Many of you who read my blog know I’ve been planning and scheming to learn more about the interior of aes grave and hopefully say something useful about the ‘value’ of Rome’s first, and arguably most unusual, coins. You might even remember that I won a grant last year. That grant was to use negative muonic x-rays on a few pieces of aes grave excavated from the sanctuary of Diana at Nemi.

This will shock you but I had NO IDEA what I was getting myself into. Well, we’ve done our ‘beam time’ and I’m at Heathrow waiting for a flight to present on iconography at a conference focused on the Sertorian War. I finally have time to reflect on what I’ve just experienced and. it. is. a. lot.

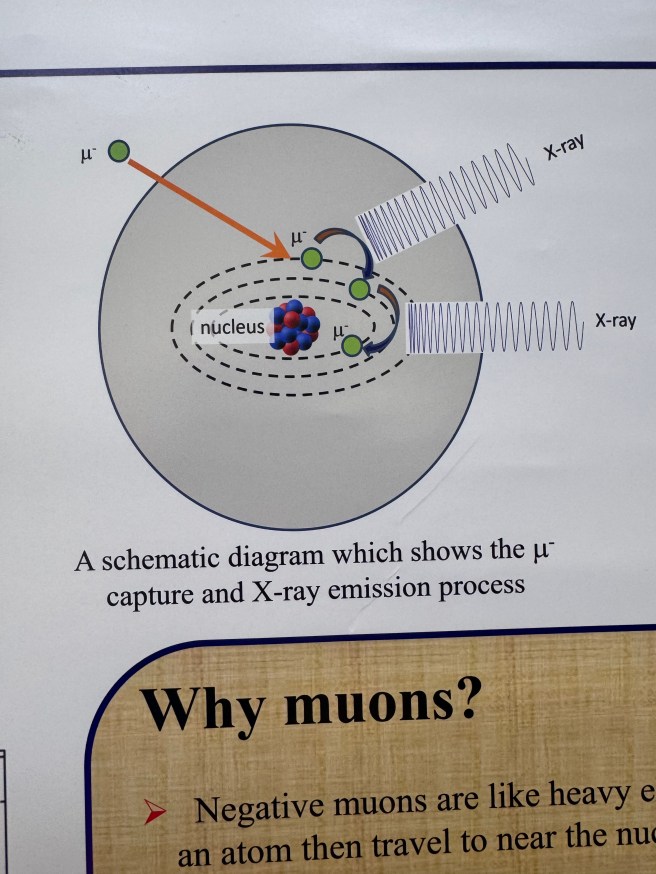

Let’s start with the science and we’ll see if I can explain it a wee bit. Muons are rapidly decaying subatomic particles that can be produced in a particle accelerator. On the beam line the muons come off before the electrons. We then direct these muons towards an object controlling their momentum. That momentum determines how far into the object the muons penetrate. When they penetrate they briefly enter the atoms in the target object.

Imagine an atom. In your mind’s eye you might have a picture a little like a solar system with a sun being the protons in the nucleus and the planets being akin to the electrons. The ‘orbits’ a which the muon can orbit is determined by the nature of the atom itself. They are ‘caught’ extremely briefly in these fixed orbits and then when they decade, we can detect where they were in those atoms and thus what elements are present in the object. Obviously it isn’t one muon and a single decay event, but 100s of thousands that we read using a variety of detectors.

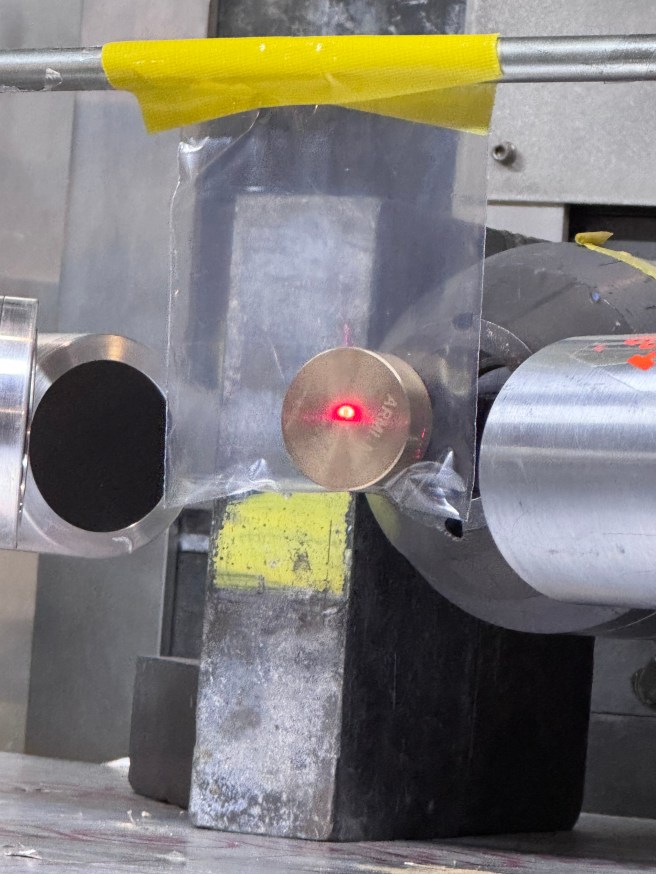

In our experiment we used germanium detectors. No, not the flower, geranium. Germanium, it turns out, is an element. A super sensitive and useful one at that. We had four detectors total. Two more sensitive, two less sensitive. Frankly, I ended up being very fond of the less sensitive as it was easier to understand the preliminary results. These detectors had to be cooled by super conductors. Electrically cooled superconductors can produce minor vibrations, and with muons this is a no no, so we used nitrogen cooled ones.

The whole experimental area where the muons hit the aes grave was tightly controlled with a locking system akin to a nuclear facility, all of which designed to ensure that no one is exposed to unnecessary radiation. Yet, the objects retain no radiation because of the speed of the decay. Super cool and far safer and more specific in the nature of the results form what one could get from neutron activation because we can control depth and targeting.

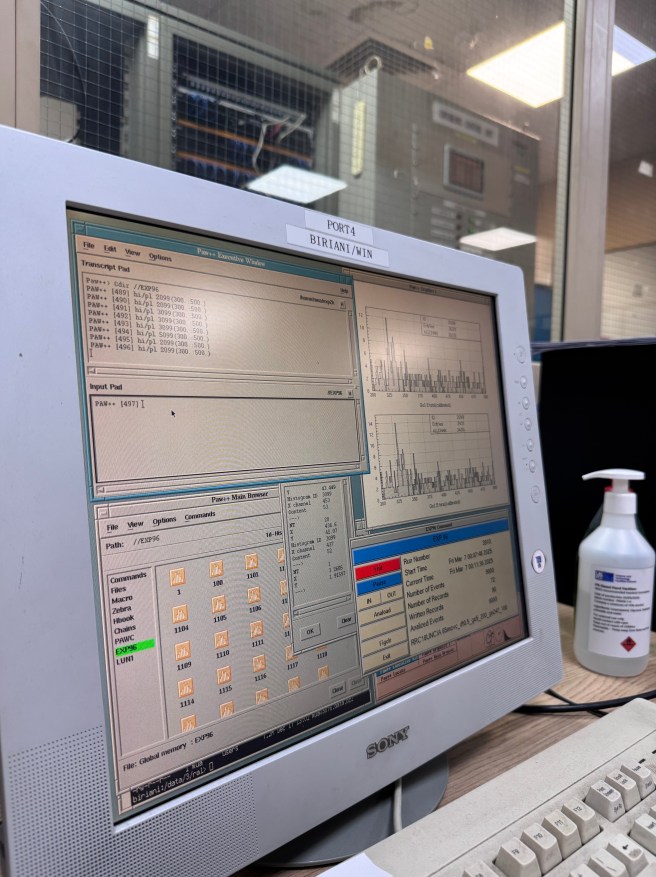

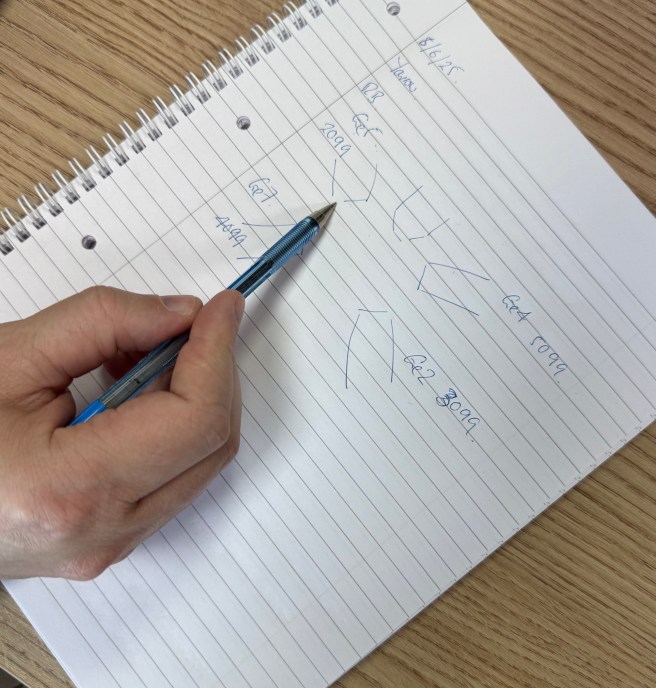

After setting up the experiment, we then monitored and controlled it from a room on the floor above. The key aspects of our work in the control room was setting the momentum and detune (basically weakening) of the beam, setting the solenoid necessary to achieve the momentum, and then monitoring and recording the data. This room had a window on to racks and racks of computer equipment all working at a fever pitch. Next to these racks was the very exciting Solenoid control unit which looked like something out of Star Trek (the original series) and perhaps almost as old. The dial for changing the numbers was analogue and the buttons made that satisfying physical click.

We’d enter our best estimate of the momentum (based on previous modeling) to look at our desired depth within the aes grave and try a detune to help the beam reach that point without overwhelming the germanium sensors. A program would then tell us where to set the solenoid to achieve the momentum and we’d monitor incoming data to see if the detune was sufficient and adjust accordingly.

Yes, I did all of this. Even solo. Sometimes in the wee hours of the night. The experiments run 24-7 as long as the beam is in action. Of course there are hiccups. The beam goes down. The computer systems fail. The cloud cannot be accessed. But overall it worked and we learned SO MUCH.

I’m most shocked I could be trained to do this work and understand something of what I was doing. Like many non-scientists I think of experiments as ‘measurements’. Measurements are what we do with well established methodologies: the ruler, the scale, even a scanning electron microscope. An experiment is taking a new technology and seeing if it can accomplish a new task and studying that process so that one can refine the technology and achieve better, consistent results.

I’m a little embarrassed to say I thought of negative muonic x-rays as a bit of a magic black box for measurement, instead of properly realizing I was partnering with a team led by one of the foremost developers of this technique. These experiments are integral to determining how the technique can be refined and improved. Of course, we got data and I’m excited to share as we clean and analyze, but this is not a simply pXRF. There are only two muonic facilities open to outside users in the world (ISIS in the UK where I was, and another in Japan), there are two more at least one of which will become open to outside users in the new future. The very software to analyze the data we captured was being developed in the same control room by other members of the team.

I’m overawed by this opportunity. It was worth every hour of lost sleep, every scrounging of travel funds, all the stressing over insurance for the objects, the negotiations, the writing, all of it. I saw into a world and a technology that can absolutely transform our collective future in ways far more meaningful than anything I can say about the past. I met brilliant scientists and (over?)dedicated support technologists, all of whom were beyond kind and humble. Frankly I feel I failed to understand the genius at work as I expected it to enter the room proclaiming its own worth rather than reaching out a hand to offer me and my historical questions a little help.

Here are some snapshots. I have lots of explanatory videos but they need editing and stitching into a whole to make a coherent story.