This is a pre writing piece associated with a publication goal and is thus part of the series that began with the punch marks post the other day.

I’m making my way through AVREVS.

It is a masterful collection of essays teasing out the historical relevance of the the results of the extensive Orleans project using LA-ICP-MS. The results of all this work is game-changing and has allowed us to interrogate, confirm and debunk many suppositions. So for instance the volume has shown that there is NOT a likely Ptolemaic origin for the mars/eagle gold one – a popular theory deriving from literary sources and iconographic parallels (see earlier post, more below as well). It inspries me to seek out similar opportunities for further metallurgical testing to secure even more answers (Can we confirm Pompey’s PRO COS aureus was made in Spain as Woytek has proposed?! Can we settle once and for all that the XXX oath scene goal is fake?!).

I’ve been dipping in and out of the AVREVS volume getting excited about various answers it provides, but now I want to think about it more holistically. Part of what I admire about the project is that it accepts that such work on metallurgical analyses must cross certain common boundaries. We must look at Greek, Roman, and Celtic coinages together as they share metal sources and relate to overlapping geographical areas. The more we try to separate them by rigged boundaries the harder this gets. So I’m reading mostly for an eye to the overlap. Hence that random post on Egyptian coins that went up last week.

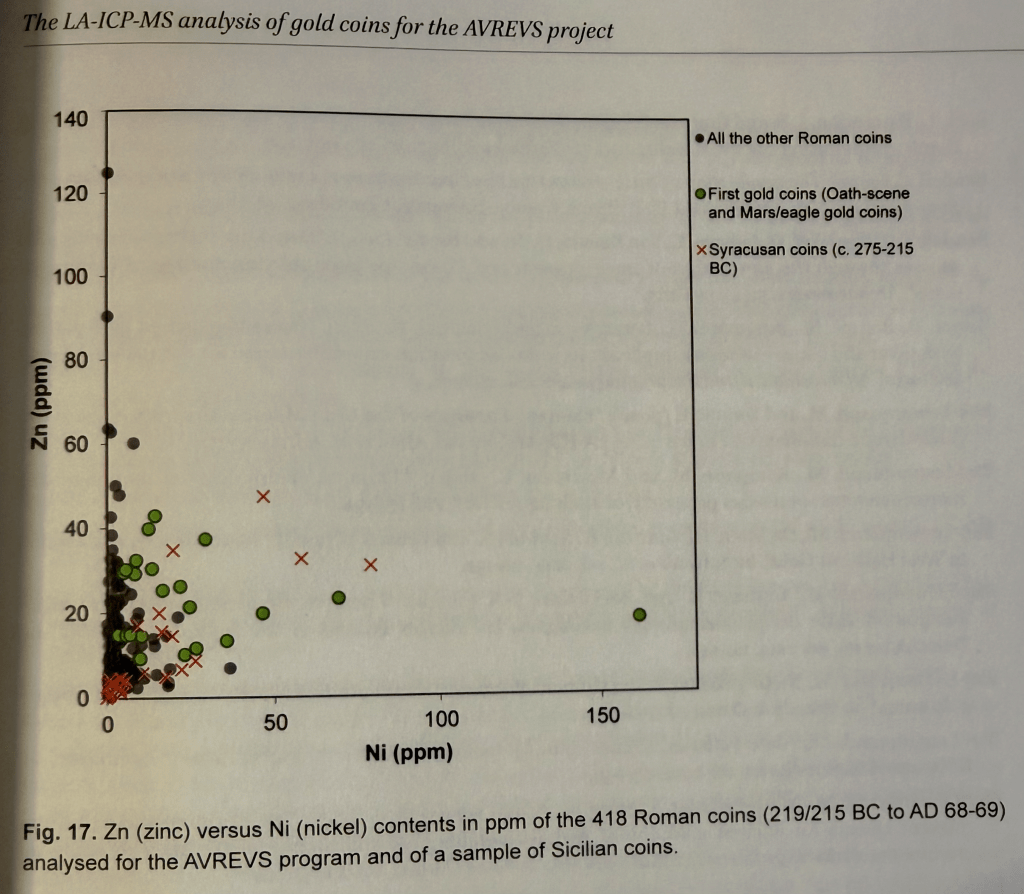

The basic methodology employed is to look for common patterns in the relative amounts of trace elements. This is not about finding the ore source, but rather about looking at what groups of coins have similar or different patterns and considering if those patterns are meaningful and why. In most cases Platinum to Palladium ratios are mapped, but other groups have also proved meaningful–Iron to Antimony, Antimony to Tin, and Zinc to Nickel. So below we quickly see that early Roman gold of the 2nd Punic war is very different than later Roman gold, but more similar to Syracusan gold. We know of many connections between Syracuse and Rome from our literary sources during the War but this is pretty convincing support (cf. Livy 22.37 – Hiero’s golden victory). If one studied Roman coins alone without reference to other mints we’d have a far poorer view of possible extensions.

As Fischer-Bossert (p.75) so aptly points out the Greek tradition of coinage has its origins in Mesopotamian hacksilber economy and that for most of its history was predominantly a silver coinage with gold being the exception, even if the origins of this coinage tradition itself beings in Lydia with ‘white gold’ or electrum. Although electrum (an alloy of silver and gold) does naturally occur, the electrum used for coinage was a controlled alloy even if different ratios are known. If we this line of thought to Italy and the early Romans we find ourselves back at silver becoming the dominant metal of coinage but having at its introduction to contend with indigenous traditions of using hunks of (leaded) bronze as monetary objects. The Italic peninsula is remarkably lacking in precious metal ores, these having to been imported. Thus the Romans and other Italic peoples accept silver, but gold remains much less common. We have 2nd Punic War gold, the Flaminius stater (made in Greece after 2nd Macedonian War), the Pompey stater (made in Spain during war against Sertorius), Sullan staters (mostly eastern, perhaps one made at Rome), and then the post 49 gold of the Civil Wars. It isn’t much and very little of it is produced at Rome after the 2nd Punic War. Fischer-Bossert (p. 84) gives a broad overview about who (before Alexander) minted gold and why (as far as we can surmise), but perhaps the most important point he makes is this ….

What marks out the Roman imperial coinage from the republic is that gold is produced on a very regular basis, something that was exceptional under the republic.

I’m going to have more to say but I think I’ll stop this post here and move on to a new one.

One thought on “Greek, Hellenistic, Republican… Where are the lines?”