So I don’t think I’ve ever thought particularly hard about this uncia type although the types of RRC 39 are exceptionally fascinating as a group (see my previous comments on the semiuncia). I ended up here because I was trying to better understand the context of a passage in Dionysius today:

Yet this village [sc. Pallatium, Evander’s foundation,] was ordained by fate to excel in the course of time all other cities, whether Greek or barbarian, not only in its size, but also in the majesty of its empire and in every other form of prosperity, and to be celebrated above them all as long as mortality shall endure. (D. H. 1.31.3)

So this seems related to the idea of Rome as the Eternal City, but I realized I knew next to nothing about the origins of this concept. Turns out its right in Dionysius’ own day with the earliest Latin articulation being Tibullus (c.55-19BC):

Romulus aeternae nondum formaverat urbis (Elegies 2.5.23)

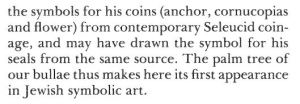

This brought me to a survey article written in 1965 that included this intriguing paragraph on the iconography of aeternitas (p. 29):

I’m not endorsing (yet) this interpretation of the type, but it a sharp observation and a intriguing possibility I’d like to think about another day when I have more time! From a numismatic perspective one would have to also consider in this context all the other republican issues which juxtapose the sun and the moon: RRC 309/1, 310/1, 390/1, 474/5, and 494/20b.

Update on 10/11/15:

Dionysius’ reception of the concept of Rome as the Eternal City is some what problematized by his version of the Marcus Curtius story as preserved in the fragmentary books (14.11). He says Curtius had to throw himself into the gap to give Rome more strong young men. Livy’s version instead says the self sacrifice will result in Rome being Eternal (7.5). The date of book 7’s composition is debatable.

Update 10/12/15: I want to think more about how Gowing’s argument may fit into all this:

Gowing, Alain M. – Rome and the ruin of memory. Mouseion (Canada) 2008 8 (3) : 451-467 ill. [rés. en franç.]. • The importance attached to buildings is reflected in Roman culture generally, but nowhere better documented than in the Augustan program of restoration. A significant portion of that program existed to preserve the legacy and memory of Rome as manifested in buildings. Yet Romans were aware that no building could last forever ; the impermanence of buildings, especially in comparison with the immortality conferred by literary endeavours, is a standard trope in Latin literature. The eternity to which the phrase « urbs aeterna » – first attested in the poetry of Tibullus and Ovid – refers does not reside in buildings, but in the timeless landscape Camillus remembers and describes in his speech in Livy 5, 54, 2-3. [Abstract and Citation from L’Année Philologique]

—

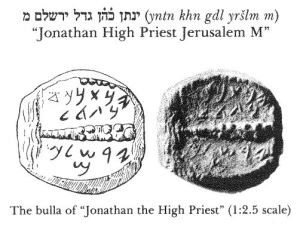

Specimen that sold in 1910: