In Spring 1999 in my first grad seminar with Fergus Millar and Robert Parker, I gave a presentation inspired by my future (at that time unknown to me scholar).

Clarke, Katherine. “In Search of the Author of Strabo’s Geography.” The Journal of Roman Studies 87 (1997): 92–110. https://doi.org/10.2307/301371.

I read this and thought, “this! exactly exactly this!” what I want to do with my PhD dissertation and I wanted to focus on Polybius. Within in the next 12 months I realized I couldn’t survive a thesis on Polybius, not because of the work, but because I needed to move on from my then-supervisor and his sexualized approach to mentorship (Thanks Fergus!). With the help of Michael Crawford and a conversation on the train platform of Benevento, I decided to throw myself into the Post-Polybian world. A world I have always seen through the lens of my first love of Polybius.

Today, I’m seeing if I can’t bang out a short chapter on Dionysius (another one) for a conference volume. I’m trying to capture something of how I read Dionysius by referring to past scholarship my own forthcoming work. I realized I want to cite this very first seminar presentation. Of course it was never published and it is more didactic, but wow, I’m pleased with my young mind. I’d have liked me as a student. That methods seminar also had Esther Eidinow and Luke Pitcher and Peter Liddel and others I’m sure others I should remember.

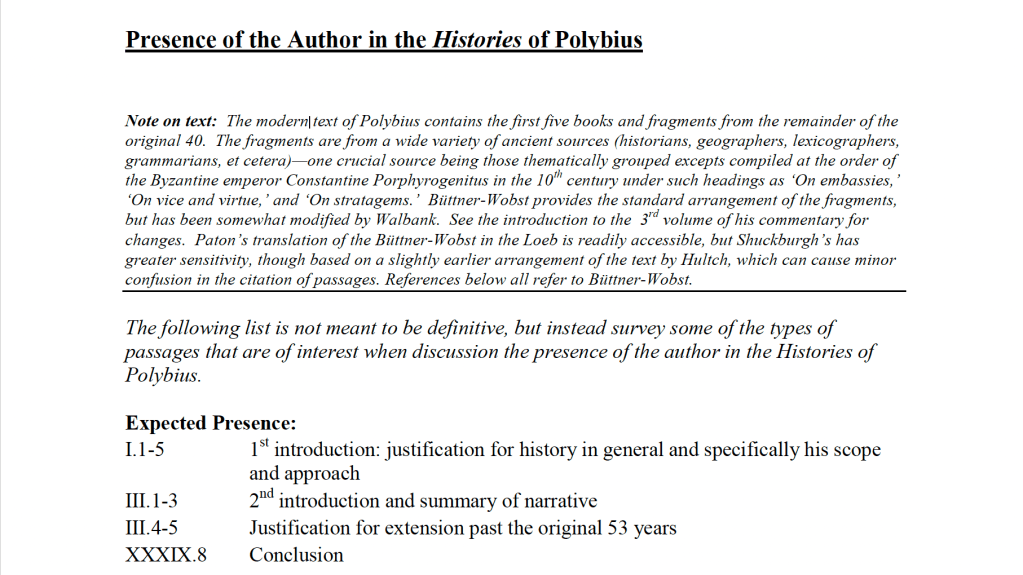

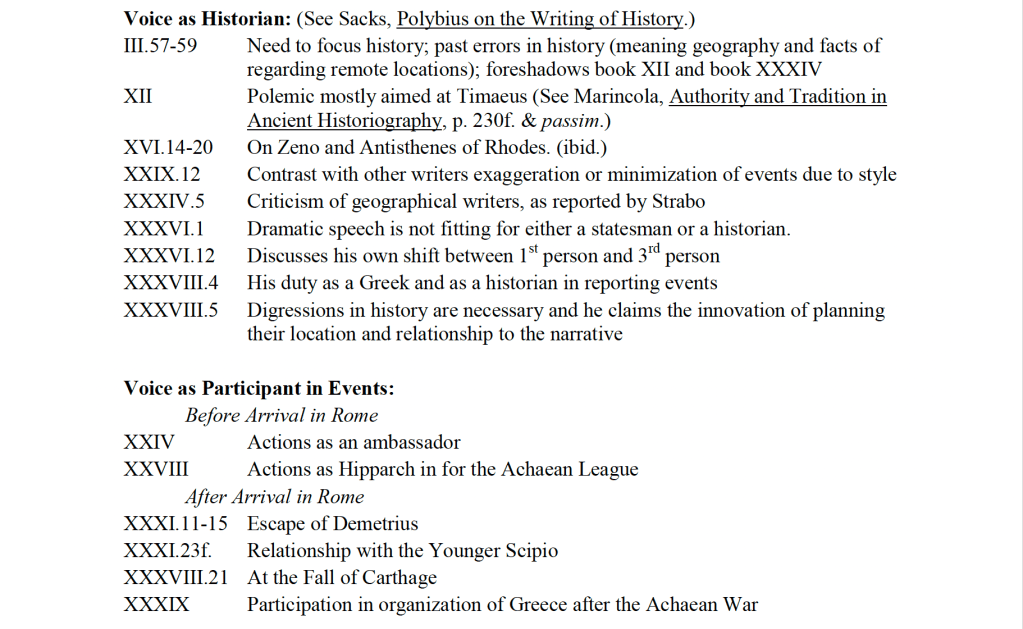

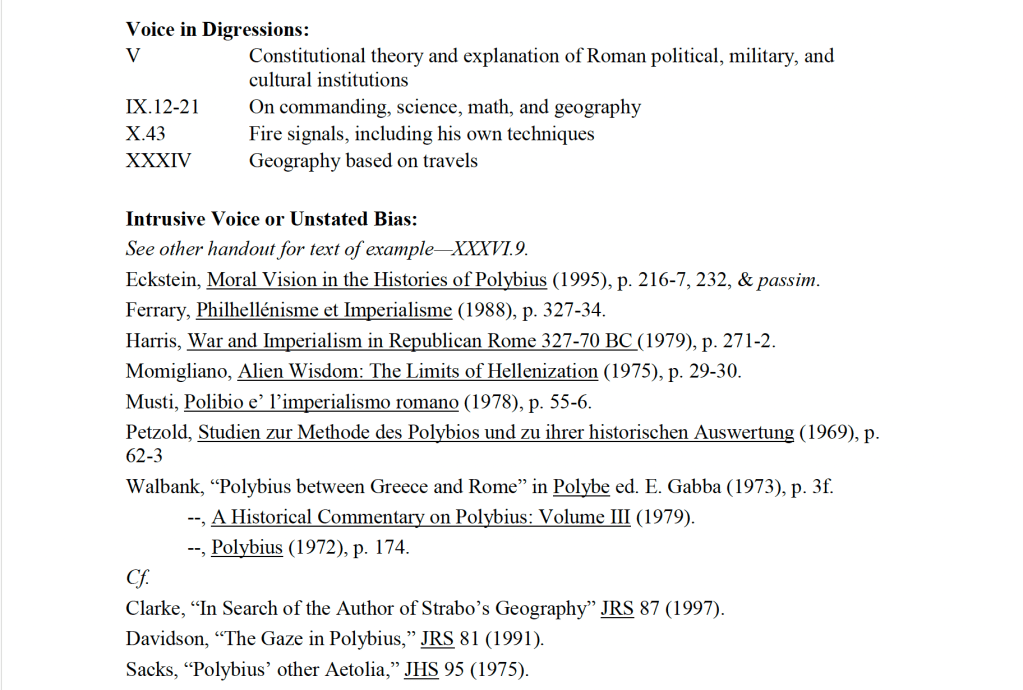

Handout

Speaking Notes

Not covering everything on the handout

Basic Bio:

- Born circa 205

- Megalopolis in Arcadia, part of the Achaean league

- Father eminent statesman; raised with the expectation of reach high political office and influence

- We’ll come to some of the details of his political and military career later.

- In the aftermath of the 3rd Macedonian war, as a result of political rivalry with in Achaea and his family’s cool attitudes towards Rome’s intervention in the East, Polybius along with 1000 of other Achaeans was deported to Rome for ‘questioning’ and detained without resolution for 16 years.

- Catalyst for writing career? Even suggested that the part of the history covering the 3rd Macedonian war began as his own detailed notes in preparation for examination in Rome on his own ‘anti-Roman’ actions.

- Relationship with Scipios, come to later.

- Travel

- Return to Greece after the Achaean War and carried out the settlement imposed by the 10 Roman commissioners.

Thought it would be most interesting to skim through the obvious examples of self-expression, touching on just few points, and then focus on one famous example of the ambiguity and sophistication Polybius uses to express own opinions and motivations.

Plan of Histories was originally 30 books with the first 2 books serving as pre-history/extended introduction covering 264 to 220. The history proper covers book 3 through 29 down to 167. The last 10 books, well excluding book 40 which though wholly lost served as an index, followed events down to 145. Walbank has won acceptance for the idea that Polybius further sub-divided the last 10 books into those covering the period of un-contested Roman rule and those following his geographical excursus in 34, 150 following which he alludes to in book 3 as the point of turmoil from which he has to write as if starting over.

As you can see he has two separate introductions—most notable because he abandons the tradition of introducing himself as the author of the text. In fact he never does introduce himself though his self references seem to assume the audience is aware of his name and dual role. The closest he comes in the actual introductions is in III.5 where he points out that one of the reasons for ‘starting a fresh’ for the period of turmoil is his own personal involvement in those events. But to be honest, it is hard to see any drastic change in style in these last 4 books—this could of course be because of their fragmentary nature.

His other unusual feature is his variation between the narrative voice of the 1st person singular and the 1st person plural as well as discussing himself as a participant in events in the 3rd person. Clarke, in her Strabo article, suggests that the 1st person plural could be being used in an analogous way to the modern scientific passive voice in that it lends credibility by appearing unbiased, but it could also be seen as a way of identifying with the audience, which Polybius generally identifies as Greeks, but does express awareness of possible Roman readers. The variation between 1st and 3rd person is less confusing, Polybius tells us he does this for reasons of modesty, XXXVI.12, but any reader would conclude that the shift allows one to keep separate Polybius, the political figure, and Polybius, the historian. He also expresses concern over this duality of roles. This is seen in both XXXVI.1 and XXXVIII.4, cited on your handout under Voice as a Historian. And while it causes him to some personal conflict he also is a firm believer that only some one who participates in a type of activity can write about it (Book 12), as well as the need to limit the range of a history to that which reliable sources can be obtained, i.e. contemporary history. so it would seem that he thought his dual role should neither be uncommon among writers, nor an inconvenience.

It is however his dual nature both in the sense of being a write and a historian as well as being a Greek who associated and advised the Roman elite which causes modern historians so much concern of his own bias. Walbank, to whom most concede, suggests that Polybius shows pro-Achaean opinions from the beginning the end of the histories, but that in the last 10 books he also shows sympathy towards the Romans. It is also assumed that as an Achaean Polybius is anti-Aetolian, the traditional enemies of his league, and he does use seriously derogatory language through out the first part of the histories, but Sacks has shown that from the War with Antiochus onwards he sympathizes with this age old enemies. It almost seems as if upon assuming his identity in exile he changes from being an Achaean to being a ‘Greek.’ This can also be seen in his sympathy towards the Greeks for the Roman conquest of 146, but out rightly blames his own countrymen for bringing it upon them.

But more recently modern historians have set aside the simplistic question of where is his bias to looking for conscious techniques or trends in Polybius’ writing. Notably Eckstein who attempted to show an overall moralizing in the histories vs. a Machiavellian or pragmatic outlook. While, he is largely unconvincing on the moral basis for his observations he does extensively outline those places in the narrative where Polybius as the narrator interjects judgements or comparisons. There is much room for further discussion on these points of where Polybius’ opinions along side the chronological history. Davidson is also concerned with Polybius form of self expression; he used a modified definition of focalization to describe what he termed the ‘Gaze’ in the histories, namely allowing the reader to see events and characters from various vantage points.

Oddly enough in his discussion he does not touch upon possibly the most famous and controversial point at which Polybius uses the views of others within to supplement his record of events. This is XXXVI.9 which you have on your handout.

While you read count the number of opinions which Polybius differentiates

-break to read it-

There are normally thought to be 4 opinions, but a case may be made for a fifth. A variety of scholars have wanted do approach this text differently. One school of though assumes that one of the opinions is Polybius’

This include Walbank who supports the last one, based on its length and emphatic placement, and his inability to believe Polybius would be critical of an act, i.e. the destruction of carthage that he participated in.

Musti and Petzold disagree. And see support for the two middle negative opinions in the rest of the histories, namely Book X.36.2 where Polybius says same acts must be done to maintain and empire as to keep it and Book V.11.5 where Philip V is condemned for wonton distruction of cities he conquers. They also bring in ‘Polybian’ passage from Diodorus, but their origin is doubtful.

Others are less limiting in their view of the possibilities:

Eckstein briefly looks at it to try to find Polybius’ views on Carthage not Rome.

Momigliano suggests that while the majority of the history is intended to explain Rome to the Greeks this passage is part of a latter trend to explain Greeks to Rome. Fanciful?

Harris suggests that if all the opinions can be supported from the histories may be they all reflect part of Polybius’ thinking.

Ferrary does not commit to any one or all being owned by Polybius, but does fall up connections between the various opinions and other passages in the Histories.

Though, Davidson did not discuss this passage his technique of focusing on narration versus bias might lend him to agree with a view that the passage is a way to balance the Carthaginian perspective and the Roman perspective of the conflict and maybe even illustrate that with the development of its empire Rome has brought more participants into the discussion.

Any thoughts on this passage….

or any questions from parts of the handout I did not concentration….

Check:

The 38.4 I was meaning is, I think, 38.6 in Shuckburgh (Hultsch’s text). Along with that see 39.3 (39.14 in S., I think) and 39.5 (39.16 in S.) for Pol. being historically present (i.e. actually there at the time and doing). Other historiographical presences you’ve spotted, but the historical presences are interesting, too. A mix of the two kinds of presence in 3.22.4 and surely in 3.29.1 (n.b. the present tenses: he was there and listening); 31.25.5a (31.24.4 in S.) looks like another example of Pol. there and listening (I think Fergus is fond of that one; may be a ref. to it in his piece in JRS 1984, 1-19.). I’m inclined to believe that Pol. is unique in this way.