It’s official! My team has been awarded SIX DAYS of beam time! [we run experiments 24-7 during that time, taking over night shifts in rotation] Below you’ll find the whole grant narrative. All going well we should be able to make comparisons between and within all common Roman aes grave series, and establish original ‘recipes’ for the lead heavy admixture. I’m already dreaming about how to apply this data to other votive offerings and experimental archaeology to explore casting technologies!

Stable Currency? Variable Cu:Pb:Sn Alloys and the Value of Rome’s Cast Coinages

L.M. Yarrow (ICS, SAS, London), W. Powell (CUNY), A. D. Hillier (STFC), S. Biswas (STFC), A. Inscker (Nottingham)

I. Background and Context

This cultural heritage proposal seeks to determine whether the composition of Rome’s earliest cast coinage, called aes grave (‘heavy bronze’) was an intentional and stable admixture of metals, particularly whether there was a stable ‘recipe’ within series and between series. The Romans seem to have adopted the tradition of using roughly shaped copper alloy ingots as money from northern and central Italic cultures and married this tradition to the design habits of the silver coins introduced by Greeks of southern Italy. This resulted in a perplexingly heavy cast coinage with numerous fixed denominations of an uncertain ‘bronze’ alloy or alloys. There is no definitive explanation for why they would be made so large or in so many denominations. Until recently, the prevailing scholarly view was that the heft of the objects (>300g for the largest denomination) corresponded to intrinsic value, but recent work on their metrology, pXRF surface analyses, and the results from preliminary MuX experiments (RB 2410477), make this view untenable. (1,2,3) This calls into question the origins of Roman money and by extension how we conceptualize the evolution of economic systems writ large. In essence, we’re asking if these objects were more akin to poker chips than a raw commodity.

II. Proposed Experiment

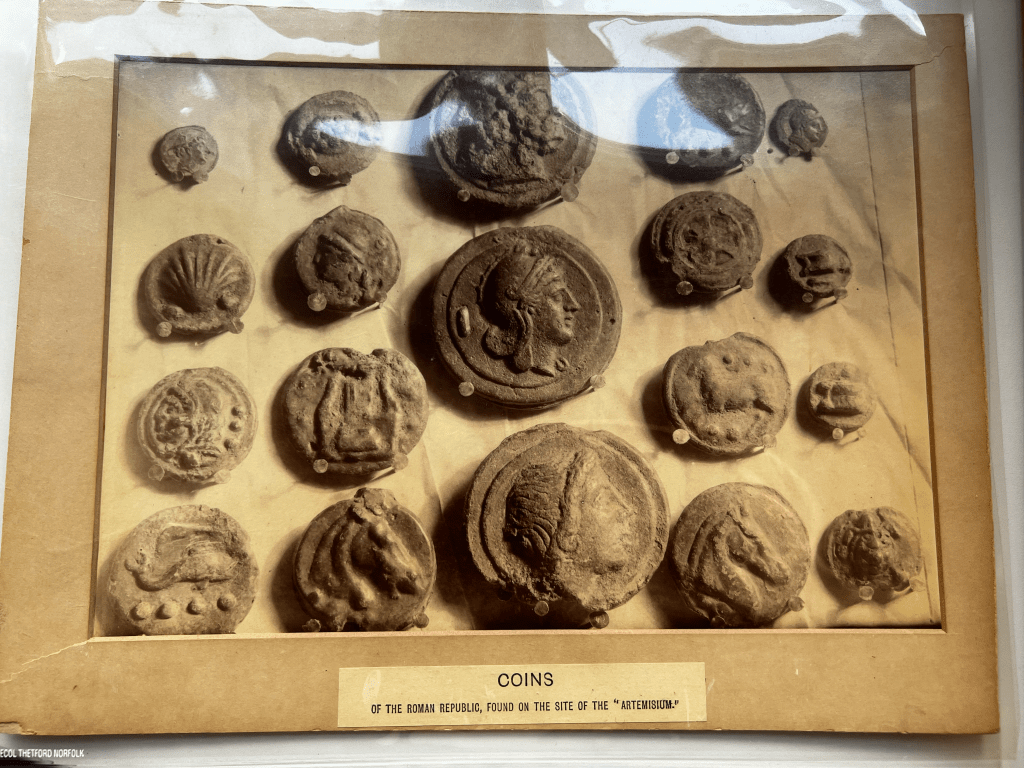

We seek to characterize the composition of the Nemi assemblage in Nottingham. Our fundamental research question is whether or not these coins were created using an intentional, controlled ‘recipe’, and if so, if it remained consistent across denominations and across series. This data allows us to test hypotheses regarding chronological sequencing and place of production. The experiment focuses on smaller denominations, allowing for multiple specimens from the same series to be compared one to another (series consistency), as well as direct denomination to denomination comparison between series (temporal/regional consistency). Smaller denominations (1/12th; 1/6th), with smaller mass and volume, are more likely to have quenched upon casting, thereby avoiding complications associated with compositional heterogeneities arising from the segregation of immiscible melts during cooling. At least two, and where possible three, examples from each series will be analyzed to test for compositional consistency. Coins from seven stylistically, and potentially temporally distinct, series will be analyzed to investigate compositional consistency interregionally and across time. Analyses will be focused at a depth of 2mm. This optimal depth avoids compositional transformations associated with weathering, but is shallow enough to remain in the compositionally homogenous quenched region, as determined from prior studies of leaded bronze at the ISIS facility(4). The material from Lord Saville’s 1880s excavations at the sanctuary of Diana at Nemi (Fig. 1) is curated by Nottingham City Museums & Galleries. Securely provenanced collections of aes grave including nearly all known series and denominations are exceptionally rare. The objects have all been previously tested using pXRF, and we can be confident in both authenticity and common conditions of ancient deposition and post-excavation storage, ensuring comparison between objects and series are valid and reasonable. Any destructive technique, such as drilling, is ruled out with respect to the cultural heritage importance of these objects. Even if seemingly similar objects are available in other collections, and even on the antiquities market we have no means (yet!) to ascertain if such objects are genuine without a clear chain of custody from the point of excavation. Forgery of such objects has been rampant since the early modern period. It would be deeply unethical to drill the only assemblage with archaeological provenance in the whole of the UK and one of only a handful globally; all the others are subject to strict protections by Italian law. We expect that the original ‘recipe’ should be consistent within series, or at least within the same denomination within a series. It may also be consistent across series, or show evolution over time. Any demonstrable difference will be historically significant in determining the economic function of the objects, and potentially, for confirming the relative chronology and relationships between the series. The sequence of creation is disputed, as is the length of time over which these objects were created and used. We theorize that the earliest were made just before the 1st Punic War (c.265BCE) and production continued through the beginnings of the 2nd Punic War (c.215 BCE). These analyses will help us better understand the socio-economic role of all bronze objects from this period, from their military applications to their status as religious offerings, including but not limited to those headline grabbing discoveries at San Casciano dei Bagni (Tuscany). At a meeting of the American Institute of Archaeology in January 2025, researchers from this site presented exceptional new discoveries from the 2024 excavations revealing that bronze votive statues bore inscriptions testifying to their weights. This religious context is not unlike what we know of the Nemi sanctuary. The heaviness of the object may have religious as well as economic significance.

Results will be calibrated through comparison with analyses of an international Pb-bronze standard (MBH-32XLB12). Based on the ISIS experiment RB2410477, we believe one analysis for each 1/12th piece is sufficient. As we lack comparanda for the larger 1/6th pieces, one reading from each side of each object ensures that we can determine if cross-denominational comparisons are valid. The assemblage contains only a single coin from series RRC25. This coin is a 1/3rd piece. An analysis at a depth of 2mm will be taken for comparison with the other series. Additional analyses will be taken at depths of 4mm, 6mm, and 8mm, to investigate potential internal inhomogeneities. This data will inform future studies in developing analytical methods for larger aes grave denominations and related artifacts.

III. Summary of Previous Beamtime or Characterization

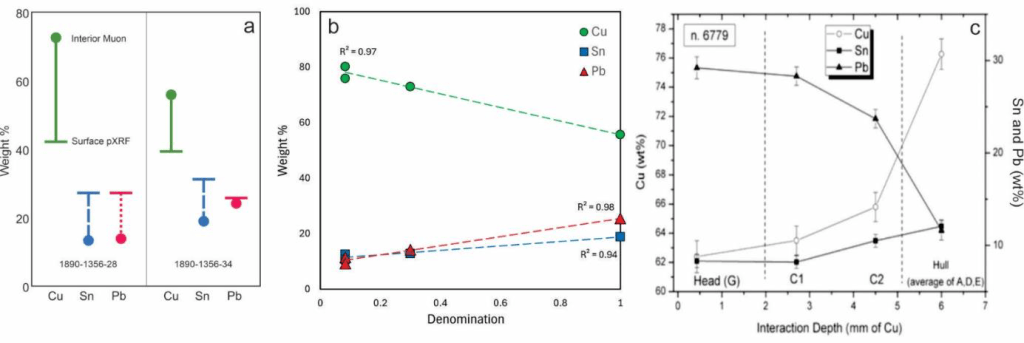

Weathering of leaded-bronze results in a loss of Cu and a corresponding increase in concentrations of Sn and Pb in the patina. Our initial results (RB 2410477) prove that even artifacts that lack evidence of patina development (absence of O, C, S, and Cl based on pXRF analysis), exhibit large and non-systematic variance between analyses if the surface by pXRF compared to interior analyses using muonic x-rays (Fig. 2a). Thus, only internal analyses of bronze artifacts are meaningful. Our initial, exploratory experiments at ISIS suggest that the composition of aes grave vary linearly with their fractional denominations (1, 1/3rd, 1/12th) (Fig. 2b). A prior muonic x-ray study on leaded-bronze found that the compostion remains consistent within the first two millimeters, but at greater depths there is a non-linear shift in composition due to the development of immiscible melts during the cooling process (Fig. 2c) (ref). Accordingly, we conclude that these linear compositional trends at the 2mm depth across denominations is more likely to be the result of intentional ‘recipe’ modifications, rather than complications due to phase separation. RB 2410477 was critical for developing appropriate testing methods and furthered our understanding of how to use MuX to collect data from heavily leaded samples. This follow-up allows for a corresponding leap in our knowledge of this type of artifacts.

IV. Justification of Beamtime Request

Analysis of sizable Pb-Sn-bronze artifacts such as these aes grave requires a non-destructive, deep-penetrating method that can document variation in composition with depth, and position. Muon X-ray emission spectrometry, as available at ISIS on the MuX instrument, is ideal for this purpose. Invasive techniques are ruled out by ethical concerns.. Neither surface analyses, nor neutron activation can provide reliable documentary evidence of the original “recipe(s?)” again because of inconsistent internal structure of the leaded bronze admixture and the high levels of patinatation and/or environmental incrustation from the conditions of deposit. 144 hours of beam time (6 days on the MuX spectrometer) would allow characterizing an international Pb-bronze standard (MBH-32XLB12) (5 analyses at surface, 2mm, 4mm, 6mm, and 8 mm; c. 20 hours), as well as 16 cultural heritage objects (32 analyses total). These objects include (a) 7 1/12th pieces, 1 analysis each aiming to reach a depth of 2mm, c. 28 hours, (b) 6 1/6th pieces, two analyses each at 2mm, one on each side of the object, c. 40 hours, and (c) 3 1/3rd pieces, four analyses at 2mm, 4mm, 6mm, and 8 mm, c. 16 hours (d) one additional surface reading on 1 1/3rd piece. The two surface readings allow us to demonstrate pXRF data and MuX data can be accurately compared for Pb-bronze objects. Testing the smallest available denomination of each of 7 series of cast bronzes and characterize any difference within and between the series. These results will be integrated with the results of RB2410477 for publication and should allow us to confirm either an intentional recipe for the alloy across denomination and series, or instead address the historic implications of either intentional recipe adjustments or a disregard for precise metal content.

1 Baldassarri, et al. (2006). Analisi LIBS di esemplari di AES Rude… Cong. Naz. di Archeometria IV, 561-573.

2 Ingo et al. (2005). Microchemical investigation of archaeological copper… . Microchimica Acta 144, 87-95.

3 Yarrow. (2023). Strangeness of Rome’s Early Heavy Bronze Coinage. In Making the Middle Republic, 103-31.

4 Cataldo et al. (2022). A novel non-destructive technique for cultural heritage … negative muons. App. Sci., 12, 4237

One thought on “Aes Grave MuX Grant Approved!”