I’m still pre-writing and still working my way through AVREVS with an eye to fuzzy boundaries of periodization, culture groups, and by extension disciplinarity in numismatics. For full citations and more on this project see previous post.

De Callataÿ’s chapter (pp. 91-114) begins by summarizing his 2015 work and re committing to its primary thesis. I thought perhaps best then to remind myself of that work before looking at the newer work where he links his textual readings to material data.

It is a rare thing for me to disagree with a scholar I admire so much. It worried me enough that I left the library yesterday in a bit of funk, committed to sleeping on the topic. And thus am revising my original notes before posting. The truth is De Callataÿ is an insightful reader of Roman comedy with a keen eye to the economic implications of the texts. I don’t disagree with the vast majority of his 2015 article and really after page 31 it brilliantly captures the full breadth of economic and monetary history we can extract from the corpus of these Latin plays. So why my funk. I don’t even disagree with the premise that the plays are good evidence for the Hellenistic period, it is only that I believe that Rome is very much at the time of the writing of the plays a Hellenistic state and that the plays reflect a shared reality. I am also very persuade by Amy Richlin’s work on the creation and context of these plays and performance, a world of the enslaved, and thus of individuals involuntarily culturally relocated from one setting to another.

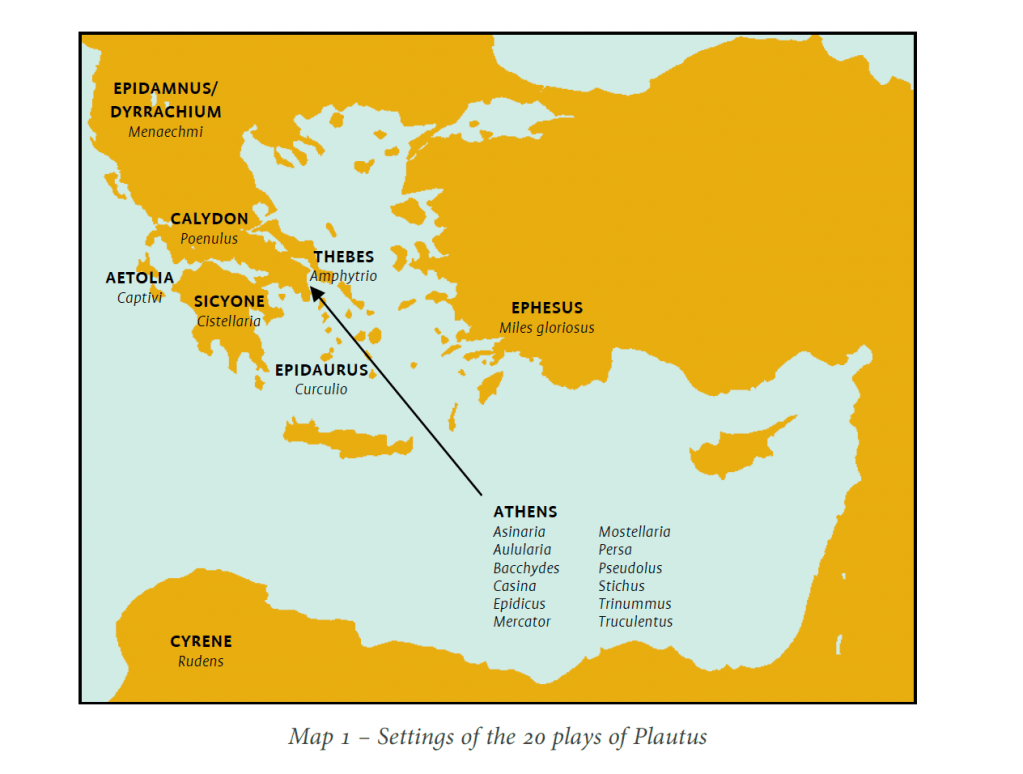

Thus in what follows are my reading notes on why I think De Callataÿ goes too far to try to create a strict dichotomy between the realities of Rome and the realities of the Hellenistic World in the time of Plautus and Terence, post 1st Punic War down to the decade just following the 2nd Macedonian War. Read Rome as economically and monetarily as fully Hellenistic in this period. This means that plays adapted from themes popular in Greek drama in an earlier Hellenistic period are equally relevant to a Roman audience.

—

I wonder if De Callataÿ might temper his views of the (lack of) romanitas in the plays.

Richlin, Amy. Slave theater in the Roman Republic: Plautus and popular comedy. Cambridge University Press, 2017. (BMCR review)

I also wonder if I am allowed a middle ground, a via media, by which I assert that the Romans are part of the Hellenistic world and that in particular the enslaved and/or formerly enslaved who developed and performed these theatrical productions were products of the Hellenistic Mediterranean with its incredible (and disturbing) mass movements of humans through enslavement, fueled by the ambitions of competing empires.

The Romans engaged in overseas trade and investments

Key to De Callataÿ’s argument in 2015 is that at the time of Plautus and Terence the Romans were not regularly engaged in overseas private travel for business/investment and thus the interconnected world of commerce so readily seen in the plays must be wholly Greek, and set in the world of the 4th and early 3rd centuries (cf. p. 22). Plautus is usually said to have died 184 BCE and Terence 159 BCE. Would their audiences recognize overseas investments in land and trade as applicable to the Romans? I think so. The senatorial class is so obsessed with presenting itself as agrarian that our literary sources tend to minimize everything else (e.g. Cato, On Agriculture), but we nevertheless can see plenty of overseas investments. Romans and their allies were keen to acquire land in Sicily following the 1st Punic War and after the 2nd Punic War we see extensive mining operations in Spain. We know of the extensive trade in vernice nera with petites estampilles with Iberia esp. the region of Catalonia, a type of pottery deeply characteristic of 3rd century Italy. In 166 BCE the Romans converted Delos into a free port. The advantage of doing so to Italian traders is well demonstrated by later epigraphic influence but the impetus to do so was likely predicated on prior Italian trade interests in the Eastern Mediterranean. The setting is Greek but the behaviors and inter-connectivity are Hellenistic, one’s the Romans and their Italian neighbors readily engaged in.

I want to think of more examples here but I also want to move forward, so for now one corroborating citation:

ROTH, ROMAN. “TRADING IDENTITIES? REGIONALISM AND COMMERCE IN MID-REPUBLICAN ITALY (THIRD TO EARLY SECOND CENTURY BC).” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, no. 120 (2013): 93–111. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44216740.

Roman warfare enriched soldiers

The social structures of the plays are discussed as non-Roman on p. 23 following. I think Richlin does a thorough enough job on the “pimp” and “courtesan” (enslavers and enslaved) that I can just nod her direction. But I must disagree with this assertion that seems to believe that the Romans were as sober and abstemious as they tell us they were.

My knee-jerk reaction is that we know that the distribution of spoils was an expectation of Roman soldiers from a very earlier period and even if all spoils were ostensibly the property of the general for him to distribute as he saw fit, we also have anecdotal reports of the greed of individual soldiers in battle and the plundering of cities.

Marian Helm, Saskia T. Roselaar, Spoils in the Roman Republic: boon and bane. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2023. Pp. 467. ISBN 9783515133692. [BMCR review]

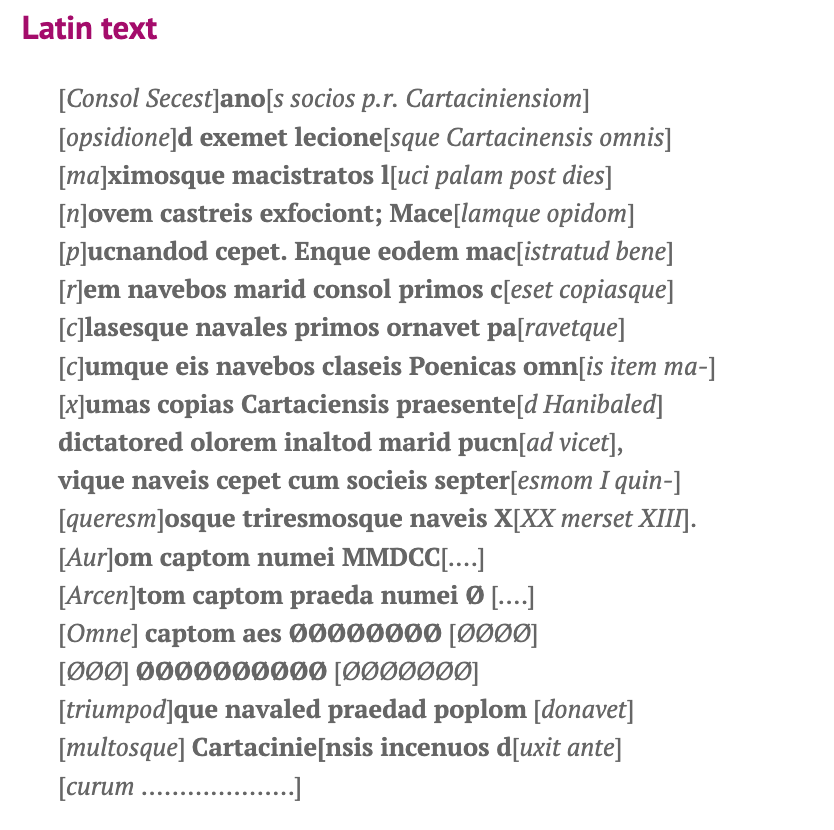

The volume of spoils of the wars witnessed by Plautus and Terence and their audiences were massive and seemingly ever increasing. As early as 260 BCE (before Plautus’s presumed date of birth) the spoils of war were being distributed not only to the soldiers but even to the whole citizen body.

Text and translation from Livius. I however hold that inscription is based on a 3rd century BCE original and is not an Augustan fantasy, only a restoration. I discuss it building on the views of Eric Kondratieff first in a 2014 blog post and then more extensively in my 2021 PR journal article.

The expectation of broad scale riches for the soldier was well in place by 167 BCE

The military tribunes had received instructions as to what they were to do. All the silver and gold had been collected together in the morning, and at ten o’clock the signal was given to the soldiers to sack the cities. So great was the amount of booty secured that 400 denarii were distributed to each cavalryman and 200 to each foot soldier, and 150,000 human beings were carried off. Then the walls of the plundered cities, some seventy in number, were destroyed, the booty sold and the proceeds furnished the above-mentioned sum for the troops. Paulus went down to the seaport of Oricum, but his soldiers were far from satisfied; they resented being excluded from all share in the plunder of the palace, as though they had not taken any part in the Macedonian war.

Livy 45.34

Valerius Antias states that all the gold and silver coinage carried in the procession amounted to 120,000,000 sesterces, but from his own account of the number of wagons and the weight carried in each, the amount must undoubtedly have exceeded this. It is also asserted that a second sum equal to this had been either expended in the war or dispersed by the king during his flight to Samothrace, and this was all the more surprising, since all that money had been accumulated during the thirty years from the close of the war with Philip either as profits from the mines or from other sources of revenue, so that while Philip was very short of money, Perseus was able to commence his war with Rome with an overflowing exchequer. Last of all came Paulus himself, majestic alike in the dignity of his personal presence and the added dignity of years. Following his chariot were many distinguished men, amongst them his two sons, Quintus Maximus and Publius Nasica. Then came the cavalry, troop after troop, and the legionaries, cohort after cohort. The legionaries were given 100 denarii each, the centurions twice as much, and the cavalry three times that amount. It is believed that he would have doubled these grants had they not tried to deprive him of the honour, or even if they had been grateful for the actual amount which he did give them.

Livy 45.40

Did these amounts even one that was considered far too low by the ordinary soldier represent a life changing amount of money? I think yes. Stipendium is typically presumed to be a denarius ever three days for infantry, with grain and other matters deducted. 100 denarii is perhaps approximately what a soldier could earn in a whole year of fighting. 300 denarii (the Epirus donative and the donative after the triumph combined) is likely a generous 3 years livelihood. Any ordinary person handed 3 times they’re typical annual earning power is going to feel and perhaps act as having a very significant windfall. Yet these soldiers felt it was disappointing. Just over 3 decades earlier Scipio had given out only 40 asses per soldier but expectations were shifting fast, esp. in light of the influx of eastern wealth. Besides reports of cash pay outs Roman soldiers had long been rewarded in kind, especially with land or the use of land. If the speculation that Miles Gloriosus might have been first staged in 206 BCE is correct, the stock character of the braggart soldier enriched by War could certainly have been relatable to Roman audiences and may have even engendered hopes of a return to economic prosperity after the end of the Hannibalic War.

Taylor, Michael J. Soldiers and Silver: Mobilizing Resources in the Age of Roman Conquest. University of Texas Press, 2020. [JRS review]

Charlotte Van Regenmortel, Soldiers, wages, and the Hellenistic economies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024. Pp. 276. ISBN 9781009408981. [BMCR review]

Nummus means “Coin”. Romans are well aware of Greek Denominations.

A tetradrachm is unfamiliar to the Romans? This seems implausible. AND, to his credit, De Callataÿ pretty much retracts this claim later in the same article (p.27-28).

The didrachm was preferred in peninsular Italy for striking and circulation and thus this is the first silver denomination struck by the Romans themselves, but that other denominations were preferred elsewhere was widely known:

There were carried in the procession 230 of the enemy’s standards, 3000 pounds of uncoined silver, 113,000 Attic tetrachmi, 249,000 cistophori, and numerous heavy vases of embossed silver, as well as the silver household furniture and magnificent apparel which had belonged to the king. There were also 45 golden crowns presented by various allied cities, and a mass of spoils of every description; 36 prisoners of high rank, the generals of Antiochus and the Aetolians, were also led in the conqueror’s train.

Livy 37.46 (190 BCE)

The key Latin: signati tetrachmum Atticum centum decem, tria milia, cistophori ducenta undequinquaginta

Already in the triumph of Flamininus do we have specifics about the denominations of coins being carried in triumph (194 BCE):

On the second day all the gold and silver, coined and uncoined, were borne in the procession. There were 18,000 pounds of uncoined and unwrought silver and 270 of silver plate, including vessels of every description, most of them embossed and some exquisitely artistic. There were also some made of bronze. In addition to these there were ten silver shields. Of the silver coinage 84,000 were Attic pieces, known as tetrachma, each nearly equal in weight to four denarii. The gold weighed 3714 pounds, including one shield made entirely of gold, and there were 14,514 coins from Philip’s mint. In the third day’s procession were carried 114 golden coronets, the gifts of various cities

Livy 34.52

Enslavement is a means of transporting knowledge. Every time anyone is forcibly moved from one culture to another they bring cultural knowledge. Richlin argues that Plautine comedy is slave theater and that slave audience would certainly be familiar with tetradrachms. These mass acts of enslavement and their potential for movement of knowledge is well illustrated here:

[Flamininus] asked [the Greeks] to find out any Roman citizens who were living as slaves amongst them and send them within two months’ time to him in Thessaly. They would not, he felt sure, think it right or honourable for their liberators to be in the position of slaves in the land which they had liberated. They all exclaimed that among the other things for which they were grateful they thanked him especially for reminding them of so sacred and imperative a duty. There was an immense number who had been made prisoners in the Punic War, and as they were not ransomed by their countrymen Hannibal sold them as slaves. That they were very numerous is evident from what Polybius says. He asserts that this undertaking cost the Achaeans 100 talents, as they fixed the price to be paid to the owners at 500 denarii a head. On this reckoning Achaia must have held 1200 of them; you can estimate proportionally what was the probable number throughout Greece.

Livy 34.50

I’d also note that tetradrachms were produced by some mints of Magna Grecia and A TON of tetradrachms were produced on Sicily by Syracuse and the Carthaginians. The latter specifically imitating Alexander’s coinages.

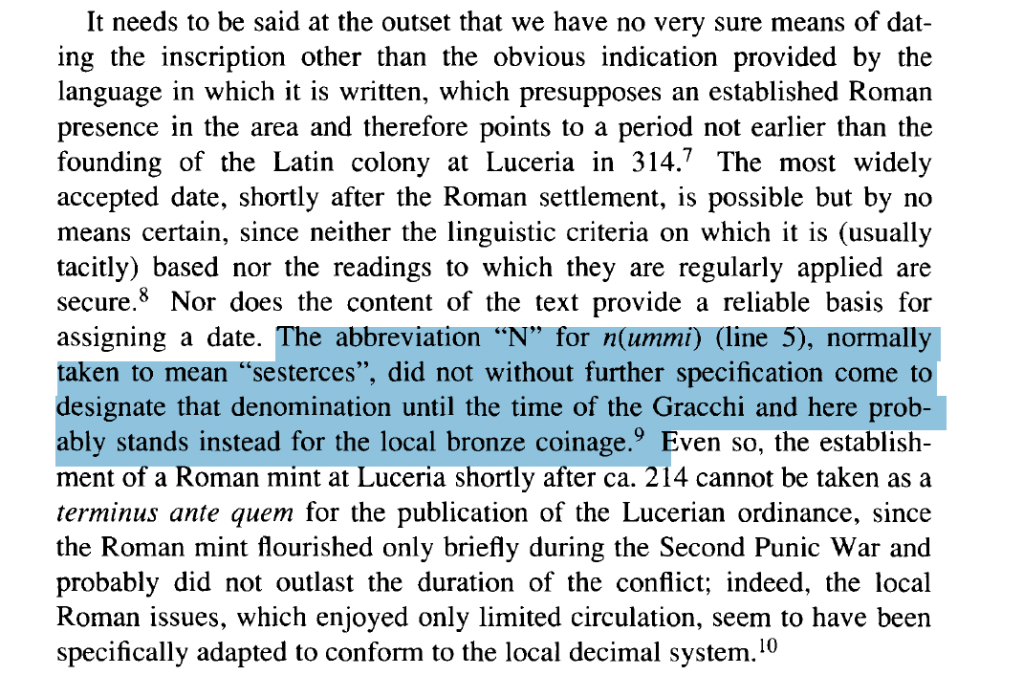

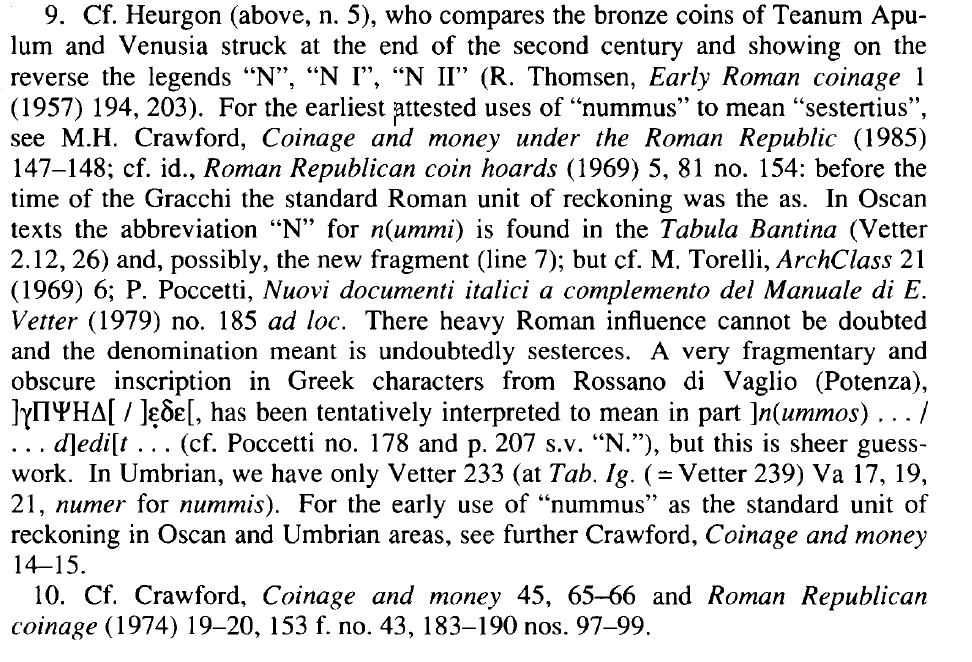

De Callataÿ is correct that nummus could mean tetradrachm in many places in Plautus, but I’m not convinced this is what it must mean. We’re out of luck for earlier literary Latin giving us clues, but we can get some help from epigraphy. I lean towards it meaning simply COIN and to an italic audience it would mean whatever happens to be local unit of account.

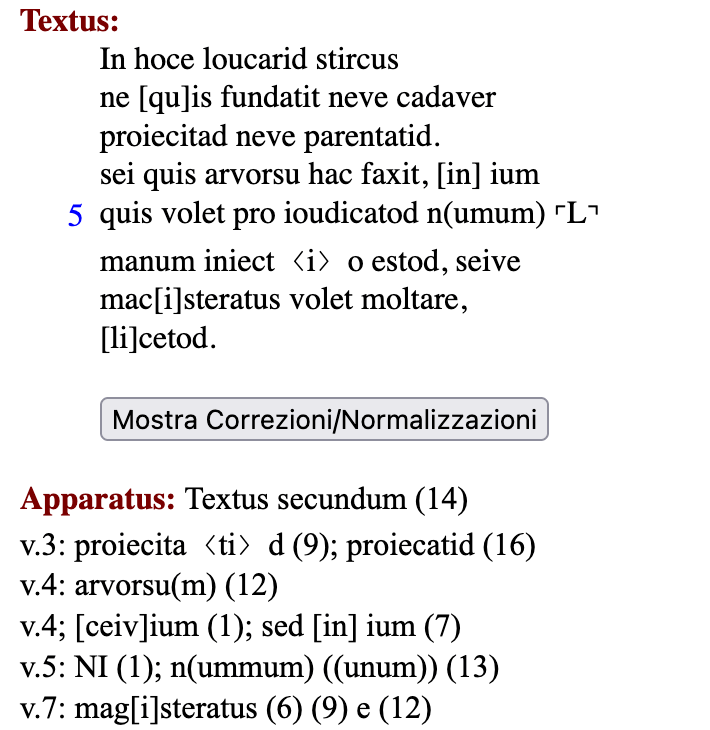

Our earliest testimony for the term nummus that I know of is from an inscription found at Luceria, and lately the preferred date is between 314-250 BCE.

Bodel back in 1994 argued it could be as late as the Gracchi; this seems too late for all the -d endings.

Rutter in Historia Numorum Italy records no types for Venusia with N, and does record two bronze types 698 and 703 that do have an N. The former looks much like the Apollo/man-faced bull bronzes found through out southern italy and associated with Naples. It would need no denomination mark and the N is often replaced with a club. Maybe, just maybe, I might be able to be convinced the N on the 703 is an indication of denomination and stands for Nummus, but I kind of doubt it. I cannot think of any parallels where the name of the denomination is recorded on the coin even if sometimes we have marks of value.

Generally speaking, I don’t think we have to worry too much about what nummus means in Plautus beyond, its a coined piece of money and in the plural typically means something like ‘cash’. In Cato (Agr. 14.3.7) and Lucilius (e.g. frag. 1250) it is used with this generic meaning.

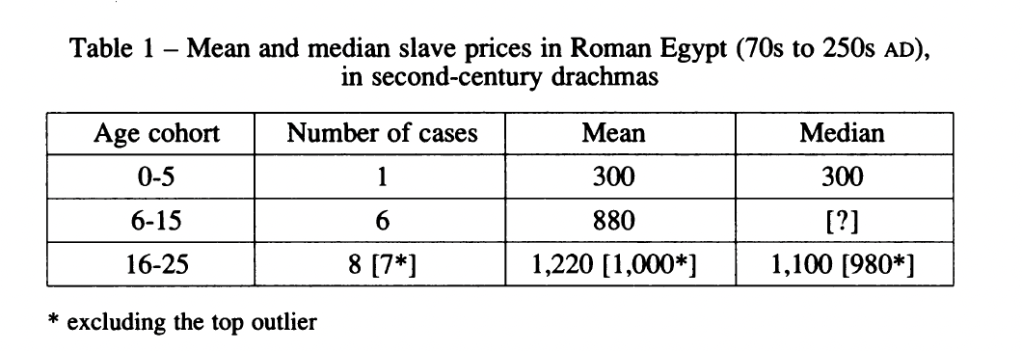

To convince his reader that nummus in Plautus most commonly means specifically a tetradrachm, De Callataÿ puts a great deal of weight on what is an “appropriate” price for a slave. I’m not convinced by this logic as prices of slaves vary greatly and I could if chose find parallels for numbers in asses paid for slaves. Compare above the 500 denarii per enslaved Roman attested c. 196 BCE. Or the following testimony from actual sales in Egypt:

Fundamentally to the plot and for the audience the numbers for the cost of freeing a slave are meant to mean A LOT coins. Could they refer to tetradrachms? Absolutely, but it isn’t necessary for the audience to enjoy the play.

I am more convinced by De Callataÿ’ observations that other Greek denominations are given their true names. This seems a plausible argument in favor of his reading of nummus as tetradrachm.

Of course the trinummus is not a sestertius but De Callataÿ has undervalued and misdescribed it. In the time of Plautus and Terence the sestertius was 2.5 asses, 1/4 a denarius, and very much a silver coin. Eventually it is retariffed at 4 asses but remains silver until the imperial period. It would be a very low single-day’s wage but not wholly inconceivable: remember a soldiers stipendium was 10 asses every 3 days. My guess is that most Romans in the audience would have assumed that a nummus was an AS that was the unit of account.

Romans struck their own gold in the age of Plautus and Terence.

The gold of the plays is reflecting a monetized use of gold very in line with the historical realities he describes. But to continue pushing back a little. In a society where gold has never really been used as money and typically money has been heavy bronze, it is significant that these plays are being staged at least for Plautus’ early productions when the Roman state has decided it must strike gold and we get all of a sudden the oath scene gold and then the mars eagle. It may even give us context for the failed experiment of the Flamininus stater which is very much based on the very goldphilips so common in these comedies. (RR gold issues before 189 BCE). The Roman gold will fall out of circulation just like the Hellenistic did, but to the most contemporary audiences it would be a well-known artifact of recent wars. Gold is unusual and this is what makes it a good plot point for motivating characters.

I love this partly because it recalls gold statues sent to Rome in this very period. I can imagine this detail being written in as the audience knows that Hiero’s gold statue is being melted down to pay their own soldiers.

In sum, believe De Callataÿ, but also consider that Rome was very much a part of not separate from the rest of the Hellenistic world.

One thought on “Reprising De Callataÿ on Plautus”