Macrobius Saturnalia 1.17.25-30:

Sextus Pompeius Festus, De Verborum Significatione 326.52

“Salva res est dum cantat senex”, quare parasiti Apollonis in scaena dictitent, causam Verrius in lib. V, quorum prima est p littera, reddidit, quod C. Sulpicio, C. Fulvio cos., M. Calpurnio Pisone praetore urb. faciente ludos, subito ad arma exierint, nuntiatio adventus hostium, victoresque in theatrum redierint solliciti, ne intermissi religionem adferrent, instaurati qui essent: inventum esse ibi C. Pomponium, libertinum mimum magno natu, qui ad tibicinem saltaret. Itaque gaudio non interruptae religionis editam vocem nunc quoque celebrari. At in hoc libro refert Sinni Capitonis verba, quibus eos ludos Apollinares Claudio et Fulvio cos. factos dicit ex libris Sibyllinis et vaticinio Marci vatis institutos, nec nominatur ullus Pomponius. Ridiculeque de ipsa appellatione parasitorum Apollinis hic causam reddit, cum in eo praeterisset. Ait enim ita appellari, quod C. Volumnius, qui ad tibicinem saltarit, secundarum partium fuerit, qui fere omnibus mimis parasitus inducatur. Quam inconstantiam Verrii nostri non sine rubore rettuli.

This passage seem to correspond to a tradition of an interruption at the games as mentioned by Macrobius above. It also seems to engage in a debate about the role of Pomponii in the festival. Servius also knows this story!

Maurus Servius Honoratus, In Vergilii Aeneidos Libros 3.274

avdax qvos rvmpere pallas sacra vetat ne interruptione sacrificii— ‘rumpere’ enim pro ‘interrumpere’ posuit—piaculum committeretur: unde etiam Helenus “nequa inter sanctos ignes in ho- nore deorum hostilis facies occurrat et omina turbet”. denique cum ludi circenses Apollini celebrarentur et Hannibal nuntiatus esset circa portam Collinam urbi ingruere, omnes raptis armis concurrerunt. reversi postea cum piaculum formidarent, invenerunt saltantem in circo senem quendam. qui cum interrogatus dixisset se non interrupisse saltationem, dictum est hoc proverbium ‘salva res est, saltat senex’. ‘audacem’ autem dicit ubique Vergilius, quotiens vult ostendere virtutem sine fortuna: unde etiam Turnum audacem vocat.

APOLLINARES LUDI, games in honor of Apollo; the people witnessed the spectacle crowned with laurels, and each paid according to his means.

Varro LL 6.18 (Loeb adapted)

The Nones of July are called the Caprotine Nones, because on this day, in Latium, the women offer sacrifice to Juno Caprotina, which they do under a caprificus ‘wild fig-tree’; they use a branch from the fig-tree. Why this was done, a historically themed play presented to them at the Games of Apollo enlightened the people.

Nonae Caprotinae, quod eo die in Latio Iunoni Caprotinae mulieres sacrificant et sub caprifico faciunt; e caprifico adhibent virgam. Cur hoc, togata praetexta data eis Apollinaribus Ludis docuit populum.

See Cirilo de Melo trans and commentary for reasons for necessary adaptation. Cf. Mac. Sat. 1.11.36-39 for summary of events that likely represent the plot of the play. Also cf. also Plut. Rom. 29.4 and Cam. 33.3. – I’d like one day to write an article about the loyal slave gets freedom trope in togata praetexta (historical plays) at a foot note to Richlin’s work on Plautus.

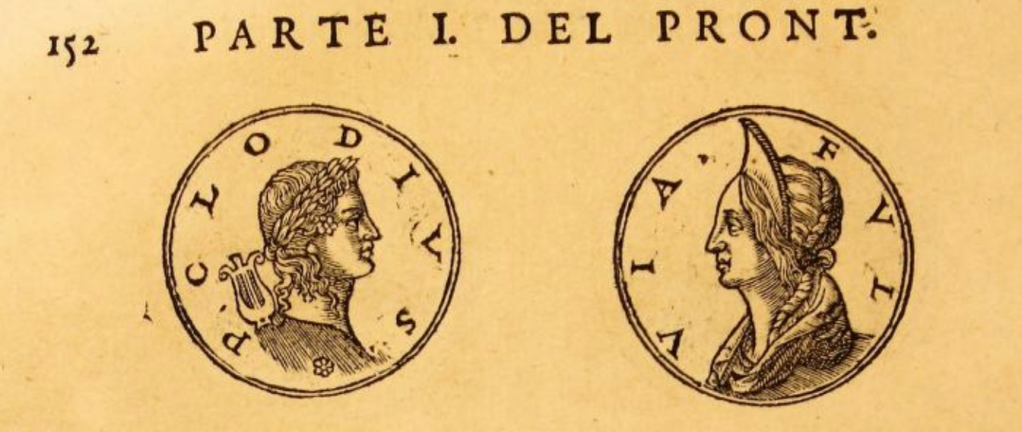

Val Max 6.2.9 (S-B loeb trans; 59 BCE cf. Cic. Att. 2.19.3)

Diphilus tragoedus, cum Apollinaribus ludis inter actum ad eum versum venisset in quo haec sententia continetur ‘miseria nostra magnus es,’ derectis in Pompeium Magnum manibus pronuntiavit, revocatusque aliquotiens a populo sine ulla cunctatione nimiae illum et intolerabilis potentiae reum gestu perseveranter egit. eadem petulantia usus est in ea quoque parte ‘virtutem istam veniet tempus cum graviter gemes.’

Cicero gives “nostra miseria tu es magnus” and as S-B notes in commentary, Pompey was not in the theatre but in Capua.

Plin NH 19.23 (Loeb)

Tenting were used to make shade in the theatres, something first instituted by Quintus Catulus when dedicating the Capitol. Next Lentulus Spinther is recorded to have been the first to stretch awnings of linen in the theatre, at the games of Apollo. Soon afterwards Caesar when dictator stretched awnings over the whole of the Roman Forum, as well as the Sacred Way from his mansion, and the slope right up to the Capitol, a display recorded to have been thought more wonderful even than the show of gladiators which he gave.

In theatris tenta umbram fecere, quod primus omnium invenit Q. Catulus cum Capitolium dedicaret. carbasina deinde vela primus in theatro duxisse traditur Lentulus Spinther Apollinaribus ludis. mox Caesar dictator totum forum Romanum intexit viamque sacram ab domo sua et clivum usque in Capitolium, quod munere ipso gladiatorio mirabilius visum tradunt.

Cic. Phil. 1.36 (regarding pro Brutus anti Antony sentiment in 44; cf. Phil 2.31, 10.8)

And then there was the applause at the Apollinarian games, or rather the people’s testimony and expression of their feelings. Did you find that insufficient?

Apollinarium ludorum plausus vel testimonia potius et iudicia populi Romani parum magna vobis videbantur?

On political demonstrations also Cic. Vat. 115-127. Not explicitly Games of Apollo but most think refers to events at them.

Cic. Att. 16.4.1

I went to Nesis on the 8th. Brutus was there. How distressed he was about the ‘Nones of July’—quite extraordinarily upset! So he said he would write instructing them to announce the Hunt which takes place on the day following the Games of Apollo for the ‘14th Quintilis.’

Dio 48.20

However, when Sextus learned of this, he waited until Agrippa was busy with the Ludi Apollinares; for he was praetor at the time, and was not only giving himself airs in various other ways on the strength of his being an intimate friend of Caesar, but also in particular gave a two-days’ celebration of the Circensian games and prided himself upon his production of the game called “Troy,” which was performed by the boys of the nobility. Now while he was thus occupied, Sextus crossed over into Italy and remained there…

Dio 47.18-19

And they compelled everybody to celebrate his birthday by wearing laurel and by merry-making, passing a law that those who neglected these observances should be accursed in the sight of Jupiter and of Caesar himself, and, in the case of senators or senators’ sons, that they should forfeit a million sesterces. Now it happened that the Ludi Apollinares fell on the same day, and they therefore voted that his birthday feast should be celebrated on the previous day, on the ground that there was an oracle of the Sibyl which forbade the holding of a festival on Apollo’s day to any god except Apollo. Besides granting him these honours, they made the day on which he had been murdered, a day on which there had always been a regular meeting of the senate, an unlucky day.

Dio 43.48, 45 BCE

The administration of the finances, after being diverted at this time for the reasons I have mentioned, was no longer invariably assigned to the quaestors, but was finally assigned to ex-praetors. Two of the city prefects then managed the public treasuries, and one of them celebrated the Ludi Apollinares at Caesar’s cost.

Dio 48.33, 40 BCE (perhaps 41?)

In the year preceding this, men belonging to the order of knights had slaughtered wild beasts at the games in the Circus on the occasion of the Ludi Apollinares, and an intercalary day had been inserted, contrary to the rule, in order that the first day of the succeeding year should not coincide with the market held every nine days—a clash which had always been strictly guarded against from very early times.

Dio 47.20

And yet Cassius was praetor urbanus and had not yet celebrated the Ludi Apollinares. But, although absent, he performed that duty most brilliantly through his colleague Antony; he did not himself sail away from Italy at once, however, but lingered with Brutus in Campania and watched the course of events. And in their capacity as praetors they kept sending letters to the people at Rome…

Something seems to have gone wrong here and Cassius and Brutus should be reversed in this passage to match other testimony

Plin. NH 35.100

Boy in the Temple of Apollo, a picture of which the beauty has perished owing to the lack of skill of a painter commissioned by Marcus Junius as praetor to clean it in readiness for the festival of the Games of Apollo.

Cic. Brut. 78

Now by this time a richer and more brilliant habit of speaking had arisen; for when Gallus as praetor conducted the games in honour of Apollo, Ennius at that festival presented the tragedy of Thyestes, and died in the year of the consuls Quintus Marcius and Gnaeus Servilius.

Serv. Virg. Aen. 6.70

festosqve dies de nomine phoebi ludos Apollinares dicit, qui secundum quosdam bello Punico secundo instituti sunt, secundum alios tempore Syllano ex responso Marciorum fratrum, quorum extabant, ut Sibyllina, responsa.

Vitruvius 7. pr. 4

Possible inspiration or parallel for Roman games.