To be updated periodically

Advice to Those Starting Graduate School

Mostly targets at those at elite humanities programs in the US

adventures in my head

To be updated periodically

Mostly targets at those at elite humanities programs in the US

Cato’s own words, as follows: “And I really think that the Rhodians did not wish us to end the war as we did, with a victory over king Perses. But it was not the Rhodians alone who had that feeling, but I believe that many peoples and many nations agreed with them. And I am inclined to think that some of them did not wish us success, not in order that we might be disgraced, but because they feared that if there were no one of whom we stood in dread, we would do whatever we chose. I think, then, that it was with an eye to their own freedom that they held that opinion, in order not to be under our sole dominion and enslaved to us. But for all that, the Rhodians never publicly aided Perses. Reflect how much more cautiously we deal with one another as individuals. For each one of us, if he thinks that anything is being done contrary to his interests, strives with might and main to prevent it; but they in spite of all permitted this very thing to happen.”

I want to think about this more in future as it relates Polybius’ project in extending his histories by 10 books and in the debates over the destruction of Carthage found in other authors…

Derow taught not to talk of Rome (at least so far as Polybius’ Bk 6 goes) of a mixed constitution (a little of this, a little of that), but instead as balanced. He didn’t mean this so much as checks and balances but more the balancing act of not letting the anacyclosis (the cycle of constitutions) role on to the next form: monarchy to tyranny to aristocracy to oligarchy to democracy to ochlocracy. Rome was (precariously) balanced: the wheel wasn’t rolling (yet).

That’s background (and how I teach the republican government a la Polybius most semesters).

This blog post is because I just read again a sentence from the Cicero’s Republic (2.42):

For those elements which I have mentioned were combined (mixta) in our State as it was then, and in those of the Spartans and Carthaginians, in such a way that there was no balance (temperata) whatever.

I’ve never thought my views (via Derow’s) of aligned with those of Cicero’s…

Papius again. You might also notice I let my obsession run a little wild last night after the kids went to bed and got started on my typology.

Or would I say forge or kiln? I better look up some obscure Latin if I’m going to continue worrying about the identity of objects on the Papius series (j/k). Anyway this is relevant to ancient technologies around metal refinement and thus would be familiar to those engaged in mint operations.

If this is really Crawford symbol 24 like the catalogue suggests, than the drawings (or they specimens they were based on) were poor indeed.

Update 10-25-21:

Definitely a forger’s die. (or a modern forgery of such an object) Most likely created using hubbing. This is made obvious by comparison with specimens in the Schaefer Archive. A huge shame current location and details of discovery of this unique object are not known.

Original Post:

The idea of a real republican die for the main mint surviving seems completely improbable. I just can’t make up a story whereby this would happen. This must be an imitation, but a nice one… Hubbed? There are imitations known but not this fine (and another example). Just reacting. But the control mark isn’t one detailed by Crawford 1974: p. LXVIII-LXIX (not that those sketches are perfect, but their usually pretty good). The rightly catalogue says: “Für das Symbol vgl. 148.” But this clearly isn’t Crawford’s 148 as that is a pair of animal heads. There is a small chance that it matches Crawford’s 86: a lamp hook and a lamp. Helps if I look at the right plates…. Strangely the odd symbol makes me think it is more genuine. Hmm.. Must think more: Papius is on my list of future projects.

(in the Princeton museum)

The sort of object needed to hang up one of these (or as Crawford says, a cooking pot):

Cic. de re pub

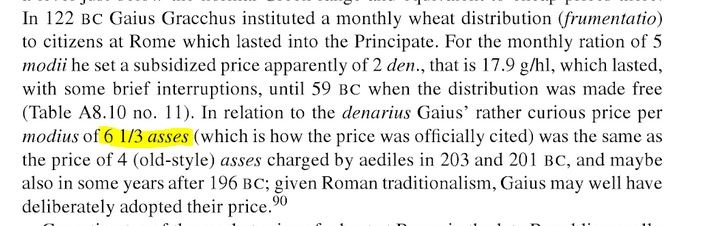

By ‘old-style’ what Rathbone and von Reden mean here is what 1/5 of two denarii would have been before the retariffing of the denarius from 10 asses to 16 asses. This is a simple and brilliant explanation of Gaius Gracchus’ otherwise bonkers pricing structure. And the first good illustration I’ve seen of how Romans reacted to the retariffing.

This is just fun.

C. 101 (Mattingly) or 104 (Crawford) this novus homo makes a VERY conservative coin (RRC 318/1) (gorgeous specimen though!):

By 94 he’s consul. And Cicero’s brother is using him as a positive exempla by the late 60s:

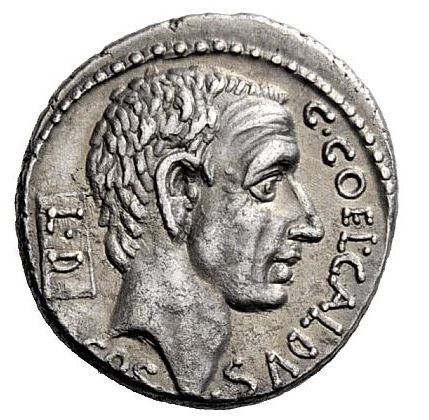

Then his son (so Crawford, I think perhaps grandson — we don’t know the moneyer’s filiation I don’t think, but I need to go through Cicero’s letters again to double check) in 51 BCE puts his portrait on a coin (RRC 437):

I don’t think we have any other portraits of moneyers except Brutus… And none where the portrait is from the regular coin series. That’s your trivial detail for the day.

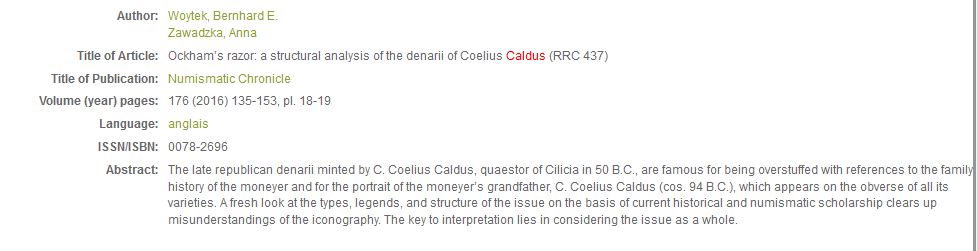

I guess I had good instincts on the grandson thing… I’ve ordered this via ILL and will update blog as I read more:

Woytek, Bernhard E. and Zawadzka, Anna. “Ockham’s razor: a structural analysis of the denarii of Coelius Caldus (RRC 437).” Numismatic Chronicle 176 (2016): 135-153.

Responding to all this:

Ryan, Francis Xavier. “Die Legende IMP.AV.X auf den Denaren des Triumvirn Caldus.” Schweizer Münzblätter = Gazette Numismatique Suisse 56, no. 222 (2006): 39-42. Doi: 10.5169/seals-171948

Badian, Ernst. “Two numismatic phantoms: the false priest and the spurious son.” Arctos 32 (1998): 45-60.

Evans, Richard J.. “The denarius issue of CALDVS IIIVIR and associated problems.” The Ancient History Bulletin V (1991): 129-134.