More pre writing.

After this he went to the city of Crenides, and having increased its size with a large number of inhabitants, changed its name to Philippi, giving it his own name, and then, turning to the gold mines in its territory, which were very scanty and insignificant, he increased their output so much by his improvements that they could bring him a revenue of more than a thousand talents. And because from these mines he had soon amassed a fortune, with the abundance of money he raised the Macedonian kingdom higher and higher to a greatly superior position, for with the gold coins which he struck, which came to be known from his name as Philippeioi, he organized a large force of mercenaries, and by using these coins for bribes induced many Greeks to become betrayers of their native lands.

Diodorus 16.8

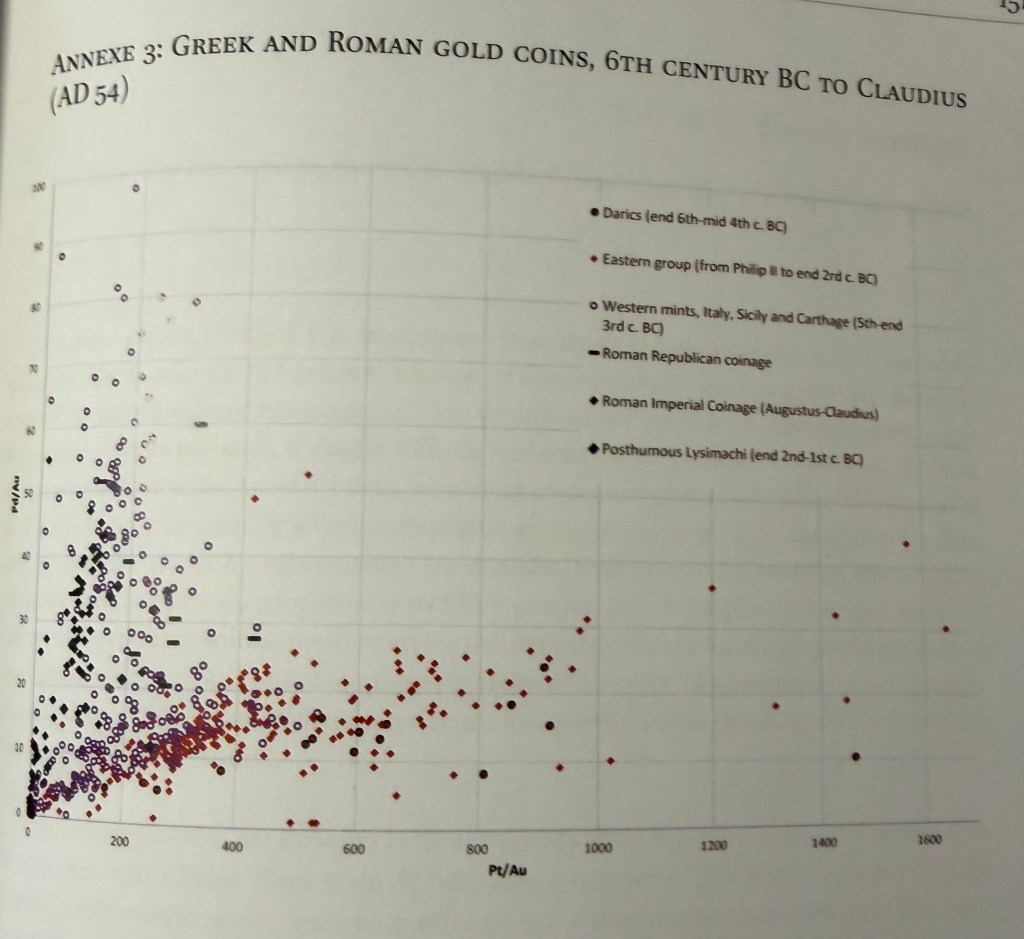

I’m on to Duyrat et al. in AVREVS. It’s nice when our data matches our literary testimony. Here we have some further conversation use of die studies for quantification similar to the previous chapter but they quickly move on to metallurgical analyses. These seem to confirm that Philip’s initial striking of gold is very low in Palladium and Platinum consistent with recently mined ore, such as Diodorus point out. The analyses also show far higher and variable levels of Palladium and Platinum for both Darics and Alexanders struck in Asia Minor. The authors quote Herodotus and Strabo to suggest that the higher variable levels of these trace elements is reflective of repeated melting and mixing of the metals.

This was the tribute which came in to Dareios from Asia and from a small part of Libya: but as time went on, other tribute came in also from the islands and from those who dwell in Europe as far as Thessaly. This tribute the king stores up in his treasury in the following manner: — he melts it down and pours it into jars of earthenware, and when he has filled the jars he takes off the earthenware jar from the metal; and when he wants money he cuts off so much as he needs on each occasion.

Herodotus 3.96

…also the following, mentioned by Polycritus, is one of their customs. He says that in Susa each one of the kings built for himself on the acropolis a separate habitation, treasure-houses, and storage places for what tributes they each exacted, as memorials of his administration; and that they exacted silver from the people on the seaboard, and from the people in the interior such things as each country produced, so that they also received dyes, drugs, hair, or wool, or something else of the kind, and likewise cattle; and that the king who arranged the separate tributes was Dareius, called the Long-armed, and the most handsome of men, except for the length of his arms, for they reached even to his knees; and that most of the gold and silver is used in articles of equipment, but not much in money; and that they consider those metals as better adapted for presents and for depositing in storehouses; and that so much coined money as suffices their needs is enough; and that they coin only what money is commensurate with their expenditures.

Strabo 15.3.21

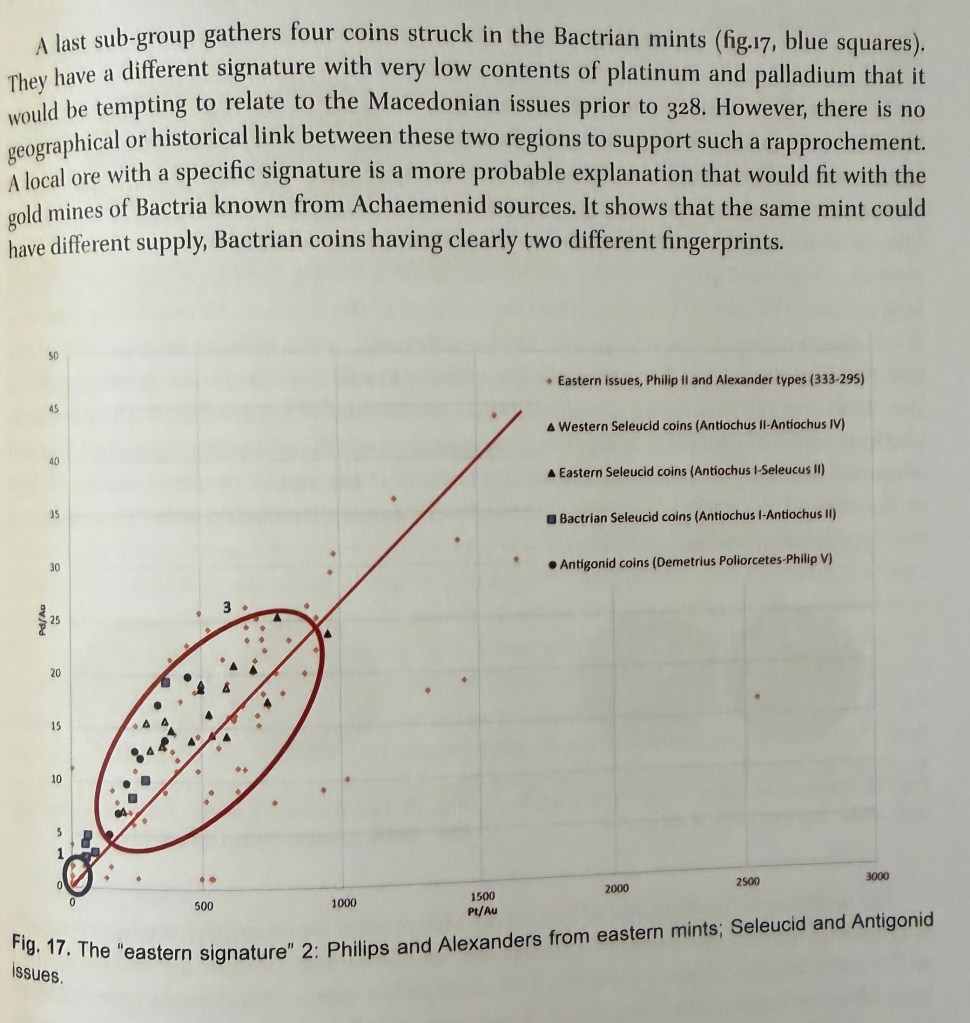

Unsurprisingly most of the Seleucid gold shows the same type of mixing, the exception being the Bactrian mint which not only strikes recycled metal but also seems to access local mines for fresh ore and to coin that as well.

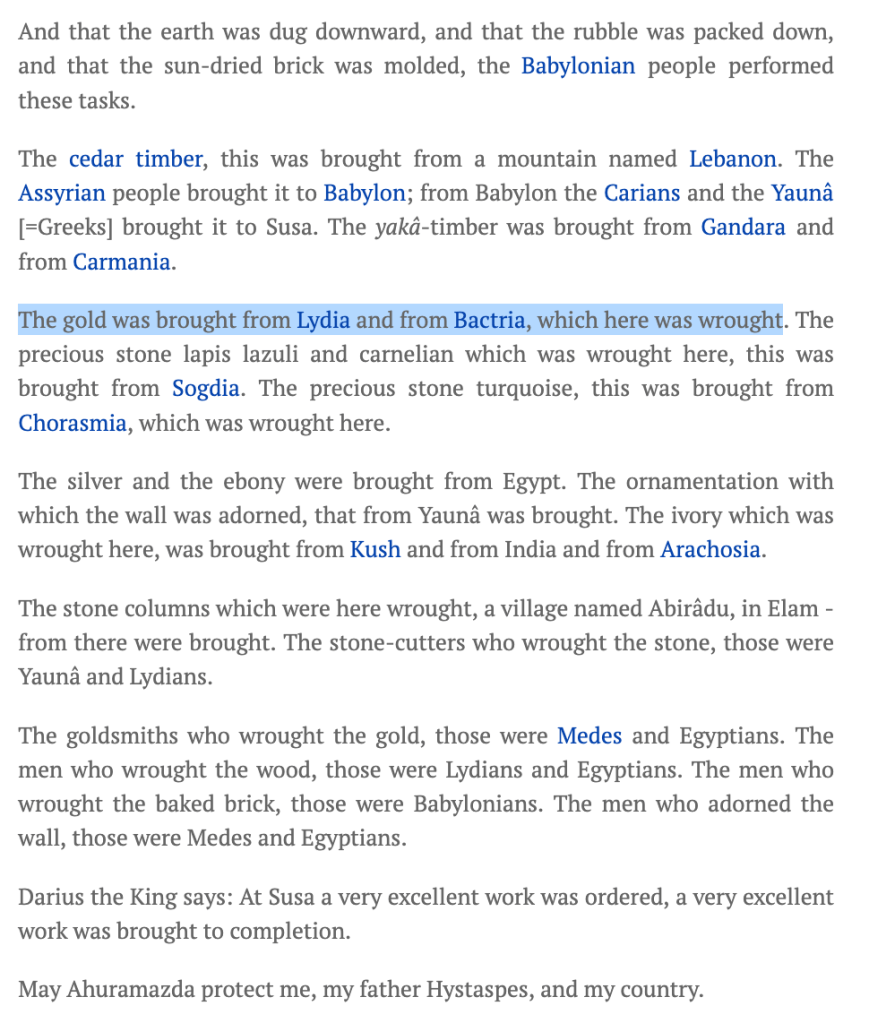

Again as the authors point out this corroborates epigraphic testimony that Bactria supplied the Achaemenids with gold.

I would note that Bactria is not marked out as a particular source of gold in Herodotus’ accounts of tribute paid to Darius, he reserves this role for “India” (cf. 3.92 and 3.94). This fits well with Herodotus’ world view where gold comes from the far east and is associated with ‘gold digging ants’ (3.102-105). He says the Indians there live much like the Bactrians. (cf. the gold guarding griffins at 3.114)

The authors note of the Ptolemies: “Although they developed a closed monetary system and exploited resources in gold in the eastern desert, potentially with different characteristics, no new signature can be detected.” p. 137

In short Ptolemaic gold looks much like Seleucid gold (excepting a bit from Bactria) which looks much like Alexander’s gold and that of the Achaemenids.

When turning to the Western Mediterranean they note that a wide range of alloys were struck. In the east gold coins are nearly pure gold, where as alloys in the west may vary from over 96.5% gold down to 20.4%, most notably at Syracuse and Carthage. But for me the best was saved for last. Look how much the Roman republic coins fit right in with other western gold.