Final Slides:

Dionysius, R.A. 2.3-6, Loeb Text and Translation

| III. Ἐπεὶ οὖν ἥ τε τάφρος αὐτοῖς ἐξείργαστο καὶ τὸ ἔρυμα τέλος εἶχεν αἵ τε οἰκήσεις τὰς ἀναγκαίους κατασκευὰς ἀπειλήφεσαν, ἀπῄτει δ᾿ ὁ καιρὸς καὶ περὶ κόσμου πολιτείας ᾧ χρήσονται σκοπεῖν, ἀγορὰν ποιησάμενος αὐτῶν ὁ Ῥωμύλος ὑποθεμένου τοῦ μητροπάτορος καὶ διδάξαντος ἃ χρὴ λέγειν, τὴν μὲν πόλιν ἔφη ταῖς τε δημοσίαις καὶ ταῖς ἰδίαις κατασκευαῖς ὡς νεόκτιστον ἀποχρώντως κεκοσμῆσθαι· ἠξίου δ᾿ ἐνθυμεῖσθαι πάντας ὡς οὐ ταῦτ᾿ ἐστὶ τὰ πλείστου ἄξια ἐν ταῖς πόλεσιν. οὔτε γὰρ ἐν τοῖς ὀθνείοις πολέμοις τὰς βαθείας τάφρους καὶ τὰ ὑψηλὰ ἐρύματα ἱκανὰ εἶναι τοῖς ἔνδον ἀπράγμονα σωτηρίας ὑπόληψιν παρασχεῖν, ἀλλ᾿ ἕν τι μόνον ἐγγυᾶσθαι, τὸ μηθὲν ἐξ ἐπιδρομῆς κακὸν ὑπ᾿ ἐχθρῶν παθεῖν προκαταληφθέντας, οὔθ᾿ ὅταν ἐμφύλιοι ταραχαὶ τὸ κοινὸν κατάσχωσι, τῶν ἰδίων οἴκων καὶ ἐνδιαιτημάτων τὰς καταφυγὰς ὑπάρχειν τινὶ ἀκινδύνους. σχολῆς γὰρ ἀνθρώποις ταῦτα καὶ ῥᾳστώνης βίων εὑρῆσθαι παραμύθια, μεθ᾿ ὧν οὔτε τὸ ἐπιβουλεῦον τῶν πέλας κωλύεσθαι μὴ οὐ πονηρὸν εἶναι οὔτ᾿ ἐν τῷ ἀκινδύνῳ βεβηκέναι θαρρεῖν τὸ ἐπιβουλευόμενον, πόλιν τε οὐδεμίαν πω τούτοις ἐκλαμπρυνθεῖσαν ἐπὶ μήκιστον εὐδαίμονα γενέσθαι καὶ μεγάλην, οὐδ᾿ αὖ παρὰ τὸ μὴ τυχεῖν τινὰ κατασκευῆς ἰδίας τε καὶ δημοσίας πολυτελοῦς κεκωλῦσθαι μεγάλην γενέσθαι καὶ εὐδαίμονα· ἀλλ᾿ ἕτερα εἶναι τὰ σώζοντα καὶ ποιοῦντα μεγάλας ἐκ μικρῶν τὰς πόλεις· ἐν μὲν τοῖς ὀθνείοις πολέμοις τὸ διὰ τῶν ὅπλων κράτος, τοῦτο δὲ τόλμῃ παραγίνεσθαι καὶ μελέτῃ, ἐν δὲ ταῖς ἐμφυλίοις ταραχαῖς τὴν τῶν πολιτευομένων ὁμοφροσύνην, ταύτην δὲ τὸν σώφρονα καὶ δίκαιον ἑκάστου βίον ἀπέφηνεν ἱκανώτατον ὄντα τῷ κοινῷ παρασχεῖν. τοὺς δὴ τὰ πολέμιά τε ἀσκοῦντας καὶ τῶν ἐπιθυμιῶν κρατοῦντας ἄριστα κοσμεῖν τὰς ἑαυτῶν πατρίδας τείχη τε ἀνάλωτα τῷ κοινῷ καὶ καταγωγὰς τοῖς ἑαυτῶν βίοις ἀσφαλεῖς τούτους εἶναι τοὺς παρασκευαζομένους μαχητὰς δέ γε καὶ δικαίους ἄνδρας καὶ τὰς ἄλλας ἀρετὰς ἐπιτηδεύοντας τὸ τῆς πολιτείας σχῆμα ποιεῖν τοῖς φρονίμως αὐτὸ καταστησαμένοις, μαλθακούς τε αὖ καὶ πλεονέκτας καὶ δούλους αἰσχρῶν ἐπιθυμιῶν τὰ πονηρὰ ἐπιτηδεύματα ἐπιτελεῖν. ἔφη τε παρὰ τῶν πρεσβυτέρων καὶ διὰ πολλῆς ἱστορίας ἐληλυθότων ἀκούειν, ὅτι πολλαὶ μὲν ἀποικίαι μεγάλαι καὶ εἰς εὐδαίμονας ἀφικόμεναι τόπους αἱ μὲν αὐτίκα διεφθάρησαν εἰς στάσεις ἐμπεσοῦσαι, αἱ δ᾿ ὀλίγον ἀντισχοῦσαι χρόνον ὑπήκοοι τοῖς πλησιοχώροις ἠναγκάσθησαν γενέσθαι καὶ ἀντὶ κρείττονος χώρας ἣν κατέσχον, τὴν χείρονα τύχην διαλλάξασθαι δοῦλαι ἐξ ἐλευθέρων γενόμεναι· ἕτεραι δ᾿ ὀλιγάνθρωποι καὶ εἰς χωρία οὐ πάνυ σπουδαῖα παραγενόμεναι ἐλεύθεραι μὲν πρῶτον, ἔπειτα δ᾿ ἑτέρων ἄρχουσαι διετέλεσαν· καὶ οὔτε ταῖς εὐπραγίαις τῶν ὀλίγων οὔτε ταῖς δυστυχίαις τῶν πολλῶν ἕτερόν τι ἢ τὸ τῆς πολιτείας σχῆμα ὑπάρχειν αἴτιον. εἰ μὲν οὖν μία τις ἦν παρὰ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις βίου τάξις ἡ ποιοῦσα εὐδαίμονας τὰς πόλεις, οὐ χαλεπὴν ἂν γενέσθαι σφίσι τὴν αἵρεσιν αὐτῆς· νῦν δ᾿ ἔφη πολλὰς πυνθάνεσθαι τὰς κατασκευὰς παρ᾿ Ἕλλησί τε καὶ βαρβάροις ὑπαρχούσας, τρεῖς δ᾿ ἐξ ἁπασῶν ἐπαινουμένας μάλιστα ὑπὸ τῶν χρωμένων ἀκούειν, καὶ τούτων οὐδεμίαν εἶναι τῶν πολιτειῶν εἰλικρινῆ, προσεῖναι δέ τινας ἑκάστῃ κῆρας συμφύτους, ὥστε χαλεπὴν αὐτῶν εἶναι τὴν αἵρεσιν. ἠξίου τε αὐτοὺς βουλευσαμένους ἐπὶ σχολῆς εἰπεῖν εἴτε ὑφ᾿ ἑνὸς ἄρχεσθαι θέλουσιν ἀνδρὸς εἴτε ὑπ᾿ ὀλίγων εἴτε νόμους καταστησάμενοι πᾶσιν ἀποδοῦναι τὴν τῶν κοινῶν προστασίαν. “Ἐγὼ δ᾿ ὑμῖν,” ἔφη, “πρὸς ἣν ἂν καταστήσησθε πολιτείαν εὐτρεπής, καὶ οὔτε ἄρχειν ἀπαξιῶ οὔτε ἄρχεσθαι ἀναίνομαι. τιμῶν δέ, ἅς μοι προσεθήκατε ἡγεμόνα με πρῶτον ἀποδείξαντες τῆς ἀποικίας, ἔπειτα καὶ τῇ πόλει τὴν ἐπωνυμίαν ἐπ᾿ ἐμοῦ θέντες, ἅλις ἔχω. ταύτας γὰρ οὔτε πόλεμος ὑπερόριος οὔτε στάσις ἐμφύλιος οὔτε ὁ πάντα μαραίνων τὰ καλὰ χρόνος ἀφαιρήσεταί με οὔτε ἄλλη τύχη παλίγκοτος οὐδεμία· ἀλλὰ καὶ ζῶντι καὶ τὸν βίον ἐκλιπόντι τούτων ὑπάρξει μοι τῶν τιμῶν παρὰ πάντα τὸν λοιπὸν αἰῶνα τυγχάνειν.” IV Τοιαῦτα μὲν ὁ Ῥωμύλος ἐκ διδαχῆς τοῦ μητροπάτορος, ὥσπερ ἔφην, ἀπομνημονεύσας ἐν τοῖς πλήθεσιν ἔλεξεν. οἱ δὲ βουλευσάμενοι κατὰ σφᾶς αὐτοὺς ἀποκρίνονται τοιάδε· “Ἡμεῖς πολιτείας μὲν καινῆς οὐδὲν δεόμεθα, τὴν δ᾿ ὑπὸ τῶν πατέρων δοκιμασθεῖσαν εἶναι κρατίστην παραλαβόντες οὐ μετατιθέμεθα, γνώμῃ τε ἑπόμενοι τῶν παλαιοτέρων, οὓς ἀπὸ μείζονος οἰόμεθα φρονήσεως αὐτὴν καταστήσασθαι, καὶ τύχῃ ἀρεσκόμενοι οὐ γὰρ τήνδε μεμψαίμεθ᾿ ἂν εἰκότως, ἣ παρέσχεν ἡμῖν βασιλευομένοις τὰ μέγιστα τῶν ἐν ἀνθρώποις ἀγαθῶν, ἐλευθερίαν τε καὶ ἄλλων ἀρχήν. περὶ μὲν δὴ πολιτείας ταῦτα ἐγνώκαμεν· τὴν δὲ τιμὴν ταύτην οὐχ ἑτέρῳ τινὶ μᾶλλον ἢ σοὶ προσήκειν ὑπολαμβάνομεν τοῦ τε βασιλείου γένους ἕνεκα καὶ ἀρετῆς, μάλιστα δ᾿ ὅτι τῆς ἀποικίας ἡγεμόνι κεχρήμεθά σοι καὶ πολλὴν σύνισμεν δεινότητα, πολλὴν δὲ σοφίαν, οὐ λόγῳ μᾶλλον ἢ ἔργῳ μαθόντες.” ταῦτα ὁ Ῥωμύλος ἀκούσας ἀγαπᾶν μὲν ἔφη βασιλείας ἄξιος ὑπ᾿ ἀνθρώπων κριθείς· οὐ μέντοι γε λήψεσθαι τὴν τιμὴν πρότερον, ἐὰν μὴ καὶ τὸ δαιμόνιον ἐπιθεσπίσῃ δι᾿ οἰωνῶν αἰσίων. V. Ὡς δὲ κἀκείνοις ἦν βουλομένοις προειπὼν ἡμέραν, ἐν ᾗ διαμαντεύσασθαι περὶ τῆς ἀρχῆς ἔμελλεν, ἐπειδὴ καθῆκεν ὁ χρόνος ἀναστὰς περὶ τὸν ὄρθρον ἐκ τῆς σκηνῆς προῆλθεν· στὰς δὲ ὑπαίθριος ἐν καθαρῷ χωρίῳ καὶ προθύσας ἃ νόμος ἦν εὔχετο Διί τε βασιλεῖ καὶ τοῖς ἄλλοις θεοῖς, οὓς ἐποιήσατο τῆς ἀποικίας ἡγεμόνας, εἰ βουλομένοις αὐτοῖς ἐστι βασιλεύεσθαι τὴν πόλιν ὑφ᾿ ἑαυτοῦ, σημεῖα οὐράνια φανῆναι καλά. μετὰ δὲ τὴν εὐχὴν ἀστραπὴ διῆλθεν ἐκ τῶν ἀριστερῶν ἐπὶ τὰ δεξιά. τίθενται δὲ Ῥωμαῖοι τὰς ἐκ τῶν ἀριστερῶν ἐπὶ τὰ δεξιὰ ἀστραπὰς αἰσίους, εἴτε παρὰ Τυρρηνῶν διδαχθέντες, εἴτε πατέρων καθηγησαμένων, κατὰ τοιόνδε τινά, ὡς ἐγὼ πείθομαι, λογισμόν, ὅτι καθέδρα μέν ἐστι καὶ στάσις ἀρίστη τῶν οἰωνοῖς μαντευομένων ἡ βλέπουσα πρὸς ἀνατολάς, ὅθεν ἡλίου τε ἀναφοραὶ γίνονται καὶ σελήνης καὶ ἀστέρων πλανήτων τε καὶ ἀπλανῶν, ἥ τε τοῦ κόσμου περιφορά, δι᾿ ἣν τοτὲ μὲν ὑπὲρ γῆς ἅπαντα τὰ ἐν αὐτῷ γίνεται, τοτὲ δὲ ὑπὸ γῆς, ἐκεῖθεν ἀρξαμένη τὴν ἐγκύκλιον ἀποδίδωσι κίνησιν. τοῖς δὲ πρὸς ἀνατολὰς βλέπουσιν ἀριστερὰ μὲν γίνεται τὰ πρὸς τὴν ἄρκτον ἐπιστρέφοντα μέρη, δεξιὰ δὲ τὰ πρὸς μεσημβρίαν φέροντα· τιμιώτερα δὲ τὰ πρότερα πέφυκεν εἶναι τῶν ὑστέρων. μετεωρίζεται γὰρ ἀπὸ τῶν βορείων μερῶν ὁ τοῦ ἄξονος πόλος, περὶ ὃν ἡ τοῦ κόσμου στροφὴ γίνεται, καὶ τῶν πέντε κύκλων τῶν διεζωκότων τὴν σφαῖραν ὁ καλούμενος ἀρκτικὸς ἀεὶ τῇδε φανερός· ταπεινοῦται δ᾿ ἀπὸ τῶν νοτίων ὁ καλούμενος ἀνταρκτικὸς κύκλος ἀφανὴς κατὰ τοῦτο τὸ μέρος. εἰκὸς δὴ κράτιστα τῶν οὐρανίων καὶ μεταρσίων σημείων ὑπάρχειν, ὅσα ἐκ τοῦ κρατίστου γίνεται μέρους, ἐπειδὴ δὲ τὰ μὲν ἐστραμμένα πρὸς τὰς ἀνατολὰς ἡγεμονικωτέραν μοῖραν ἔχει τῶν προσεσπερίων, αὐτῶν δέ γε τῶν ἀνατολικῶν ὑψηλότερα τὰ βόρεια τῶν νοτίων, ταῦτα ἂν εἴη κράτιστα ὡς δέ τινες ἱστοροῦσιν ἐκ παλαιοῦ τε καὶ πρὶν ἢ παρὰ Τυρρηνῶν μαθεῖν τοῖς Ῥωμαίων προγόνοις αἴσιοι ἐνομίζοντο αἱ ἐκ τῶν ἀριστερῶν ἀστραπαί. Ἀσκανίῳ γὰρ τῷ ἐξ Αἰνείου γεγονότι, καθ᾿ ὃν χρόνον ὑπὸ Τυρρηνῶν, οὓς ἦγε βασιλεὺς Μεσέντιος, ἐπολεμεῖτο καὶ τειχήρης ἦν, περὶ τὴν τελευταίαν ἔξοδον, ἣν ἀπεγνωκὼς ἤδη τῶν πραγμάτων ἔμελλε ποιεῖσθαι, μετ᾿ ὀλοφυρμοῦ τόν τε Δία καὶ τοὺς ἄλλους αἰτουμένῳ θεοὺς αἴσια σημεῖα δοῦναι τῆς ἐξόδου φασὶν αἰθρίας οὔσης ἐκ τῶν ἀριστερῶν ἀστράψαι τὸν οὐρανόν. τοῦ δ᾿ ἀγῶνος ἐκείνου λαβόντος τὸ κράτιστον τέλος διαμεῖναι παρὰ τοῖς ἐκγόνοις αὐτοῦ νομιζόμενον αἴσιον τόδε τὸ σημεῖον. VI. Τότε δ᾿ οὖν ὁ Ῥωμύλος ἐπειδὴ τὰ παρὰ τοῦ δαιμονίου βέβαια προσέλαβε, συγκαλέσας τὸν δῆμον εἰς ἐκκλησίαν καὶ τὰ μαντεῖα δηλώσας βασιλεὺς ἀποδείκνυται πρὸς αὐτῶν καὶ κατεστήσατο ἐν ἔθει τοῖς μετ᾿ αὐτὸν ἅπασι μήτε βασιλείας μήτε ἀρχὰς λαμβάνειν, ἐὰν μὴ καὶ τὸ δαιμόνιον αὐτοῖς ἐπιθεσπίσῃ, διέμεινέ τε μέχρι πολλοῦ φυλαττόμενον ὑπὸ Ῥωμαίων τὸ περὶ τοὺς οἰωνισμοὺς νόμιμον, οὐ μόνον βασιλευομένης τῆς πόλεως, ἀλλὰ καὶ μετὰ κατάλυσιν τῶν μονάρχων ἐν ὑπάτων καὶ στρατηγῶν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων τῶν κατὰ νόμους ἀρχόντων αἱρέσει. πέπαυται δ᾿ ἐν τοῖς καθ᾿ ἡμᾶς χρόνοις, πλὴν οἷον εἰκών τις αὐτοῦ λείπεται τῆς ὁσίας αὐτῆς ἕνεκα γινομένη ἐπαυλίζονται μὲν γὰρ οὶ τὰς ἀρχὰς μέλλοντες λαμβάνειν καὶ περὶ τὸν ὄρθρον ἀνιστάμενοι ποιοῦνταί τινας εὐχὰς ὑπαίθριοι, τῶν δὲ παρόντων τινὲς ὀρνιθοσκόπων μισθὸν ἐκ τοῦ δημοσίου φερόμενοι ἀστραπὴν αὐτοῖς σημαίνειν ἐκ τῶν ἀριστερῶν φασιν τὴν οὐ γενομένην. οἱ δὲ τὸν ἐκ τῆς φωνῆς οἰωνὸν λαβόντες ἀπέρχονται τὰς ἀρχὰς παραληψόμενοι οἱ μὲν αὐτὸ τοῦθ᾿ ἱκανὸν ὑπολαμβάνοντες εἶναι τὸ μηδένα γενέσθαι τῶν ἐναντιουμένων τε καὶ κωλυόντων οἰωνῶν, οἱ δὲ καὶ παρὰ τὸ βούλημα τοῦ θεοῦ, ἔστι γὰρ ὅτε βιαζόμενοι καὶ τὰς ἀρχὰς ἁρπάζοντες μᾶλλον ἢ λαμβάνοντες. δι᾿ οὓς πολλαὶ μὲν ἐν γῇ στρατιαὶ Ῥωμαίων ἀπώλοντο πανώλεθροι, πολλοὶ δ᾿ ἐν θαλάττῃ στόλοι διεφθάρησαν αὔτανδροι, ἄλλαι τε μεγάλαι καὶ δειναὶ περιπέτειαι τῇ πόλει συνέπεσον αἱ μὲν ἐν ὀθνείοις πολέμοις, αἱ δὲ κατὰ τὰς ἐμφυλίους διχοστασίας, ἐμφανεστάτη δὲ καὶ μεγίστη κατὰ τὴν ἐμὴν ἡλικίαν, ὅτε Λικίννιος Κρᾶσσος ἀνὴρ οὐδενὸς δεύτερος τῶν καθ᾿ ἑαυτὸν ἡγεμόνων στρατιὰν ἦγεν ἐπὶ τὸ Πάρθων ἔθνος, ἐναντιουμένου τοῦ δαιμονίου πολλὰ χαίρειν φράσας τοῖς ἀποτρέπουσι τὴν ἔξοδον οἰωνοῖς μυρίοις ὅσοις γενομένοις. ἀλλ᾿ ὑπὲρ μὲν τῆς εἰς τὸ δαιμόνιον ὀλιγωρίας, ᾗ χρῶνταί τινες ἐν τοῖς καθ᾿ ἡμᾶς χρόνοις, πολὺ ἔργον ἂν εἴη λέγειν. VII. Ὁ δὲ Ῥωμύλος ἀποδειχθεὶς τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον ὑπό τε ἀνθρώπων καὶ θεῶν βασιλεὺς τά τε πολέμια δεινὸς καὶ φιλοκίνδυνος ὁμολογεῖται … | III. When, therefore, the ditch was finished, the rampart completed and the necessary work on the houses done, and the situation required that they should consider also what form of government they were going to have, Romulus called an assembly by the advice of his grandfather, who had instructed him what to say, and told them that the city, considering that it was newly built, was sufficiently adorned both with public and private buildings; but he asked them all to bear in mind that these were not the most valuable things in cities. For neither in foreign wars, he said, are deep ditches and high ramparts sufficient to give the inhabitants an undisturbed assurance of their safety, but guarantee one thing only, namely, that they shall suffer no harm through being surprised by an incursion of the enemy; nor, again, when civil commotions afflict the State, do private houses and dwellings afford anyone a safe retreat. For these have been contrived by men for the enjoyment of leisure and tranquillity in their lives, and with them neither those of their neighbours who plot against them are prevented from doing mischief nor do those who are plotted against feel any confidence that they are free from danger; and no city that has gained splendour from these adornments only has ever yet become prosperous and great for a long period, nor, again, has any city from a want of magnificence either in public or in private buildings ever been hindered from becoming great and prosperous. But it is other things that preserve cities and make them great from small beginnings: in foreign wars, strength in arms, which is acquired by courage and exercise; and in civil commotions, unanimity among the citizens, and this, he showed, could be most effectually achieved for the commonwealth by the prudent and just life of each citizen. Those who practise warlike exercises and at the same time are masters of their passions are the greatest ornaments to their country, and these are the men who provide both the commonwealth with impregnable walls and themselves in their private lives with safe refuges; but men of bravery, justice and the other virtues are the result of the form of government when this has been established wisely, and, on the other hand, men who are cowardly, rapacious and the slaves of base passions are the product of evil institutions. He added that he was informed by men who were older and had wide acquaintance with history that of many large colonies planted in fruitful regions some had been immediately destroyed by falling into seditions, and others, after holding out for a short time, had been forced to become subject to their neighbours and to exchange their more fruitful country for a worse fortune, becoming slaves instead of free men; while others, few in numbers and settling in places that were by no means desirable, had continued, in the first place, to be free themselves, and, in the second place, to command others; and neither the successes of the smaller colonies nor the misfortunes of those that were large were due to any other cause than their form of government. If, therefore, there had been but one mode of life among all mankind which made cities prosperous, the choosing of it would not have been difficult for them; but, as it was, he understood there were many types of government among both the Greeks and barbarians, and out of all of them he heard three especially commended by those who had lived under them, and of these systems none was perfect, but each had some fatal defects inherent in it, so that the choice among them was difficult. He therefore asked them to deliberate at leisure and say whether they would be governed by one man or by a few, or whether they would establish laws and entrust the protection of the public interests to the whole body of the people. “And whichever form of government you establish,” he said, “I am ready to comply with your desire, for I neither consider myself unworthy to command nor refuse to obey. So far as honours are concerned, I am satisfied with those you have conferred on me, first, by appointing me leader of the colony, and, again, by giving my name to the city. For of these neither a foreign war nor civil dissension nor time, that destroyer of all that is excellent, nor any other stroke of hostile fortune can deprive me; but both in life and in death these honours will be mine to enjoy for all time to come.” IV. Such was the speech that Romulus, following the instructions of his grandfather, as I have said, among the masses. And they, having consulted together by themselves, returned this answer: “We have no need of a new form of government and we are not going to change the one which our ancestors approved of as the best and handed down to us. In this we show both a deference for the judgment of our elders, whose superior wisdom we recognize in establishing it, and our own satisfaction with our present condition. For we could not reasonably complain of this form of government, which has afforded us under our kings the greatest of human blessings—liberty and the rule over others. Concerning the form of government, then, this is our decision; and to this honour we conceive none has so good a title as you yourself by reason both of your royal birth and of your merit, but above all because we have had you as the leader of our colony and recognize in you great ability and great wisdom, which we have seen displayed quite as much in your actions as in your words.” Romulus, hearing this, said it was a great satisfaction to him to be judged worthy of the kingly office by his fellow men, but that he would not accept the honour until the divine, too, had given its sanction by favourable omens. V. And when this was approved, he appointed a day on which he proposed to consult the auspices concerning the sovereignty; and when the time was come, he rose at break of day and went forth from his tent. Then, taking his stand under the open sky in a clear space and first offering the customary sacrifice, he prayed to King Jupiter and to the other gods whom he had chosen for the patrons of the colony, that, if it was then pleasure he should be king of the city, some favourable signs might appear in the sky. After this prayer a flash of lightning darted across the sky from the left to the right. Now the Romans look upon the lightning that passes from the left to the right as a favourable omen, having been thus instructed either by the Tyrrhenians or by their own ancestors. Their reason is, in my opinion, that the best seat and station for those who take the auspices is that which looks toward the east, from whence both the sun and the moon rise as well as the planets and fixed stars; and the revolution of the firmament, by which all things contained in it are sometimes above the earth and sometimes beneath it, begins its circular motion thence. Now to those who look toward the east the parts facing toward the north are on the left and those extending toward the south are on the right, and the former are by nature more honourable than the latter. For in the northern parts the pole of the axis upon which the firmament turns is elevated, and of the five zones which girdle the sphere the one called the arctic zone is always visible on this side; whereas in the southern parts the other zone, called the antarctic, is depressed and invisible on that side. So it is reasonable to assume that those signs in the heavens and in mid-air are the best which appear on the best side; and since the parts that are turned toward the east have preëminence over the western parts, and, of the eastern parts themselves, the northern are higher than the southern, the former would seem to be the best. But some relate that the ancestors of the Romans from very early times, even before they had learned it from the Tyrrhenians, looked upon the lightning that came from the left as a favourable omen. For they say that when Ascanius, the son of Aeneas, was warred upon and besieged by the Tyrrhenians led by their king Mezentius, and was upon the point of making a final sally out of the town, his situation being now desperate, he prayed with lamentations to Jupiter and to the rest of the gods to encourage this sally with favourable omens, and thereupon out of a clear sky there appeared a flash of lightning coming from the left; and as this battle had the happiest outcome, this sign continued to be regarded as favourable by his posterity. VI. When Romulus, therefore, upon the occasion mentioned had received the sanction of the divine also, he called the people together in assembly; and having given them an account of the omens, he was chosen king by them and established it as a custom, to be observed by all his successors, that none of them should accept the office of king or any other magistracy until Heaven, too, had given its sanction. And this custom relating to the auspices long continued to be observed by the Romans, not only while the city was ruled by kings, but also, after the overthrow of the monarchy, in the elections of their consuls, praetors and other legal magistrates; but it has fallen into disuse in our days except as a certain semblance of it remains merely for form’s sake. For those who are about to assume the magistracies pass the night out of doors, and rising at break of day, offer certain prayers under the open sky; whereupon some of the augurs present, who are paid by the State, declare that a flash of lightning coming from the left has given them a sign, although there really has not been any. And the others, taking their omen from this report, depart in order to take over their magistracies, some of them assuming this alone to be sufficient, that no omens have appeared opposing or forbidding their intended action, others acting even in opposition to the will of the god; indeed, there are times when they resort to violence and rather seize than receive the magistracies. Because of such men many armies of the Romans have been utterly destroyed on land, many fleets have been lost with all their people at sea, and other great and dreadful reverses have befallen the commonwealth, some in foreign wars and others in civil dissensions. But the most remarkable and the greatest instance happened in my time when Licinius Crassus, a man inferior to no commander of his age, led his army against the Parthian nation contrary to the will of Heaven and in contempt of the innumerable omens that opposed his expedition. But to tell about the contempt of the divine power that prevails among some people in these days would be a long story. VII. Romulus, who was thus chosen king by both men and gods, is allowed to have been a man of great military ability and personal bravery … |

Acknowledgement of Writing Process and Peer Feedback

I owe a debt of gratitude to Eric Orlin and Claude Eilers who answered the below request, read a draft, and helped me tighten up my presentation and logics. I hope to further engage with their suggestion in a final published version.

I”ve finished a full draft of my conference paper for next Wednesday at Notre Dame. It is my first on strictly historiography in a LONG time. You’ll notice the deck of slides has a suspicious number of coins regardless. If feel I make interesting points but it doesn’t feel yet like a cohesive whole and thus it is less than my best. If you are professional historian/historiographer and want to read my draft for me and offer gentle feedback, I’d be more than grateful. Drop me an email. This offer expires next Monday.

Speaking Notes

Slide 1: For the best part of ten years I’ve been interested in all the places Dionysius breaks the fourth wall to break away from the distant past to remind us of his living present. In breaking the fourth wall he is acknowledging that he has readers, an “I see you seeing me” moment and he is also acknowledging that he exists in a time very different from the one he is describing. We at our great temporal distance are in effect watching him talk to his contemporaries about a shared reality while he is also talking to us about both the his distant past AND his contemporary reality. By regularly acknowledging his own distance and contemporary different he is invited us again and again to compare the two times, to notice the difference, and to draw meaning and relevance from that comparison. One of the most curious among them is a statement that Crassus only fell to the Parthians because he would not heed divine warnings.

Slide 2: Yet, while I was trying to finish a pesky book on coins and clear the decks to get back to this type of historiographical question, other more dedicated minds were engaging with similar problems. I’ve particular admiration for Pelling on Regime Change and Parker on the Gods. I’m struck by how different is Pelling’s reading of Dionysius to my own. Not in care or intention or even in most conclusion, but rather the types of passages that interest us and seem most relevant for the question of Dionysius’ engagement with the contemporary. I was afraid I would have nothing left to say. [But of course we always do!]. Pelling begins with Dionysius’ distain for Polybius and ends by seeing Dionysius in a similar Augustan tradition as Livy and Vergil – not for or against but reflecting the Augustan age and its pre occupatons and dominant narratives.

In a forthcoming piece, I read Dionysius as engaging in polemical self positioning to allow himself to become the new “Timaeus” or rather Polybius prequel, just as Polybius attacks Timaeus in order to establish his own relevance and in the same piece read Dionysius’ views on autocratic rule as very much influenced by contemporary events. So to an extent I agree with Pelling’s much needed treatment of Dionysius’ constitutional views. Yet, I am also curious to the degree Dionysius is still a Greek historian writing in the tradition of Greek historiography.

Parker considers Dionysius’ views of the divine as a reaction to even rejection of past traditions. Overall he agree’s with Cary’s 1937 summary comments in the introduction to the Loeb volume that Dionysius is a true believer in divine intervention in human affairs, damning of atheists, and a distaste for Greek mythology and its shameful portrayals of the gods. Parker says I quote, “In consequence of his strong belief in divine guidance, Dionysius is reserved about the role of Tyche in world affairs.” Parker reads Dionysius as at a distance even in rejection of the tradition of Polybius, and even Livy. He hypothesized that after a period of great skepticism in historiographical and intellectual circles comes a re embracing of traditional religious views. Thus, Parker would place Dionysius and even Diodorus in a model of traditional belief and even anticipating the morality of Plutarch. Parker is apt in his selection of key themes but a bit like Pelling on Polybius, I’m not sure we should be so convinced Dionysius ‘believes’ what he says. In many ways belief and feelings are not the central concern. Dionysius is a master rhetorician in full control of his narrative. He has a purpose for saying what he says. He controls his authorial voice and is keenly aware of his multiple contemporary audiences. Thus, I propose in what follows to observe how he is controlling his presentation and why that might be significant both in determining why he assigns to the divine the roles he does.

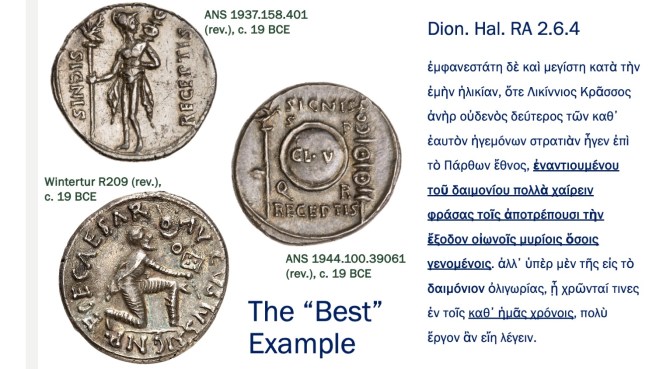

Slide 3: To structure this paper I’m going to start with this short passage and with a relatively close reading of the chapters leading up to this passage before returning briefly to this passage and then broaden out to other evidence and literary passages that might help us contextualize Dionysius perspective. Dionysius claims that Crassus was second to none as a commander, an odd memorialization for a man most often discussed as a power-broker, business man, and hoarder of immense wealth, not for his military prowess. Moreover, we know from Plutarch’s life of Crassus that he was committed to religious observation (at least if it was in his interests) having dedicated a 10th of his wealth to Hercules before setting out on his final campaign. His tithe provided enough food to feed every Roman for three months we’re told as well as all the other ostentatious spectacles. Dionysius ends this small digression with the comment that it would be POLU ERGON, much work, to explain how divine signs had been ignored EMAS CHRONOIS, in our times. Crassus become a synecdoche for all the earlier failings that go unmentioned. Yet we the audience are also invited to fill in the blanks from our own memories of recent events. We are invited to know, or even in terms of today’s pundits “Do Your Own Research”. We are being led to conclusions by a skilled rhetorician who obscures his own role as our guide. If you invite someone to find out for themselves whats ‘really in vaccines’ you’ve already convinced them there is a hidden truth to be found. As we are invited to fill in the long story of religious improprieties we the contemporary audience are already conceding that religion and its right observance are necessary and appropriate for good government.

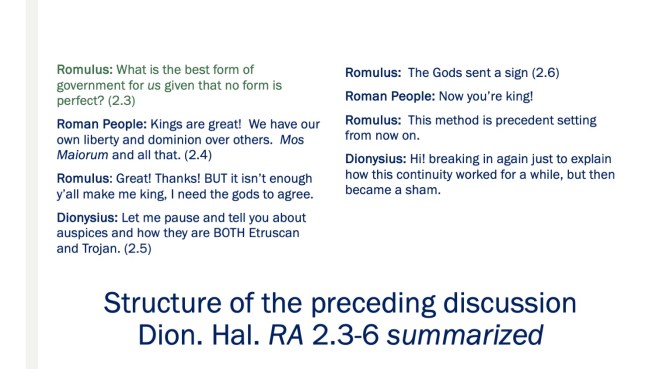

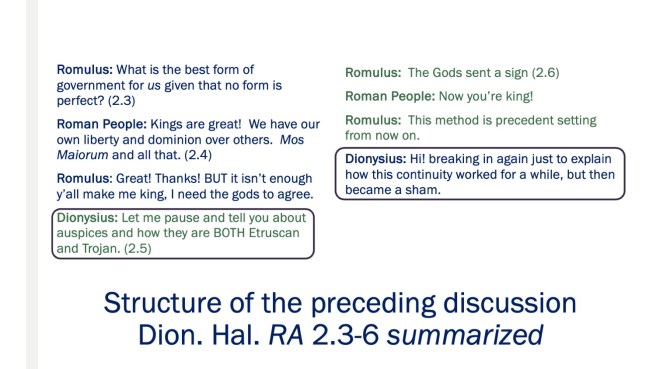

Slide 4: On the slide I give a slightly flippant outline of the material, in the interests of time I’ll only hit a the most relevant points. You can find the whole text and translation on my digital handout. As we move through the outline the portion I’ll be discussing is highlighted in green. The Crassus passage comes within a wider meditation on forms of government and why and how Romulus as law-giver established the state as he did. This shouldn’t surprise us. Religion is almost always presented as key to the Roman constitution, even in Polybius’ skeptical treatment of rituals in book six, he regularly concedes the value of Roman religion for social cohesion and continuity of tradition. I’ve started summarizing at 2.3, three chapters before the passage in question. Romulus assembles the Roman people once the ditch, rampart, and houses are built to decide on a form of government. We’re not told where the assembly was held. Dionysius does not seem to be reflecting on any of the historical assemblies of the Roman people. He does emphasize that Romulus isn’t innovating but instead being advised by his grandfather both in the initiation of the conversation and what needs to be said. The rhetoric attributed to Romulus emphasizes themes of public versus private and internal vs domestic affairs. He dwells on the dangers of enslavement both figuratively and literally. He alludes to three forms of government common to barbarians and Greeks alike. He ends with a statement his honors are already sufficiently enduring; he stresses he will freely step away from the power he presently has.

Slide 5: Chapter 2.4 opens with another reminder that the speech had been advised by Romulus’ grandfather. The people go off to confirm among themselves and they deliver this response. This is super strange. The people are not a deliberative body at Rome. They listen to speeches, elect candidates, and vote yes and no on legislation and guilty non-guilty in trials. Deliberation is the bailiwick of the Roman Senate not the populus. Even in the Senate the ‘debate’ follows a rigorously controlled speaking order. The speaker who replies for the unified whole is not named. He has no characterization at all. Dionysius again wants to present a pair of set speeches, He is most comfortable exploring abstract concepts in the rhetorical genre. Leaving this response to Romulus anonymous and communal allows him to formulate his own answer to his own question in his favorite style without engaging in characterization or further mythologizing. The answer is relatively short by comparison with Romulus’ framing of the ‘question’, just 13 lines of Greek in the Loeb printing compared to more than 60 for the set up. Only three main points are made clear: kingship is acceptable because of (1) the wisdom of the ancestors (2) it has provided freedom internally and dominion externally, and (3) Romulus himself is worthy by deeds and lineage. I take from this confirmation that Dionysius’ emphasis on Romulus’ grandfather is no accident, but rather further emphasis on deference to mos maiorum and filial piety.

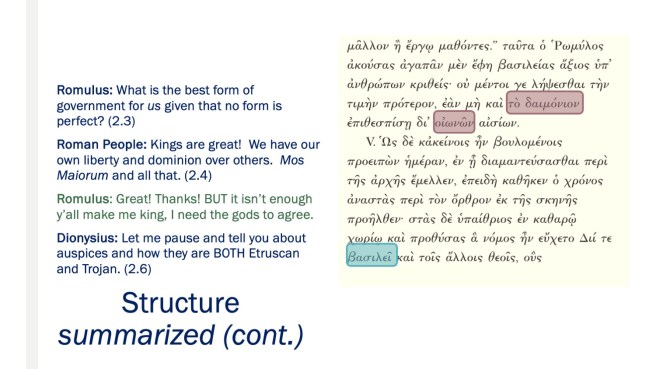

Slide 6: Dionysius is positively laconic (at least for himself) as he states in brief that Romulus would not accept the honors from the people no matter how much they pleased him without divine approval. Notice the combination of TO DAIMONION and OI OIONOI to describe the necessary pre requisites for Romulus’ assumption of the kingship. Dionysius goes on to use the very same vocabulary is used to describe Crassus’ failure to observe divine messages. DAIMONION is a favorite generic and all encompassing reference to divine agency. It is found in History and Philosophy almost from their inception in the Greek language. OIONOS can refer to any large bird of prey but is often found simply to mean omens or signs of any kind. I think in the Roman context and the context of these passages particularly the meaning of birds as a synecdoche for augury is particularly strong.

Dionysius has the people approve Romulus’ decision to consult the gods on the matter; making piety not only a characteristic of the leader but also his followers. It should go without saying this is completely ahistorical and Dionysius constructing an exchange between between ruler and subject without precedence in Roman traditional practices. More typically, the Senate referred religious questions to experts within the priestly college. I can think of no collective approval of religious action by the people that might have inspired Dionysius’ historical creativity here.

Chapter five has Romulus invoke Jupiter as KING to sanctify the use of kingship at Rome. Logical enough and yet again not a common form of address, we might have expected Optimus Maximus or even a whole list of patron gods . The best parallel I have found is in Cassius Dio where Caesar retorts to Antony at the Lupercalia “Jupiter alone is king of the Romans” (44.11.3). The quote is absent from other surviving accounts, but we may have an allusion in Nicolaus of Damascus’ Biography of Augustus (73) where Caesar says the diadem was more appropriate for Jupiter Capitolinus. Even if Dionysius is not trying to make us think of Caesar here, he is certainly drawing a direct connection between the role of the king and divine authority and ideology we won’t see fully expressed until the high Empire. (Trajan coin).

Slide 7: Who are these people Romulus was consulting and what gave them authority to determine the constitution of the state or sanction him to consult the gods on their collective behalf? Is Dionysius situating the Roman people with self determination or implying their sovereignty? I don’t think the text supports these readings. When Romulus had assembled the people to ask the question about the form of government, Dionysius used the term AGORA to denote the collective nature assembly. And when Dionysius sums up the speech he refers to the people as PLETHOS and when Romulus hesitates to receive kingship on their authority alone he calls them ANTHROPOI. We have no use here of DEMOS and it seems striking by its absence. It is only AFTER Romulus reports the sign, becomes king, and establishes a lasting precede that the language of a political body is used in the text. It is only now that the people become a DEMOS and their gathering a a proper EKKLESIA in Dionysius’ choice of language. Divine sanction seems to have been necessary in Dionysius’ mind for Romulus’ status but also for the establishment of the civic body as a body. The people and the gods make a king, but the king and gods also make a people into a legitimate civic body.

Slide 8: I’m now skipping over Dionysius’ extended digression on the auspices involving lightening, in which he endeavors to show is how ”scientific” especially geographical knowledge. The digression allows him to play cultural interpreter for his Greek audience, deepening his own authority on all matters Roman. The next portion of narration wherein Romulus reports the sign, becomes king, and establishes a last precede is very short before we have yet another digression on continuity of the tradition and its failure. The two digressions are doing very different work in the narrative. Whereas the first situates Dionysius as an anthropologist and guide to foreign esoteric practices, the second has Dionysius comment on the contemporary relevance of the past for the present. We can dismiss this as the rhetoric of the decline that justifies the augustan restoration, but we can also observe HOW Dionysius’ rhetorically brings his reader to concede to this world view, largely by refusing to engage with specifics.

Slide 9: Dionysius contrasts the authentic, even scientific, interpretation of the omens that were present for Romulus with the ritualized practices of his own day. Part of the disconnect is that the incumbent magistrates do not need to see the omen themselves, the responsibility for the observation is abrogated to some so-called “bird watchers” under state employ. These individuals lie and their lie is taken as a positive omen. Dionysius using direct authorial voice to leave us no doubt of the disjoin of what is said and the real events.

[CUT from actual talk: I’m interested in the apparent perjorative treatment of these ORNITHOSKOPOI and I’m hoping in discussion some of you might have ideas either who these individuals might have really been in Rome’s complex religious structures, I doubt they can be augurs based on their being ‘employed’, but perhaps I’m wrong. I’m also interested if you can help me nuance out the nature of distain and how it might connect to other polemical attitudes.]

Slide 10: Before Dionysius coming to Crassus his ultimate and best example, he engages in sweeping generalities. The consequences for ignoring divine will are evident on land and sea, in foreign and domestic conflict. All the recent suffering may be laid at the feet of a godless elite who go through the motions of religious observation without any true divine mandate. Are these elected officials really even legitimate leaders of the republic or have they stolen their positions through violence and charlatanry? The contemporary reader is left to fill in the gaps. Are we to think of Antony? Pompey? Sulla? Marius? Crassus is safe — the others all too charged in many ways. The long and the short of the passage is a suggestion a lack of piety by the leaders of the state is key to explaining Rome’s suffering.

Slide 11: Why is Crassus safe? Dionysius’ choice of Crassus intersects with Augustus’ own intensive focus on the return of the Parthian standards as the symbol of his successful restoration of Roman power. The return is all over the coinage immediately after their return. Often associated with Mars Ultor and Augustus’ own Clipeus Virtutis which among other virtues celebrates particularly Augustus’ own piety.

Slide 12: The Augustan celebration of the return of the standards was in no way limited to the coinage. Today the most famous image of the return is on the cuirass of Augustus in the prima porta statue from Livia summer residence, but in antiquity perhaps the most spectacular commemorations may have been on the triumphal arch in the Roman forum. Augustus’ arch or arches are now lost but at least one would have stood between the regia and the temple of Castor and Pollux. We think it may have looked something like this aureus with Parthians flanking Augustus holding out the aquila and standards. Augustus changed the primary meaning of Mars Ultor from a celebration of his avenging his father to his having Avenged Crassus’ defeat. Likewise, if as some believe this arch was originally built to celebrate the victories at Actium and Alexandria then we might be seeing the return of the standards also overwriting yet another civil war victory with a foreign diplomatic success. We cannot know precisely when Dionysius was drafting book 2, yet we do know he arrived in Rome shortly after the defeat of Antony and witnessed first-hand the transformation of the urban landscape and political norms over the next decades.

[Cf. Ovid Fasti 5.560-585 on change of Augustus’ relationship to Ultor and allusion to Romulus]

Slide 13: As Dionysius finishes with Crassus, he brings us back to his historical narration and prepares us to transition into a description of Romulus’ constitution. The words that open that next chapter are at the top of the slide: “thus chosen king by both men and gods”. Dionysius’ Romulus was made king was not his own strength or characteristics alone, nor just popular opinion, but instead a specific combination of divine and human recognition of his qualities and confirmation of his role as king. I see here a precursor to the themes more fully developed by Dio. Dio Book 53 has the famous explanation of the young Caesar’s choice of Augustus as his honorific. Just before the passage on the screen Dio introduces the Romulus theme by connecting Augustus’ home on the Palatine to the location of Romulus’ hut. Next we learn that the young Caesar originally wanted to be called Romulus but had to reject it because of the ‘kingship’ overtones of the name and thus chose instead the religious honorific of Augustus. Dio works to translate and nuance the name for his audience. Dio never fully abandons the Augustus-Romulus connection, even suggesting during his discussion of Augustus deification that the connection was supported perhaps even originated with Livia herself. There is a wide literature on Augustus’ use of Romulus and I propose only to nod in its general direction today to suggest that Augustus was very much in the mind of Dionysius in the construction of this portion of his narrative and his view of the role of the divine.

[Poletti, Beatrice. 2023. “Augustus and the Myth of Romulus (on A. Castiello, Augusto Il Fondatore: La Rinascita Di Roma E Il Mito Romuleo)”. Histos 17 (April). https://doi.org/10.29173/histos552. The Dio passage is sent amongst events of 27 BCE. And Sertorius does not attribute the desire to Augustus himself but only a popular suggestion (Aug. 7 cf. Florus 2.34.66)]

Slide 14: Even if Augustan Rome was steep in the rhetoric of religious renewal, what I want to emphasize is how striking it is for a Greek historian or really any historian to attribute historical events to divine cause. This is very different than how the Greek historians utilize the persona of Tyche; Dionysius’ TO DAIMONION is no theoretical personified abstraction or authorial-thought experiment. Instead, he makes a bold assertion in the authorial voice that religious ritual, the very type of action Polybius happily dismissed as a means to control the lower classes, is in fact a means of ascertaining the will of the gods and its neglect may be a root cause of Rome’s problems. Even Livy who happily reported prodigy after prodigy, does not typically attribute Rome’s fate to supernatural powers. We could brush Dionysius invocation of the divine aside as another sign of his lesser value as a historian or his sycophancy, but I think it is worth pondering this unusual authorial intervention and contextualizing. Dionysius knew his rhetoric and he knew how to stay away from anything that might be too controversial and he certainly has read his Polybius. His near contemporaries such as Nicolaus of Damascus and Livy thread the needle of religiosity very differently. Dionysius need not have included these authorial statements to accomplish his authorial goals so why are they here? As I said at the beginning I am less concerned with what Dionysius believes in his heart of hearts as I’m skeptical we can know this, but rather I’m interested in why he may express these ideas in these particular ways in this particular context.

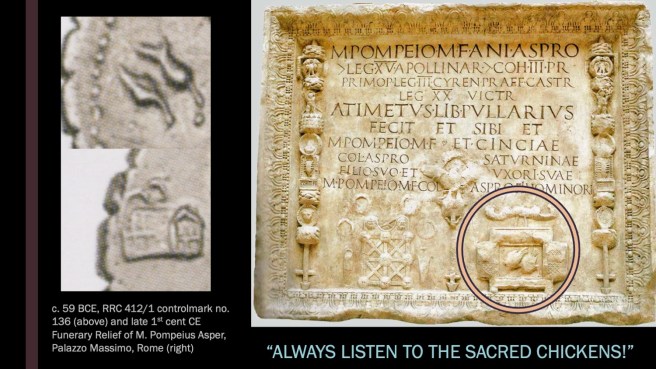

Slide 15: While it is hard to escape the Augustan rhetorical echo chamber, I think one way forward with this passage is to situate it along side other narratives of Roman defeats. Dionysius’ choice to center Crassus’ disregard for the omens as the cause of military disaster calls to mind another Roman disaster more commonly attributed to impiety, the battle of Drepanum in 249 BCE before which P. Claudius Pulcher allegedly tossed his sacred chickens overboard saying “if they will not eat, let them drink!”. The story is regularly used not only to explain how the Romans could possibly have lost but also as a morality tale about the importance of Roman religion and occasionally to illustrate the arrogance of the patricians or this particular gens. The drowning of the sacred chickens appears four times in Cicero, three times in later epitomes of Livy, as well as in Suetonius and Valerius Maximus. If the epitomes of Livy are true to his text, we have to imagine that this is a situation where Livy himself broke from Polybius as his primary source for events. Polybius is our oldest source for the battle, the narrative is complete, and there are no sacred chickens, alive or dead. Cicero never raises the episode in his surviving oratory, only in his philosophical treatises on Religion all composed under the Caesar’s dictatorship. I take from this that the episode was in common currency and ‘good to think with’ but not precisely something one could invoke in a republican political argument. Dionysius likely treated the battle of Drepanum in his late and now largely lost books. I’ve often thought if these survived in full instead of just the earlier more legendary books we might all have a v different option of Dionysius as a historian.

[CUT from actual talk: Dionysius’ only surviving mention of Drepana is a discussion of Aeneas stopping there to build cities for earlier Trojan refugees in book one. Unlike other writers he does not in any way connect the place to the death of Anchises, and he refutes an earlier tradition whereby the city building there was necessitated by women burning ships to end the grueling journey. I detect no foreshadowing of Pulcher’s naval disaster here.]

Slide 16: We do, however, have yet another digression from Dionysius in relationship to Romulus’ state building activities which looks ahead to the disaster at Cannae. While Dionysius is not explicitly engaging with the contemporary here, he is still breaking the fourth wall to again interpret Rome for a Greek audience through comparison with Greek history. Answering in a new way the Polybian question of why did they succeed where we did not. He is also by drawing events far ahead in time than his subject matter, explicitly drawing attention to his own temporal distance from his primary subject and how deep time connects to much latter historical events.

Here Dionysius refutes that the Roman recovery from this disaster had anything to do with Tyche or divine favor (cf. Polybius 1.63.9). Credit instead is given to Romulus’ foresight to keep Roman citizenship open to those deserving of the honor. He attributes the downfall of Sparta, Thebes and Athens to their not having similar means of restoring their manpower. What is missing from this passage is any engagement with why the disaster happened in the first place. Polybius spent the whole of book six outlining the Roman constitution, a project not unlike what Dionysius is undertaking himself in Book 2. For Polybius book six was necessary to explain Rome’s recovery from Cannae: the recovery isn’t about numbers, but about social and military structures, the Roman constitution in the broadest possible sense. Dionysius uses Cannae to highlight the value (and uniqueness) of Rome’s relatively open citizenship, he doesn’t care particularly about the disaster because unlike Crassus’ failures it has not direct resonance on contemporary events, but as a foreign resident at Rome the possibility of accessing Roman citizenship was likely a deeply personal question. Holding up Cannae as a reason for that openness can only aid the delivery of his message to contemporary audiences, and he’s perfectly happy to deny divine agency in this instance.

Slide 17: We’ve had a deep dive into just a little bit of Dionysius, but does any thing we discussed really relate to this conference? And can I justify my original title? Maybe. In my most recent book, I dedicated a half a chapter to the pervasive religious claims Romans make justify their dominion. The nature of the book necessitated a focus on coins, but I opened my discussion with a few passages I considered critical illustrations, the portion of Livy’s preface on Mars, Vergil’s prophecy of Jupiter, and a great bit from Cicero’s Haruspices. Robert Parker in his 2023 Histos article felt a similar impulse to point to to the same pervasive trope and instead chose to use a line from Horace Odes (3.6.5). Parker is not wrong about the power of this quote: “You rule, because you act as second to the Gods”. The use of therm MINOREM to refer to the Romans inherently casts the gods in the role of the MAIORES, the greater ones, or ancestors as we typically translate the Latin term. IMPERAS recalls Imperium and Imperator and the dominion over others that those terms imply. GERO is a verb of action not a state of mind. It is of course the same verb we find at the beginning of Augustus’ account of his things done, the RES GESTAE.

Dionysius without question engages with this trope. Deliberate acts of piety, both divine and filial, are necessary preconditions for Roman success, but I am not sure he holds them to be sufficient, either to explain Rome’s rise to power, i.e. historical causality, or even that he holds these truths as a personal belief system or theology. The questions I want to address as I continue to develop this work in progress is the nature of Dionysius’ Tyche. Is it closer to Roman Fortuna a goddess often more closely associated with divine blessings than chance? Was Parker right to distinguish Tyche in Dionysius from the Gods? And to what extent can we disentangle Dionysius’ individuality from the messaging of the moment?

I hope I’ve given us some food for thought and lively discussion in this work in progress. I look forward to your comments.