In an article published in 2007, I attempted to explore multiple perspectives to define the coined share of precious metals in the Hellenistic world. Somewhat to my surprise, it repeatedly emerged that this share was a minority, if not small, probably less than 20%. In a paper intended to follow up on this, presented shortly after in 2009, I tried to estimate the importance of this Hellenistic goldwork, a task far more arduous than estimating the amount of coined metal. I certainly did not succeed in a field dominated by art history, where quantification remains, even today, in limbo. But it is clear that goldwork must be integrated into our reflections.

De Callataÿ in AVREVS p. 93

The 2007 article is listed by google scholar as 2006.

François De Callatay, 2006. “Réflexions quantitatives sur l’or et l’argent non monnayés à l’époque hellénistique (pompes, triomphes, réquisitions, fortunes des temples, orfèvrerie et masses métalliques disponibles),” ULB Institutional Repository 2013/114583, ULB — Universite Libre de Bruxelles.

The 2009 essay was published in the following volume appearing in 2017:

Liámpī, Katerínī., Dimitris Plantzos, and Κλεοπάτρα Παπαευαγγέλου, eds. 2017. Νόμισμα / Κόσμημα : Χρήσεις, Διαδράσεις, Συμβολισμοί, Από Την Αρχαιότητα Έως Σήμερα : Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Ίος, 26-28 Ιουνίου 2009. Αθηνα: Εταιρεία Μελέτης Νομισματικής και Οικονομικής Ιστορίας. [Academia.edu link to De Callataÿ chapter]

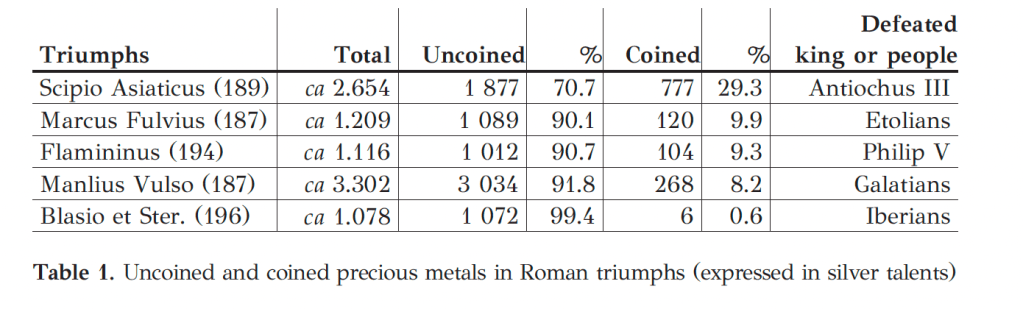

This table is handy and fascinating!

My first thought is how much of the uncoined then in turn became coined by the Romans themselves?! And then how much of the uncoined metal was previously struck as coins and then recycled to create the very objects being carried in procession? Finally does this preference to display uncoined metal reflect the tastes of the triumphators to create spectacle. Gold and silver objects may be easier and more impressive than coins when carried in parade. How do you even display mountains of coins in such a moving spectacle?!?!

The display of coins is particularly presents a challenge. Think of the iconography of liberalitas under the empire where the money shovel becomes the key symbol not piles of coins themselves.

Heaps of coins are impressive yes but they tend to slide all over the place once you get beyond a relatively small amount. Here I cannot help but recall Frank Holt on the coin as meme (in the Dawkins sense and less in the internet phenomenon) — a great book, consider buying if you’ve not yet.

I’d also point out that not all the coin acquired by the commander in the war needs to have been carried in the triumph itself. Commanders gave coin largess to troops during the campaigns themselves and could acquire coin and use it for purchases on campaign reserving objects for purposes of the triumphal spectacle, conspicuous dedications in sacred spaces at Rome AND abroad, as well as alliance building through ‘repatriating’ materials to presumed ‘rightful’ owners Cf. Scipio at Carthage calling Sicilian embassies to reclaim lost artifacts c. 146BCE.

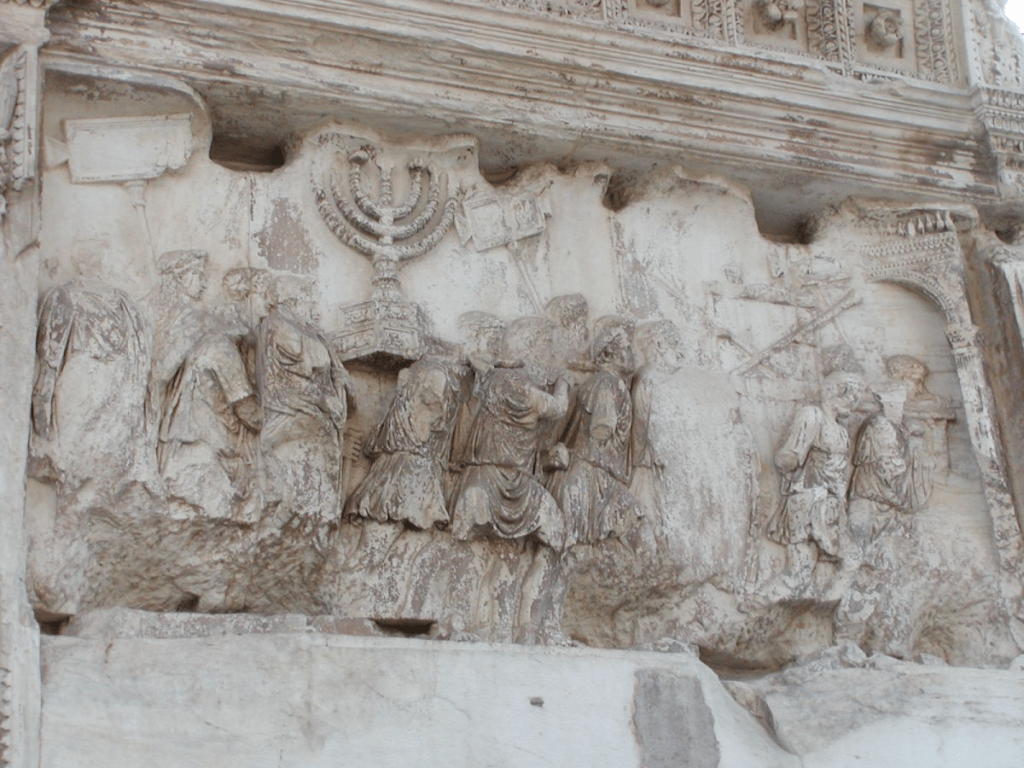

None of this is to undermine De Callataÿ’s larger point that at any one time a great deal of precious metal, esp. gold would be in uncoined form. We know all this material was heavily recycled and repurposed throughout antiquity. we might even recall of how the gold hieroglyph derives from a pictogram of a necklace! It seems highly likely to me that gold as primarily a crisis coinage was more often stored as object rather than as coin. Look again at the above fresco the precious metal pile of coins has eight gold pieces in a vast mountain of silver, it visually communicates the relative scarcity of gold coin even amongst the well-moneyed, as well as how bronze coin is segregated from precious metals, but what gold coin there is travels with the silver coin.

Generally speaking I find De Callataÿ’s attempts to treat quantify the volume of surviving gold jewellery a worth-while endeavor and what I’d like to do is think more about this methodology in relationship to inscriptions on silver objects that record their weights, a topic on which Alice Sharpless is the expert (earlier related blog post) and from there the bronze statues with weight inscriptions at San Casciano de Bagni (see my notes from last AIA-SCS here).

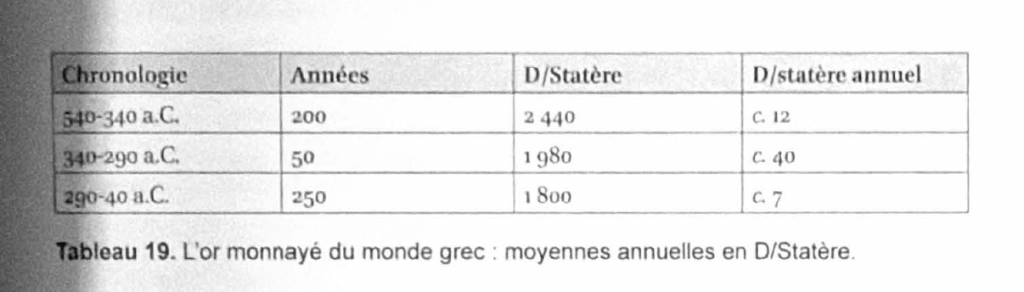

Circling back to the AVREVS volume, De Callataÿ relies on average weight standards, observed numbers of coins, and observed numbers of dies to across ALL gold issues (including Roman republican!) distill down an estimate of how much gold was struck in various periods:

We see, therefore, that the gold of the age of Alexander [340-290 BCE] does indeed represent the largest gold minting ever produced in the Greek world, but that this preeminence is perhaps less pronounced than has long been thought. First, because the total number of Alexanders has been revised downwards (1,000 staters instead of 1,200); second, because there are earlier, large-scale mintings such as the Cyzicean issues, the Darics, and the Croeseids, which also amount to hundreds of staters; finally, the examination conducted here further indicates that it would be a mistake to consider only the Alexanders, Philips, and Lysimachus, given the scale of production down to the end of the 1st century.

De Callataÿ in AVREVS p. 109

He goes on to discuss the fragility of our evidence because of differing survival rates and also highly variable reporting of finds. This is a theme he is cognizant throughout the chapters. I think this picture may change how we read Plautus as well…. See last post. Perhaps indeed make De Callataÿ sympathetic to at least some of my arguments about gold and the Romans. …

My take aways from this is how critical die studies are for this type of quantification and also how much periodization matters and how we need to look across geographic boundaries.