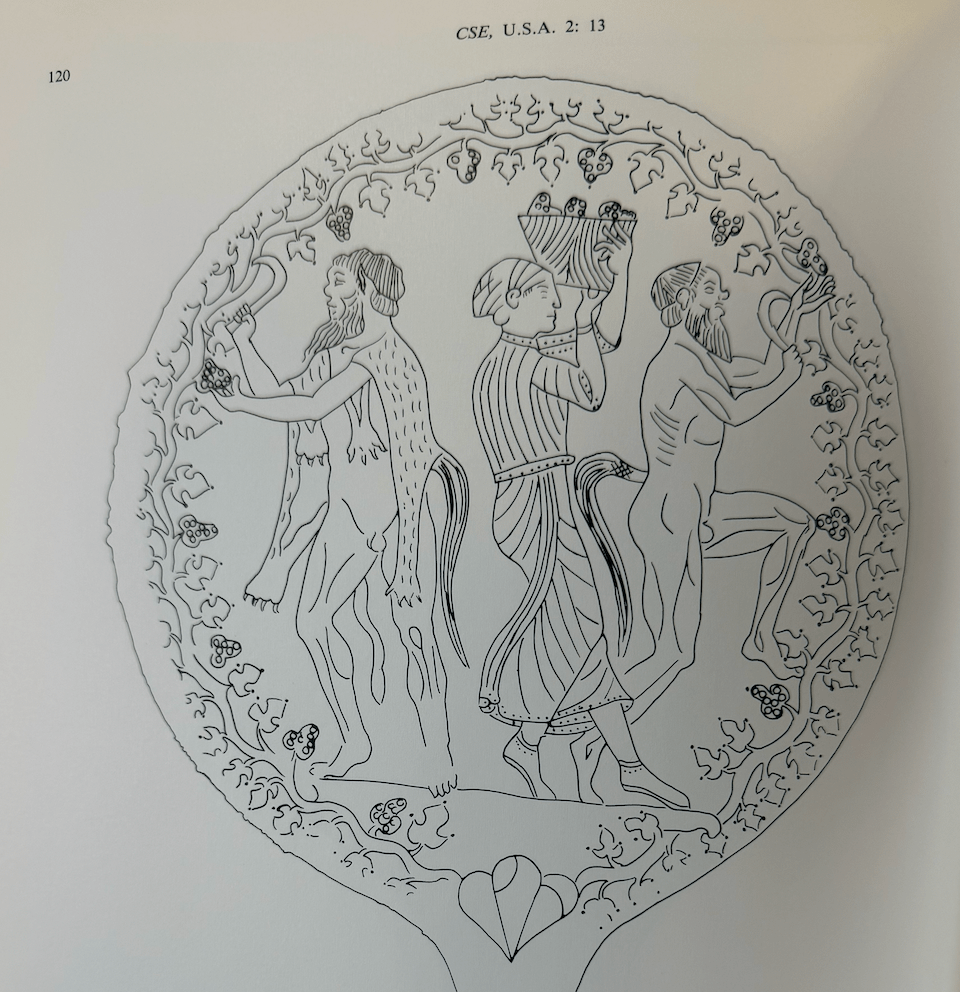

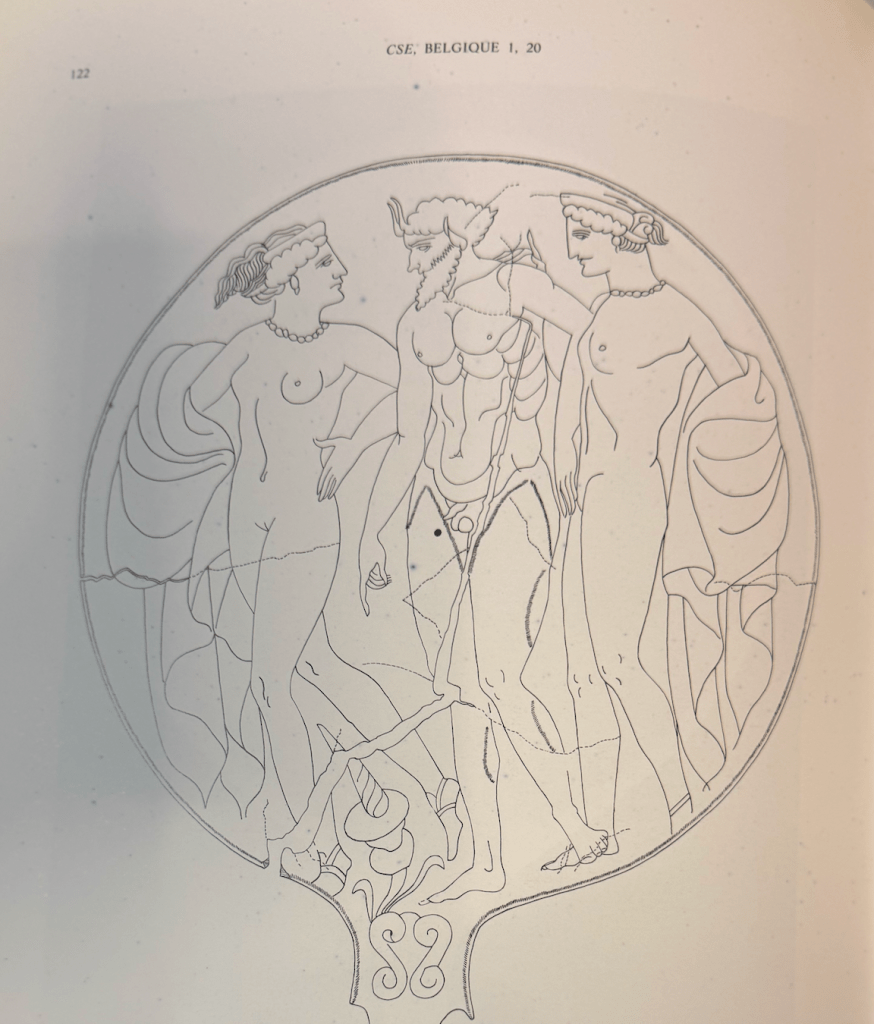

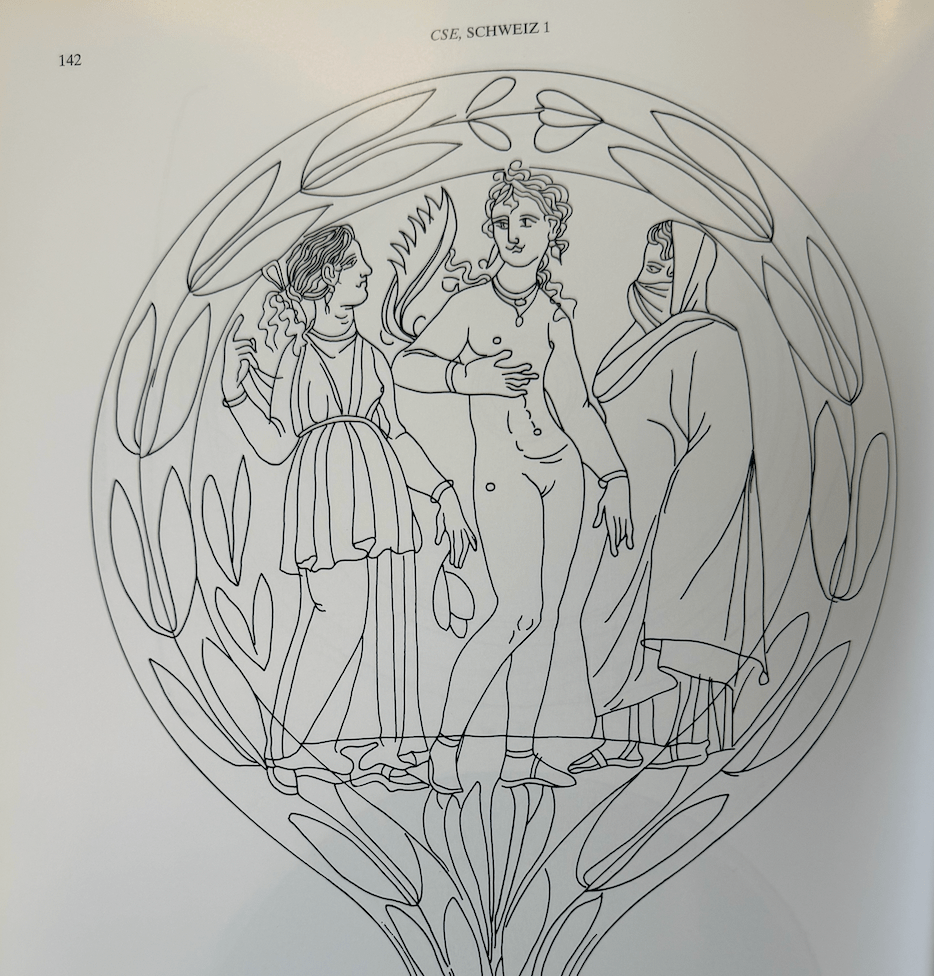

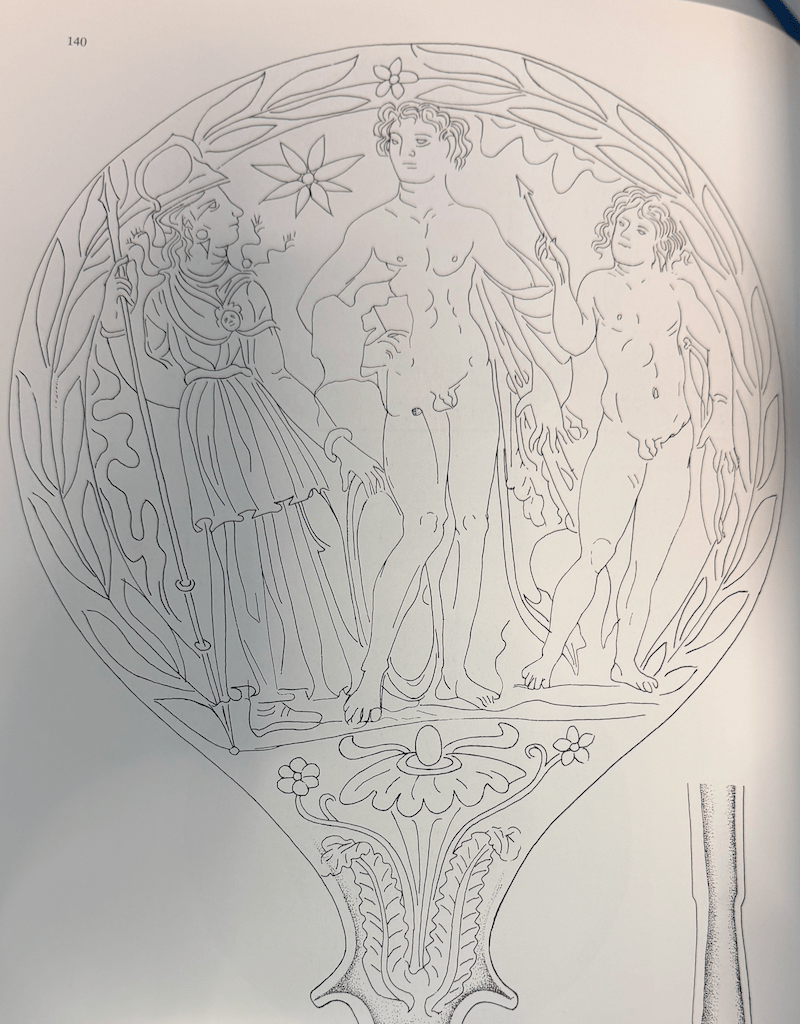

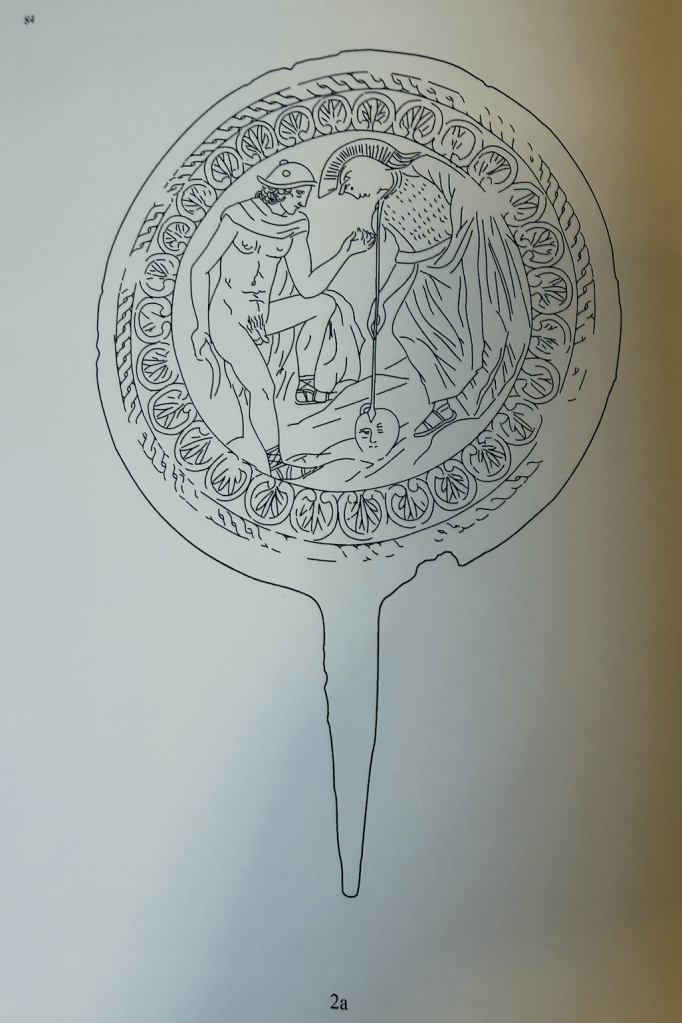

By far and away the most common composition is two figures with Phrygian caps and boot (often in knee length costume belted high on the chest) looking at each other typically with a star or dots between. After this most figural mirrors had either a two figure, three figure, or four figure compositional layout. Most figures stand but those closest to the outside of the design tend to curve/bend towards the more central space/figure(s). Reclining figures are rare. When four figures are present there is often a temple visible above their heads. Nudity is the most typical costume and the vast majority of figures are depicted as youthful. Facial hair is reserved for old men (kings?), a few wild men and paternal gods like Jupiter. Babies and Elders are rarely depicted. Animals rarely take up much of the compositional space excepting sometimes horses and the occasional hunting dog. When women are heavily draped their faces tend to be covered. The vast majority of subjects are drawn from what we might call Greek myth rather than Italic. Certain subjects repeat (Pelius and Thetis, Many Aphrodite scenes, Birth of Athena, Helen’s Egg, Hercules and Mercury).

All and all I’m left with the impression that the Bolsena mirror is bizarrely exceptional. I could find zero parallels for certain elements. That doesn’t mean they don’t exist, but it does mean they are unlikely to be common. I saw no bare trees. I saw no wolfs. I saw no lions that broke the fourth wall staring out at the viewer. I saw no women with fans or even fans as a compositional attribute in domestic ‘toilet’ scenes. I saw no figure in the same short tunic as the figure on the right hand of the composition.

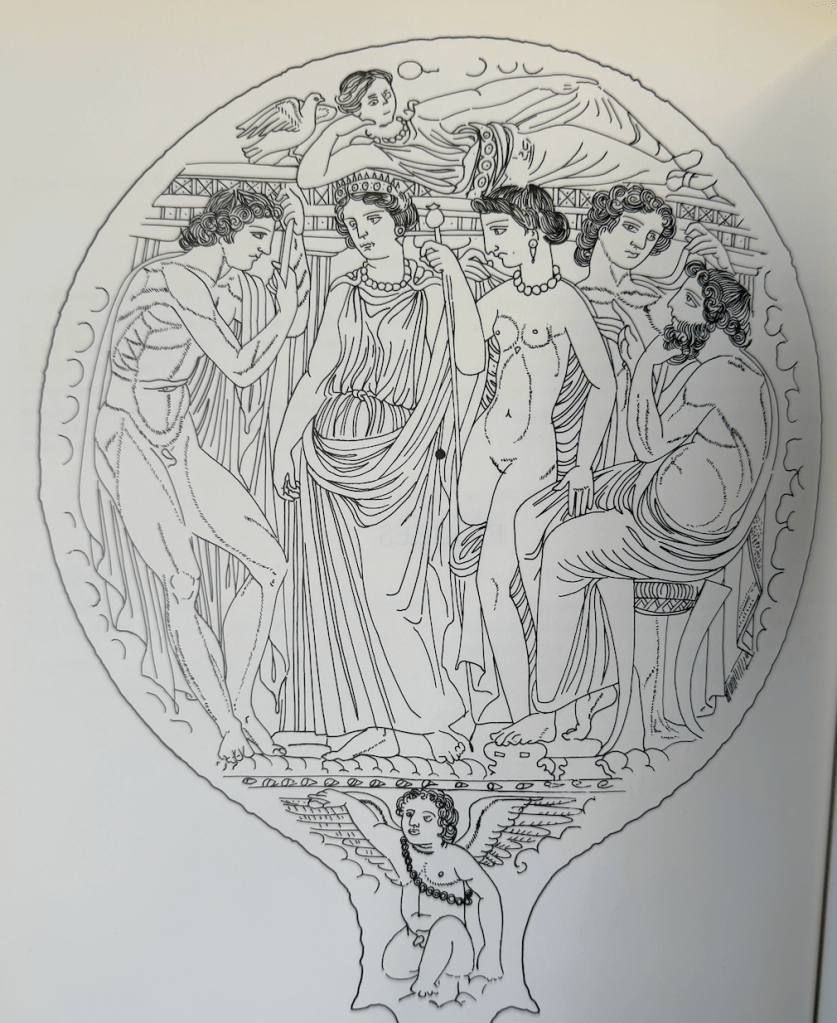

The Bolsena mirror feels familiar from my work on coins and intaglios, even lamps, but most mirrors do not feel this way. It is as if the vast majority of mirrors derive from a different stylistic approach to filling a circular compositional space. It also feels very Italic the same way much Etruscan tomb painting does but I’m thinking of especially the Tomba François or even some Bronze Cista (such as are associated with Praeneste, but also manufactured at Rome). Typically the Etruscan mirrors remind me more of the tondos of Kylixes if they connect to anything besides their own well-defined traditions.

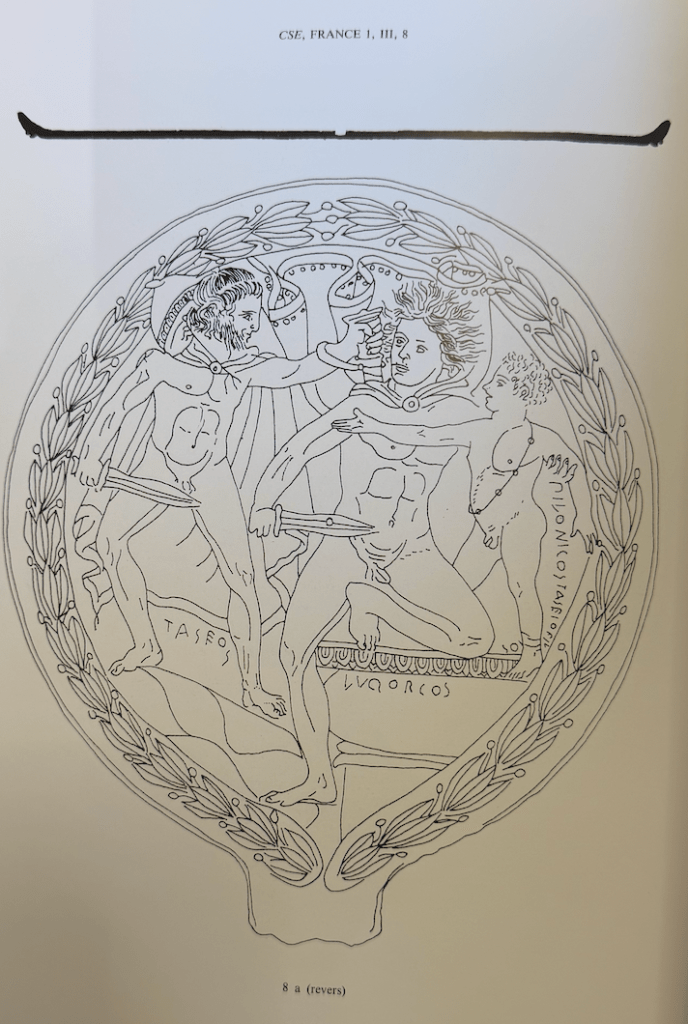

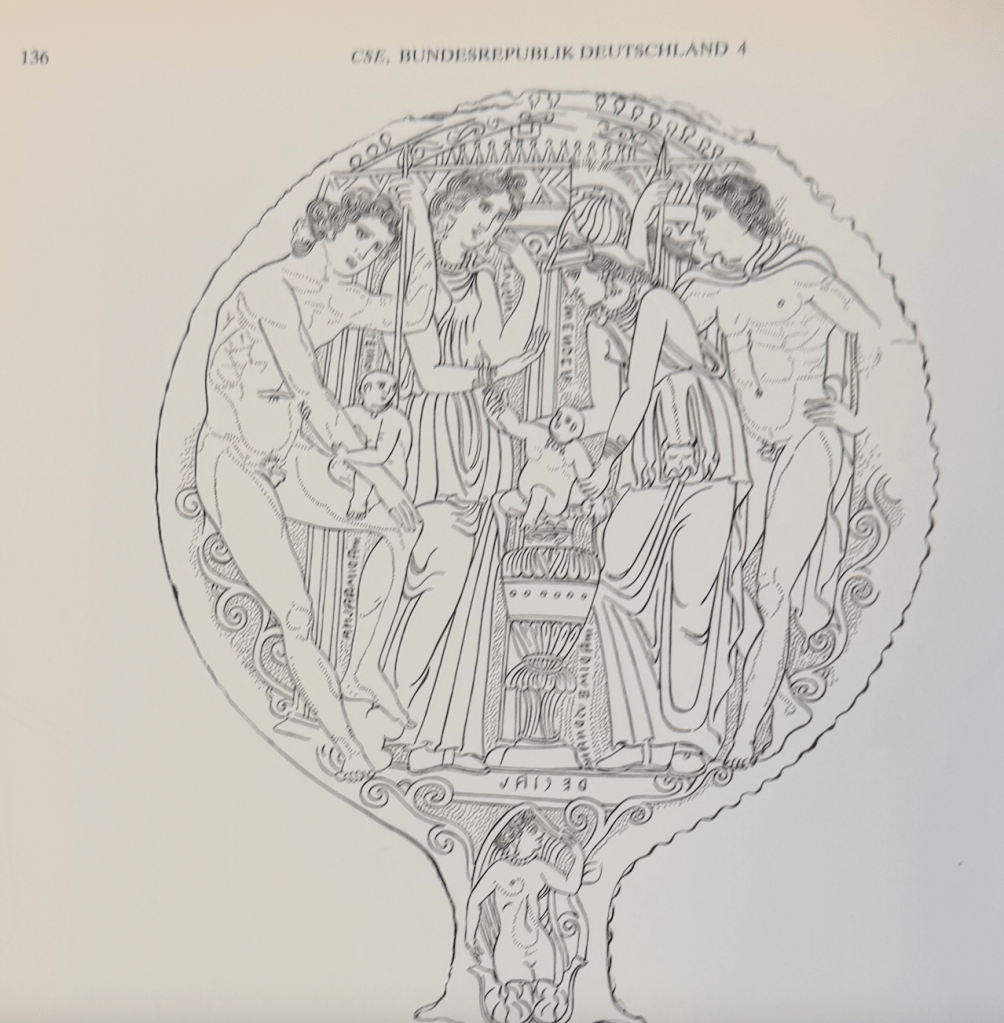

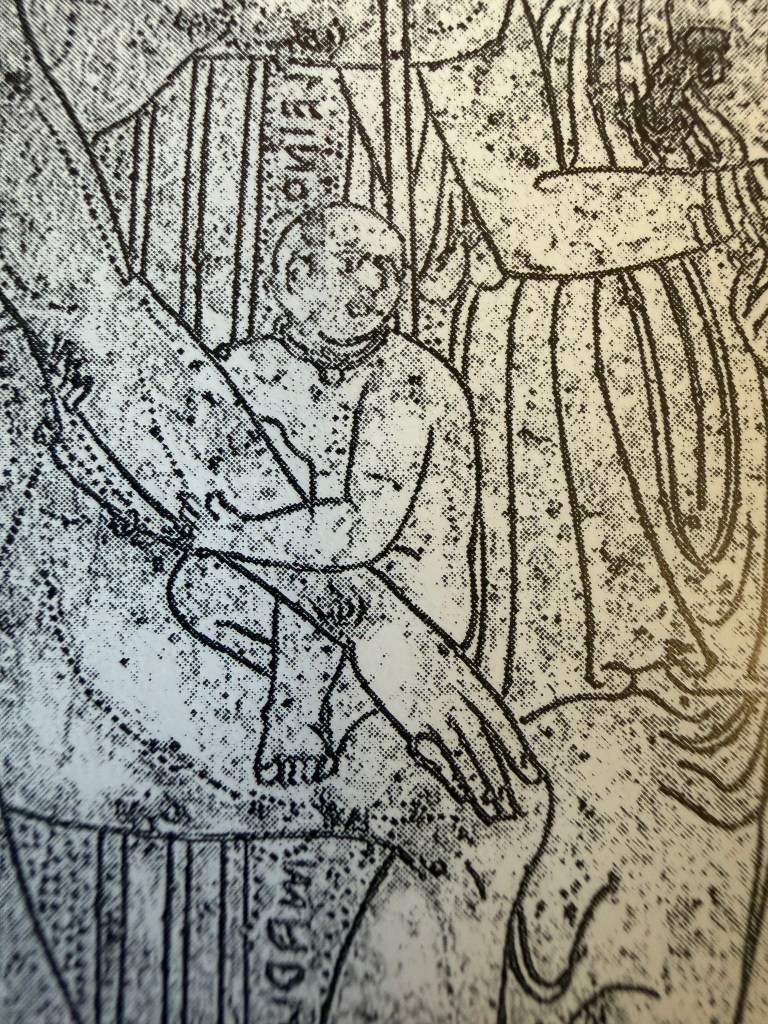

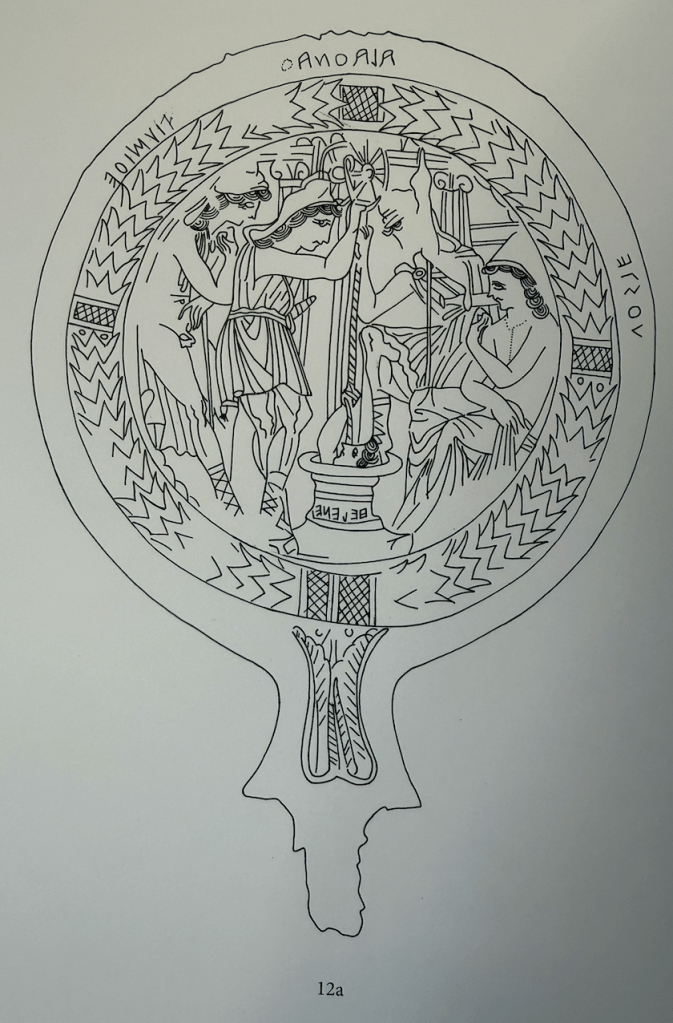

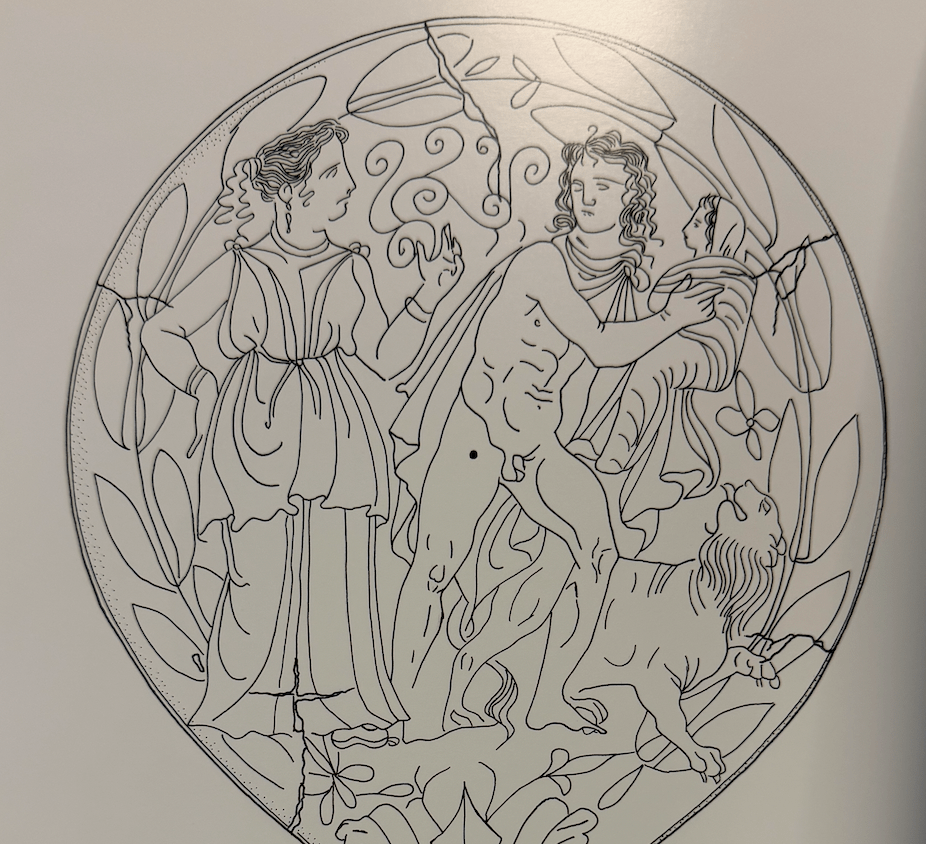

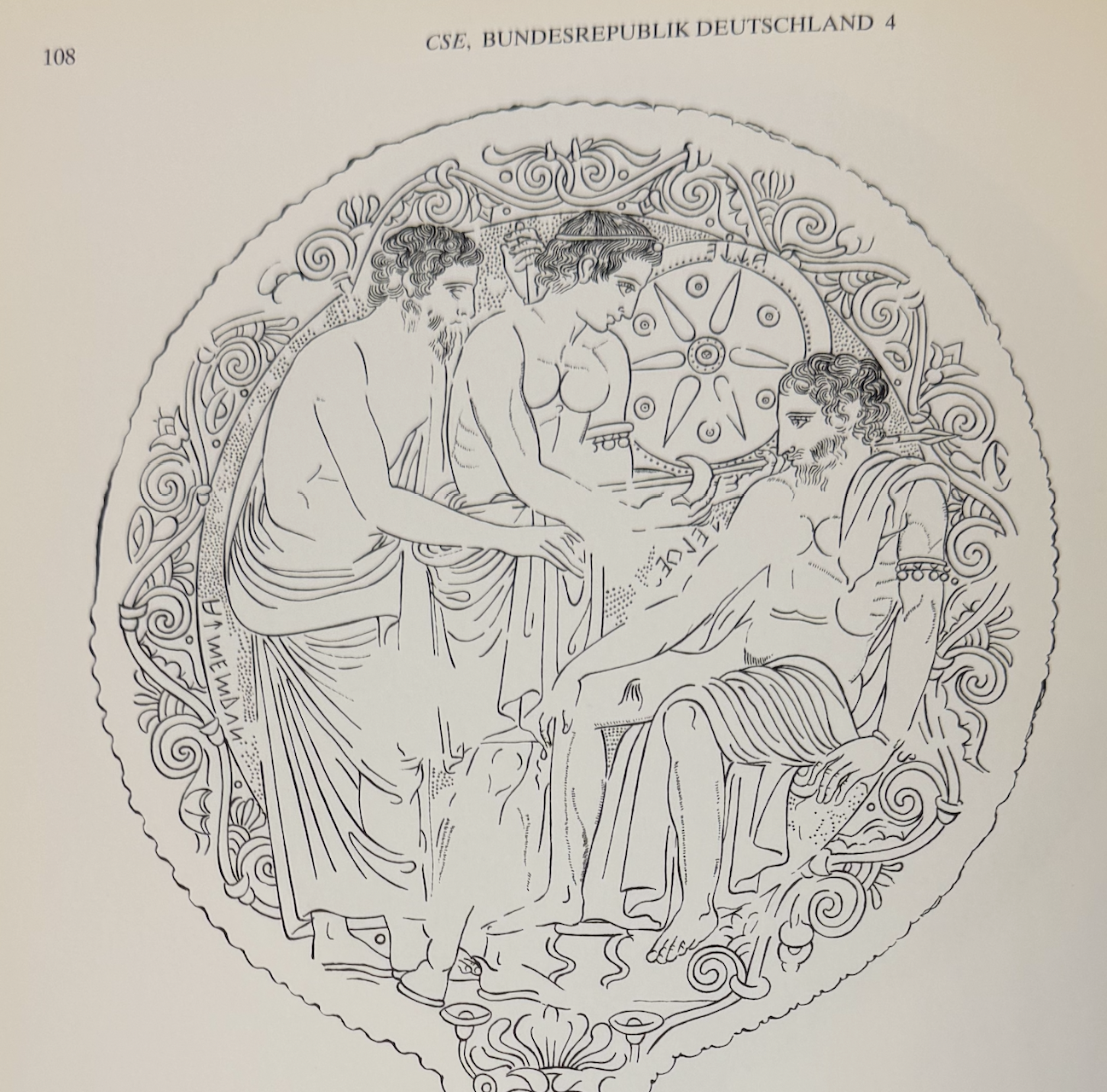

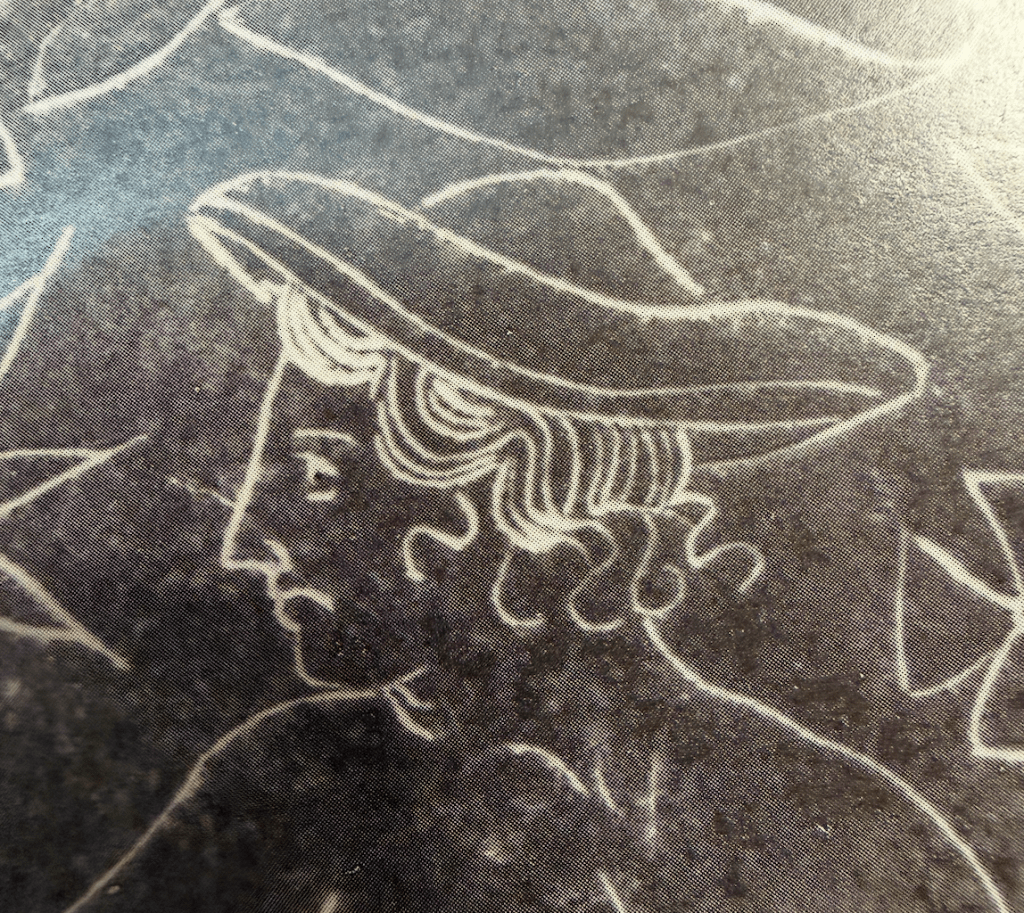

What follows are images I collected along my survey of CSE that I thought might be relevant. While there are a great deal of images here, I’m most struck by how none are a great parallel and that there really are not that many given the large number of images in the whole corpus. I don’t like arguments from silence and I don’t like trying to argue a negative conclusion, but the wolf and twins mirror is exceptional and really very different from other examples. I don’t know why and I don’t want to speculate, yet.

Next step, figure out bit more of how the Bolsena mirror came to light. So many of these mirrors don’t have secure find spots…

—

Later the same day.

So I’ve now tackled the publication that rehabilitated the mirror. I am glad I retained my habit of prioritizing my own investigation of the primary evidence prior to reading it through the lens of secondary scholarship.

I find myself not at all startled that the mirror had long been considered a fake and that it was only in 1982 that it was rehabilitated. The reading is adept and the images show clearly that the rendering of the certain details have strong parallels from mirrors associated with Praeneste. These details however are stylistic, rather than iconographic, comparisons. The Lion’s face is compared to that of Papa Silenus type figures, Mercury in 3/4 profile has strong parallels, one of which is a feminine face. The drapery of the right-hand figure, the so-called Quirinus figure, has parallels with drapery of a female figure. The centaur parallel offered for the face and hair of the left-hand figure (“Faunus”) is equally strong. I think the question remains:do these parallels amount to authentication? Praeneste is certainly a place where we know cista with more Italic themes were made. If the mirror is genuine, I would believe the attribution. It still gives me deep pause that there are so few parallels for iconographic similarities for similar figures, for all the stylistic comparisons seem potentially valid. I would really, really like to have this mirror sent for compositional analysis along side some of the stylistic parallels offered in the article or better yet some mirrors excavated more recently at Praeneste with secure context.

The mirror is said to have been sold to Alessandro Castellani in Florence in 1877, the Bolsena origin was part of the object origin story. No excavator. No more specific find details. As the Castellani Wikipedia page says

It has been hypothesized that some Etruscan finds traded by Castellani were fake.

The citations attached to this quotation:

Simpson, Elizabeth (2005). “Una perfetta imitazione del lavoro antico”, Gioielleria antica e adattamenti Castellani. In: I Castellani e l’oreficeria archeologica italiana. L’Erma di Bretschneider. pp. 177–200. ISBN88-8265-354-4.

Edilberto Formigli, Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer (1993). «Einige Faelschungen antiken Goldschmucks im 19. Jahrhundert», Archaeologischer Anzeiger (in German). pp. 299–332.

Here is a link to the forgeries he sold to the British Museum. Most came with so-called find spots.

If Castellani gave it away, rather than selling it, I wonder if he himself had doubts about it… There were few of his generation better able to judge genuine vs a good fake vs a bad fake. But this is only speculation. We need more data preferable metallurgical.

—

Reclining figure

Infants

—

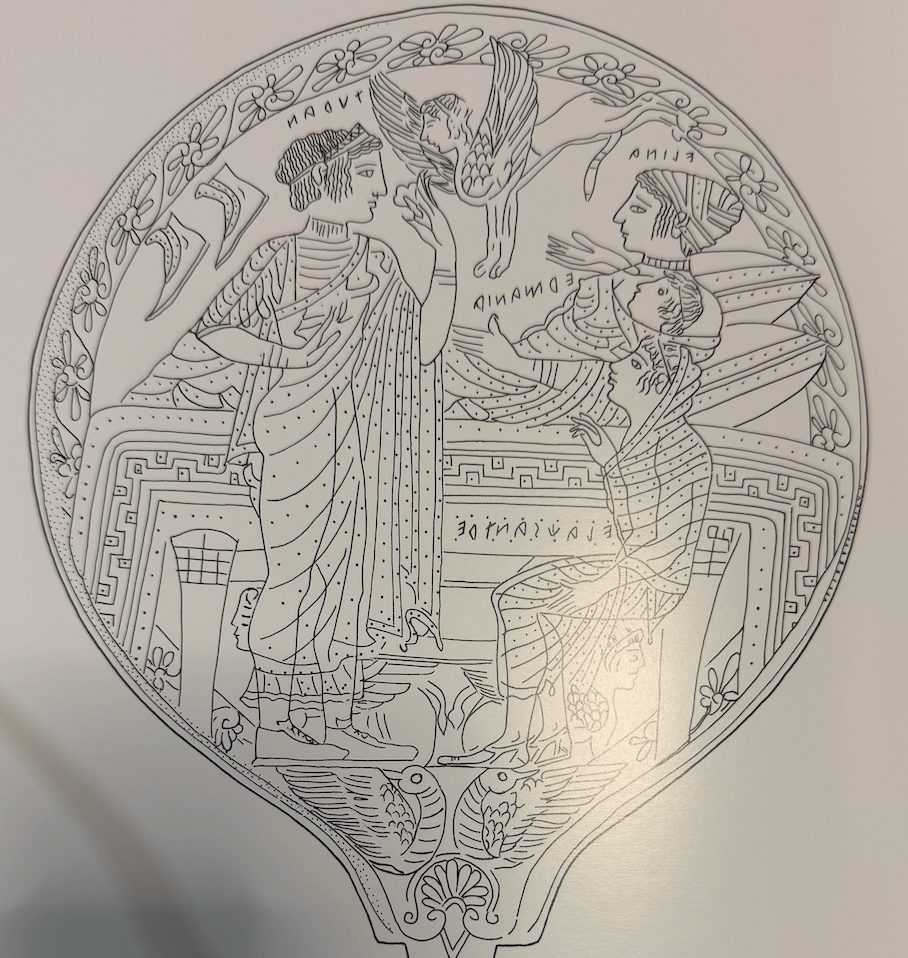

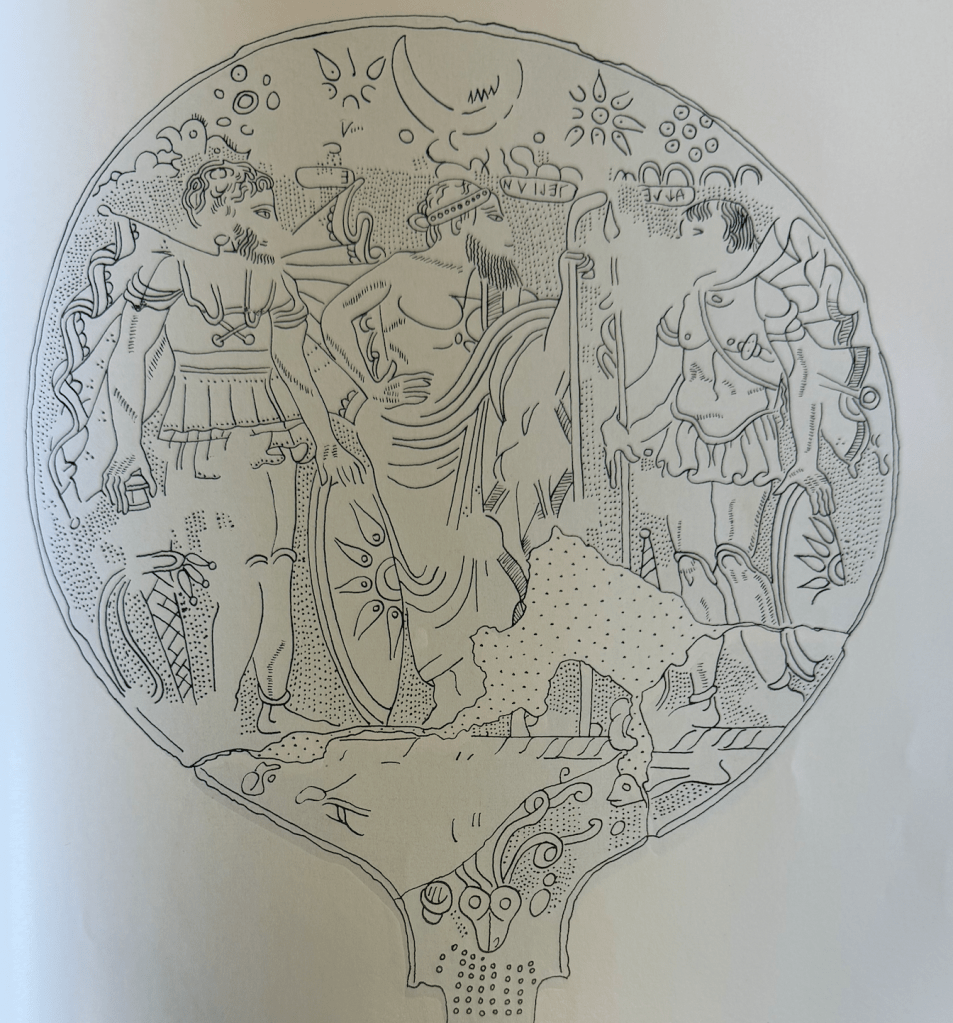

I don’t know why Helen is in a vase on the mirror to the right but given the motif of infants coming out of Vases I thought I’d include this one. Besides the mirror shown above there is a very similar one with three instead of two babies and then another cista with Mars coming out of a Vase. On the mirror to the right with Helen, the right hand figure is labeled Odysseus, the left hand Diomedes. The catalogue wanted ALAONAO to refer to owner of mirror, but shouldn’t it label the middle standing figure?

I find it fascinating that thus far it seems female infants are shown tightly wrapped while male infants are nude.

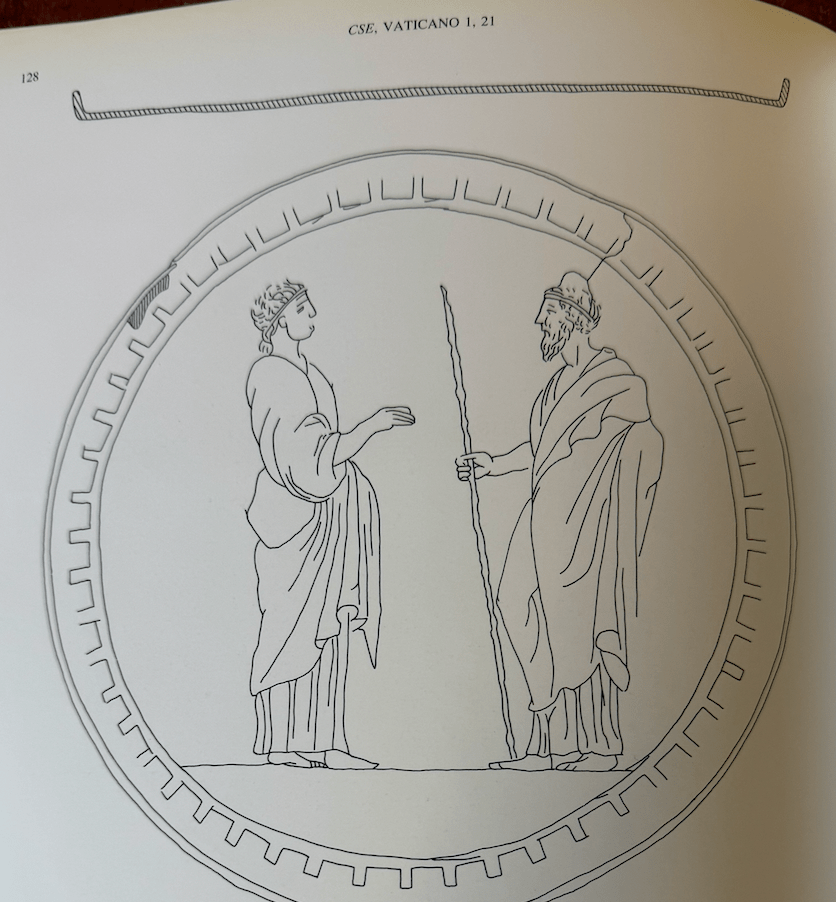

Beards

Notice that genitals are typically covered for bearded males unless they are gods or depicted enraged. They mostly have staves and bare chests with a toga like garment.

seated

standing

active

“wild” men

Veil

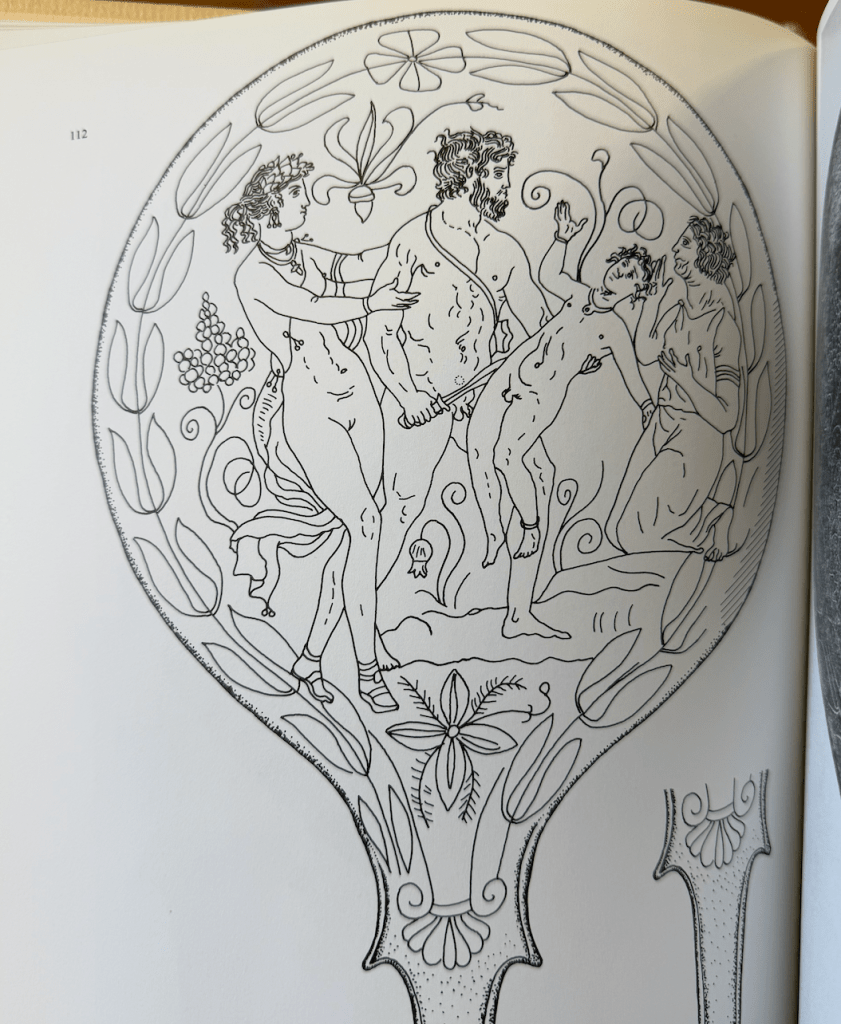

Floral motif

One of the only parts of the Bolsena wolf and twins mirror that feels deeply like other known mirrors is the ivy border growing out of a flower motif and the way the figures intrude into that border.

Wingless Travelling Hats

For other reasons, I’ve been reading on the very same mirrors! Basically I’m working my way backwards from scenes of divination, the head of Orpheus, and the like.

A few suggestions for further reading (I’ve got copies of most, if you can’t find them in the usual places). I completely agree that this is exactly the kind of thing that should be digital (should have been born digital really, but here we are):

Feel free to be in touch.

Thank you so much! I really appreciate ALL of this.