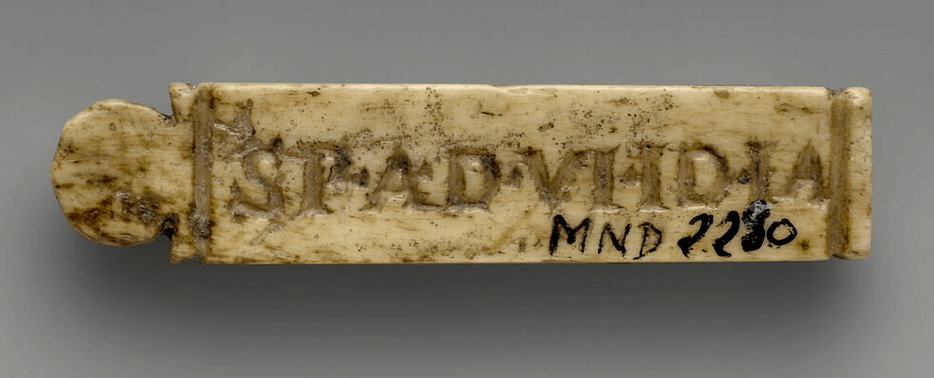

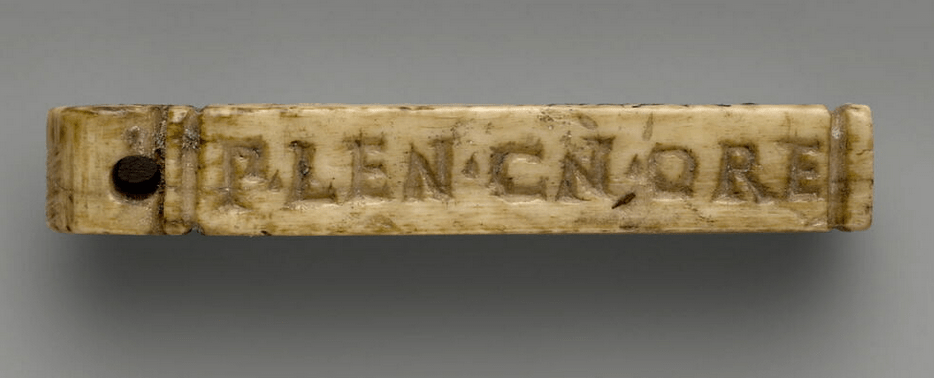

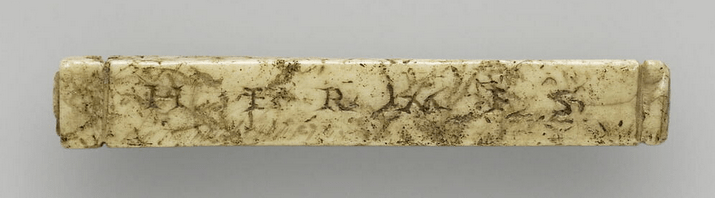

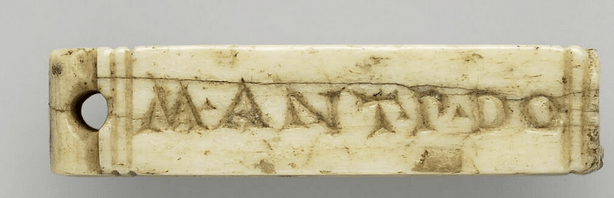

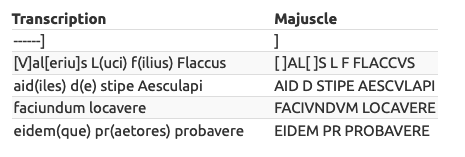

I’m cheating on my extensive administrative responsibilities and teaching duties because my brain is obsessed with these tessera nummularia (see previous post to watch the development of my interest from a few random specimens in the louvre to an all out compulsion)

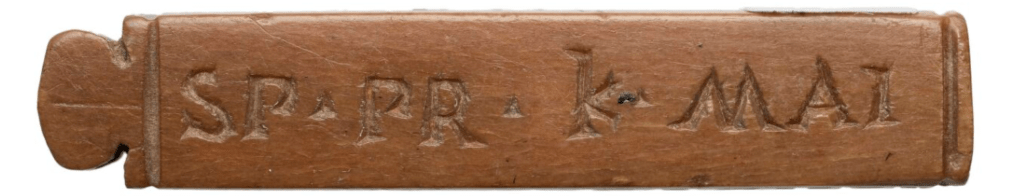

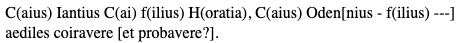

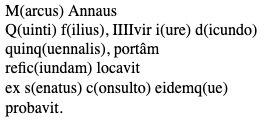

In many ways this is the most important one:

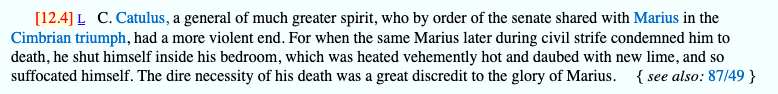

“Anchialus, enslaved by Lucius Sirtus, inspected the coins [for] the month of February, in the consulship of Marcus Tullius [Cicero!] and Gaius Antonius”

This is the only one out of the whole corpus to mention what is being inspected but it confirms the current predominant scholarly interpretation today that these objects were used to regulate coins in some way.

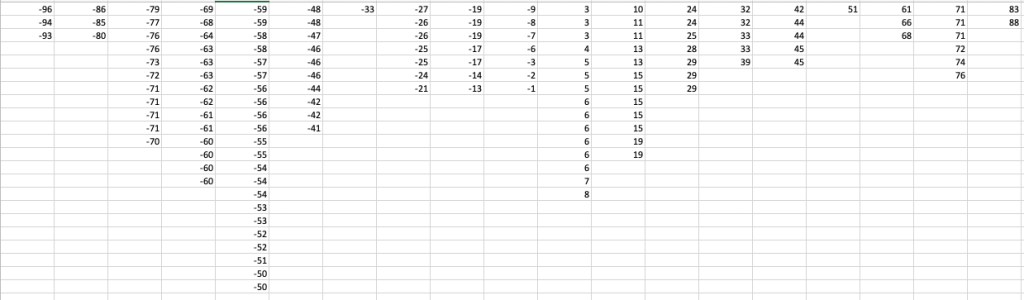

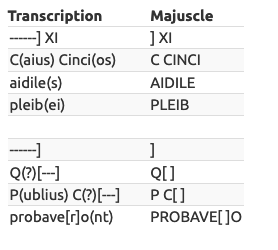

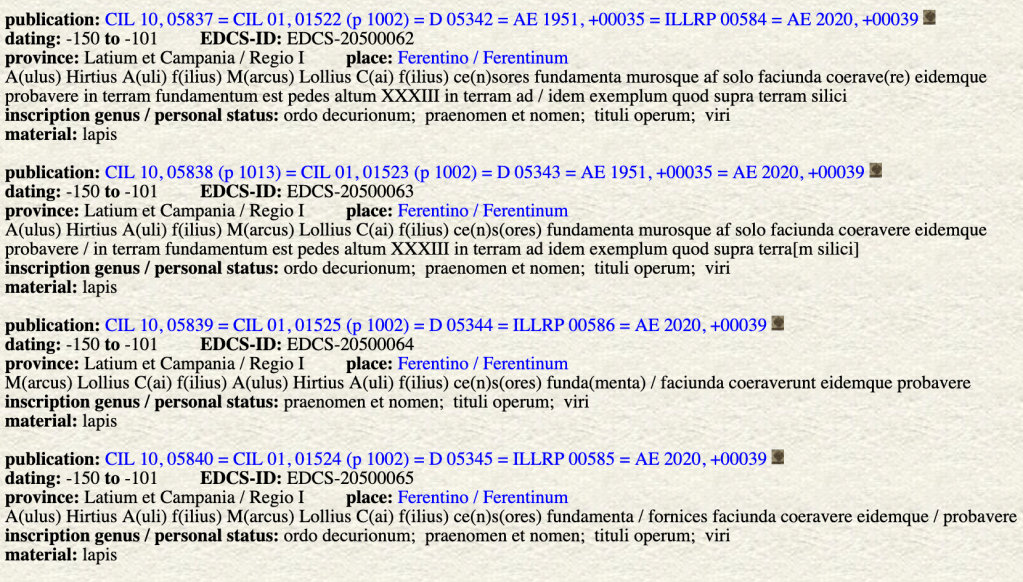

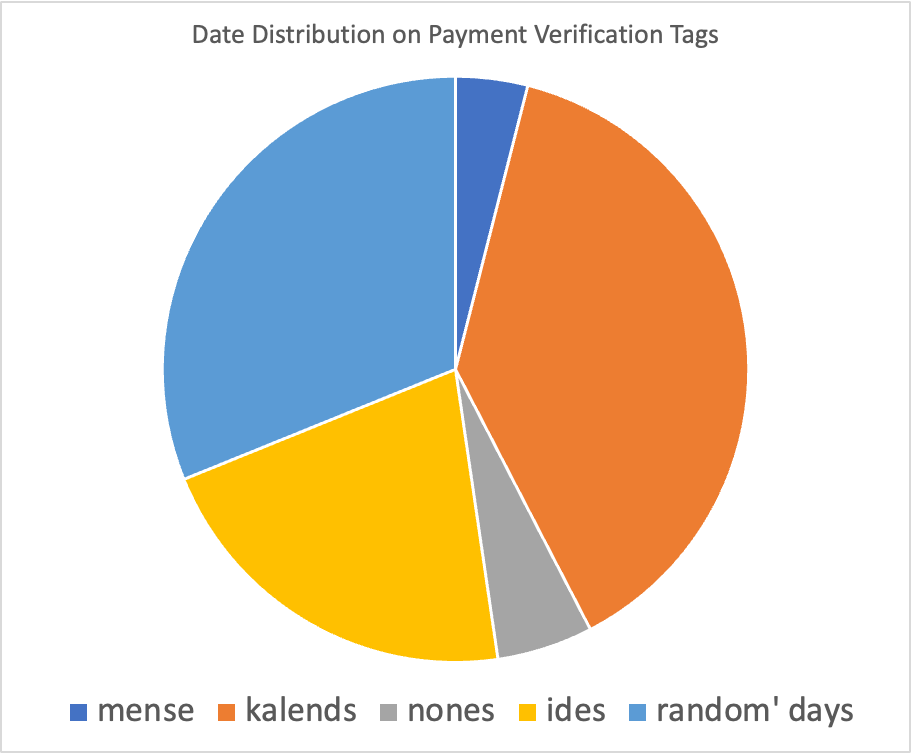

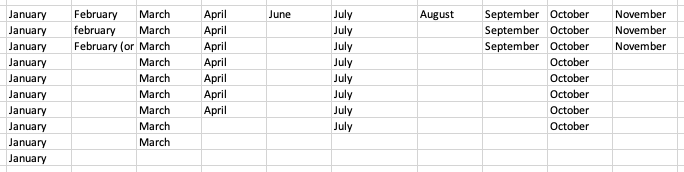

I decided to dump the data and clean it up in a proper spreadsheet. I have 151 where the date is present and legible.

While it is possible for a tag to represent almost any day in the year it is far more likely that either a fixed point of the kalends, nones, or ides will be mentioned. And by far the most common is for the payment to be made on the first of the month, and then the ides (13th or 15th of the month, an ostensible mid point).

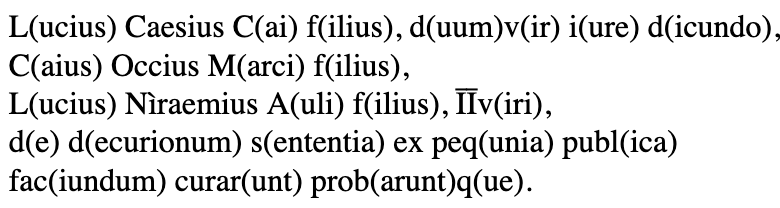

If we look a the break down by month of surviving specimens with “kalends” as the inspection date we see January as an outlier, followed closely by April and then July.

I think we’re seeing peaks on the quarters. I’d be more confident if there was a peak at October but I’d suggest this is more an accident of survival. I also suggest January may have been the preferred date for annual payments.

Ides payments seem to be fairly evenly distributed allowing for the accidents of survival with possibly a summer ‘bump’

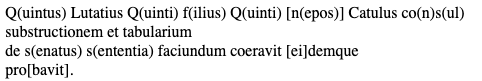

Stranger to me and perhaps a warning not to look too hard for patterns are all the other dates (including nones with the ‘randoms’):

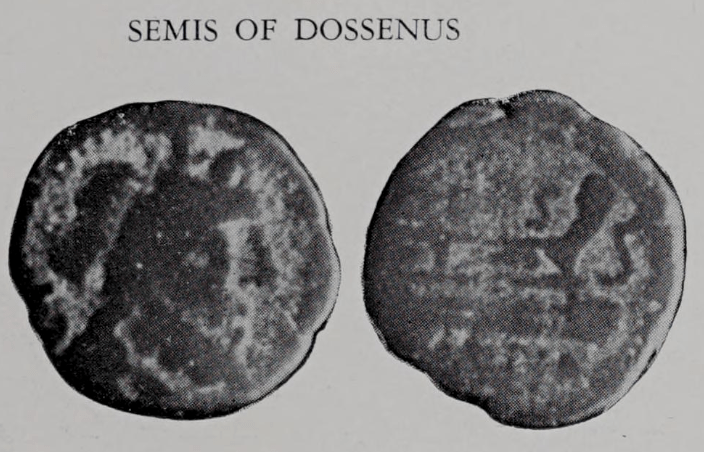

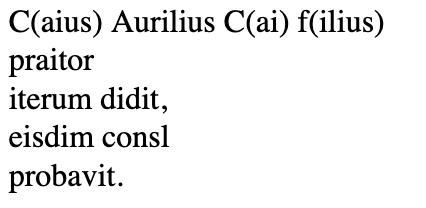

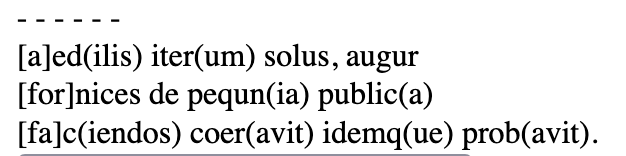

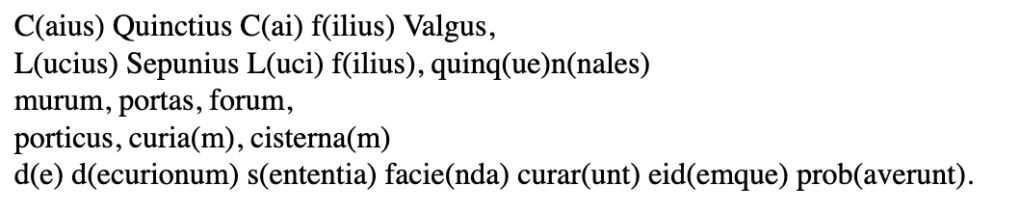

Some suggest that we might have representations of this type of tag on the RR coin series

If these are illustrations of such tags used to validate payments is the bench associated with some sort of financial office? maybe a banker? Is the Olla the type of vessel used to transport or contain these payments?

I’m agnostic about the iconography for now…

More thoughts and observations from the next day:

In the 172 cases where we can read the name of the person inspecting, enslaved or otherwise, not a single inspector name repeats. Even when the name is the same the gens of the enslaved is different.

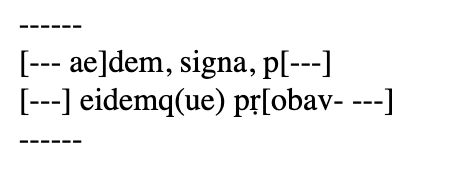

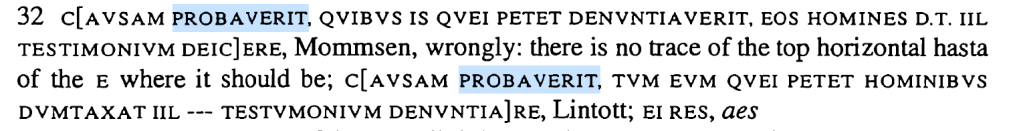

The only possible exception is as follows but I believe it to be a doublet:

When one considers the gens and other names in the genitive, the enslaver(s) of the inspectors or rarely possibly an employer, the thing that really sticks out is the great diversity. There is more repetition but not much more. 107(!) names appear only once in the genitive, typically in the masculine singular, typically the gens, but sometimes the cognomen, and sometimes with a praenomen abbreviation as well.

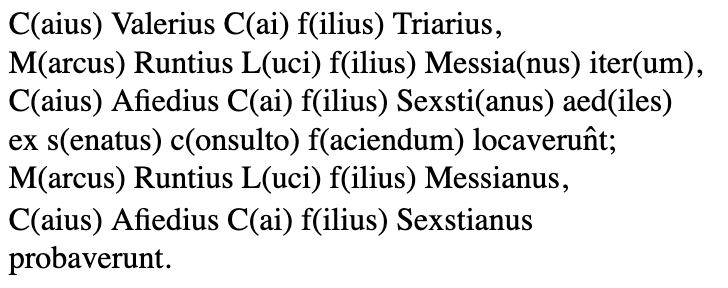

Gens appearing twice

Antoni, Caecili, Canini, Corneli, Fabi, Iuni, Licini, Novi, Valeri, Volcaci

Gens appearing more than twice

Fulvi (5 times); Hostili (3 times); Iuli (5 times), Petilli (4 times), Pomponi (3 times)

The only family names to appear in the plural are Bibulorum and Curtiorum. Here we may assume that the enslaved individual was owned by more than one family member.

We also have likely female enslavers attested: Attiae, Rupiliae, Tragoniae (only time this name occurs!)

Then there are names that seem to reflect corporate bodies:

soc(iorum) fer(rariarum)

sociorum (twice)

This great variety of names makes me lean away from associating the names on these tessera with ‘banking families’ an idea promoted by Wiseman, and thus a meaningful connection with moneyers. Rather I think it is more likely these families may be involved with a wide range of business transactions, but specifically transactions that are likely to be re occuring on an annual, quarterly, or monthly basis. Rent or interest on loans both come to mind. I’m sure their are other possibilities.

Even when names appear multiple times where dates are attested there is little to no suggestion that one individual or one generation of a family is likely with the exception of the Petilli.

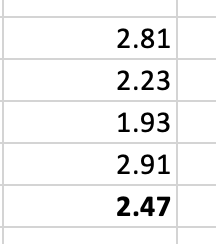

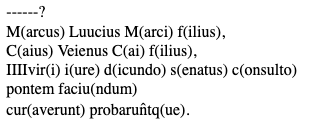

Fulvi dates: -17, -48, (no year), -60, (no year)

Hostili dates: 5, 32, -71

Iuli dates: -32, -25, 39, 83

Petilli dates: -56, -54, -46, 11

Pomponi dates: 11, (no date), (no date)

This analysis helped me identify another likely duplicate: