On themes discussed in this post, see now instead my 2021 Article.

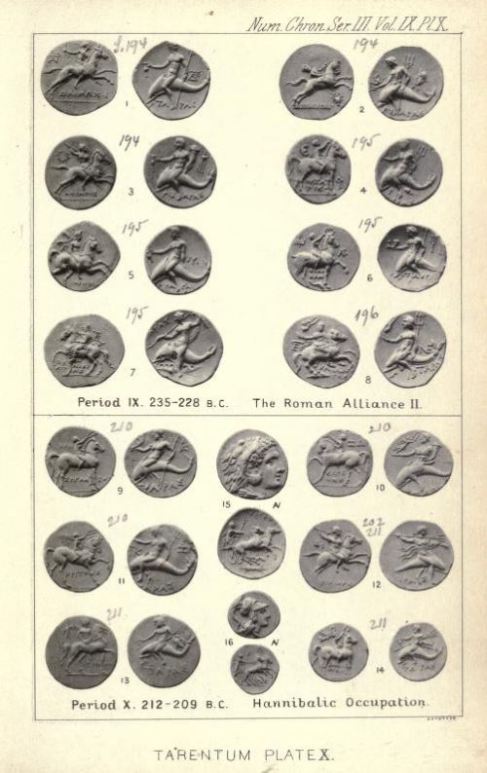

I was re-reading Tusa and Royal’s ‘landscape of the naval battle at the Egadi Islands (241BC)’ JRA 2012 and it struck me how right Eric Kondratieff was to draw a parallel between the iconography of this currency bar and rostra:

He made the argument for two rostra instead of two tridents on the basis of the Athlit Ram, a much more distant iconographic parallel, but that was before the Egadi Rams all came to light! All of the Egadi Rams found thus far have a similar design on their driving center (see Tusa and Royal link above for the anatomy of the rams), but 1 provides the best visual parallel. Given Egadi 1 has no specific provenience, it is harder to contextualize. Tusa and Royal cautiously say:

“The clear differences in iconography, inscriptions and overall shape, combined with its unknown provenience, make an association of the Egadi 1 ram with the events of the First Punic War somewhat problematic.” (p. 45 n. 92)

And earlier they noted:

“Egadi 1 has the shortest driving center of the Egadi rams, being nearly identical in length to Egadi 5, yet has the longest tailpiece and the highest mid-length height and width. The reduction from the head to constricted waist is slightly greater than from the inlet. Given the ram’s significant increase in height from its constricted waist, it possesses the third tallest and second widest head. Its large head combined with a short driving center gives this ram a stubbier design than the others.” (p. 14)

Could it be earlier? Could it be later? I’d speculate as to the former, but this is only a kneejerk instinct regarding the a likely general design trend from compact and short to long and thin. Such speculation is likely unwarranted. I could even argue against it via the ‘stubby’ appearance of the rostrum depicted on The Tomb of Cartilius Poplicola which dates to the 1st century BC (images are already up on my early post on prow stems).

William Murray, Age of Titans (2012), p. 52 gives a great illustration of a three-bladed waterline rams, just more confirmation of the rostra as the correct identification of the coin type.

Miscellaneous Post Scripts.

Another pre Egadi post Athlit publication that will be of interest to anyone interested in rams and rostra: http://luna.cas.usf.edu/~murray/actian-ram/WM-Murray-Recovering-Rams.pdf

Also on Duillus and innovations and the coinage, see Morello’s summary of his Italian publication with useful diagrams by Andrew McCabe: http://andrewmccabe.ancients.info/Corvus.html

Update 3 April 2014.

See now also my post about the rostrum on the coins of Ariminum.

HN Italy 933

HN Italy 933