This as of L. Rubrius Dossenus (c. 87 BC) has, instead of the standard Janus, a janiform head combining Hercules and Mercury. Alföldi connects this image, not to the palestra hermerakles imagery representing sound mind and sound body, but instead to a rather unusual vase image. (See yesterday’s post for bibliographical citation).

Update 7/1/2020: Crawford judged Alföldi’s interpretation implausible in his 1984 Edinburgh catalogue. See McCabe for summary.

The thing to notice is that the body of the figure is covered in eyes. This is the standard means of depicting Argos Panoptes, the giant covered in uncountable eyes set to guard Io and killed by Hermes. He is the mythological representation of the ever vigilant watcher.

A more recent monograph on the Polygnotos painter questions whether the standard identification of the figures (i.e. Hermes slaying Argos to free Io) on this most unusual vase are correct given how much it diverges from the standard representation:

Maybe this is not Hermes or Io, I grant their iconography isn’t typical, but Panoptes is surely intended on the vase given how his body is covered with eyes. Perhaps we’re not seeing the right Argos Panoptes narrative here; the scholia on Euripides knew of other adventures in which he was a more positive protector, even if the vast majority of literary accounts are on Io. There is even an early suggestion that Argos only had 4 eyes like a Janiform god:

Hesiod or Cercops of Miletus, Aegimius Frag 5 :

“And [Hera] set a watcher upon her [Io], great and strong Argos, who with four eyes looks every way. And the goddess stirred in him unwearying strength: sleep never fell upon his eyes; but he kept sure watch always.”

Is Alföldi’s suggestion plausible? Maybe. The vase certainly isn’t the standard representation but it is of Italic origin and we may be missing other key evidence. That said, the vast majority of viewer would have been more familiar with the palestra imagery. Cf. Cicero’s reference to wanting such a statue (ad Att. 1.10.3):

We imagine this would be something like this:

Or like this one in the Boston MFA Collection:

That it is the two individual deities combined in one image which is intended on the coin seems to me to be more likely, given that the inclusion of the attributes of both in the design. This is not that visible on the specimen, but is noted by Crawford and can be seen on this coin of Andrew McCabe:

See how a club and caduceus jut out on either side below the chin and above the shoulder.

Why did Alföldi find the Argus explanation so attractive? It allowed him to connect the coin to contemporary politics especially the vigilance of the Marians in anticipation of Sulla’s return. (He dates the series to 86 BC.)

All that said it is also possible the Cicero/Palestra theory is a red herring. Cicero might not have meant double herms but instead statues like this:

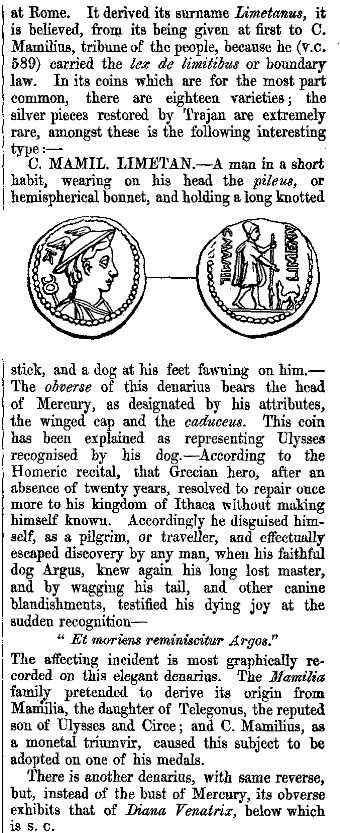

A little later aside (11/11/13): In that way that so often happens, I came across an odd coin with slightly similar imagery today. Perhaps, I noticed it because I’d been looking at these janiform/bifrons heads yesterday. I’m putting it up just so I have a note of it, should it ever prove relevant:

Another potential piece of comparative evidence (found 23/12/13):

Listed on Flickr as:

Janus-herm with addorsed head of Pan [or Zeus Ammon?] and Hercules, Marble, Roman, 1st c. CE; George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, 51.2002.10; Springfield, Massachusetts, Gift from the Estate of Dr. Melvin N. Blake and Dr. Frank Purnell

Update 30/1/2014: Discussing Janiform head could also lead to an investigation of this sort of object:

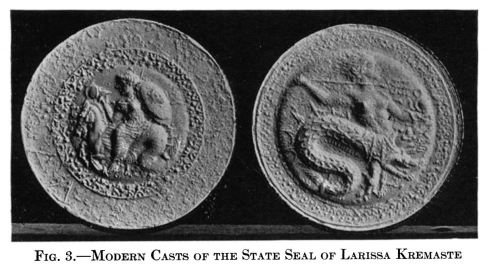

3/22/14 update: Compare the coinage of Volaterrae with the image of Argos on the vase painting above. Note in particular the hat and the club:

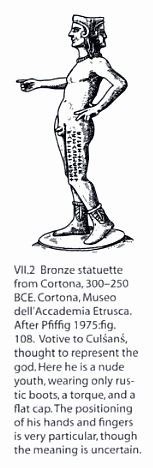

Also of interest is the iconography of the Etruscan god, ‘Culsans’:

Note that the official museum catalogue website describes the headdress on this statue as a wild animal skin.