RRC 372/2 and Roman attitudes at the start of the Sertorian War: A case study of iconographic interpretation for Roman Republican Coinage

In the interests of time I am limiting myself to coinage produced by the Romans and will focus on a close reading of a single coin to demonstrate my approach this type of analyses. I’m exceptionally grateful to the generosity of organizers. I only wish I could have heard more papers. | RRC 372/2 y las actitudes romanas al inicio de la Guerra Sertoriana: Un estudio de caso de interpretación iconográfica para la moneda republicana romana

En interés del tiempo, me limito a la moneda emitida por los romanos y me concentraré en una lectura detallada de una sola moneda para demostrar mi enfoque en este tipo de análisis. Estoy excepcionalmente agradecido por la generosidad de los organizadores. Solo desearía haber podido escuchar más ponencias. |

How to access supplementary materials

If you are reading this, you have successfully accessed these materials. | Cómo acceder a los materiales suplementarios

Si estás leyendo esto, has accedido con éxito a estos materiales. |

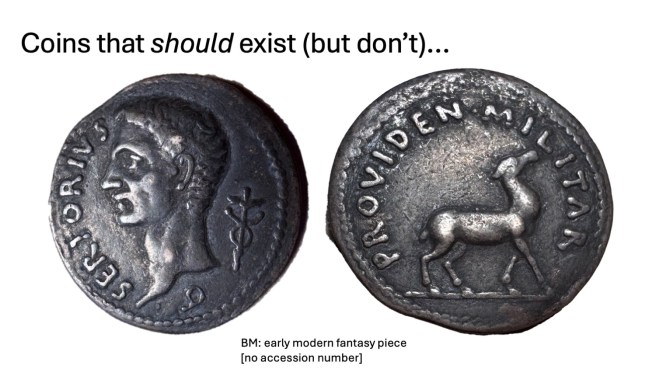

Coins that should exist (but don’t)

Both today and in early modern era there has been a great urge to connect our surviving texts with our surviving images, but we must allow for all we have lost and all we have yet to learn. I show an early modern ‘fantasy’ coin made for collectors who wanted a more ‘complete’ series of Roman republican coin. Similar fakes for other famous Romans also exist including Scipio and Cataline among others. | Monedas que deberían existir (pero no existen)

Tanto hoy como en la era moderna temprana ha existido una gran urgencia por conectar nuestros textos supervivientes con nuestras imágenes sobrevivientes, pero debemos permitirnos aceptar todo lo que hemos perdido y todo lo que aún debemos aprender. Muestra una “fantasía” de la moneda moderna temprana hecha para coleccionistas que querían una serie más “completa” de monedas republicanas romanas. También existen falsificaciones similares de otros romanos famosos, incluidos Escipión y Catilina, entre otros. |

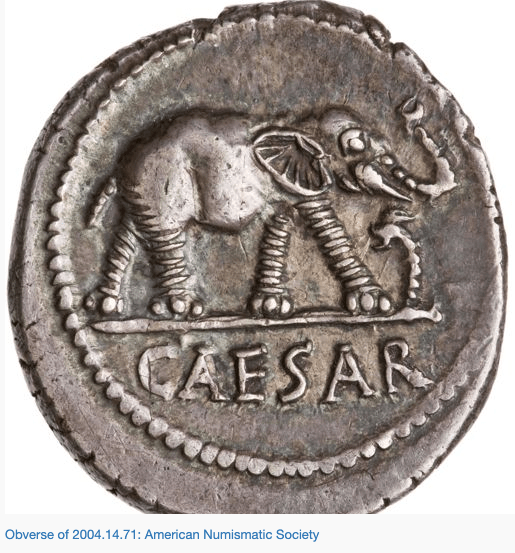

| ”Roman” coins connected to the Sertorian War Arguably these are the three most important types created in reaction to the Sertorian War. I am discussing only one today, the only regular issue of the Roman mint itself, but wish to discuss all three in a final publication. The aureus has been well studied by Woytek and I concur with his hypothesis it was struck in Spain: metallurgical testing is need to confirm. | Monedas “romanas” relacionadas con la Guerra Sertoriana

Argumentablemente, estos son los tres tipos más importantes creados en reacción a la Guerra Sertoriana. Hoy solo estoy discutiendo uno, el único emitido regularmente por la propia casa de la moneda romana, pero deseo discutir los tres en una publicación final. El aureus ha sido bien estudiado por Woytek y concuerdo con su hipótesis de que fue acuñado en España: se necesita una prueba metalúrgica para confirmarlo. |

| The uniqueness of the later RR denarius series For the first half century of its existence the denarius was as conservative in its design as most other Mediterranean mints. After the long period of continuity, we then see rapid evolving design change. The narration of this evolution cannot be covered in detail today, but I provide a supplemental one page overview with the most relevant points. Notice that moneyers can leave off any reference at all to Rome in both design and legend. Typically this is how both we and the ancients attribute a coin to its issuing authority: What makes a Roman coin identifiable as a Roman coin? | La singularidad de la serie posterior de denarios RR

Durante el primer medio siglo de su existencia, el denario fue tan conservador en su diseño como la mayoría de las casas de moneda del Mediterráneo. Después de este largo periodo de continuidad, vemos un rápido cambio evolutivo en el diseño. La narración de esta evolución no puede abordarse en detalle hoy, pero proporciono una visión general suplementaria en una página con los puntos más relevantes. Observa que los monetarios pueden omitir cualquier referencia a Roma tanto en el diseño como en la leyenda. Típicamente, así es como tanto nosotros como los antiguos atribuimos una moneda a su autoridad emisora: ¿qué hace identificable a una moneda romana como una moneda romana? |

| How can we explain the change? Crawford and others suggested this design change was about elite competition, perhaps exacerbated by the introduction of the secret ballot. I argue that it is Mediterranean wide hegemony that leads to the instant recognizability of the denarius and allows for more diverse design choices. | ¿Cómo podemos explicar el cambio?

Crawford y otros sugirieron que este cambio de diseño se debía a la competencia entre las élites, quizás exacerbada por la introducción del voto secreto. Yo argumento que es la hegemonía en todo el Mediterráneo lo que lleva al reconocimiento instantáneo del denario y permite elecciones de diseño más diversas. |

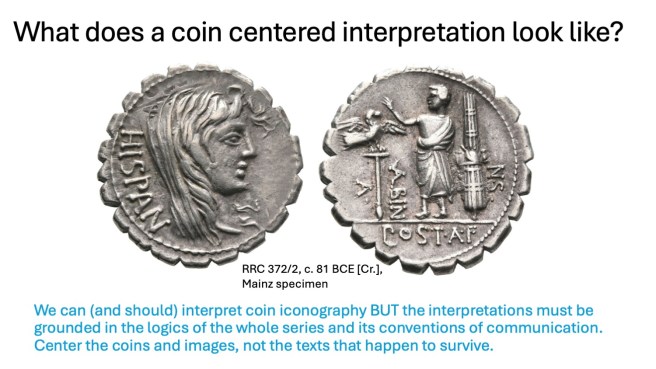

| What does a coin centered interpretation look like? My primary goal today is to suggest ways to read a coin in relationship to other coins and material culture, decentering direct connections to our literary texts. What follows is a demonstration of my general approach to the material. It centers both what moneyer and audiences would have had as context for interpreting the imagery. | ¿Cómo se ve una interpretación centrada en la moneda?

Mi objetivo principal hoy es sugerir formas de leer una moneda en relación con otras monedas y la cultura material, descentrando las conexiones directas con nuestros textos literarios. Lo que sigue es una demostración de mi enfoque general hacia el material. Se centra tanto en lo que el monetario como las audiencias habrían tenido como contexto para interpretar las imágenes. |

| Crawford’s interpretation When trying to understand Roman republican coin imagery, most of us, myself included, start by consulting Crawford’s 1974 type catalogue. He assumed an understanding of the design of this coin should be sought in the family history of the moneyer rather than any direct contemporary significance. Yet the instance he suggests it may commemorate seems lacking glory at least as reported by Livy. Of course, anumber of Roman republican coin types lie about ancestral relationships and inflate accomplishments. And, we don’t know the precise genealogy of the moneyer or the family in general. Crawford suggests the reverse may be a statement on the balance between civic and military power. | La interpretación de Crawford

Cuando tratamos de entender las imágenes de las monedas republicanas romanas, la mayoría de nosotros, incluyéndome, comenzamos consultando el catálogo de tipos de Crawford de 1974. Él asumió que el entendimiento del diseño de esta moneda debería buscarse en la historia familiar del monetario, más que en cualquier significancia contemporánea directa. Sin embargo, el caso que sugiere que podría conmemorar parece carecer de gloria, al menos según lo reportado por Tito Livio. Claro, varios tipos de monedas republicanas romanas mienten sobre relaciones ancestrales y exageran logros. Y no sabemos la genealogía precisa del monetario ni de la familia en general. Crawford sugiere que el reverso puede ser una declaración sobre el equilibrio entre el poder cívico y militar. |

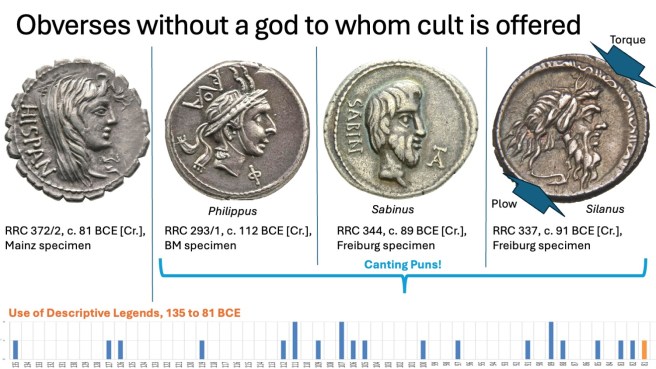

| Obverses without a god to whom cult is offered Hispania is very unique choice for a number of reasons. This is only the fourth time at the Roman mint where the obverse is not a god actively worshipped by the Romans. All three of the earlier examples are canting puns on the moneyers’ names. Moreover, descriptive legends, rather than legends that indicate the issuing authority (ROMA) or moneyer or denomination, are also relatively new and infrequent. The moneyer is clearly invested in our knowing who this woman is. | Anversos sin un dios a quien se ofrezca culto

Hispania es una elección muy única por varias razones. Esta es solo la cuarta vez en la casa de la moneda romana en la que el anverso no es un dios activamente venerado por los romanos. Los tres ejemplos anteriores son juegos de palabras cantantes con los nombres de los monetarios. Además, las leyendas descriptivas, en lugar de leyendas que indiquen la autoridad emisora (ROMA), el monetario o la denominación, también son relativamente nuevas e infrecuentes. El monetario está claramente interesado en que sepamos quién es esta mujer. |

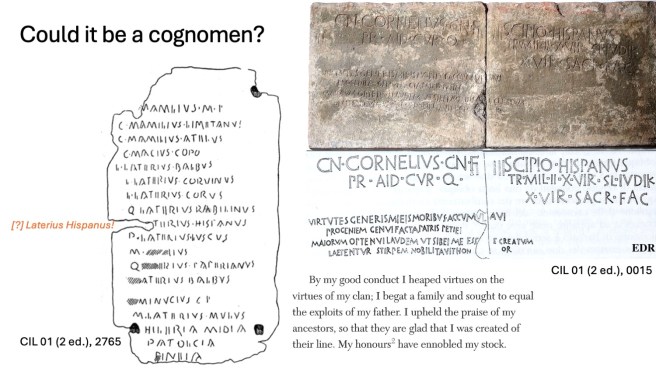

| Could it be a cognomen? Cognomina being with Hispan- are well attested, most famously among the Cornelii Scipiones, but also by sub elite families, hence my inclusion of a defixio dating probably for the decades just proceeding this coin. It is possible the obverse is evidence of a cognomen, but we have no supporting evidence of its use in the moneyer’s patrician gens and I don’t consider it particularly probable. | ¿Podría ser un cognomen?

Los cognomina que comienzan con Hispan- están bien atestiguados, más famoso entre los Cornelii Scipiones, pero también por familias subélite, de ahí mi inclusión de una defixio que probablemente data de las décadas anteriores a esta moneda. Es posible que el anverso sea evidencia de un cognomen, pero no tenemos pruebas de su uso en la gens patricia del monetario y no lo considero particularmente probable. |

| How (and why) are provincia are represented? This is the very first personification of a Roman province on a coin. This type of representation will become ubiquitous in the Empire, in coins and any number of other media. Of course, this numismatic representation in 81 BCE may have had precedents in other now lost media. However, prior coins used symbols, primarily distinctive enemy arms, to represent provincial, i.e. the work of those with imperium. Here we see a peaceable representation, much closer to later depictions of provinces as bountiful dependents of the Roman empire. This design likely directly influenced the choice of Pompey in the obverse design of his aureus with the head of Africa struck some time in the next decade. | ¿Cómo (y por qué) se representan las provincias?

Esta es la primera personificación de una provincia romana en una moneda. Este tipo de representación se volverá ubicuo en el Imperio, en monedas y en otros medios. Por supuesto, esta representación numismática en el 81 a.C. pudo haber tenido precedentes en otros medios ahora perdidos. Sin embargo, las monedas anteriores usaban símbolos, principalmente armas distintivas de los enemigos, para representar las provincias, es decir, el trabajo de aquellos con imperium. Aquí vemos una representación pacífica, mucho más cercana a las representaciones posteriores de las provincias como dependencias abundantes del Imperio romano. Este diseño probablemente influyó directamente en la elección de Pompeyo para el diseño del anverso de su aureus con la cabeza de África, acuñado en la siguiente década. |

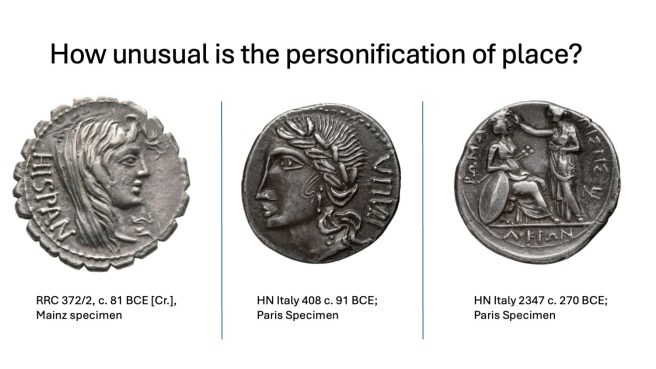

| How unusual is the personification of place? We have plenty of earlier examples of the personification of places on coins. Italia on the Social War coinage is the collective spirit of those allied against Rome. It is the first time such a collective identity under this name is conceived. Of course it echoes the personification of Roma herself on Roman coins. The Locrian coin shows Roma crowned by Pistis (fides) almost two centuries before our Hispania coin. I include it to show that foreign places can and did also appear on coins in Italy before this point. | ¿Qué tan inusual es la personificación de un lugar?

Tenemos muchos ejemplos anteriores de la personificación de lugares en monedas. Italia en la moneda de la Guerra Social es el espíritu colectivo de aquellos aliados contra Roma. Es la primera vez que se concibe una identidad colectiva bajo este nombre. Por supuesto, hace eco de la personificación de Roma misma en las monedas romanas. La moneda de Locri muestra a Roma coronada por Pistis (fides) casi dos siglos antes de nuestra moneda de Hispania. La incluyo para mostrar que los lugares extranjeros también podían aparecer en las monedas en Italia antes de este punto. |

| Personifications of ”Foreign” Places The so called Darius vase was created in Southern Italy is a little earlier than the Locrian coin and shows both Hellas and Asia as characters in the narration of the Persian wars. | Personificaciones de “Lugares Extranjeros”

El llamado jarrón de Darío, creado en el sur de Italia, es un poco anterior a la moneda de Locri y muestra tanto a Hellas como a Asia como personajes en la narración de las guerras persas. |

| Wider Hellenistic Symbolic System Both the use of enemy arms and female personifications of political bodies are well attested in wider Hellenistic iconography. Rome as in so many other cases is here developing upon a well-established wider Mediterranean phenomenon. Here I juxtapose Roma adorning a Gallic trophy with Aetolia seated on a pile of Macedonian and Gallic arms. | Sistema simbólico helenístico más amplio

Tanto el uso de armas enemigas como las personificaciones femeninas de cuerpos políticos están bien atestiguados en la iconografía helenística más amplia. Roma, como en tantos otros casos, está desarrollando aquí un fenómeno bien establecido en todo el Mediterráneo. Aquí yuxtapongo a Roma adornando un trofeo galo con Aetolia sentada sobre un montón de armas macedonias y galas. |

| equites Hispanos I would argue that this change in the representation of Hispania is a strong indication of Rome’s idealized view its relationship with the peninsula. Hispania is ultimately part of the Roman empire, perhaps as much as Italy itself. In the immediately preceding conflict, Spanish soldiers had proved themselves more loyal than even some Italians, integration into the citizen body was the logical reward in the Roman mind. Again, I point to how the offers of citizenship to indigenous populations in Iberia arose in the discussion following the first session this morning. | Equites Hispanos

Yo argumentaría que este cambio en la representación de Hispania es una fuerte indicación de la visión idealizada de Roma sobre su relación con la península. Hispania es, en última instancia, parte del Imperio romano, quizás tanto como Italia misma. En el conflicto inmediatamente anterior, los soldados españoles demostraron ser más leales que incluso algunos italianos, la integración en el cuerpo de ciudadanos era el lógico premio en la mente romana. Una vez más, hago hincapié en cómo surgieron las ofertas de ciudadanía para las poblaciones indígenas en Iberia durante la discusión posterior a la primera sesión de esta mañana. |

| Peaceable and Prosperous This view of the peninsula, I think is critical context for how the Romans approach the Sertorian conflict and even how it is remembered in our sources. As the Roman republican coin series develops personification of places split into the downtrodden and defeated, Sicily and Gaul are foremost examples, Hispania here is closer to Italia and Alexandria. The peacable and prosperous provinces are not Rome’s equal but integral to her stable mediterranean Dominion. The story of the late republic is one of a shift from Rome asserting control through treaties of mutual obligation to a system of direct rule and political limited integration. While this wasn’t reality in 81 BCE, we’re seeing an expression of this Roman ideal expressed on the coinage. | Pacífica y próspera

Esta visión de la península, creo, es un contexto crítico para cómo los romanos abordan el conflicto sertoriano e incluso cómo se recuerda en nuestras fuentes. A medida que se desarrolla la serie de monedas republicanas romanas, la personificación de los lugares se divide en los oprimidos y derrotados, Sicilia y la Galia son ejemplos prominentes, mientras que Hispania aquí está más cerca de Italia y Alejandría. Las provincias pacíficas y prósperas no son iguales a Roma, pero sí parte integral de su dominio mediterráneo estable. La historia de la última república es una de un cambio desde que Roma afirmaba el control mediante tratados de obligación mutua hacia un sistema de gobierno directo e integración política limitada. Aunque esto no era una realidad en el 81 a.C., estamos viendo una expresión de este ideal romano expresado en la moneda. |

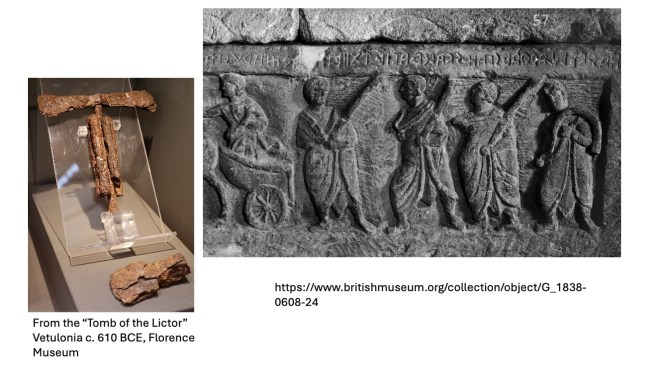

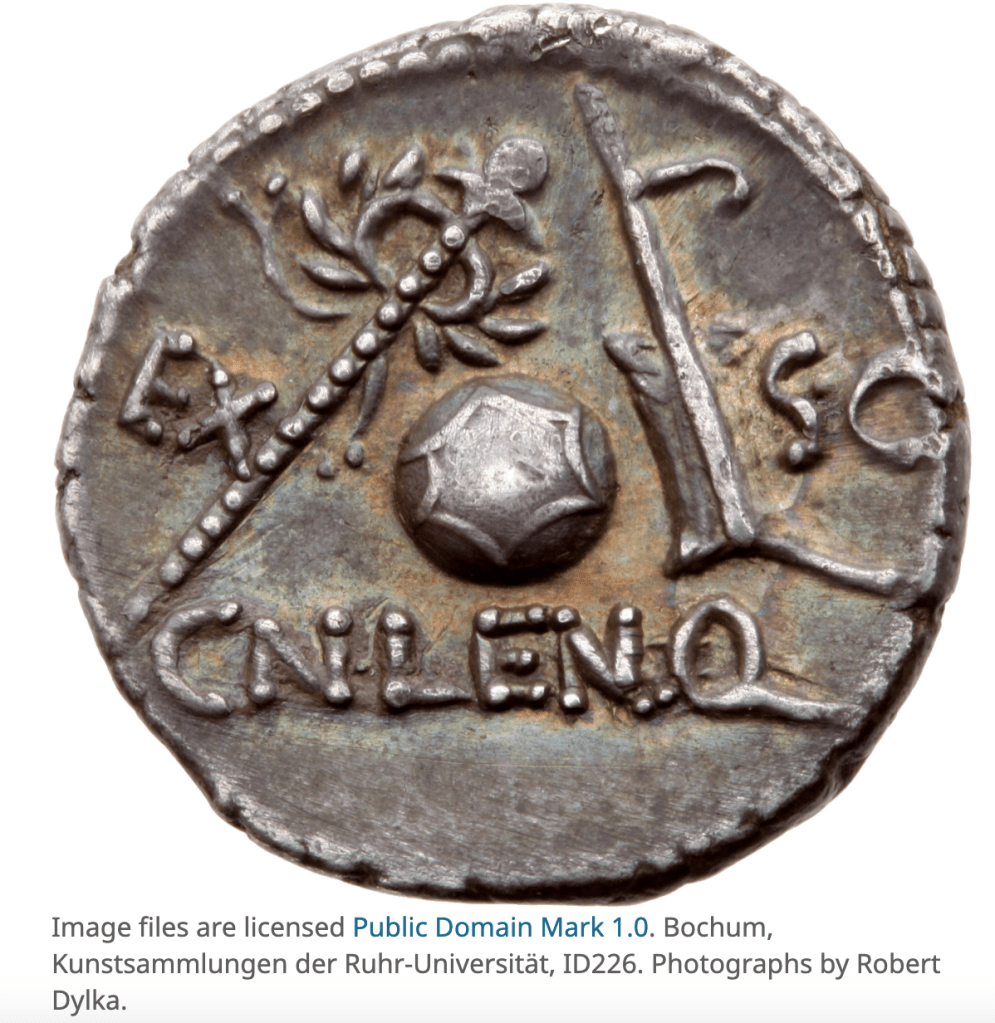

| First representations of Standards & Fasces (83-81 BCE!) The reverse is nearly equally innovative. It combines the Aquila and the Fasces as symbolic elements. The only precedents are two issues from the immediately preceding two years and the clashes between Sulla and the Cinnan faction. With our coin,as the Roman mint returns to more normal production by ordinary moneyers, both symbols are combined into a single design. Notice that these fasces have axes and thus represent military imperium, not civic. | Primeras representaciones de Estandartes y Fasces (¡83-81 a.C.!)

El reverso es igualmente innovador. Combina el Áquila y los Fasces como elementos simbólicos. Los únicos precedentes son dos emisiones de los dos años inmediatamente anteriores y los choques entre Sila y la facción de los Cinna. Con nuestra moneda, mientras la casa de la moneda romana vuelve a una producción más normal por monetarios ordinarios, ambos símbolos se combinan en un solo diseño. Observa que estos fasces tienen ejes y, por lo tanto, representan el imperium militar, no cívico. |

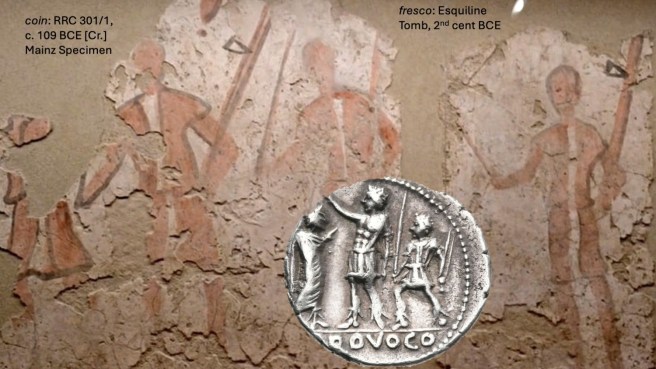

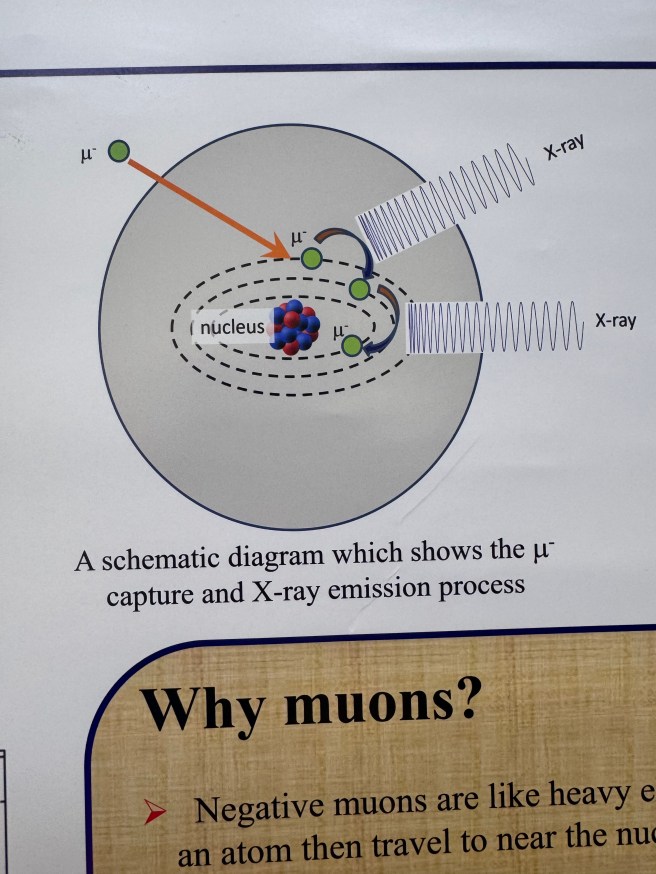

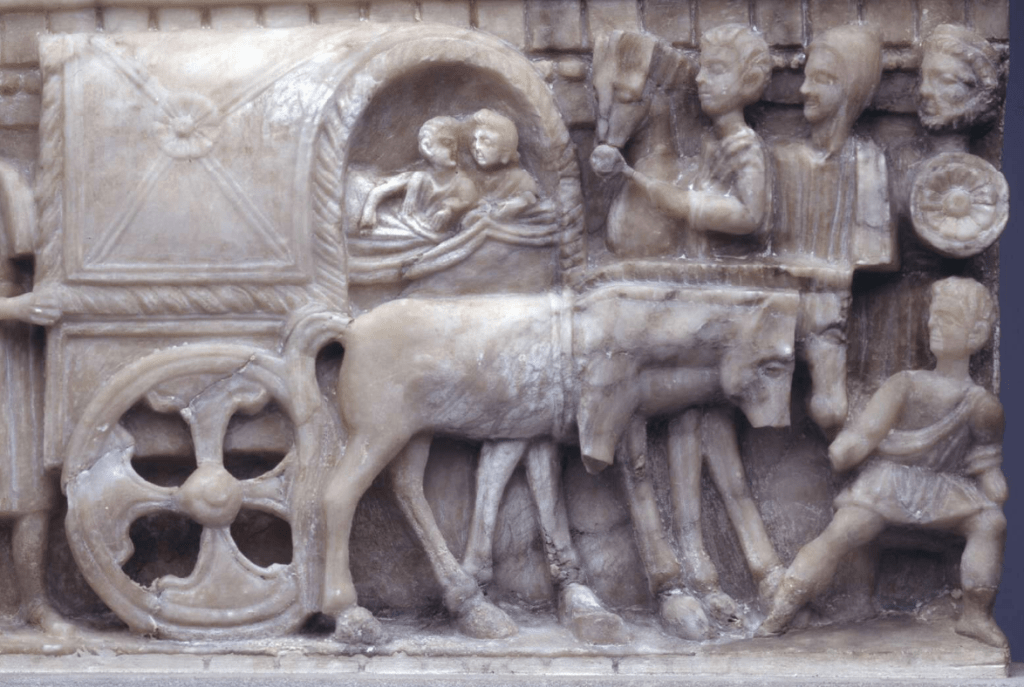

| [no slide title] Second century BCE representations of fasces, arguably the earliest we have from Rome, emphasis the use of the fasces by lictors rather than the tool as a stand alone symbol of imperium. | [sin título de diapositiva] Las representaciones de los fasces del siglo II a.C., probablemente las más antiguas que tenemos de Roma, enfatizan el uso de los fasces por los lictores en lugar de la herramienta como un símbolo independiente del imperium. |

| [no slide title] Earlier precedents for standards in Roman art are hard to establish for all we seem to have some similar military banners depicted in Lucanian tomb painting. I’m not positive the little symbols in the top left of the left hand coin are really standards as identified by Crawford and others, but I have no better explanation of the type. More interesting to my mind is the use of a standard on a cistophoric coinage by the Cinnan commander and mutineer Fimbria in Asia Minor just 5 years earlier. Combined with the coins on the last slide it is suggestive a strong interest in symbols of power in this moment of intense civil strife. | [sin título de diapositiva] Es difícil establecer precedentes anteriores para los estandartes en el arte romano, aunque parece que tenemos algunos estandartes militares similares representados en las pinturas de tumbas lucanas. No estoy seguro de que los pequeños símbolos en la parte superior izquierda de la moneda de la izquierda sean realmente estandartes como los identificados por Crawford y otros, pero no tengo una mejor explicación del tipo. Más interesante para mí es el uso de un estandarte en una moneda cistofórica emitida por el comandante cínnano y amotinador Fimbria en Asia Menor solo cinco años antes. Combinado con las monedas en la última diapositiva, sugiere un fuerte interés en los símbolos de poder en este momento de intenso conflicto civil. |

| [no slide title] Stray passages from Sallust, Cicero, and Pliny all point to a growing importance of the Aquila as evolving and powerful political symbol in this period. In these passages Marius is closely associated with the Aquila and Catiline is said to have drawn on this memory to motivate his own followers. The combination of fasces axes and aquila is found in the bottom passage from Cicero. And the same combination is recorded in Appian in relation to Sulla’s funerary honors. I would not suggest that the iconography on our coin is partisan, although it is logical to suggest the moneyer and designs were acceptable to Sulla as dictator now in control of the city. Rather I take from the literary passage confirmation of my interpretation of the importance of symbolic displaces in this period of Roman history. | [sin título de diapositiva] Pasajes dispersos de Sallustio, Cicerón y Plinio apuntan a una creciente importancia del Áquila como un símbolo político en evolución y poderoso en este período. En estos pasajes, Mario está estrechamente asociado con el Áquila y se dice que Catilina utilizó este recuerdo para motivar a sus propios seguidores. La combinación de los fasces, los ejes y el Áquila se encuentra en el pasaje inferior de Cicerón. Y la misma combinación se registra en Apiano en relación con los honores funerarios de Sila. No sugeriría que la iconografía en nuestra moneda sea partidista, aunque es lógico sugerir que el monetario y los diseños eran aceptables para Sila como dictador ahora en control de la ciudad. Más bien, tomo del pasaje literario la confirmación de mi interpretación sobre la importancia de los desplazamientos simbólicos en este período de la historia romana. |

| [no slide title] I was particularly struck this morning by how the first paper this morning drew out how important the symbolism of the fasces was in the political self fashioning of the Sertorians both in Asia (thanks to Plutarch’s testimony) and in Iberia with the sling bullets. I agree with their suggestion that a framing of the conflict an extension of the factional Roman struggles was a more benefitial to the Romans than acknowledging the agency of foriegn powers that could establish independence from Imperium. Something we also saw in the discussion of the application of the label ‘pirate’ by one side on the other. | [sin título de diapositiva]

Esta mañana me sorprendió especialmente cómo el artículo de Gerard y Elena también destacó lo importante que era el simbolismo de los fasces en la autoformación política de los Sertorianos, tanto en Asia (gracias al testimonio de Plutarco) como en Iberia con las balas de honda. Estoy de acuerdo con su sugerencia de que enmarcar el conflicto como una extensión de las luchas faccionales romanas fue más beneficioso para los romanos que reconocer la agencia de poderes extranjeros que podrían establecer independencia del Imperium. |

| Earlier Togate figures The key attribute of the central figure is his toga. Earlier numismatic depictions of togate figures show individuals engaged in religious or civic actions. The civic actions tend to be non specific ‘every man’ images whereas the religious represent specific individuals, namely ancestors of the moneyers. Neither category seems to fit our coin well. | Figuras togas anteriores

El atributo clave de la figura central es su toga. Las representaciones numismáticas anteriores de figuras con toga muestran individuos involucrados en acciones religiosas o cívicas. Las acciones cívicas tienden a ser imágenes no específicas de “hombre común”, mientras que las religiosas representan individuos específicos, es decir, los ancestros de los monetarios. Ninguna de las dos categorías parece ajustarse bien a nuestra moneda. |

| Depictions of Ancestors The majority of ancestors on earlier coins are engaged in military heroics. In these representations the ancestors are dressed as soldiers not in the toga. In only about half the instances are we confident we know which specific ancestor is being honored, and thus we should not be surprised we are unsure about the figure on our own coin. | Representaciones de Ancestros

La mayoría de los ancestros en las monedas anteriores están involucrados en heroicidades militares. En estas representaciones, los ancestros están vestidos como soldados, no con toga. En solo la mitad de los casos estamos seguros de saber qué ancestro específico se está honrando, por lo que no deberíamos sorprendernos de que estemos inseguros sobre la figura en nuestra propia moneda. |

| Our knowledge isn’t static Likewise, we need to remain open to new interpretations. The coin on the bottom here was attributed to a victory in by a Memmius in Macedonia by Crawford and few have taken note that this interpretation has been corrected by epigraphical finds in Spain. New data will continue to emerge and we’ll be better able to incorporate it if we refrain from certitude based primarily on literary connections. | Nuestro conocimiento no es estático

Del mismo modo, necesitamos seguir abiertos a nuevas interpretaciones. La moneda que aparece aquí en la parte inferior fue atribuida por Crawford a una victoria de un Memmius en Macedonia, y pocos han notado que esta interpretación ha sido corregida por hallazgos epigráficos en España. Continuarán surgiendo nuevos datos y seremos mejores para incorporarlos si evitamos la certidumbre basada principalmente en conexiones literarias. |

| So many Sp. Postumii! While we have many famous and obscure Auli and Spurii Postumii, none have a known connection with any of the provinciae of the Iberian Pennisula. Crawford selected a Lucius Postumius to make a connection to our literary texts. Yet this coin is the very first time a grandfather’s praenomen is included as part of the moneyer’s name on any coin. Given that the N. S. is in the field it seems likely that this may be a clue to the identity of the togate figure, if not the grandfather himself. For context, notice that even filiations are far from standard on the republican coin series, first appearing only in 149 BCE with only sporadic usage thereafter. | ¡Tantos Sp. Postumii!

Aunque tenemos muchos Aulos y Espurios Postumios famosos y desconocidos, ninguno tiene una conexión conocida con alguna de las provincias de la Península Ibérica. Crawford seleccionó a un Lucio Postumio para hacer una conexión con nuestros textos literarios. Sin embargo, esta moneda es la primera vez que el praenomen de un abuelo se incluye como parte del nombre del monetario en cualquier moneda. Dado que la N. S. está en el campo, parece probable que esto pueda ser una pista de la identidad de la figura con toga, si no del abuelo mismo. Como contexto, notemos que incluso las filiaciones están lejos de ser estándar en la serie de monedas republicanas, apareciendo por primera vez solo en el 149 a.C. y con un uso esporádico después de eso. |

| Living Romans?! I think it is unlikely our coin is meant to represent the moneyer or another living Roman given the lack of good parallels or clear labels, but given that we have earlier examples of living Romans on the reverse of coins often in togas the possibility had to be briefly considered. All except the top right coin were struck by the individuals whom they portray. | ¿Romanos vivos?

Creo que es poco probable que nuestra moneda esté destinada a representar al monetario o a otro romano vivo, dada la falta de buenos paralelismos o etiquetas claras, pero dado que tenemos ejemplos anteriores de romanos vivos en el reverso de las monedas, a menudo con toga, se tuvo que considerar brevemente esta posibilidad. Todas las monedas, excepto la de la parte superior derecha, fueron acuñadas por las personas a las que representan. |

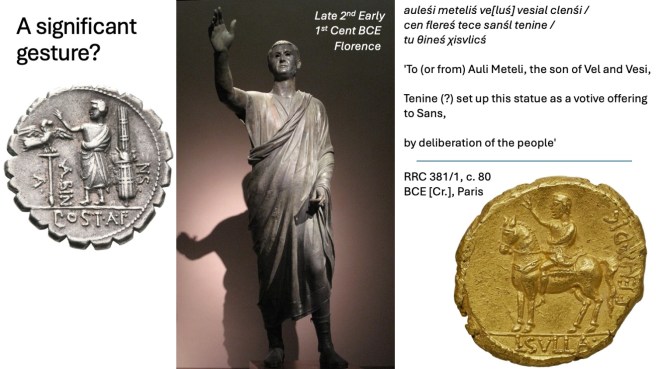

| A significant gesture? The final clue is the gesture of the togate figure. Our figure raises his arm in a manner reminiscent of the only slightly earlier Etruscan statue of Auli Meteli, often called the “Orator”. AND, perhaps more significantly, like the portrayal of Sulla’s equestrian statue on the nearly contemporary aureus. You can see by the head shape, hair and rendering of the toga, these two designs may even have been engraved by the same hand. It is hard for me to imagine the standing figure is meant to be Sulla himself, but it may be meant to recall a statue in Rome of one of the moneyer’s ancestors. | ¿Un gesto significativo?

La última pista es el gesto de la figura con toga. Nuestra figura levanta su brazo de una manera que recuerda a la estatua etrusca ligeramente anterior de Aulo Metelio, a menudo llamada el “Orador”. Y, quizás más significativamente, como la representación de la estatua ecuestre de Sila en el aureus casi contemporáneo. Se puede ver por la forma de la cabeza, el cabello y la representación de la toga, que estos dos diseños pueden incluso haber sido grabados por la misma mano. Me cuesta imaginar que la figura de pie está destinada a ser el propio Sila, pero podría estar destinada a recordar una estatua en Roma de uno de los ancestros del monetario. |

| A significant gesture! This gesture is also a distinctive element in adlocutio scenes on imperial coins and across similar scenes in imperial art, including the famous Prima Porta statue of Augustus. While in late Roman art the emperor often addresses the troops in armor, in the Julio-Claudian period these scenes almost exclusively have the emperor in a toga. We also see the emperor in a toga addressing the troops on the arch of Trajan and the arch of Marcus Aurelius. In these adlocutio scenes the troops being addressed are typically holding Aquilae and standards. Notice on our coin how the togate figure seems to speak towards the aquila. It seems likely we see here is a republican precedent for the familiar and repeating imperial set scene. | ¿Un gesto significativo?

Este gesto también es un elemento distintivo en las escenas de adlocutio en las monedas imperiales y en escenas similares en el arte imperial, incluida la famosa estatua de Augusto de la Prima Porta. Mientras que en el arte romano tardío el emperador suele dirigirse a las tropas con armadura, en el período Julio-Claudiano estas escenas casi exclusivamente muestran al emperador con toga. También vemos al emperador con toga dirigiéndose a las tropas en el arco de Trajano y el arco de Marco Aurelio. En estas escenas de adlocutio, las tropas a las que se dirige suelen estar sosteniendo Áquilas y estandartes. Notemos en nuestra moneda cómo la figura con toga parece hablar hacia el Áquila. Parece probable que aquí estemos viendo un precedente republicano para la familiar y repetida escena imperial. |

| A connection with the Sertorian War In 81 BCE the major miliary threat to Rome was in Hispania and Sertorius’ combined Spanish and Roman forces. Yet, at Rome, Hispania is imagined as a peaceable province. There is a minimization of the threat of any independence or fracturing. For all we cannot know for certain who is intended as the central figure on the reverse, nevertheless it emphasizes the relationship of the troops to those invested with imperium by the Roman people. The aquila become a synecdoche for the troops as a collective body. A Roman commander has a special relationship to his soldiers created not only though his personal bravery, but also through his ability to communicate, inspire, and direct coherent group action. The reverse communicates the importance of the proper order of things. Sertorius threatened that order and needed to be de legitimized and minimized, both by celebrating the idealized relationship of Hispania to Rome and the ideal relationship of a commander with imperium to his troops. In many ways this coin foreshadows the imperial art and ideals of the principate. If time had allowed, I would have liked to also draw in comparisons of the same moneyer’s other issue with Diana and a scene of sacrifice, but I’ve already shared perhaps more than I should. Thank you for your attention and I’m happy to take questions. | Una conexión con la guerra sertoriana

En el 81 a.C., la principal amenaza militar para Roma estaba en Hispania y las fuerzas combinadas de Sertorio de españoles y romanos. Sin embargo, en Roma, Hispania es imaginada como una provincia pacífica. Hay una minimización de la amenaza de cualquier independencia o fractura. Aunque no podemos saber con certeza quién está representado como la figura central en el reverso, sin embargo, enfatiza la relación de las tropas con aquellos investidos con el imperium por el pueblo romano. El Áquila se convierte en una metonimia para las tropas como un cuerpo colectivo. Un comandante romano tiene una relación especial con sus soldados creada no solo por su valentía personal, sino también por su capacidad para comunicarse, inspirar y dirigir una acción grupal coherente. El reverso comunica la importancia del orden adecuado de las cosas. Sertorio amenazaba ese orden y necesitaba ser deslegitimado y minimizado, tanto celebrando la relación idealizada de Hispania con Roma como la relación ideal de un comandante con imperium con sus tropas. De muchas maneras, esta moneda anticipa el arte imperial y los ideales del principado. Si el tiempo lo hubiera permitido, también me habría gustado hacer comparaciones con la otra emisión del mismo monetario con Diana y una escena de sacrificio, pero ya he compartido quizás más de lo que debería. Gracias por su atención y estoy feliz de responder preguntas. |