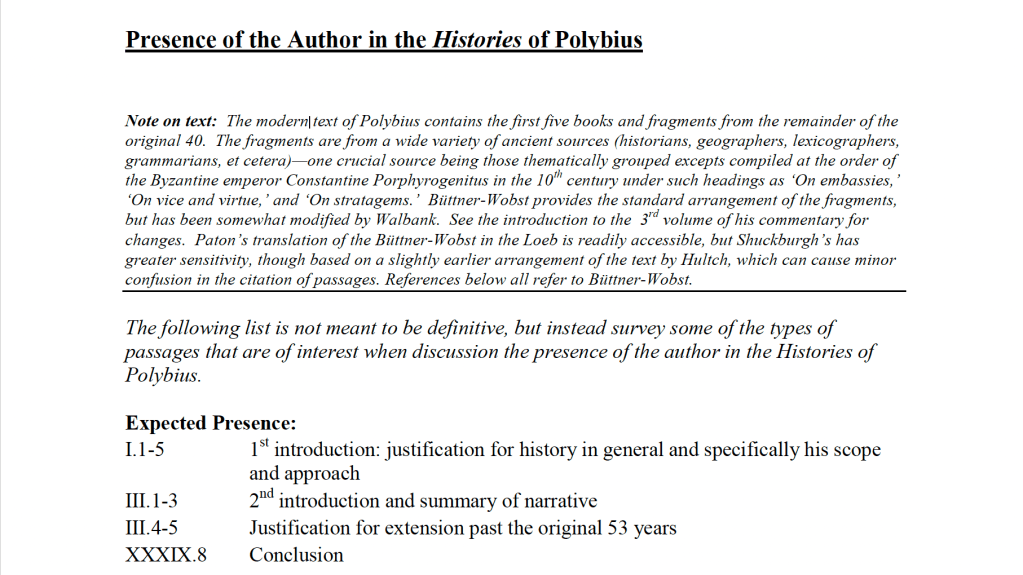

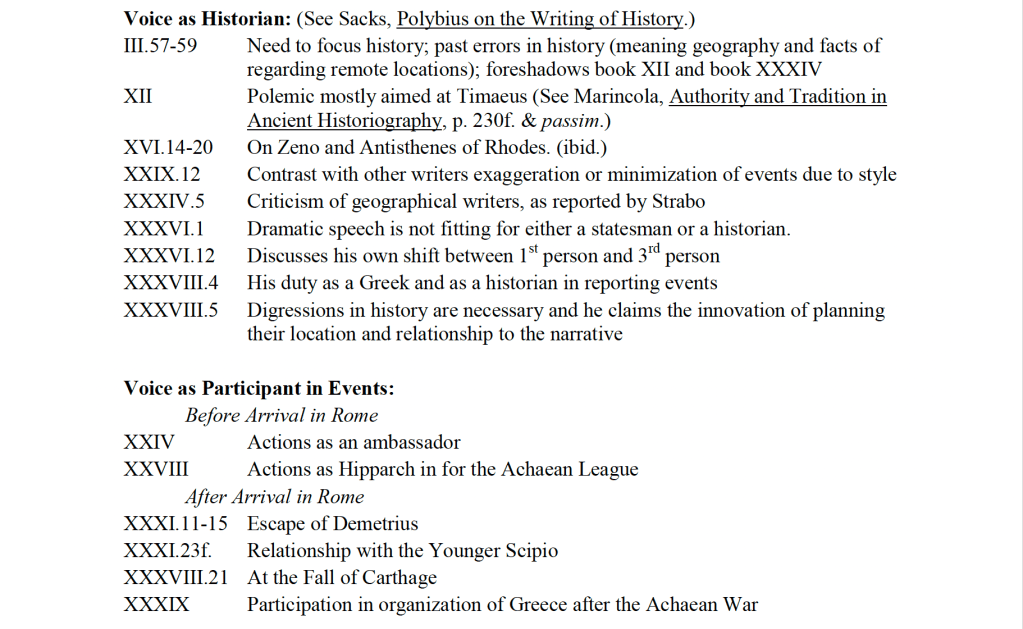

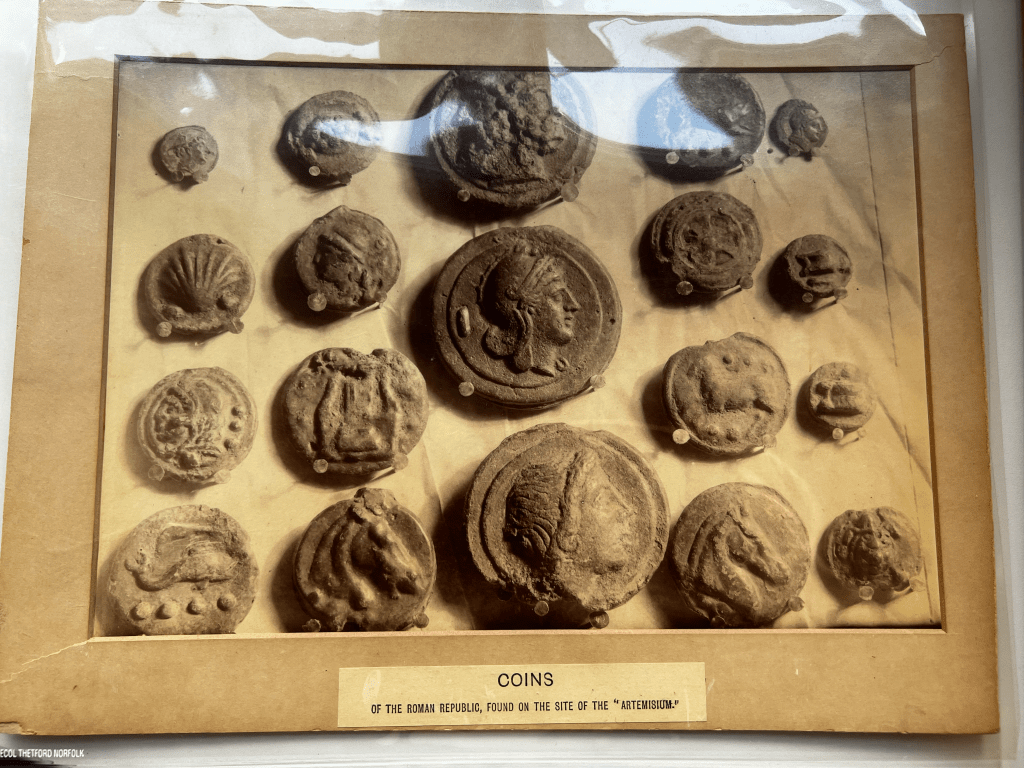

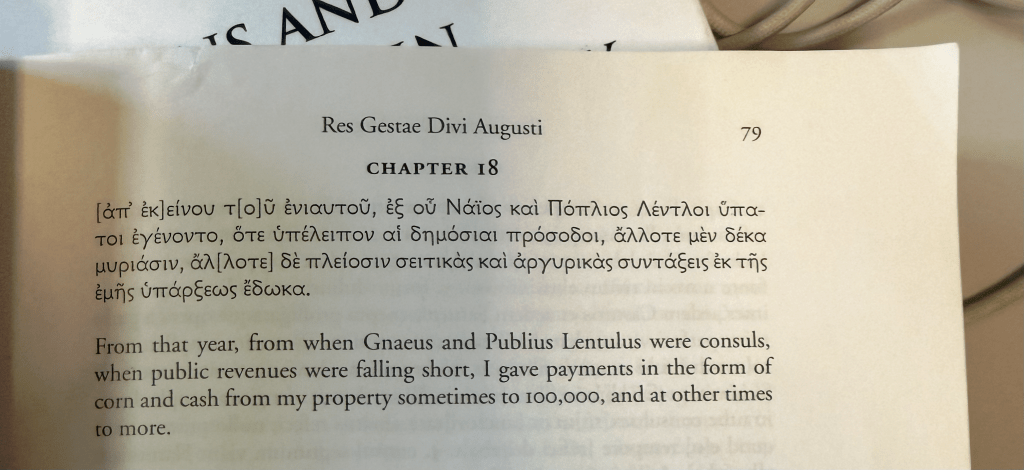

Inde ab eo anno, quo Cn. et P. Lentuli consules fuerunt, cum deficerent vectigalia, tum centum millibus hominum tum pluribus multo frumentarias et nummariás tesseras ex aere et patrimonio meo dedi.

Res Gestae 18

Beginning from the consulship of Gnaeus and Publius Lentulus, when there was a shortfall in revenues, I furnished TESSERAE for grain and coin from my own money and patrimony, sometimes to 100,000 people, sometimes to many more.

Res Gestae 18

I’m on a train and cannot check Clare Rowan’s book, but I very much want to think more of this passage. Why give out tokens in lieu of coins?! Why not just give out coins?!

Update from the library. Guess what? This is a case of a disputed reconstruction of a fragmentary text. Nothing in Rowan because most modern editions of the text use a different restoration. After my puzzlement at not finding it in her book I turned to her colleague Alison Cooley on the Res Gestae. Nothing in her commentary but a clear indication of where the Latin text does not survive and her prefered reconstruction.

…frume[ntarios et n]umma[rio]s t[ributus ex horr]eo et patr[i]monio…

The lacuna in bold another restoration is what got me all needlessly excited. So I needed anapparatus criticus to catch up on how we ended up with the now widely preferred reconstruction. My suspicion was that this was because of the Greek translation that also survives, but I wanted to see how I’d been misled by the internet.

Augustus, Jean Gagé, and Wilhelm Weber. Res gestae divi Avgvsti : ex monvmentis Ancyrano et antiocheno latinis : Ancyrano et Apolloniensi graecis : texte établi et commenté (avec un appendice et 4 planches hors-texte). [2d ed.]. Paris: Société d’éditions : Les Belles lettres, 1950. Print.

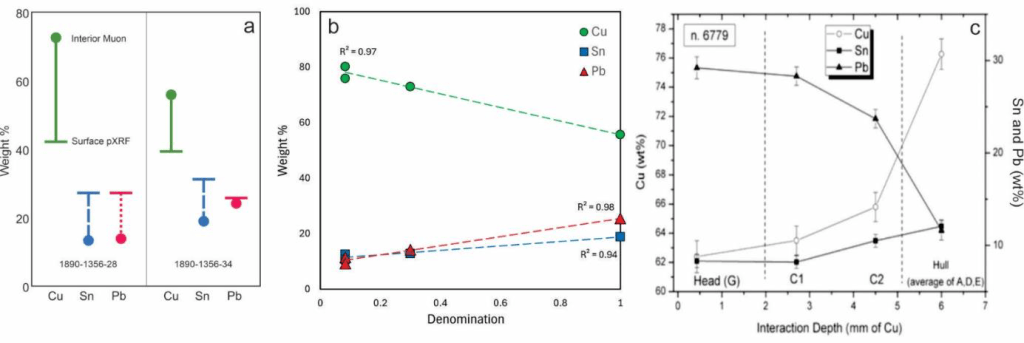

Gagé prefers the same reading of Cooley (as has basically everyone for a long while), but he reports (p. 106) a number of previously suggested alternatives

Mommsen 1883 wanted ‘tributus ex agro’

Wölfflin 1986 wanted ‘teseris diuisis ex patr…’

Craget 1919 and Schmidt 1887 both preferred the reading which I originally posted above.

Markowski 1932-1933 suggest ‘tabulas e fisco…’

As you can see the Greek is far better preserved and makes clear no tokens need be involved

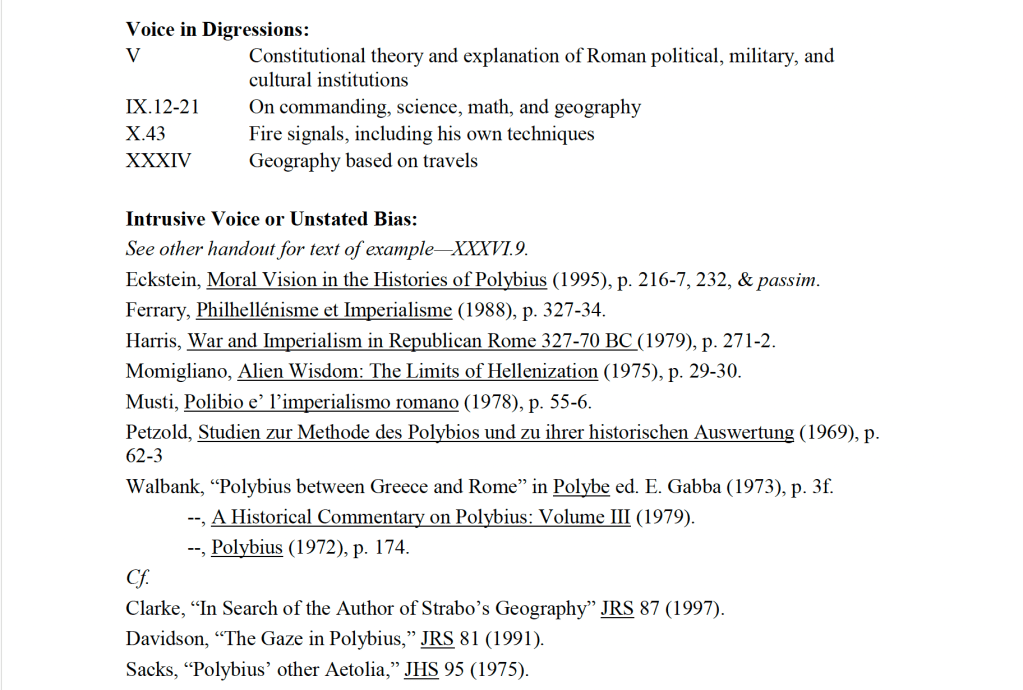

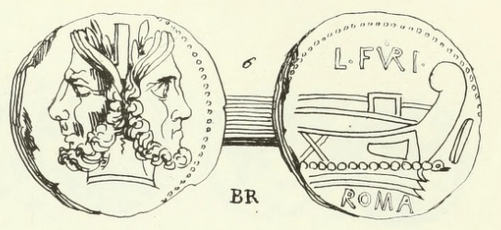

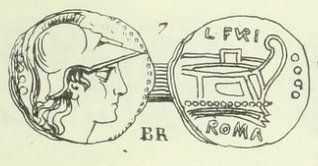

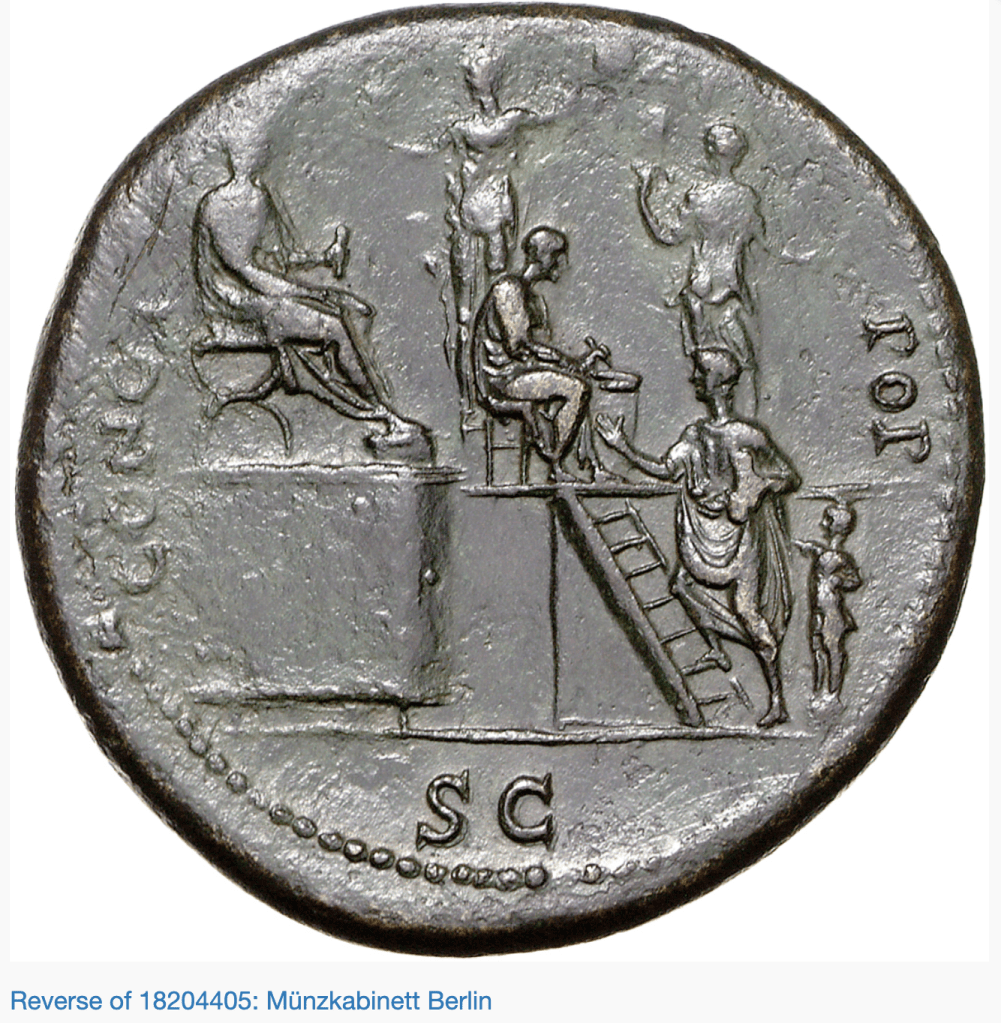

We get our first scenes of Liberalitas and the money shovel starting under Nero.

The thing to read is

Beckmann, Martin. “The Function of the Attribute of Liberalitas and Its Use in the Congiarium.” American Journal of Numismatics (1989-) 27 (2015): 189–98. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90017068

.

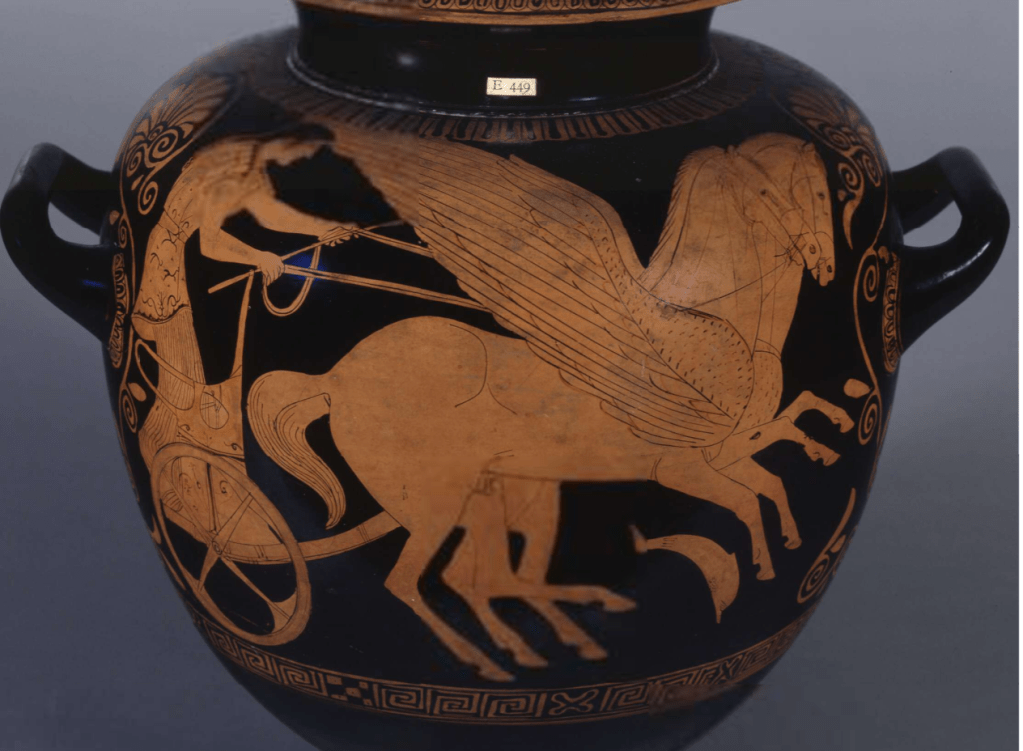

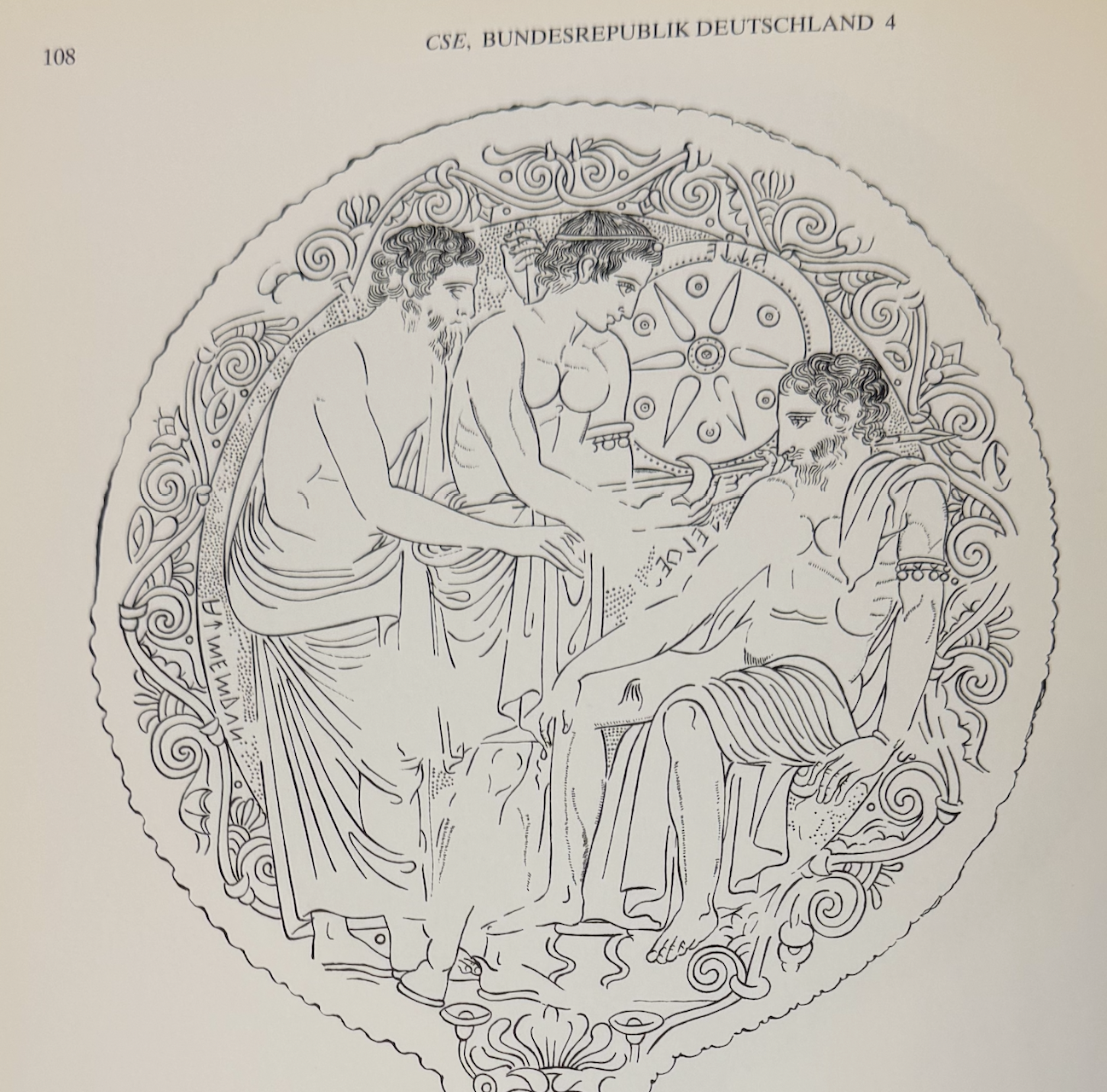

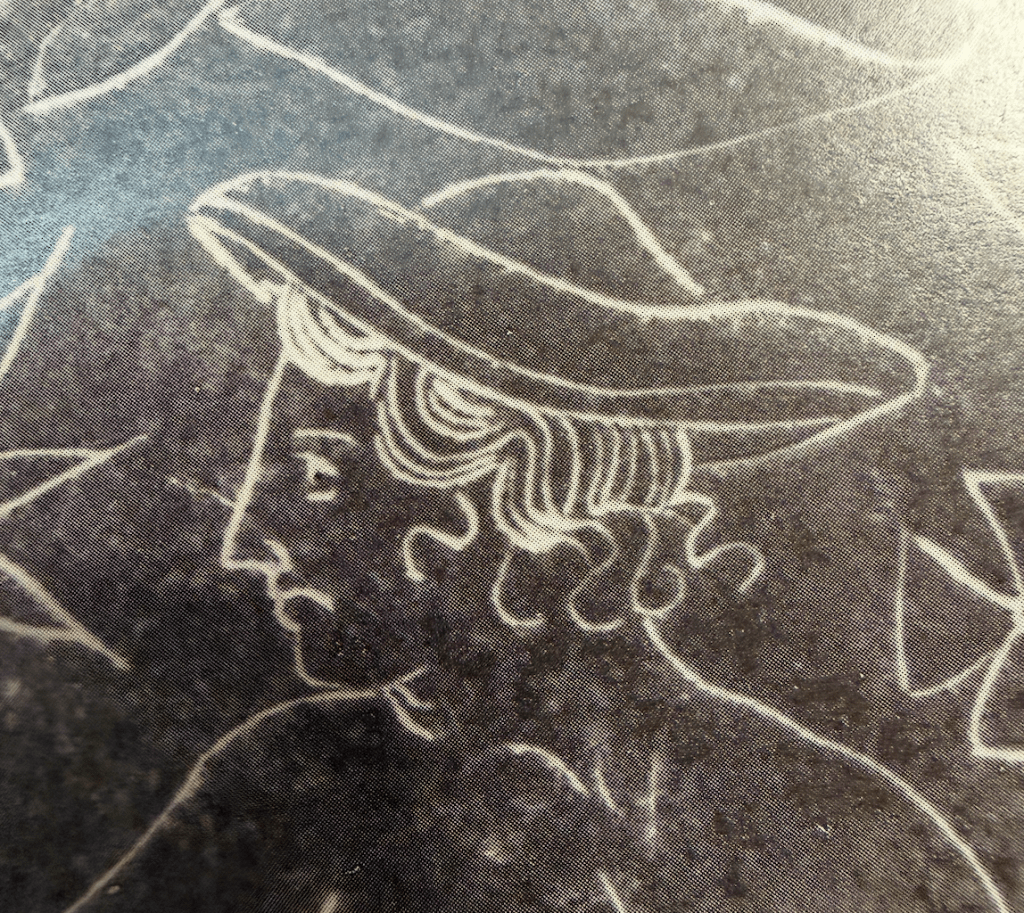

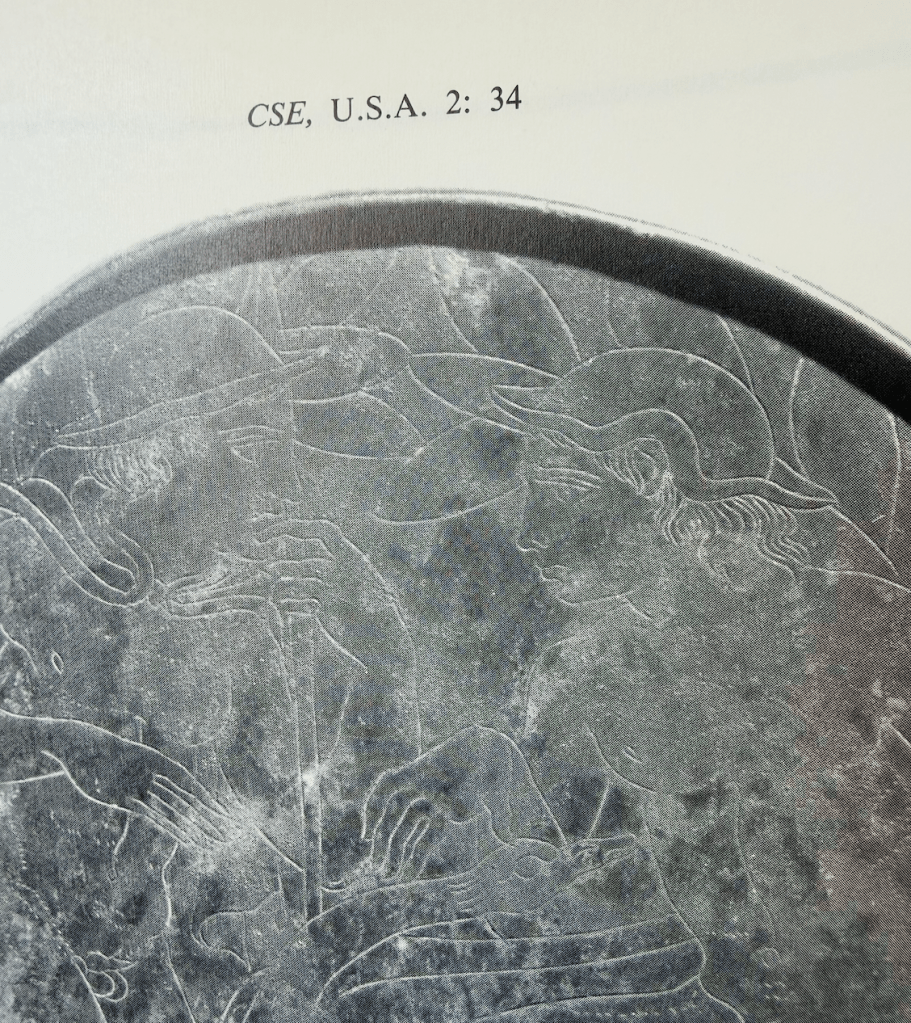

The iconography remains incredibly consistent through out the empire. Liberalitas holds her money shovel high. (too often wrongly called a tessera in catalogues). The recipient(s) ascend the steps in a toga, often using the toga to collect their allotment of coin. The emperor is separate but present.

So when was the money shovel invented?! And what made it more convenient for Augustus to give out tesserae and then have a secondary collection point. The logistics of largess need work.

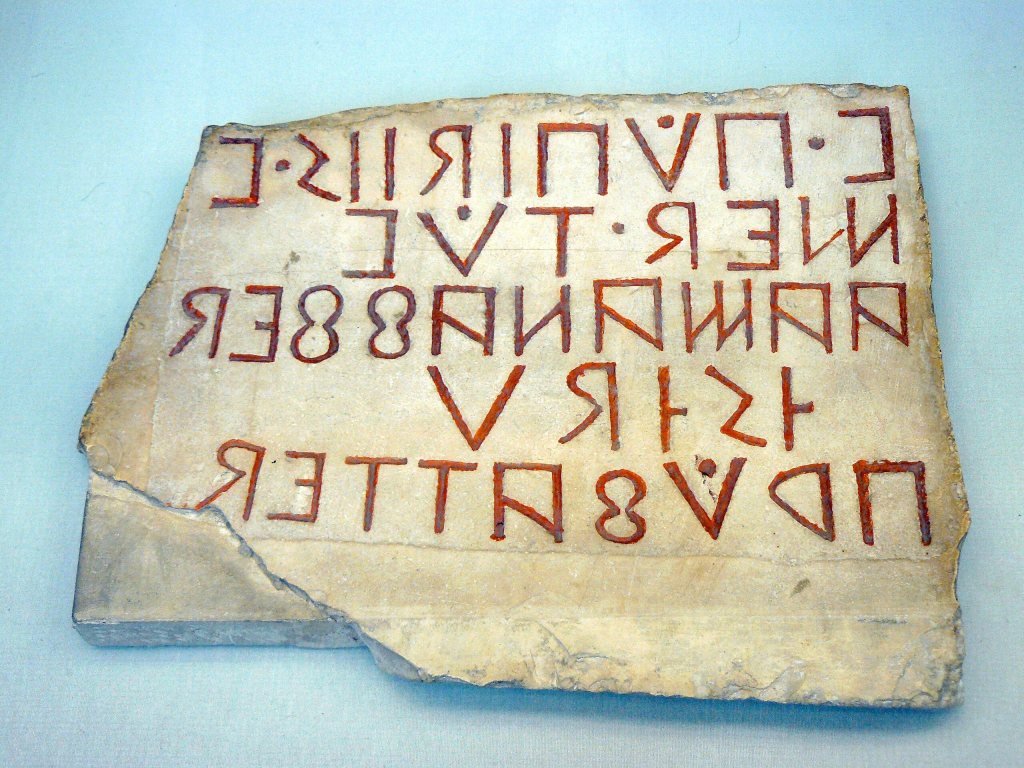

Also if there were a 100,000 plus such tesserae for any given distribution, surely some should survive?!

I was reading the Res Gestae for a totally different reason but got distracted by the above passage. ho. hum.