There is a significant literature on constructions of race and ethnicity and their intersections with ancient slavery and the body of scholarship continues to grow. (One can read Eric Gruen on this subject, but I’d recommend the work of Emily Greenwood and keep an eye on the future work of Sarah Derbew). I’m no expert on the subject and my primary interest in the topic is with regard to reception studies: how the model of the Greco-Roman past was and is used by Europeans and other colonialist states.

All that said, one of my pet-peeves is the casual dismissal of skin color as a factor in ancient slavery, something we often hear in classroom discussion (cf. duBois 2009: 31). It was not the only factor and not always a factor, but it was a component and intersected directly with the potential futures for a slave. A key case in point:

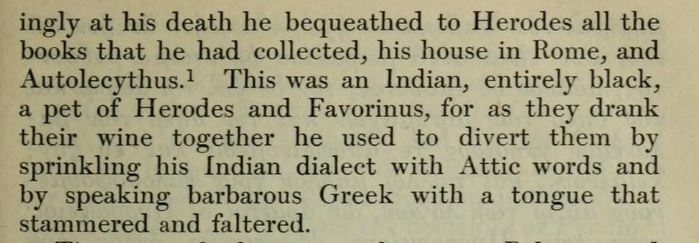

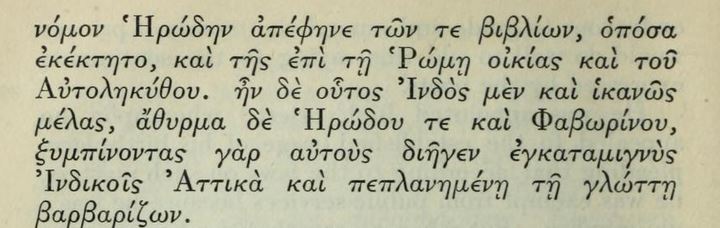

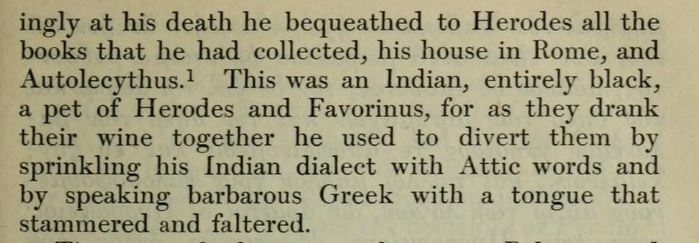

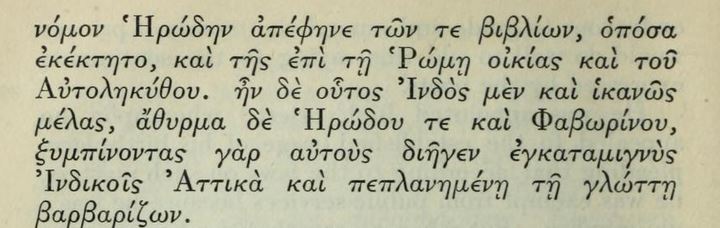

This is from Philostratus’s Life of Favorinus. In this period, a beloved slave might reasonably expect to be freed upon the death of his/her master. Not this one. Autolecythus (‘he who carries his own oil’) is seen as a fitting accompaniment to the bequest of a library and a house. Philostratus characterizes this slave in five ways:

- A servile name denoting a common servile action related to Greco-Roman athletic and bathing culture. This should make us remember illustrations of dark skinned (often ithyphallic) bath attendants in art of the high empire and related iconography. (Example 1, Example 2, Example 3).

- His ethnicity as an Indian.

- His skin color. Note especially the emphasis on the totality of his darkness.

- His role as an entertainer in a sympotic context. A role that has long been sexualized in Greco-Roman culture.

- And his hybrid linguistic status. Not bilingual, but an ambiguous mixing of the two languages together. Philostratus may be here playing with the idea of mixing and ambiguity in Favorinus’ own identity as a ‘hermaphrodite’ or ‘borne eunuch’. The ambiguous man gives as a gift another ambiguous man. Notice it is not any Greek that the slave uses but specifically the Attic dialect, the dialect of the second sophistic. There is surely an interplay here between the Indian reputation for wisdom and the association of Attic with the language of Greek learning and philosophy.

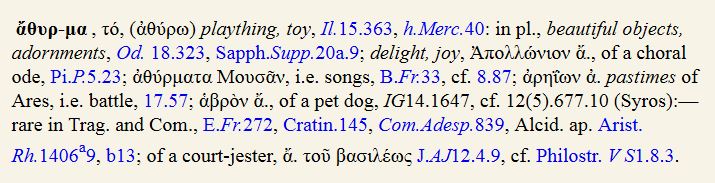

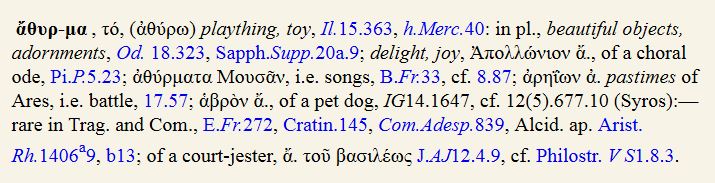

And then there is the problem of the word ‘pet’. Is Philostratus animalizing Autolecythus? Or is it just the translator who has done this? Perhaps a bit of both. The latter for certain, but perhaps it is a fair if uni-dimensional reading of the Greek. Here’s the Liddell and Scott entry:

Jester might be the most neutral translation, but notice that it is also a term that is used of objects desirable on pleasurable aesthetic terms, and perhaps even on sexual grounds. Its semantic range of meaning is as ambiguous as the identities of both Autolecythus and Favorinus themselves.

Is Philostratus asking his reader to see Autolecythus as reflection and further characterization of his master’s identity? I would say so. And this only further erases the individuality and personhood of this particular slave.

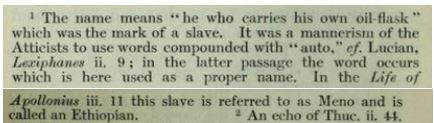

We can see more of the translator’s reception of the text in this note:

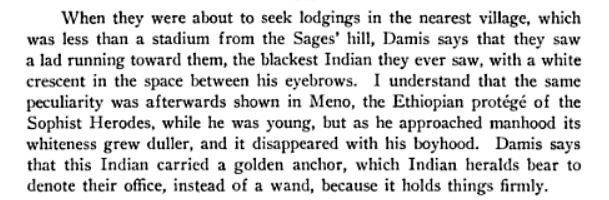

He assumes the that Meno and Autolecythus must be the same. Here’s Philostratus on Meno in his Life of Apollonius:

I see no need to assume that they are one and the same individual.

This is post came about because I’m teaching gender ambiguity in Antiquity this afternoon and I wanted to include Favorinus.

12/11/15: This is a low traffic blog, rather by design. It is just where I collect my thoughts on academic matters that are distracting me from my other tasks. However, this post seems to have been circulated on some more high traffic facebook/twitter post. I’m curious where and why its generating clicks. If that’s how you came to read this, feel free to leave me a comment letting me know! I hope you enjoyed what you found. This may turn into a longer conference paper or publication in future so feedback is always welcome!