This is a follow up to an old post

Festus says:

Rodus, vel raudus significat rem rudem et inperfectam; nam saxum quoque raudus appellant poetae, ut Accius in Melanippo: “Constit[u]it, cognovit, sensit, conlocat sese in locum celsum; hinc manibus rapere roudus saxeum grande[m] et grave[m]”; et in Chrysippo: “Neque quisquam a telis vacuus, sed uti cuique obviam fuerat, ferrum alius †saxio rudem†.” Vulgus quidem in usu habuit, non modo pro aere inperfec to, ut Lucilius, cum ait: “plumbi pa<u>xillum rodus li nique matexam”; sed etiam signato, quia in manci pando, cum dicitur: “rudusculo libram ferito”, asse tangitur libra. Cincius de verbis priscis sic ait: “Quemadmodum omnis fere materia non deforma ta rudis appellatur, sicut vestimentum rude, non perpolitum; sic aes infectum rudusculum. Apud aedem Apollinis aes conflatum iacuit, id ad rudus appellabant. In aestimatione censoria aes infectum rudus appellatur. Rudiari ab eodem dicuntur, qui saga nova poliunt. Hominem inperi tum rudem dicimus.” Rudentes restes nauticae, et asini, cum voces mittunt.

Working translation:

Rodus, or raudus, signifies an unfinished and imperfect thing; for the poets also call a rock raudus, as Accius in Melanippus:

“He stood, perceived, and recognised; betook And placed himself in a high place; thence seized In hands a huge and heavy unhewn rock.” [this quote is a modified Loeb trans.]

and in Chrysippus:

“Nor was anyone without a weapon, but they came together, some with iron, others with unhewn rock.”

The common people indeed had it in use not only as Lucilius says, for unrefined bronze, as when he says:

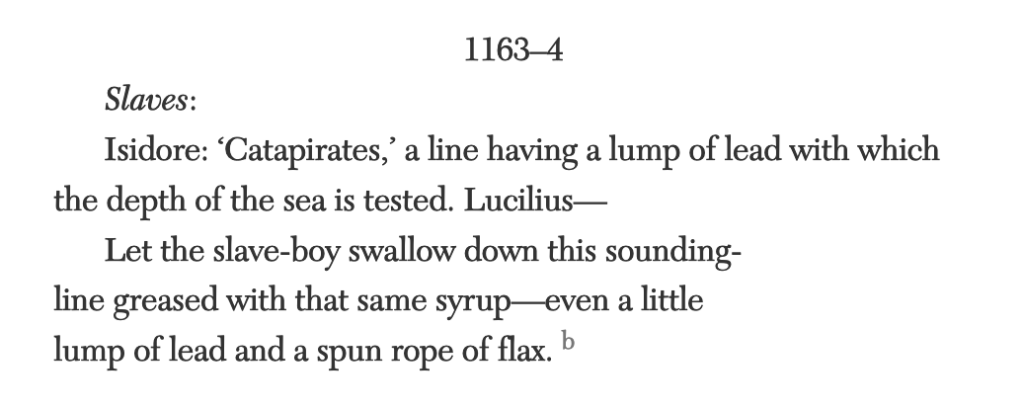

“a little lump of lead and a [fine?] cord [of flax? silk?]” [see below: Isodore also quotes this line with more context]

but also symbolically, in the disposal of property [manumission?!], when it is said: “Let the scale be struck with rudusculo,” as an as touches the scale. [cf. Varro, LL 5.163!]

Cincius says of the ancient words:

“In the same way that almost every material that is not deformed is called rudis, just as a garment is rude, as in not refined; so is unwrought bronze called rudusculum. Near the temple of Apollo was situated fused[?] bronze, which was called rudus. In census appraisals unwrought bronze is called rudus. Rudiari are called thus because they adorn new cloaks. We call an ignorant person, rudem.” [I’ve no idea what the penultimate sentence about rudiari means; I want it to be about rudiarii, i.e. manumitted gladiators, but I just can’t make it work to have that meaning.]

Rudentes [can mean either] the naval ropes, [or] the donkeys when they bellow.

—

Tangential update 1-19-23:

Quote from:

CRAWFORD, Michael H. Thesauri, hoards and votive deposits In: Sanctuaires et sources: Les sources documentaires et leurs limites dans la description des lieux de culte [online]. Naples: Publications du Centre Jean Bérard, 2003 (generated 19 janvier 2023). Available on the Internet: <http://books.openedition.org/pcjb/878>. ISBN: 9782918887218. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pcjb.878.

He translated asses as money but I think given how many actual asses one finds in these things perhaps we should leave it be in the original language.