I”m trying to get out ahead on some of my commitments, I have three new papers for delivery to write (all eventually needing to be published) and two PR publications to draft, revise and submit by the end of the semester. Will I do it? Maybe maybe not. Something may have to give.

Must be cited

- Konrad, Christoph F. “Some friends of Sertorius.” The American Journal of Philology 108, no. 3 (1987): 519-527. (Jstor)

Very solid straight forward prosopographical/career overview of Annius’ quaestors who struck RRC and defected to Sertorius.

- Antela-Bernárdez, Ignacio Borja. “Anio, Fanio y Tarquitio en las Guerras Sertorianas.” Latomus 76, no. 3 (2017): 575-593. Doi: 10.2143/LAT.76.3.3275127 [Jstor – extensive notes below]

This is a much more detailed treatment of an earlier article on the same topic by the same author: Antela Bernárdez, Ignacio Borja. “Los cuestores de C. Annio y el gobierno provincial en Hispania.” L’Antiquité Classique 82 (2013): 263-265. Doi: 10.3406/antiq.2013.3838

Possibly relevant

- Woytek, B. “Ein frühneuzeitlicher Aureus des Nerva mit PAX AVGVSTI und ein überprägter Victoriat im Namen des Sertorius.” NZ 125 (2019): 73-87. [ILL requested – excited to see if this connects with my current interest in fantasy pieces.]

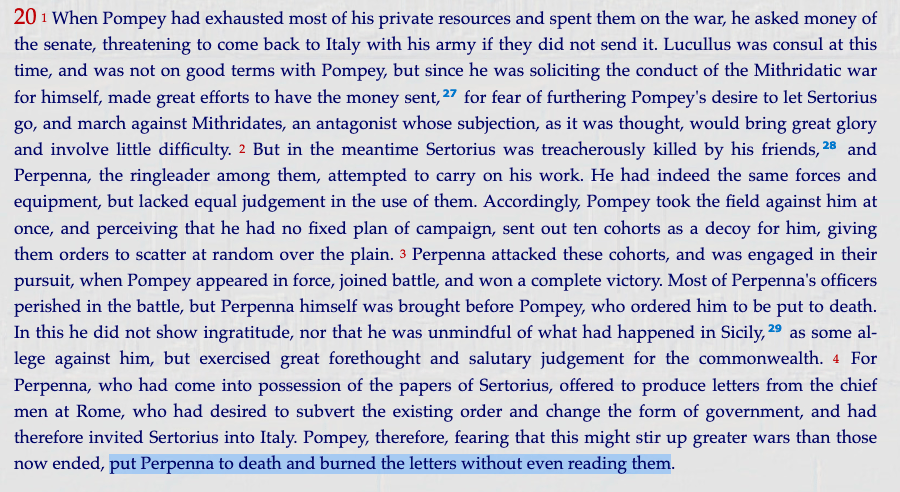

- Konrad, Christoph F, and Plutarch. Plutarch’s Sertorius : A Historical Commentary. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994. [on my shelf]

- Gaggero, G. “Aspetti monetari della rivolta sertoriana in Spagna.” Rivista Italiana di Numismatica 78 (1976): 55-75. [ILL requested]

- García Cardiel, Jorge. “La cierva de Sertorio en su contexto (ibérico): poder, adivinación e integración en la Hispania tardorrepublicana.” Latomus 79, no. 2 (2020): 317-339. Doi: 10.2143/LAT.79.2.3288653

- Arrayás Morales, Isaías. “Conectividad mediterránea en el marco del conflicto mitridático.” Klio 98, no. 1 (2016): 158-183.

- Syme, Ronald. “« Rex Leptasta »: (Hist. II, 20).” In Approaching the Roman revolution : papers on Republican history, Edited by Syme, Ronald and Santangelo, Federico., 122-127. Oxford: Oxford University Pr., 2016.

- García González, Juan. “« Quintus Sertorius pro consule » : connotaciones de la magistratura proconsular afirmada en las « glandes inscriptae Sertorianae ».” Anas 25-26 (2012-2013): 189-206.

- Domínguez Arranz, Almudena and Aguilera Hernández, Alberto. “Del « oppidum » de Sertorio al « municipium » de Augusto : la historia reflejada en el espejo de las monedas.” Bolskan 25 (2014): 91-109.

- Manchón Zorrilla, Alejandro. “« Pietas erga patriam » : la propaganda política de Quinto Sertorio y su trascendencia en las fuentes literarias clásicas.” Bolskan 25 (2014): 153-172.

- Mederos Martín, Alfredo. “El periplo insular y continental norteafricano de Sertorio (81-80 a.C.).” In « Libyae lustrare extrema »: realidad y literatura en la visión grecorromana de África : homenaje al prof. Jehan Desanges, Edited by Candau Morón, José María, González Ponce, Francisco José and Chávez Reino, Antonio Luis. Literatura; 98, 99-116. Sevilla: Ed. Universidad de Sevilla, 2008 (impr. 2009).

Not particularly relevant to my work now but worth remembering

- Bennett, William H. “The death of Sertorius and the coin.” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte H. 4 (1961): 459-472. [JStor]

This is a fascinating look at a passage of Appian and the era years on the coins of the kingdom of Bithynia to make a case for Sertorius dying in Spring of 73. It has been cited relatively widely but not as I can see widely adopted (cf. DPRR). Honestly, I just loved reading it for how it drew history and coins together without apologizing or soft pedalling the analysis of either. I don’t know or have time at this moment to comment on accuracy of conclusions. Do you know? Let me know!

- Scherr, Jonas. “Die Jünglinge von Osca.” Antike Lebenswelten: Althistorische und papyrologische Studien (2015): 282. [on Academia.edu]

Concludes that Plutarch, Sertorius 14,1–4 must be read in a primarily cultural/literary method and that it cannot be taken as evidence of Sertorius’ actual policies or practices.

Iberian Numismatics

I should probably ILL all of these I cannot access online, but my mandate is to talk about iconography and the Roman mint so I’m just leaving the refs hear for now.

- Medrano Marqués, Manuel. “El campamento de Quintus Sertorius en el valle del río Alhama (Fitero-Cintruénigo, Navarra).” Cahiers Numismatiques 159 (2004): 15-32.

- Bruni V., La moneta provinciale in Spagna durante la guerra sertoriana (82-72 a.C.) INC XV Proceedings, p. 656-660.

- Alonso, Carmen Marcos. “La moneda en tiempos de guerra: el conflicto de Sertorio.” In Moneda y exèrcits: III Curs d’Historia monetaria d’Hispania, pp. 83-106. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 1999.

- Doménech-Belda, Carolina, and Feliciana Sala-Sellés. “Two lead coins with the legend N· CALECI from Sertorian forts of the Roman civil wars in Hispania.” (2021).[link to full text]

- Salinas Romo, Miguel. “Apuntes en torno a las guerras sertorianas : evolución e impacto sobre el poblamiento y la ordenación territorial del valle del Ebro.” Espacio, Tiempo y Forma : Revista de la Facultad de Geografía e Historia. Serie 2, Historia Antigua 27 (2014): 15-53. Doi: 10.5944/etfii.27.2014; 10.5944/etfii.27.2014.14163

- López Sánchez, Fernando. “Moneda ibérica y « gens Mariana » (107-90 a.C.).” Gladius 30 (2010): 171-190.

Abstract of last: The division between horseman reverses with a palm (“domi”) and armed horseman (“militiae”) in Iberian coinage allows us to affirm that some Iberian mints correspond to military camps. Thus, the denarii of “Ikale(n)sken” should be associated with the troops sent by the city of Kese to Córdoba in support of Sertorius (97-93 BCE). The denarii of “Sekobirikes,” on the other hand, are the coins of Sekaisa’s troops in the territory of the Arevaci under T. Didius and V. Flaccus (98-92 BCE). The Catalan bronze series all correspond to the beginning of the Bellum Sociale (90 BCE). Rome fought in Hispania during the 2nd century BCE at the invitation of cities such as Segeda-Sekaisa, which were threatened by overly powerful enemies. Iberian armies fought in the Roman manner in the time of Marius. Classical Iberian coinage was minted between 107 and 90 BCE. It reflects not the Roman conquest of Hispania, but the formation of a Hispano-Roman branch of the Roman army.

- Chaves Tristán, Francisca, García Vargas, Enrique and Ferrer Albelda, Eduardo. “Sertorio: de África a Hispania.” In L’ Africa romana. Atti del XIII convegno di studio: Djerba, 10-13 dicembre 1998, Edited by Khanoussi, Mustapha, Ruggeri, Paola and Vismara, Cinzia. Collana del Dipartimento di Storia dell’Università degli Studi di Sassari. Nuova serie; 6, 1463-1486. Roma: Carocci, 2000.

“Ricostruzione dell’itinerario percorso da Sertorio, sulla base di ritrovamenti di monete africane nella zona di Cadice e grazie al contributo delle fonti letterarie (soprattutto Plutarco, Strabone e Sallustio)”

- Arévalo González, Alicia and Marcos Alonso, Carmen. “Dos reacuñaciones romano-republicanas sobre moneda hispánica.” Madrider Mitteilungen / Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Madrid 38 (1997): 67-74.

“Models of two coins from Cáceres el Viejo (Provincial Museum of Cáceres) and Torelló d’en Cintes (Museum of Fine Arts of Mahón, Menorca), which not only document the first known Roman republican overstrikes on Hispano-Iberian coins but also provide evidence for mintings before the emissions of the Pompeian party. The mintings likely took place during the Sertorian Wars to pay the Roman troops.”

Best thing thus far

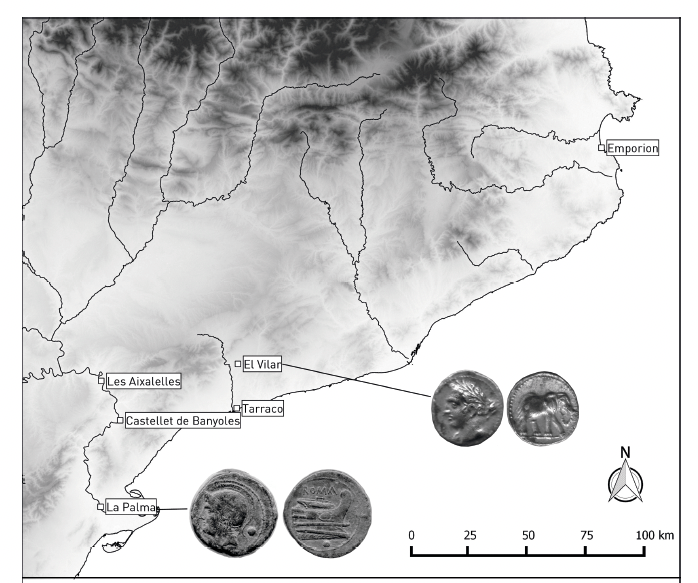

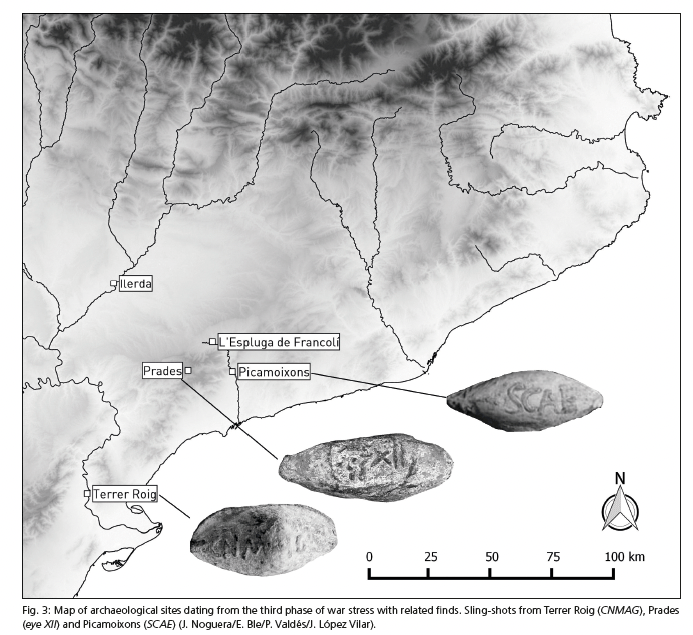

- Noguera, Jaume, Pau Valdés, and Eduard Ble. “New perspectives on the Sertorian War in northeastern Hispania: archaeological surveys of the Roman camps of the lower River Ebro.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 35, no. 1 (2022): 1-32. [on file; full text available through Google scholar]

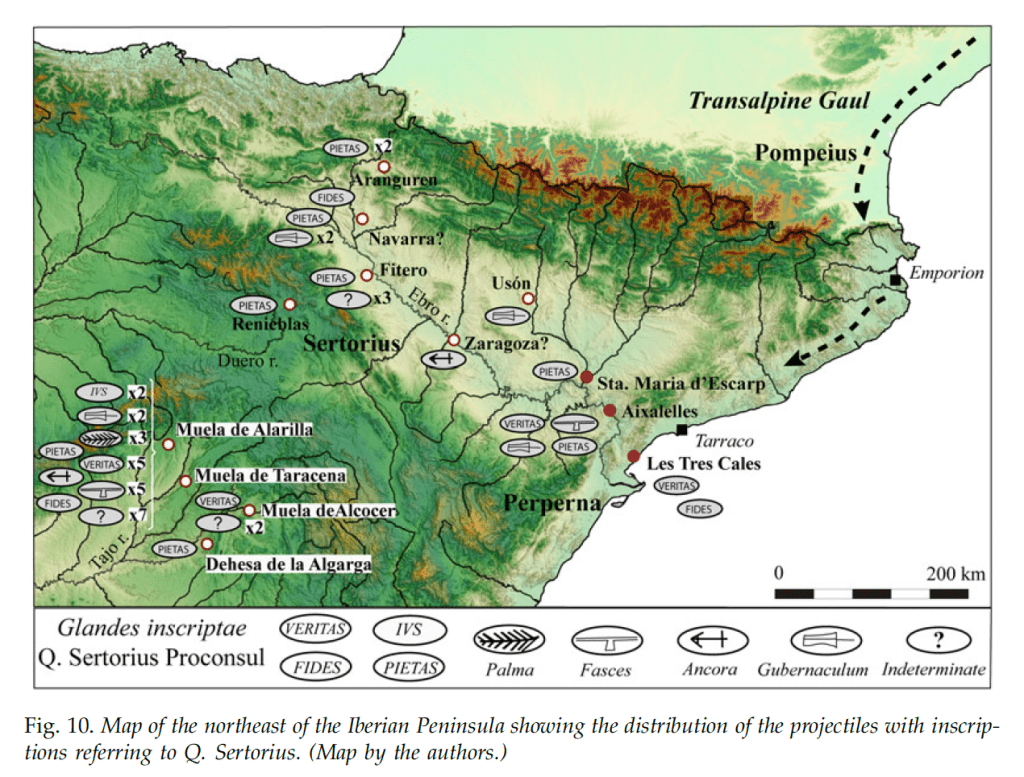

I’m in love with this article. You should read it for so many methodological reasons, and of course the sling bullets (glandes). I’m not surprised by the presence of Fides or Pietas for legitimating messaging, but Veritas and Ius really do feel like a slightly different rhetoric. I want to think much more about them. The fasces also surprise in this context. Not because the imagery is unknown but because the ‘audience’ for these messages seems to be a lower social order and I want to think more about how they would have received this iconography. I suspect in the first instance we should connect it to the use of PRO COS for Sertorius himself and be a statement that HE is the real Roman not the Sullan party.

On Pietas:

- Lloris, Francisco Beltrán. “La «pietas» de Sertório.” Gerión 8 (1990): 211-226. [full text available via google scholar]

I bet I can work these fasces into my talk by way of this coin of c. 82 BCE (RRC 372/2; Mainz specimen). Perhaps a stretch but I may do it for fun and contextualization.

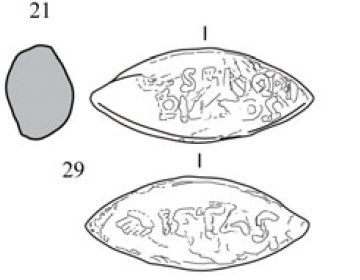

Glandes illustrations

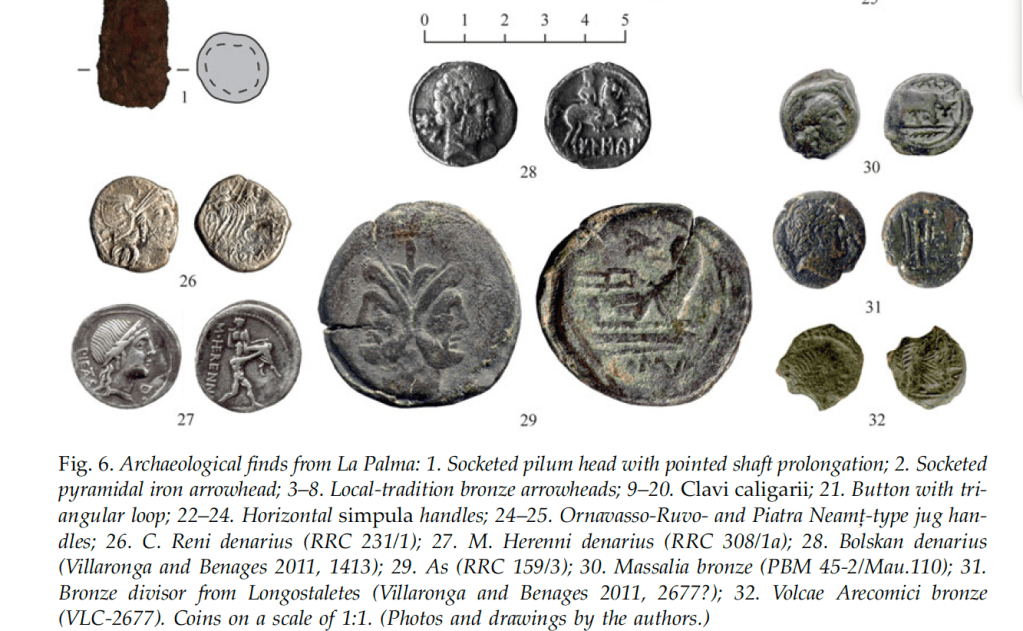

Coin illustrations

So now I’m obsessed with Noguera’s scholarship and getting a little off track, but I’m going to run with it a little longer….

- NOGUERA, JAUME, P. Valdés, EDUARD BLE, and JORDI LÓPEZ VILAR. “Tracing the Roman Republican Army. Military Archaeology in the Northeast of the Iberian Peninsula.” In Limes XXIII. Proceedings of the 23rd International Limes Congress, Ingolstadt, vol. 2, pp. 277-90. 2015.

Look at that glorious Punic shekel with an elephant and young Hercules/Heracles/Melkart with ARCHAEOLOGICAL context. I’d love more of that.

I really like the idea that this glans may have an eye on it. V fitting from an apotropaic perspective. Incredible that there are 82 glandes from Picamoixons with SCAE. I’m curious how we are confident that the CN MAG bullet is from a 49 context not an earlier one, say from the Sertorian war. I’m guessing topography of the war and/or find context. I must pull the original publication to see how firm the dating is.

- López 2013 · J. López, César contra Pompeyo. Glandes inscriptae de la batalla de Ilerda (49 aC). Chiron 43, 2013, 431–457.

This older publication takes a wider geographical area as its focus and thus remains still useful, esp. the appendix of all the glandes he knew at time of publication from the Iberian peninsula:

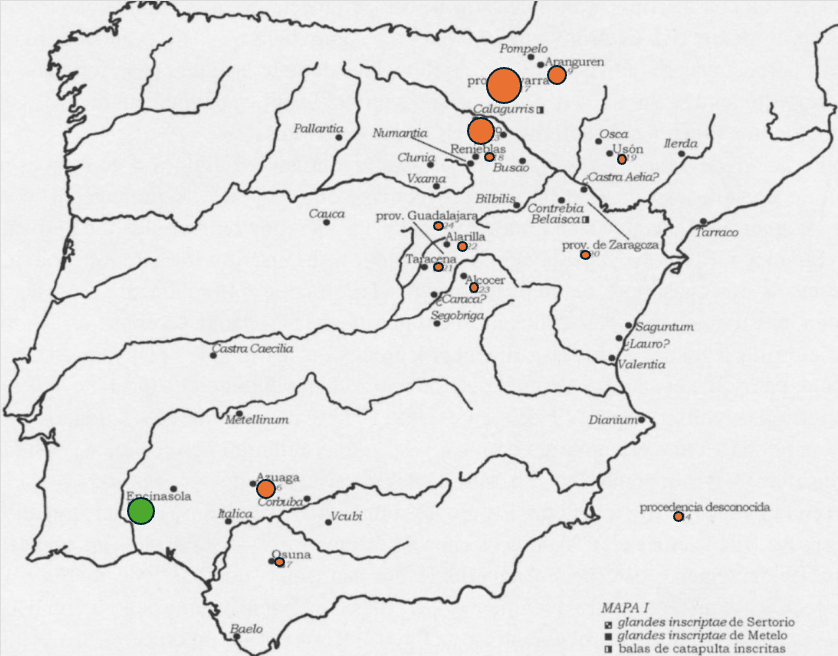

- Ariño, Borja Díaz. “Glandes inscriptae de la Península Ibérica.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (2005): 219-236.

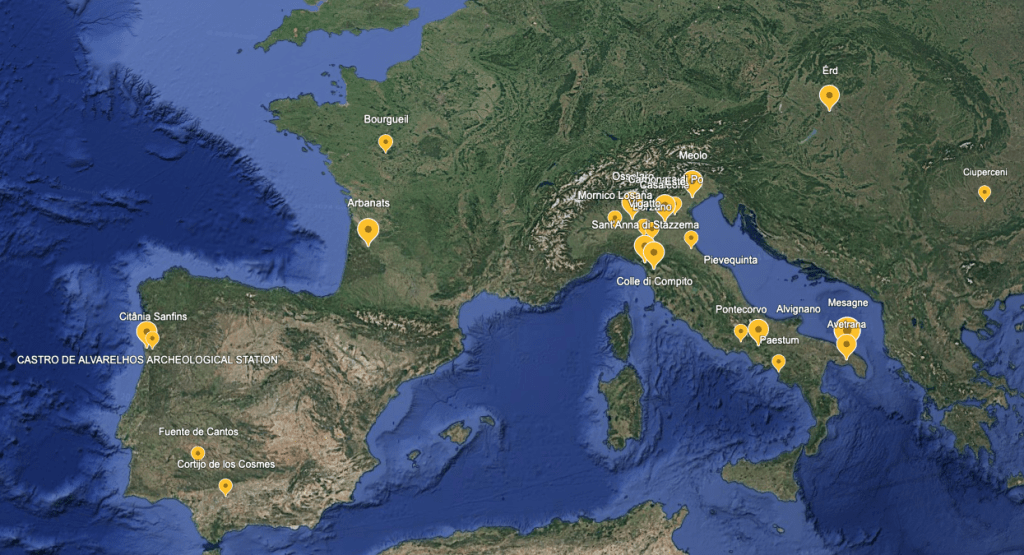

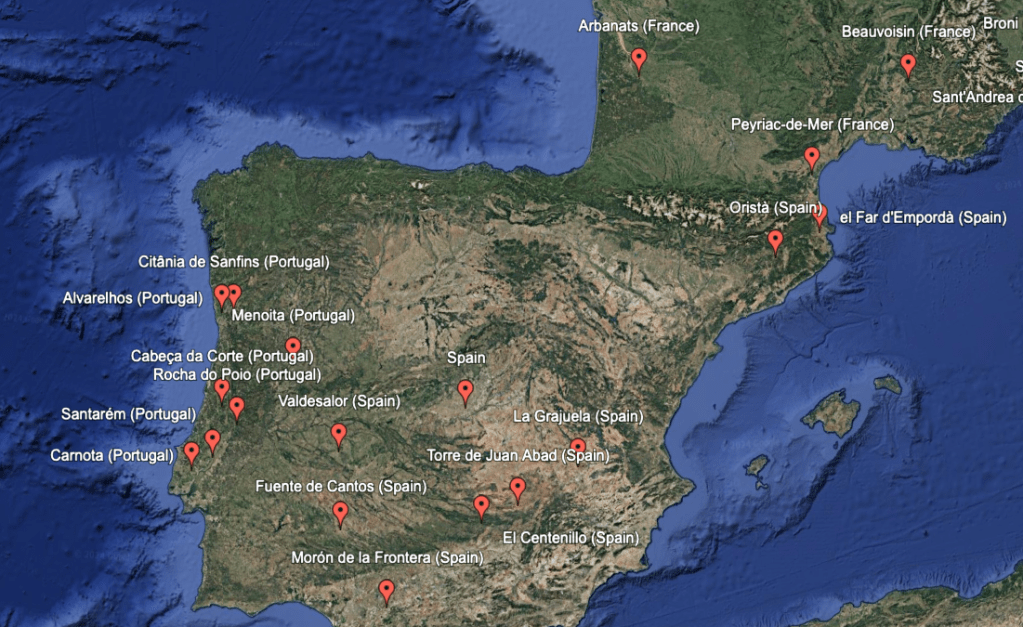

I’ve modified here his map to use orange for Sertorius, green for Metellus. Dots are also scaled to number of finds in general area.

No. 2 below sould probably be re read as [Ve]ritas

likewise no. 4 below should probably also be corrected to Veritas, instead of liberitas.

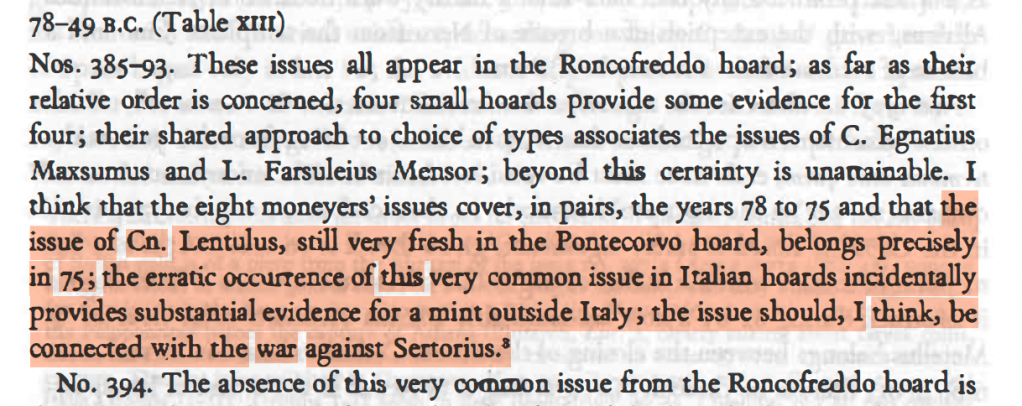

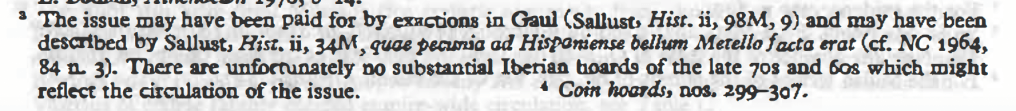

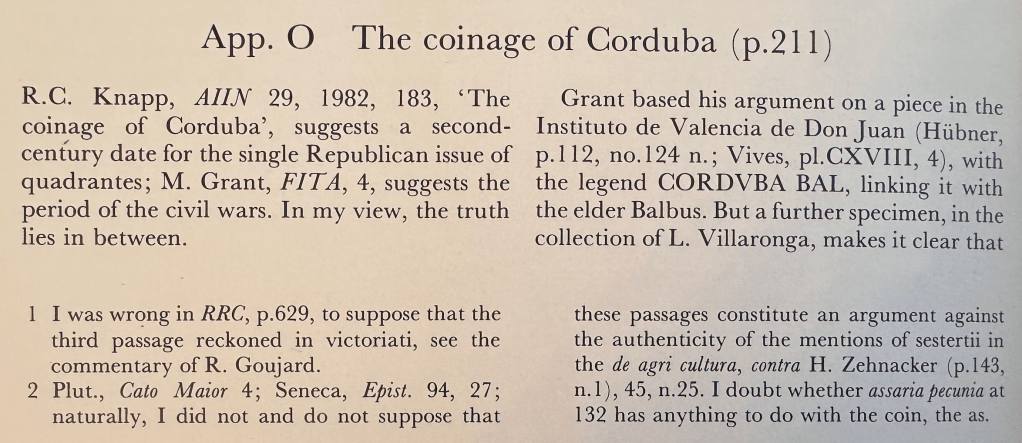

Crawford on Sertorius

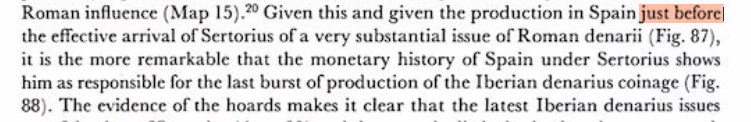

Two points of interest in this second paragraph of his preface (p. xiii). 1) Crawford seems in no doubt that the Iberian Oscan coins are both denarii and made by Sertorius, and 2) he does not see them as ‘real’ Roman coins, thus de legitimating Sertorius’ own claims.

p. 82

Lockyear says this issue is somewhat later in the series (2007: 97). Crawford in connecting this issue to Sertorius seems to have been following Grueber in BMCRR which has these as Spain 52, 57, 58. This is the distribution map from CRRO for 393/1a (Mattingly dated 1b to 58 BCE cf. 2004: 285, but this is not yet proved in my mind).

To get a better idea of the likelihood of such a connection. I only plotted hoard with more the four specimens, removing all the hoards from the visualization that have 3 or less coins of this moneyer. Bigger dots been more coins found at that site (extra-large >100 (only Mesange), large > 10, medium > 4, <10).

Most of those with more than 10 specimens don’t close anywhere in near the dates of Sertorian War:

I think the Pontecorvo hoard is something of a red herring. And I’d point out the complete absence of finds from the Ebro region. So I’m going to disagree with Crawford on this one.

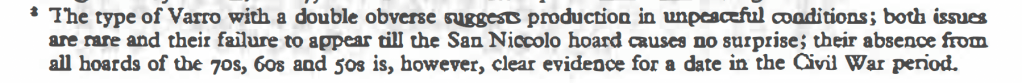

P. 89 & 92:

I agree with Crawford that these coinages are likely from the later civil war and have nothing to do with Spain, but the place of minting might have clues in the new RACOM data. I wonder about the footnote comment about double headed coins associated with unpeaceful times of production. Stannard is now the go to guy on this topic (first article, second article)

P. 370-371

Under discussion of bronze series RRC 355 (c. 84 BCE) Crawford comments that “Salinator reappears as Legate of Sertorius in 81 BCE.” The Prow of these Cinnan Era asses are marked DSS, similar to SC. Meaning they were struck according to the wishes of the Senate.

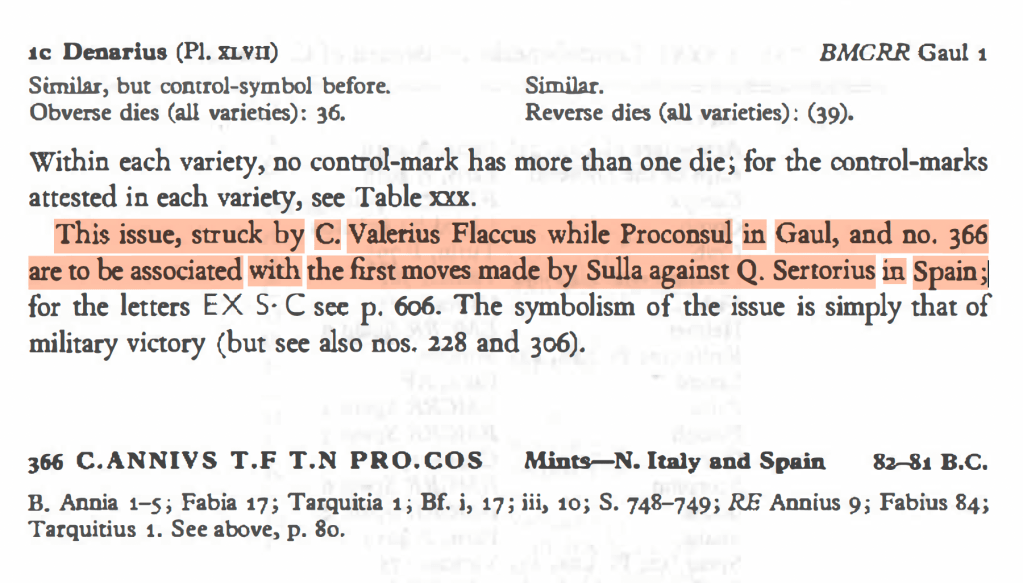

P. 381

RRC 366 is certainly to be associated with the efforts against Sertorius, but I’m less convinced about RRC 365. I see no specific evidence to support this conclusion. I’m inclined to see C. Valerius Flaccus as a more independent actor at this point, but I’m open changing my mind on this.

I looked at the hoard data for 365 focusing just on the Iberian Peninsula and the south of France. It certainly supports minting near Massilia, but we don’t know where the so called Spain hoard (SP2) was found (hence it is just plotted in the center). To associate it with the Sertorian War I’d hope to find many examples in local regional museums of Ebro river region. I’d say jury is still out.

By contrast even without my putting dates on the map you can see that RRC 366 has a much broader representation in Iberian hoards, such that I’m not sure I’d connect them so closely as Crawford suggested:

P. 386

The Konrad article mentioned at the top of this far too long post is an important intervention to these traditional views. There are clearly many different hands carving this complex issue. See new post for more on the deity of the obverse (Aequitas).

I don’t think RRC 393 has anything to do with Sertorius. The interest in the Genius of the Roman People in the early, mid first century BCE still needs explanation. I’m not always one to go in with looking for family connections but I would not rule it out. I wrote about these types in a 2010 publication but should come back to them (PDF link).

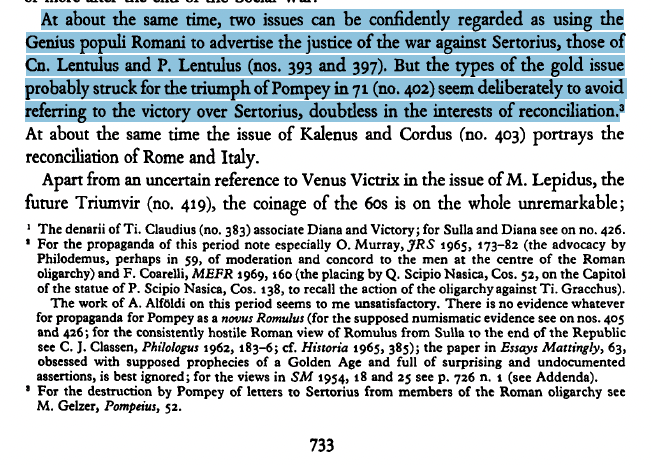

P. 413 revisiting the RRC 402/1 aureus:

Here’s my previous writing on this topic in response to Kopij NAC 2016, 106-127. I’m still on the fence on the dating of this issue. I’ve checked Suspene et al AVREVS and they don’t seem to have tested it. A great shame but understandable given no specimens to my knowledge are available in French public collections. It might be possible to test the BM specimen if i wrote a grant. Maybe in the fullness of time I’ll put this baby to bed that way (I have aspirations to do the same with the XXX oath scene gold of which I personally question the authenticity…). I also am longing for a better picture of the Bologna specimen (That on the website is so low res). The better picture is necessary to confirm whether or not the obverse head is wearing an earring as it appears on the BM specimen. Bologna is die linked to the RBW specimen in private hands (Schaefer archive link). I’m a little surprised I don’t have Woytek’s 2015 chapter on file as PDF nor do I own the RBW Fides volume to which I contributed but at 275 bucks, I just decided to ILL request the chapter. More after I read that chapter. I assume Woytek still holds to his 2015 views as he cites himself in AVREVS but I may need to double check that…

Much Kopij’s argument rests on later epigraphic parallels cf. RRC 446 and RRC 447 and the MAGN PRO·COS legend. I think I may need to review the use of PRO COS for this conference paper. We have the Sertorian Sling Bullets above, we have RRC 402, AND the earliest (I think) use of PRO COS on coins is for Annius (again never elected consul) RRC 366. This is a constitutional moment of crisis and this new power structures different from previous pro rogations is coming out. There must be something newer and more satisfying than Lintott 1999 on this:

P.637- 638 (volume 2)

My forthcoming RACOM paper with Sharpless and Lockyear will help flesh this out a bit, but we know that the amount of striking in the Social War/Civil Wars 91-79 ish was so intense that these coinages dominate the hoards down to the crossing of the Rubicon. This intersects with my paper I was delivering all over the place last fall (ANS long table version).

So I disagree with the GPR stuff as mentioned above. I’m not at all sure reconcilation was a big priority but perhaps footnote 3 needs chasing (see below). RRC 403 is read best in my mind as explain the correct hierarchical relationships of Rome and Italy. Again discussed in my 2010 piece (PDF link).

So that gets us through Crawford’s RRC comments. This leave his more discursive treatment in 1983. As this is less widely available I provide a PDF.

This is so strange I think we all assumed Crawford knew RRC 366 (Annius coins is FOR the Sertorian war not BEFORE). I wish he elaborated on this dating. I’ve also written to Clive Stannard to ask about the coinage struck by L. Appuleius Decianus, Q. and whether he agrees they have anything to do with the Sertorian War.

I’ve also asked about the the Cn.Iulius issue of quandrantes from Corduba. Recent sales catalogues give a date of 49-45 BCE. Crawford wants it struck for Metellus in the Sertorian War, and new RBW ANS catalogue lists the type as second half of the second century BCE, but the older ANS specimens are listed with a date of 100-40BCE. I think I like the late dates (Caesarian) best on stylistic grounds but that is just a hunch. Total the ANS has 46 of these! 14 in the BM. 13 in Paris. Surely there must be a systemaic study of these coins there are so many!!

Crawford also suggests that the coins of Valentia can be associated with Sertorius (at least in part).

The inspiration of these is RRC 265/1 (early 120s?), but the type was revived under Sulla (Cf. RRC 371/1) and in an unpublished paper of Acton 2013 deriving from the ANS summer seminar it has been shown through die links that at some Roma types are linked to Apollo reverses.

The design was also copied at Paestum. I ‘ve a little in my 2021 book on this.

Crawford concludes that Iberian silver coinage ends with the Sertorian War and an assumption this was Roman policy because of the association with Sertorius.

- Antela Bernárdez, Ignacio Borja. “Anio, Fanio y Tarquitio en las Guerras Sertorianas.” Latomus 76, no. 3 (2017): 575-593. Doi: 10.2143/LAT.76.3.3275127 [Jstor]

P. 575

…probablemente autorizado con poder proconsular. La autoridad con la que Sertorio se presenta en la Península ha merecido una intensa discusión…

Ok. This is interesting. The implication is that although Sertorius was never Consul it was the Cinnan Senate in Rome that authorized him as ex praetor to serve in this capacity in this region. This may tweak how I see the sling bullets.

The authors start from Badian’s arguement that Sertorius was ‘offiical’ governor of both provinces and that Annius was his designated successor in both. A tidy picture, but can it be proved?

- E. Badian (1964), Notes on the Provincial Governors from the Social War down to Sulla’s victory, in E. Badian (ed.), Studies in Greek and Roman History, New York, p. 71-104.

P. 576

… y siguiendo a Brennan, podemos considerar a Anio también propretor, a pesar de que en sus monedas se designe como proconsul …

I don’t see Brennan making this claim of Annius, but perhaps my reading hammered by the language barriers. What I do notice in Brennan’s text is the consistent legal framework under both Cinnan and Sullan regimes of sending ex-praetors out as proconsuls, not just Annius and Sertorius but also Fufidius and Calvinus (cf. Thermus too!). I These all help contextualize Pompey’s extra ordinary grants of imperium.

I’m also note of how Sertorius and the Marians are associated with Africa and wonder if this is party of the reason for the Elephant headdress on RRC 402.

Here’s Brennan 2000: 505-507.

From here Brennan continues talking about Pompey being sent to Spain, but I’m going to continue with my reading of Antela-Bernárdez 2017 instead.

… si bien la primera serie de la acuñación tuvo lugar en Roma, probablemente por parte de Fabio, la segunda debió emitirse en Hispania, quizás después de la expulsión de Sertorio de la Península y con el objetivo de financiar un nuevo reclutamiento de tropas que permitiese a Anio asegurar la posición ganada. Por ello, no es estrictamente necesario interpretar que ambos hayan ejercido el cargo de forma simultánea, y quizás en un momento dado uno de ellos fue reemplazado por el otro …

For one quaestor to succeed the other Annius would have had to be prorogated and the quaestor replaced in the new year. Brennan’s re construction doesn’t allow this as it only has Annius there for 81 and two new commanders there for 80, Calvinus and Fufidius.

P. 577

…No obstante, algunos autores han querido considerar a Anio como un representante de la corriente política moderada, intermedia entre los dos bandos enfrentados…

Was Annius a moderate or a middle ground? I’m not so sure. Sulla needed to accomplish two things. 1) ensure no more defections, 2) ensure no oppportunistic power grabs. My guess is that Annius was loyal and just good enough not to mess up the campaign or take too much independent action. (I didn’t type “mess” the first time).

Esta hipótesis explicaría la iniciativa sertoriana de visitar otros focos de posible soporte marianista, y relativiza la versión que argumenta la huida de Sertorio ante la presión militar de Anio

I like this revisionist idea that Sertorius was looking to broaden his base rather than cede territory, but I’m not sure we can prove it either way.

P. 578

Continues same speculation

… y añade Plutarco que este grado de confianza era posible “por aquellos que habían estado con él”. La referencia

puede hacer mención de una relación anterior entre Sertorio y algunos Lusitanos que hubiesen estado enrolados como auxiliares en el ejército de Tito Didio…

The text goes on to say this is an unlikely reading of Plut. Sert. 6.9.

P. 579

Turns the question the problem of the quaestors saying Konrad and Hinard reached the same conclusions: Fabius is the Sertorian, but Tarquitius is not the same as the Tarquinius Priscus from the texts.

- F. Hinard (1991), Philologie, Prosopographie et Histoire à propos de Lucius Fabius Hispaniensis, in Historia 40, p. 113-119.

Says next pages will lay out Hinard and Konrad’s arguments.

P. 580

…Fabio Hispaniensis debería haber obtenido el cargo de pretor monetal bajo la aceptación de Sila….

What does pretor monetal mean? He’s a quaestor, just as it says on the coins…. Maybe a language/terminology issue on my side.

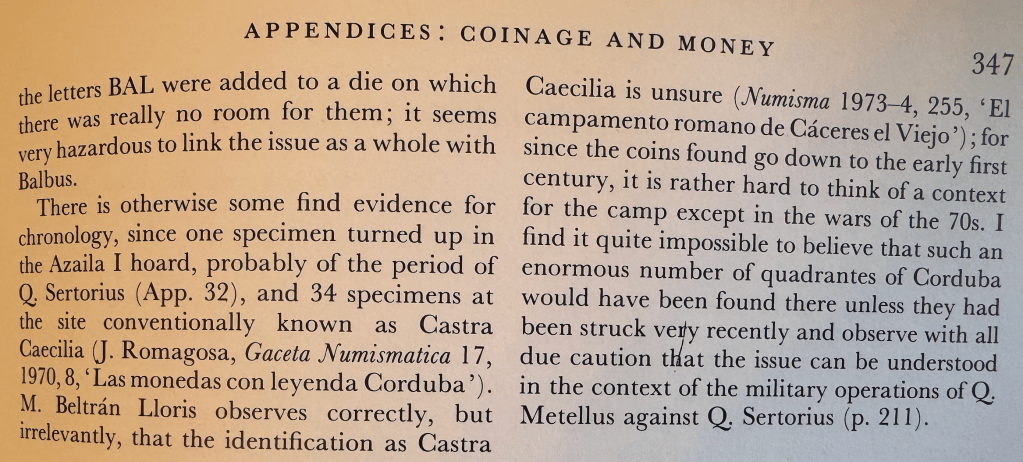

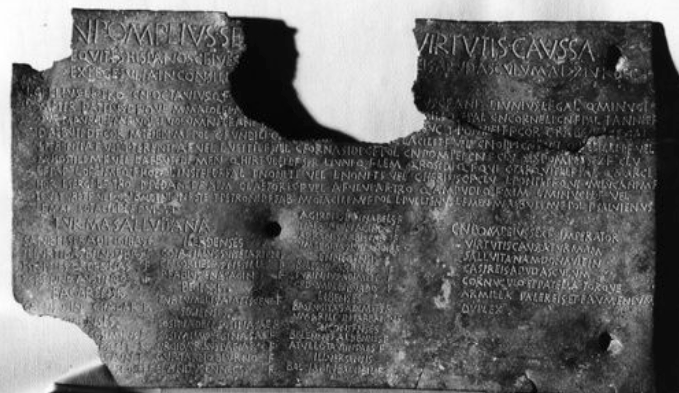

Critiques Konrad’s differentiation of Tarquitius from Tarquinius as these may be variations of the same name. Reminds reader that Konrad draws support from the Tarquitius spelling on the Ascoli Bronze (line 9 near right hand side).

I agree spelling variations are not definitive proof. Including bronze just so I remember it.

… Konrad acepta la posibilidad de que Fabio hubiese sido primero elegido como pretor en Noviembre 82…

Now I’m really confused by the term pretor for quaestor.

Hinard no considera aceptable tal hipótesis, a la luz de las implicaciones de la proscripción de Fabio, que imposibilitaría que un individuo susceptible de ser considerado enemigo de la República tan sólo unos meses antes hubiese sido elegido antes para un cargo como el de pretor

I don’t share Hinard’s concerns the proscription lists could be arbitrary and cruel. And I don’t find the arguement that their were two Fabii Hisp. likely at all. DPRR keeps them as one individual. The date of his election is must have been 82 for 81. That said Hinard is correct that some families tried to have members on both sides of civil wars not just in the Sullan age but also later under Caesar.

P. 581

Y sin duda es esta situación la que nos hace pensar que, efectivamente, en ambos casos estamos ante los mismos personajes.

Now we come to the authors’ own view that both men known from the coins are the same two men known from the texts. I’m open to this idea. And convinced on Fabius and Tarquitius is possible… The speculative arguement that because no Fabii held the consulship between 116-45 means the family was Marian seems weak. I’m curious for the evidence of Fabian engagement with the found of Valentia. Is the arguement based on the borrowing of a coin design from Q. Fabius Maximus? (see above.)

P. 582

Sabemos, ante esto, el papel destacado de Valentia en el bando Sertoriano, según atestigua la epigrafía. Por otra parte, los vínculos de la gens Fabia con Lusitania parecen también evidentes a la luz de la numismática y de la participación de éstos en la lucha contra Viriato.

The footnote to the sentence is:

- H. Gallego franco (2000), Los Sertorii: Una Gens de origen republicano en Hispania romana, in Iberia 3, p. 243-252.

I many need to check for epigraphy. Odd the footnote for the second is only to Florus 1.32.17 [sic], nothing about coins as mentined in text.

At last Fabius Maximus had overcome him also; but his victory was spoilt by the conduct of his successor Popilius, who, in his eagerness to finish the campaign, assailed the enemy leader, when he was already defeated and was contemplating the final step of surrender, by craft and stratagem and private assassins, and so gave him the credit of seeming to have been invincible by any other method. [Florus 1.33.17]

The authors suggest that Tarquitius’ name may indicate an Etruscan ethnicity. I was sceptical but the six epigraphic attestations of the gens pre 1 BCE make this seem possible.

I also ran the gens Tarquinius and got two results, one from Ceveteri and one from Rome.

I”m less sure I believe in the Etruscan-Iberian connection pre existing. I don’t believe connection between Tarquitius and Sertorius can be easily traced to the Social Wars. Sertorius was in Cisalpine Gaul, Tarquitius was at Asculum and with Pompeius Sextus’ army.

P. 583

Speculates on Annius’ disappearance after the Ebusus incident and a power vacuum into which Pacciecus steps. I need to go back to the primary sources here to refresh my memory.

P. 584

Annius is not among the four generals whom Plutach mentions Seritorius facing: the authors suggest Annius perished in the course of his campaign. Argument from silence. The question they say is not why where they elected (Hinard’s question) but why did they defect?

P. 585

Did Sulla really control all elections in 82 BCE the authors ask or just the consular ones?

P.586

The authors question whether we can trust Sallust’s testimony regarding proscriptions of Fabius. I think we can.

[And this raises in my mind when Fabius entered the Senate…]

P. 587

Accepts identity of obverse as Anna Perenna. I don’t.

The authors cite:

- R.D. Woodard (2002), The Disruption of Time in Myth and Epic, in Arethusa 35, p. 83-98.

I’m not convinced by Woodard’s methodology to support his (Indo-Aryan origin) theories. On Anna Perenna, I’ve created a new post.

P. 588.

Suggests the coin is pointing to Annius setting out for Spain in March 82 BCE (!) (because of the date of Anna Perenna’s festival in that month!). The authors propose a series of events where Sulla takes Rome in November 82 BCE and is read as written Annius sets out before this. OR, if I am charitable and allow my reading of the Spanish might be wrong that Annius sets out just after Sulla takes Rome but before the Ides of 81 BCE and evokes Anna Perenna to legimate leaving before the campaign season’s traditional start. I don’t find either logical.

Habitualmente, sin embargo, se ha presupuesto que la acuñación de Anio tiene lugar con posterioridad a su enfrentamiento con Sertorio, y que la iconografía de la misma haría referencia a su victoria sobre los sertorianos en los Pirineos

I don’t think I or those I read have assumed that only that victory (even anticipated) is appropriate for any War issue. RRC 366 is minted in multiple mints that seems clear precisely when and where remains to be seen.

P. 589

Suggests that caduceus and scales refer to commercial trade and how recent war events may have effected trade and commerce. Also suggests that land seizures by Sulla for his troops in Etruria might have been reason for Fabius and Tarquitius’ defections presuming these negatively impacted their families.

De este modo, podemos contraponer a los supuestos “piratas” sertorianos, en realidad comerciantes, que apoyan a Sertorio, con aquellos comerciantes a los que la acuñación de Anio parece hacer referencia. Por lo tanto, la lucha entre

Anio y Sertorio por el dominio del Mediterraneo occidental puede entenderse en suma como una muestra más de la existencia de un conflicto de competencia entre dos grupos de comerciantes, resultado de los destacados intereses mercantiles (como los de la isla de Ebusus), estando cada uno de ellos vinculado a uno u otro de los bandos contendientes durante el conflicto sertoriano.

Liv said: I suspect in the first instance we should connect it to the use of PRO COS for Sertorius himself and be a statement that HE is the real Roman not the Sullan party.

This is my understanding of Sertorius, and why I am continually surprised no coins minted by/on behalf of Sertorius as ‘the true Roman’ have come to light. Coins would have been particularly important for him to purchase food and fodder, as well as to pay soldiers, wagon drivers, and others providing logistics support. Coins representing “PRO COS” would be a great way to spread the Sertorian message widely across the province.