Update 3-2-23: Blog post summarizing whole of conference

adventures in my head

The jetlag is rough this morning. I’m three cups of coffee in and barely moving. I was going to skip this bit of journaling but I need to get the brain in gear if I’m going to conference properly this afternoon and tomorrow. Must try to get to bed a little earlier tonight.

Yesterday was the Villa Guilia and Palazzo Massimo. Starting with the latter as it is clearer in my mind.

I was not as in love with sculpture as I have been in the past. It felt too familiar and I moved relatively fast through those galleries. The frescoes held my attention for a very long time. I found myself wondering if there is a literature of human activity in Roman landscape painting. Most all the landscapes seemed to have been conceived as religious or sacral. With acts of piety towards shrines being the most typical social and even inter-generational activity. The landscapes also included rustics, figures marked as other by the disfigurement of their bodies through hard labor: rustic labor being the second most common human activity in these painting. One swine herd in particular captivated me. I cannot quite say the rustic world is romanticized in these images, as we might surmise from bucolic/pastoral poetry. The architecture in the landscapes is varied yet relatively formulaic (surely some colleague has catalogued them and created a typology?!).

Most of the panels on display with such landscapes came from elite houses, but one set was from a private columbaria. The decorative bands were between the rows niches for the funerary urns. Overall these were more varied but landscape was common. YET so are nilotic scenes with pygmies, another type of landscape genre with its own conventions. The contrast between the two imaginary worlds the idealized local and the distant other was more jarring having them all together.

I spent some time also with the fresco narrative cycle of Rome’s foundation. The lighting wasn’t great but it was still good to go over it scene by scene in person. Thinking back on it now the bands remind me more of the more humble columbaria bands than the frescoes elite domestic rooms. The private columbaria has one band of mythological scenes related to Hercules, perhaps that is why my brain wants to make the connection.

There weren’t any big thoughts at Villa Guila, except the perhaps just the good reminder of how monumental terracotta can really be as architectural and sculptural elements. Mostly I was just loving seeing traces of myth and iconography early in Italic history, esp. those that carry through.

For instance, who doesn’t love a pointy hat, which with the Romans we come to associated with priesthood and the apex.

I’ve just checked the program and realized I don’t have to be anywhere until 5 pm. I though I was due at the conference at 2pm. I had best do something with my day rather than sit in my hotel room…

Again I may come back and add more pictures but must press on.

Sitting at a hotel breakfast with a lovely view of St. Peter’s dome, forcing myself to eat some protein to get to lunch. Monday and Tuesday were mostly logistics but this post is to help me remember stuff I saw yesterday.

My hotel is up the via Flaminia. At the Ankara/Tiziano tram 2 stop there are large monumental travertine blocks in the boulevard park. No label anywhere I could see. Curious if we know what structure they are likely to have been from.

Took the subway to the Baths of Diocletian and exited in Piazza Republica and admired in the station there that the flooring for the utility corridors under the baths is exposed with large basalt pavers. Helped me visualize the true scale of the original complex.

I broke down and bought the new catalogue of the epigraphic collection from the museum. A doorstop of a book, but worth it. Things that stick in my mind that I want to read about in the catalogue:

list in no particular order

acorn shaped scale weights, similar to the acorn on coin designs.

A set of well formed well preserved basalt weights similar to those on display in Praeneste

The Mummius inscription from Fregellae

The T shaped pre historic dagger handles in the proto-Latium section: not a perfect parallel to the handle of the t-shaped daggers on the coins of Ariminum and the Eid Mar coin but got me thinking in that direction.

The major warrior burial from Lanuvium (I think that’s where) with a full set of armor and also athletic stuff. The discus thrower depicted on the discus was amazing. The sword was very Falcata like in shape. Maybe I”m wrong to read that symbol as Spanish.

The chapterhouse courtyard with all the displays of Arval Bretheran inscriptions was new to me. I got some nice teaching images with the dates on the calendars. The choice of gods honored with each different emperor was fascinating, as was the ritual emphasis on iron tools and how they were explicitly used not only to tidy up the sacred grove but also to carve the record. I particularly liked that under Elagabalus his grandmother is honored.

In that same courtyard were finds from the villa excavated along the via Anagnina. I was impressed that we know the imperial portrait (very nice pair of Verus and Marcus Aurelius) were from the impluvium/atrium area of the house. The fountain from the same area of the house seems to refer to the days of the week through deities. BUT this raised the question of when the 7 day week entered the Roman mind.

Still the same courtyard, the busts of Geta and Caracalla from the House of the Vestals in the Forum left an impression as well.

Up on what they call the 1st floor (I might have called it the 3rd), where there is all the religious stuff, there is a new to me display on magic. The prevalence of nails and the wider variety of effigies than I’ve seen before was notable. Also a lead ‘book’ with seven pages and obscure iconography was fun. There was also a summary of finds from the Anna Perenna spring. The coin deposits seem to have only started with Augustus. If this is true, perhaps this is also one of his ‘revivals’.

There were also other examples of roof tile graffiti which would provide context to the one with two sets of footprints I use in my courses so much.

I was also intrigued by the letter forms in the script writing esp. the two parallel lines to represent the letter E. Where does that come from.

In the case with the earliest writing there was one clay vessel with three names but that attributed to the potter derived from the name Ulysses.

A few lamps has a green glaze. When did this technology show up in Rome?

I’m sure there is more from there but I’ll add it as it pops back into my mind.

After leaving that museum, I walked down to the Markets of Trajan. I wasn’t planning to go in and my camera battery was completely dead. I was just trying to get enough exercise to help kick jetlag. But the markets had a late closing and how could I resist.

The colossal busts from the forum of Trajan my kids would have loved. My favorites were the lower half of Trajanus Pater (I’d recognize that chin from the coins anywhere!) and also the mystery of the woman with the hair style similar to Agrippina the younger tentatively identified as Trajan’s mother Marcia. These were in shield roundels originally alternating with the Dacian prisoners.

The displays helped make clear how this alternating motif was inspired by a similar visual alternation of shields with heads of gods and caryatids in the Forum of Augustus. Other details from the Forum of Augustus that stuck with me was the gilt foot of a giant Victory and the elaborately carved Corinthian capitals that instead of just leaves have Pegasus leaping forth.

Some how I forgot if I ever knew about the hall of the Colossus with the statue of the ‘Genius’ of Augustus of the back of the left hand portico of the forum of Augustus. The meager fragments are impossibly huge, but the display did a great job especially helping one visualize the wall painting.

The display on the removal of the Velian hill in the 1930s was very moving. The excavation artists were so talented. The video footage was arresting. The little fresco wall panels evocative. The museum book shop was selling large books with photos of the excavations of this period of the forums. V tempting.

From the forum of Caesar, I was reminded that the cupids stealing the arms of Mars so common on sarcophagi also had political resonance. Also what’s up with all the cupids killing bulls?!

Ok that’s what I remember. Maybe this evening I’ll upload some photos to go with this post.

Now off to the Villa Julia.

This gold and glass representation was found during the building of the line C subway in Rome and now widely reported in the news.

original media photo

It is being reported as representing Roma, but it could just as easily represent Virtus. This issue comes up again and again (old blog posts: a Lararium in Stabiae, RRC 403/1, Roma as Amazon, Literary treatments). There is some stuff on this in my coin book too.

In art history the debate over Virtus or Roma usually plays out in the interpretation of imperial monuments

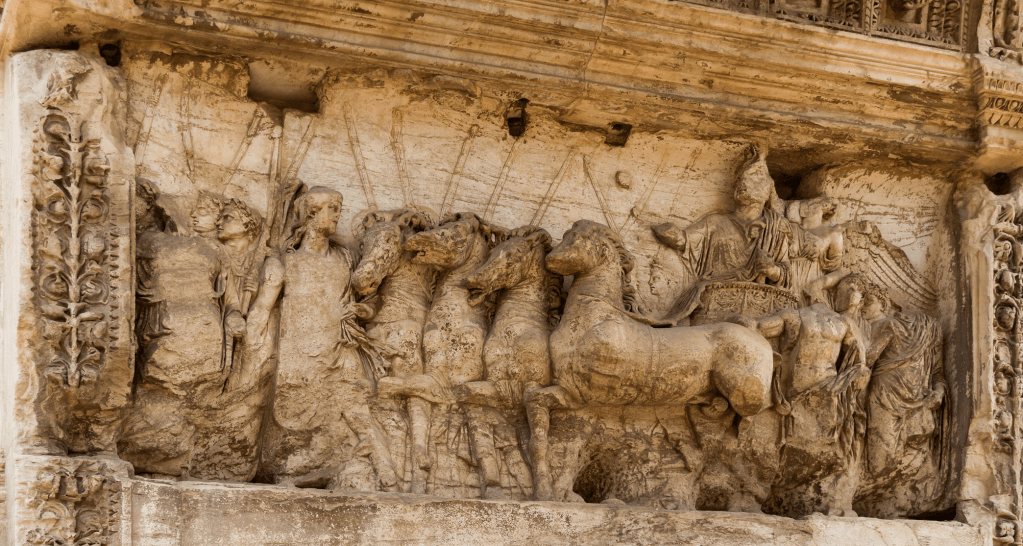

Who holds the emperor’s arm here?

Who leads the chariot here?

There are some parallels in coin images but none exact, no triple crested helmet, no spear in front of the bust, no emphasis on bands crossing between breasts (an amazonian element). It looks like on the glass what is typically a shield in such bust representations is just extra drapery.

More than anything the style of the gold and glass reminds me of the artistic style of Contorniates, but I don’t yet own the standard reference catalogue for those. I think it is the long face. I’m not sure if there are any Roma/Virtus contorniates… Must check… (cf. Alföldi Contorniates 77 and p. 26, 10, no spear, Cf. Alföldi, Kontorniat, 70/493; )

The closest parallel seems to be with personifications of Constantinople but no triple crested helmet and it is a scepter instead of a spear.

For the triple crest cf. RRC 329/1

Also earlier post on the helmet type

I also have a strong memory that Miles MacDonald, in his book on Roman Manliness (virtus) talks about this helmet. …

I finished, at least for now, my slides for the conference. It might be a little long but I think I can get through it. I’m not scripting. This feels dangerous and delightful. I want to know my material and speak in an easy conversational style. I’m the fourth speaker on the first day full day (11 am local time next Friday.) To pull off the speaking style I want and make it make sense sans script I will need to be as hyped about the material as I am at the moment. That will take some serious time in in my hotel room the night before and the morning of. BUT I still have the better part of three days in Rome to see stuff. These are the best conference organizers ever: they are flying us in early so we can get over jetlag. So what to see! I have a habit of just seeing my old favorites again and again (I always have new eyes for the stuff.) But I want to make the most of this.

Ideas to break my old habits

Nemi site and museum

2-3 hours by public transport (four transfers: tram, subway, train, bus) or 1-2 hours by taxi (€ 67.30 there plus 27 for every hour I want them to wait plus € 67.30 back, oof!) – this is why I wish my beloved was coming with me to drive me about, I’m so spoiled, and that area is one of which I have very fond memories with him of past travels.

closed for restoration. dammit.

closed for restoration. arrgggggg.

Requires group reservation or reservation to join an individual group on a specific date. This trip not possible but link to what is possible when is useful for future.

Museo dei Fori Imperiali & Mercati di Traiano

Not as high on my list as other things, but it looks like it has changed a great deal since my last visit so perhaps a good stop.

Only by guided tour F, Sa, Su. Could probably make 5 pm Sat tour. 10 slots remaining.

To be continued.

It is very hard work to stop myself sharing all the pretty graphs I’m drawing but I’m resolved to wait until the conference itself to show my whole hand on this data. Yesterday was super productive largely because my quantification of the variation between readings from the same specimen meant that I asked for help from Wayne and learned a whole bunch in the process.

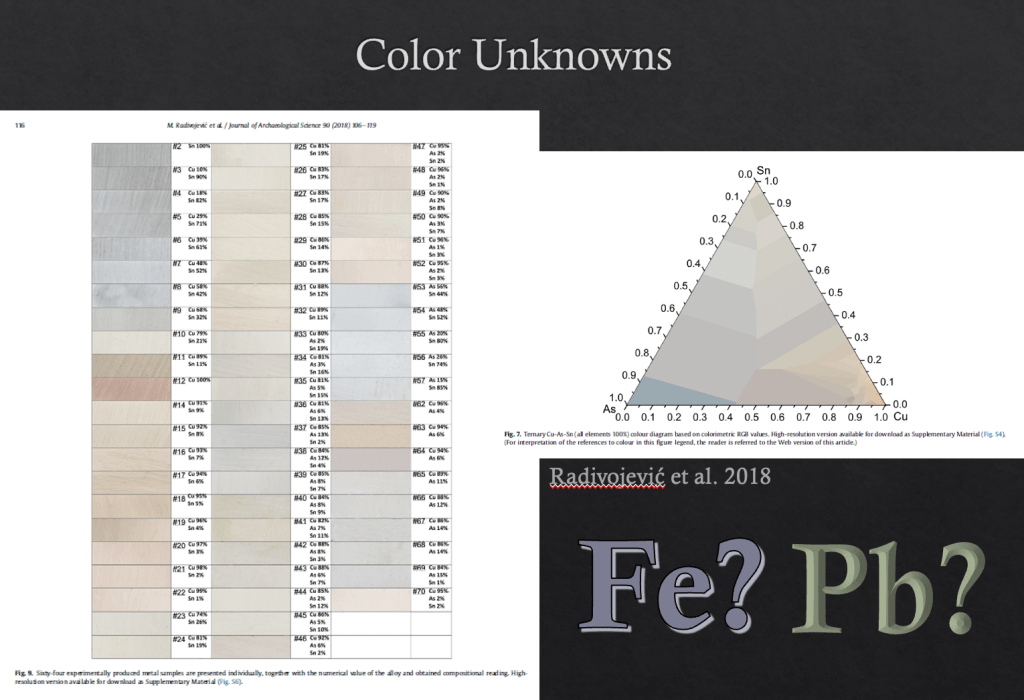

Ternary plots! A bit like that triangle below. This lets demonstrate how the ratios of copper: lead: tin appear in all specimens and allow v clear patterns to appear. 3 axes are way cooler than just 2 and a nice mental baby step towards more multi dimensional plotting stuff like Correspondence Analysis (CA)–that’s the cool type of data exploration used by Kris Lockyear to explore hoards. Unfortunately excel needs a plug in to draw these. Everyone’s favorite seams to be tri-plot. There is a fancy add-in called XLStat but it isn’t available it seems for the version of MSOffice my university gives me. BOO! Maybe I can figure out how to get a copy it looks like a great deal of fun.

Color issues! So I’ve known for a while (see below) that we’re not sure of the original surface look of aes grave, because of the high lead content, but there is some suggestion from unpublished data from the Balkans that high lead may have been used in the bronze age specifically for decorative and ritual objects because of the silvery surface color. This lead me to be v tempted by experimental archaeology to produce a few specimens to test.

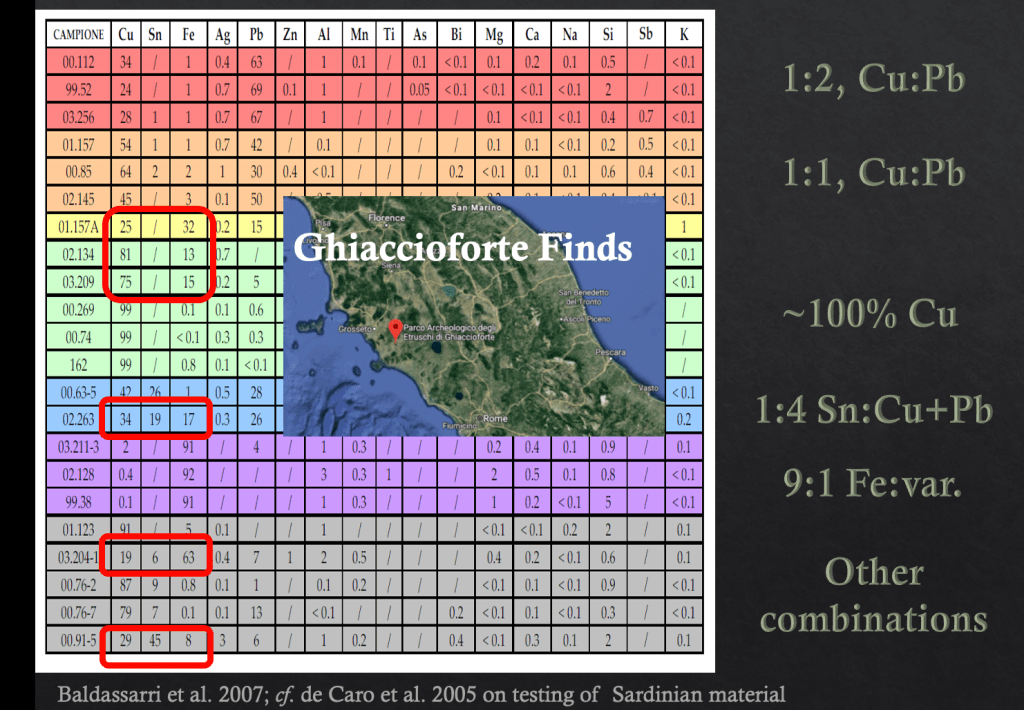

Division of elements into intentional and unintentional! So I’d been mostly doing my thinking about ratios leaving the trace elements in, but this doesn’t account for original intent. There is no evidence they meant to put antimony, silver, iron, arsenic etc… into these things. They are impurities in the ores or bullion used. They tell stories but if what I want to recover is the recipe or recipes the Romans intended they only add noise. Removing them from some of my calculations has made a clearer picture.

Base-12! Ok this inspiration was my own not Wayne’s. Any target recipe was likely in Roman units of measure, likely weight and likely on a base-12 system. So we’re talking uncia and scruples once we get below a pound. This is proving a very useful means of thinking of how the data patterns might fit into Roman intention.

Casting SAND! This I owe to my v practical neighbors who know all about metal for industrial and artistic modern applications. I was running the idea of what it would take to try some experimental archaeology and we got to the material to cast in and we talked through clay and that can explode presenting safety issues as we learn what we are doing, so we thought safest to start with green sand, which means moisture-rich sand and is in no way green in color, NOT to be confused with the geological/gardening green sand. I asked how you make a shape you want and was told you just impress it same as clay. I don’t think this is what the Romans used for aes grave, but I wonder about some other aes formatum/italic aes grave. It would be fine for ramo secco and probably also the bronze shells. The later worry me. None in Haeberlin and I don’t know (yet!) of any hoards with them or site finds, a quick internet search shows Italian metal detectorists seem to turn them up but not sure I want to put scholarly weight on that. They also show up on the market but are nice collectors pieces so no surprise there. Cf. Vecchi 2014: p. 90 figs. 4-5.

It I do try some casting I think I’ll aim for this shell shape to start.

Today’s goal is to finalize visuals and start to make sure sequence of slides tells the big story of why investigating this what I did before, what comes later and what I know now. I want to try to narrate without script.

This is a free writing exercise of stuff rattling around in my brain .

After finishing cleaning and organizing the data of all my scans, I spent yesterday creating scatter plots, bar graphs, and pareto histograms. I explored overall patterns for all cast coinages and whether there are noticeable differences and patterns between the different issues factoring in the different denominations as well. I cannot wait to share all of this here, but I think I best hold back on sharing my slide deck until after the conference. Maybe about Feb 20 I can post here.

Today’s goal is to quantify degree of difference between obverse and reverse readings and ensure my audience can understand why this variation exists.

Short answer: Neither lead nor iron create a true alloy with copper. This means the composition of all aes grave is not uniform through out the individual specimen. There is not a strict purity standard that was or could be enforced given the high use of lead.

Most of the understanding of surface analysis techniques within numismatics derives from the flawed studies of Walker on silver in the 1980s and the robust debunking of those approaches using drilling techniques by Ponting and Butcher. None of this is untrue but bronze as an alloy is another kettle of fish and we need to take our lessons and caveats from bronze specialists not silver. Drilling is still the best way to know what was originally manufactured but given the lack of a uniform alloy throughout the individual specimens even drilling means we cannot know for sure our sample is always representative of the whole.

Is Drilling useless then? Absolutely not! The samples taken can contextualized surface readings and be used for deeper analyses, especially of isotopes. This is shown by historical changes that were noticed in the this study.

Westner, Katrin J., Fleur Kemmers, and Sabine Klein. “A Novel Combined Approach for Compositional and Pb Isotope Data of (leaded) Copper-Based Alloys: Bronze Coinage in Magna Graecia and Rome (5th to 2nd Centuries BCE).” Journal of archaeological science 121 (2020): 105204–.

(Sorry don’t think an open access copy is out there but happy to share a PDF if anyone needs one)

They drilled 5 cast specimens as a point of comparison for later coinages. And, they found really interesting differences between cast and struck. Here’s one visual to give a sense of the value of this work:

But being able to drill 5 specimens is a bit deal! [I must write and ask if they are willing to share data.] There is no way to drill hundreds. So this raises questions of the patterns that emerge. So for instance the drilling of Bars in the BM in the 1980s. The two Bull bars seemed a little lower in lead (18% versus upper 20s). Did this mean a different period of manufacture? A different recipe for the alloy? I might have thought so, but no more. All those bars look just like the aes grave I’ve been testing, high lead, high variation. The question becomes whats a typical versus atypical composition and how much variation seems ‘normal’ or with in tolerance.

And, then there is the question of why any of it historically relevant?

Well for one, I can tell you Roman aes grave is far more consistent in composition than the aes rude found in the region with good archaeological provenance. They circulate together but they are not the same thing.

I’m warmed up. Time to get to work.

I’m still sick and it is for the birds. I do feel I’m on the mend though. But I’ve caught up on emails for the most part and otherwise cleared the decks to really start crunching my data so far and then build this slide deck for the conference in Rome next week. I’m going to keep this short as time and energy are at a premium.

The following article really felt a game-changer for my understanding of what I’m seeing in the data. The lead authors are known to me from a number of their other publications which I often cite, but this one really got to the heart of the matter of intrinsic value. Back in 2006 they had already came to conclusions through their testing that I personally reached back in 2019 with my meteorological work on RRC 14, 18, & 19 (final text, I’ve seen proofs so it should be out later this year). This and their careful thinking about bronze recipes will really strengthen my initial report on my data to say nothing about what the next steps are.

Ingo, G.M. & De Caro, Tilde & Riccucci, Cristina & Angelini, Emma & Grassini, Sabrina & Balbi, S. & Bernardini, P. & Salvi, D. & Bousselmi, Latifa & Çilingiroğlu, Altan & Gener, Marc & Gouda, Venice & Al-Jarrah, Omar & Khosroff, S. & Mahdjoub, Zoubir & Al saad, Ziad & El-Saddik, W. & Vassiliou, P.. (2006). Large scale investigation of chemical composition, structure and corrosion mechanism of bronze archeological artefacts from Mediterranean basin. Applied Physics A. 83. 513-520. 10.1007/s00339-006-3550-z.

Abstract:

A large number of Cu-based archaeological artefacts from the Mediterranean basin have been selected for investigation of their chemical composition, metallurgical features and corrosion products (i.e. the patina). The guidelines for the selection of the Cu-based artefacts have taken into account the representativeness of the Mediterranean archaeological context, the manufacturing technique, the degradation state and the expected chemical composition and structure of the objects.

The results show wide variation of the chemical composition of the alloys that include all kinds of ancient Cu-based alloys such as low and high tin, and also leaded bronzes, copper and copper-iron alloys. The examination of the alloy matrix shows largely different metallurgical features thus indicating the use of different manufacturing techniques for producing the artefacts. The results of the micro-chemical investigation of the patina show the structures and the chemical composition of the stratified corrosion layers where copper or tin depletion phenomenon are commonly observed with a remarkably surface enrichment of some soil elements such as P, S, Ca, Si, Fe, Al and Cl. This information indicates the strict interaction between soil components and corrosion reactions and products. In particular, the ubiquitous and near constant presence of chlorine in the corrosion layers is observed in the patina of the archaeological Cu-based artefacts found in different contexts in Italy, Turkey, Jordan, Egypt, Spain and Tunisia. This latter occurrence is considered dangerous because it could induce a cyclic corrosion reaction of copper that could disfigure the artefact.

The micro-chemical and micro-structural results also show that another source of degradation of the bronze archaeological artefacts, are their intrinsic metallurgical features whose formation is induced during the manufacturing of the objects, carried out in ancient times by repeated cycles of cold or hot mechanical work and thermal treatments. These combined treatments induce crystallisation and segregation phenomena of the impurities along the grain boundaries and could cause mechanical weakness and increase the extent of the inter-granular corrosion phenomena.

—

In other news, I think I have my Nottingham dates to work on the Nemi material in May and my colleague Wayne Powell is coming with me and that means the science end of this work will be able to appear in a co author publication at some point to match my numismatic and historical approaches. He’s a bronze expert esp. tin isotopes among other things. Particularly awesome is his most recent publication on the Uluburun shipwreck and how it updates our understanding of tin trading and community connections. If you like that sort of thing you might check it out.

I’m sick, nothing special, just old-fashioned winter cold. I keep overdoing it before I’m fully well and then backsliding. Not a good pattern. I’m trying to slowly tend to communications and other tasks and nurse this pot of tea.

Anyway, I was looking at Crawford’s catalogue of the Nemi material to give the Nottingham curator how long I might wish for that visit later this year.

I was struck by the large numbers of RRC 38/7 and the pretty remarkable number of RRC 38/3 as well.

The former Mercury-Prow struck piece seems to average in the 6-4 grams range, and this small Roma-Prow seems to fall in the 3-1.5 grams range. (I’m eyeballing not actually running the numbers here!)

What really gets me is that this is the only so called quartuncia in the whole series. There are more of this type of semuncia to follow that look very similar and also are without a denomination mark but previous semuncia absolutely had a denomination mark and very late semuncia also had denomination marks (all semuncia types in CRRO).

How would anyone have known that these two coins were these denominations? Clearly they were accepted and readily used and small, light coins are certainly convenient, but after distribution as pay (if that is how they entered circulation), how did they come to be accepted and spendable at a specific monetary rate. How different at all are these from earlier struck bronze (issued at the same time as cast!), which Crawford called litra or double litra, such as RRC 13/2, RRC 16, and RRC 17 and more (all these types of issues in CRRO). These three show up in the Nemi lists. Why aren’t we calling 38/3 a litra and 38/7 a double litra?!

Grueber BMCRR p.26n.1 says D’Ailly (p. 115) is the first to recognize this denomination and connected it to the semi-libral standard.

Today, as I’m able:

Book manuscript PR review

article PR review

send emails RE Nottingham

Schaefer

RE April event

that’s more than enough…

I’ve just finished up here at Rutgers and am waiting to discuss my early findings with a colleague, but I have some extra time before he arrives.

I’ve wrapped my head around zinc levels to be satisfied that in a few cases I can reject specimens from my analyses when levels are far too high. The other big interference is Light Elements, basically oxidation. All those readings go out the window too, even when I think the specimen is likely genuine. I do leave them in for other fabric analyses. But then what about other unexpected elements that keep coming up. The list of modern patina chemicals given below is quoted directly from the Newman Portal.

This type of ‘enhancement’ might explain to some degree some of the odd stuff I’m seeing, including perhaps some of the light elements (N, H, O etc…)

A big one that has been turning up is SULFUR. Obviously it could be naturally occurring from the conditions of deposition. Italy has TONS of the stuff. Campi Flegrei ?! This sort of interference from natural incrustation is my first assumption when I turn loads of CALCIUM as well.

—- I GOT MY FUNDING TO GO VISIT THE NEMI MATERIAL—

[That news came in as I was typing: had to share in real time.]

The other thing that shows up is CHLORIDE which is associated with bronze disease. On some specimens I suspect it is in fact bronze disease, but I wonder if in some cases it might be ‘enhancement’. Wouldn’t the use of this in patina creation be a bad idea? Couldn’t it lead to bronze disease and irreversible damage?

The other real insight was the use of BARIUM in the creation of patinas, I’d gotten some really surprisingly high barium readings and really was flummoxed by that until reviewing this list.

I also found the use of IRON in these patina’s a little surprising. Iron does show up in my readings but as it showed up in high levels in ramo secco (Burnett, Craddock, Meeks 1986) I thought it was most likely naturally occurring. I wonder if I could spot the associated nitrate salts.

The final element that has shown up that I don’t know if it is natural or not and isn’t in this list is SILICON. In the modern world there are manufactured silicon bronze alloys but I highly doubt anyone has used these to fake coins.

Please don’t take anything in this post as ‘fact’. I’m still thinking through the material and trying to make up my mind what to think.

[begin quotation]

Patina chemicals. The following chemicals are some of the more frequently used in patina finishes:

Ammoniumcarbonate (NH4)2 CO3.H2O. A mixture of ammonium bicarbonate and carbonate. Used for a bronze patina of bluish-green color. Also called “hartshorn.”

Ammoniumchloride (NH4Cl) A patina solution for coloring bronze a verde antique green. Also called “sal ammoniac.”

Ammoniumsulfide (NH4)2SO4 An excellent darkening agent for bronze and silver in highlighting during a finishing operation. The objects to be darkened are immersed in this chemical for less than ten seconds – the sulfide is the source of sulfur as the darkening agent. Also called “sulfate of ammonia” and “sulphuret of ammonia.”

Barium sulfide (BaSO4) Used as a coloring agent for bronze medals for a light brown color, called “Old English.”

Copperchloride (CuCl2) A patina coloring chemical producing yellowish-green color on bronze. Also called “cupric chloride.”

Coppernitrate (CuNO3) Used for dark blue and green patina coloring on bronze. Also called “cupric nitrate”

Coppersulfate (CuSO4) Colors bronze green. It is the green corrosion on copper items in an atmosphere exposed to sulphur and moisture over long time. The composition of incrusted patina.

Ferricnitrate (Fe(NO3)2) For use only by very experienced finishers; colors a dark chocolate color. Care must be used, however, as some of the nitrate salts can spot the surface.

Liversulfide (K2S) Used for a bronze patina on statues and medals; it produces a color from redbrown to dark brown. Also called “liver of sulfur,”“potassium sulfide,” “sulfurated potash.”

Liquidsulfur. (S) Quickly turns bronze and silver a dull black.

Oiloflavender. A bronze patina of pale ashen green color, formed by adding yellow pigments to oil of lavender.

Potassiumnitrate (KNO3) is a patina solution for turning bronze a dark red color. It is most used for tempering tool steel (heat treating dies) and for chemical analysis. It is also called “saltpeter.”

Potassiumpermanganate (KMnO4)

[end quotation]